Power and Powerlessness

Welcome to our 18th edition, coming after a bit of a gap due to travel, illness, and the hecticness of Climate Week/UNGA events. Tim spoke at a few panels, including the Project Syndicate live event on Latin America in the energy transition on Sunday. We also met up with old friends, new collaborators – and, for the second time ever, each other!

Our newsletter today is sidestepping Israel’s invasion of Lebanon (quietly backed by the US) and frenetic hour-by-hour diplomacy to avoid an enormous middle east war. Instead we examine three oil exporting countries grappling with energy transition: Angola, Colombia, and the US; which has been hit by a devastating climate-charged hurricane that reveals its need for a domestic “Marshall Plan”. Also, a few climate week highlights on Ecuador’s buen vivir and the horror of discount rates.

Biden meets strategic non-alignment in Africa

Angola is about to get a lot of western attention as Joe Biden visits the country later this month – his only trip to Africa as president.

Angola is the second-biggest oil exporter in Africa, and the continent’s biggest debtor to China. Its government is also no slouch at practising non-alignment. Angola recently quit Opec+ in disagreement over quota allocations; in the wake of Covid it has struck multiple agreements to reprofile and delay its official Chinese loan repayments; and the US and Europe have pledged to support building a rail corridor from DRC to the Angolan port of Lobito – a huge project that is fraught with challenges.

It is also the destination for 62,000 home solar panel kits from Germany. (It’s not clear if this deal received international climate finance; however a similar arrangement in Senegal was financed by KfW). Angola’s finance minister, Vera Daves de Sousa, told Reuters last month that the country would buy clean tech from whichever country provided them the finance to do so.

"This is a tough discussion, because in our case, this comes together with the financing solution," Daves de Sousa said.

"If Angola's fiscal revenues were strong enough to allow us to choose based on the criteria of quality and price, we would have a totally different discussion."

The country gets somewhat less attention in international media than, say, Colombia, whose president Petro has been vocal about wanting to quit the oil industry. Colombia has joined a dozen other countries in signing the fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty, despite oil and coal accounting for 10% of its GDP. Colombia is sharing some details of its new energy transition plan, for which it will seek about $10 billion in international finance. Nature and tourism feature in its vision of alternative sectors; later this month when the country hosts COP16, (the Convention on Biodiversity, rather than climate).

The concept is likened to the “JET-Ps” coal transition plans in South Africa, Indonesia and elsewhere. These have not been a resounding success so far and from what we’ve seen, Colombia is developing something more like a “country platform” in that it that goes well beyond the energy sector, due to Colombia’s reliance on fossil fuel export earnings. Like Angola’s Daves de Sousa, Environment minister Susana Muhamad is not mincing words about the role of wealthier countries. She told Mythili Rao and Akshat Rathi:

Everybody says, ‘Oh Colombia is so ambitious. Oh Colombia is leading this and leading that.’ Yeah, I mean we have done everything that is on the table, and it’s still not enough. So we need to demonstrate collectively that this is possible. Otherwise we are just selling smoke at every COP, really.

Power and powerlessness in the US

The US is experiencing an intense Polