Seeing like an Asset Manager with Brett Christophers

Last week, we listened to a brilliant conversation between Brett Christophers and Adam Tooze, moderated by Kate Aronoff at the New School in New york. Dissent Magazine has posted the audio on YouTube, and we recommend it enthusiastically. If you’ve ever wanted a Braudel and Marx take on Contracts-For-Difference, then this chat is your jam.

Brett Christophers is an absolute unit. Four blockbuster books in six years analyzing the blood and guts of global capitalism with a critical economic geography lens.

The New Enclosure (2018); Rentier Capitalism (2020); Our Life in Their Portfolios (2023); The Price is Wrong (2024).

We first came across Christophers's work on rentier capitalism via the political economist Mark Blyth. In The New Enclosure, Christophers studied land ownership in his homeland, the UK, analyzing the question: “Why has productivity growth flatlined and inequality soared?”. He found that all sectors of the economy have been transformed by capital into a “toll-booth” economy where capitalists do pure rent-collection across economic sectors.

In Rentier Capitalism and Our Life in Their Portfolios, he perched himself atop the material produced by global asset managers like BlackRock, asking just how financial capitalism has reorganized entire nations and our lives. Asset managers like BlackRock now run the roads we drive on; the pipes that supply our drinking water; the farmland that provides our food; our electricity and heat.

This summer we read Christophers’s latest book for our Polycrisis Summer book club and were impressed by how crisply it analyzed complicated electricity markets globally: in the US, China, UK, EU, and in the Global South – India, Vietnam, Nigeria, Senegal. In The Price is Wrong, he charts the profitability of different electricity markets and, crucially, the difference between the incentives for generators, project developers, and financiers, as generation-distribution-transmission were forcibly “unbundled” over the last three decades of neoliberalism. This was done globally, under IMF and World Bank diktat in poorer countries, but also inside China.

Tooze praised Christophers's forensic method: "It's a little bit like reading the account of a left-wing Martian anthropologist of how global energy systems work".

The FT’s Martin Wolf put Christophers’s thesis in a nugget: “while it is possible to prevent businesses from doing profitable things, it is impossible to make them do things they consider insufficiently profitable”. Seeing just how all the actors in Christophers's chain are not aligned at all prompted Tooze to ask the author a bigger question: “How does investment in capitalism take place at all?”

He answered: "So much [of investment] in capitalism comes down to reliable and defensible sources of monopoly or oligopoly power"; what Warren Buffet calls "moats". The problem with renewables is “the unbelievably competitive selling of an undifferentiated commodity (electricity) into an electricity market”. The observation that agents of capitalism hate competition shouldn’t be a surprise (Kate’s Economics 101 tutor pointed this out) – yet it is.

Investors demand the higher profits that renewables (with their lack of barriers to entry) can’t provide. But, how can higher profits be created? Private capital deterring entry and cheating more stable oligopolies? State’s stepping in to make publicly-owned enterprises that buy out and reorganize the sector back into distribution-generation-transmission behemoths? Christophers remains skeptical of both.

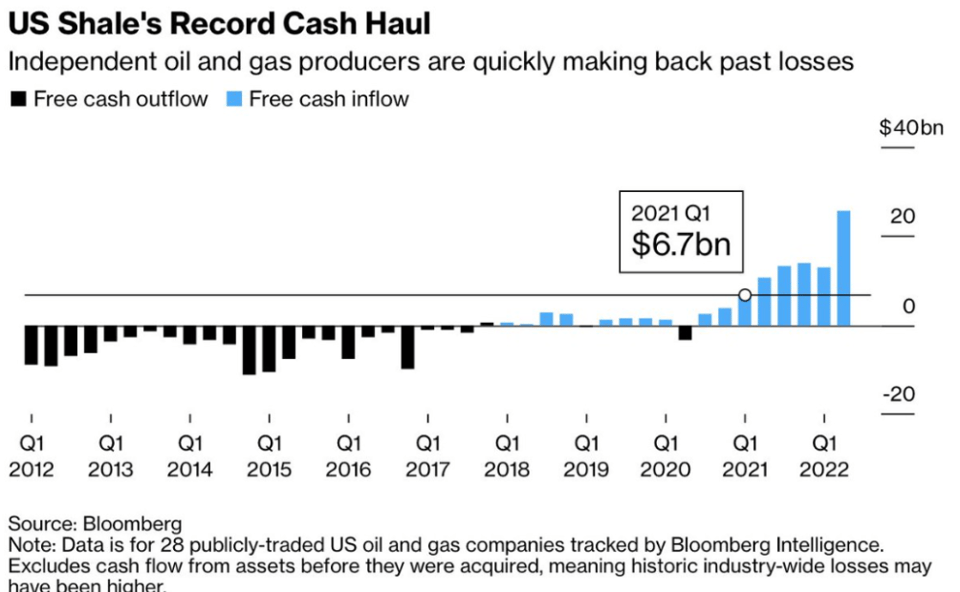

Aronoff and Tooze queried Christophers further: If profit-maximizing is what uber rational risk-averse capitalists do, then what explains their investment in fossil fuels where the US investors famously burned their cash for over a decade of the fracking boom? Where exactly is animal spirits and buccaneering romanticism in Christophers’ story?

When Aronoff and Tooze pressed Christophers on the geopolitical endgame of oil (Tooze has written about the Semienuik et al. paper in Nature) and on the lacunae of the political economy of green industrial policy in his book, Christophers demurred. Befitting a scholar, Christophers refused to pontificate on matters that he hasn’t deeply studied.

We won’t leave you hanging in our Polycrisis project! Last week Tooze published a capstone 6,102-word essay in LRB on Bidenomics that has geopolitics and nuclear crisis standoffs aplenty. Its thesis in a nugget: “Globalization was an American project, from which American businesses profited handsomely, until technological and industrial developments threatened to undermine US state power…. At that point, the American state changed the rules, joining the revisionists.”

Pair Tooze with Aronoff’s geopolitics essay on how US sanctions fuel terrible climate policy by the countries on the receiving end, and Elrod's PW essay showing exactly how the feminist and ecological promise of Build Back Better crashed into corporate power and the US Senate, and was transformed into the national-security great power politics program.

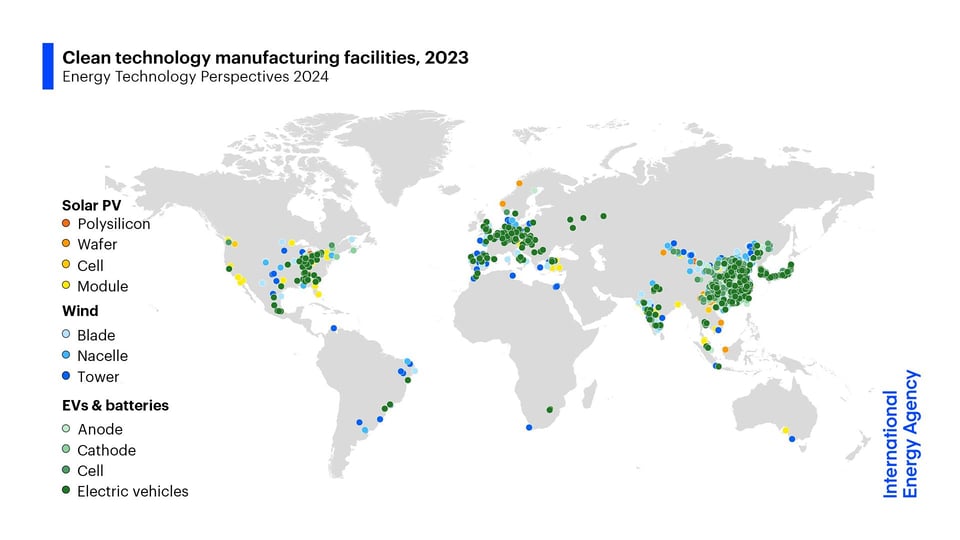

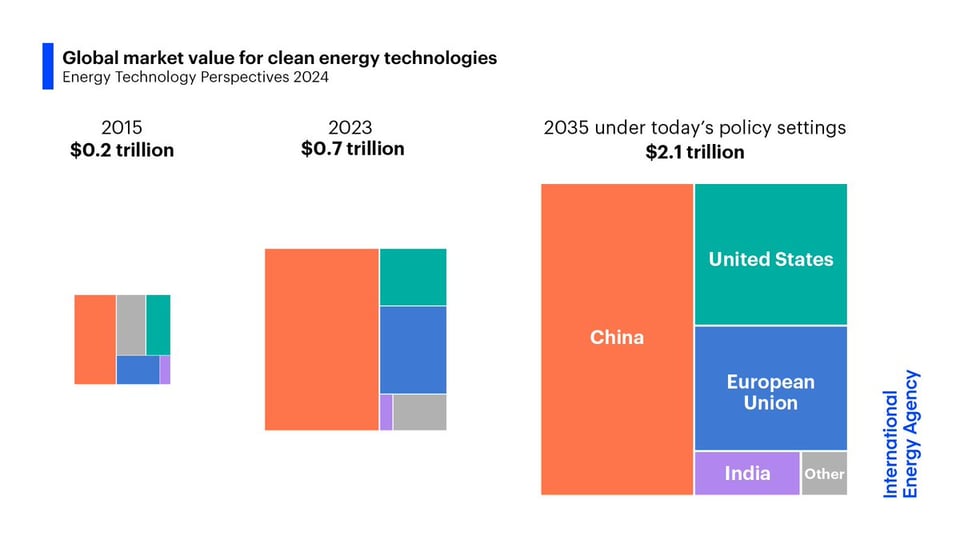

As for green industrial policy, the IEA’s big “energy bible” – the Energy Technology Perspectives 2024 report – came out this week, and is fantastic. The IEA is the global observatory of data collected from firms and national governments, and this is usually the first report that bureaucrats and companies reach for when undertaking any investment project; so we expect this report to be used everywhere.

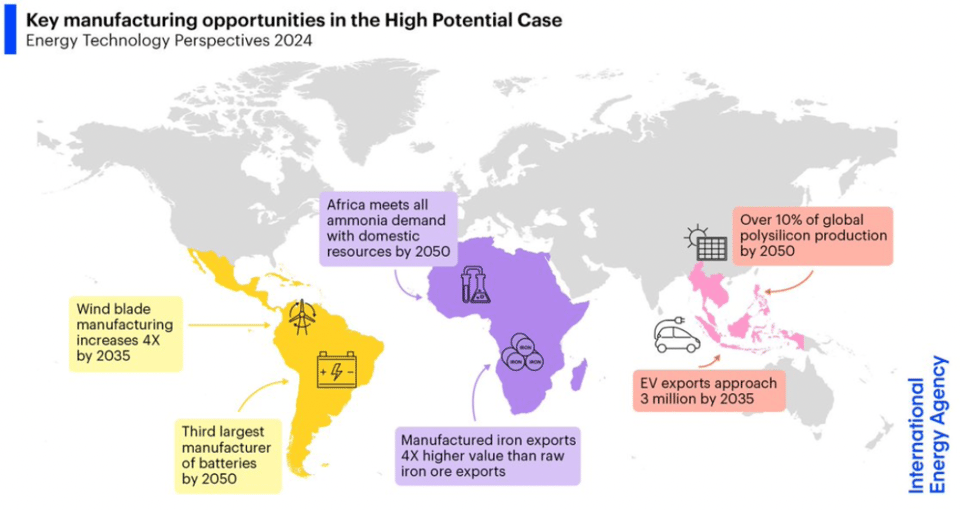

The somewhat neoliberal IEA has decided to stop fighting with countries about whether they should do industrial policy and has instead created a detailed global model to help them with planning – identifying sectors where they can develop some comparative advantage given existing knowhow and resources (wind in Latin America, EVs in North Africa, solar in Southeast Asia, etc.). In its model, clean sectors will be tripling in investment and export value by 2035 to over $2 trillion. That’s a lot of green pie to fight over. And as the Polycrisis has been arguing for a while now, developing countries do not want to turn into peasants of the new re-concentrated green world order in which the existing green winners – China, the US, and EU – dominate.

Seeing like an Asset Manager is important and Christophers is our surest guide. But capitalism is not going to transform the production and provisioning systems of the world fast enough given climate crisis with just a balance sheet view. Why don't economists and asset managers want to know anything about production? Its machines, processes and knowhow. Why are they satifsied with pinging sonar off the substance of the world? If there is ever a Christophers style dissection of industrial policy, this IEA ETP report would be its raw material.

STUFF WE ARE READING

Anastasia Nesvetailova and Herman Mark Schwartz, drawing on the newly released UN Trade and Development Report, ask: Can the Global South Prosper While the Neoliberal Order Is on Edge?

“While globalization itself may not be in retreat, three ongoing geo-economic and geopolitical shifts are transforming the long-term conditions for development and growth. First, fundamentally protectionist and interventionist policies are replacing the trade liberalization measures typical of the decades after 1990. Second, a host of conflicts has disrupted a relatively stable global security regime. Third, new technologies associated with the green transition, AI, precision bioengineering, digitalization and financial innovation have the potential to fundamentally transform the global division of labour. These three shifts inflect globalization away from a growth promoting process in the global South towards a growth inhibiting process.”

Also, two excellent stories in Bloomberg in the past month:

Florida vs Jamaica: How ‘Hurricane Insurance’ Pays Out or Fails (paywall) – Rich countries get insurance based on damage assessment; poor countries get "parametric triggers".

What Really Happens on the Ground When the US Slaps Tariffs on China – How tariffs actually work: the “cat-and-mouse game” of getting around China tariffs meets a tit-for-tat battle between two small-town truck chassis manufacturers in the US.

Add a comment: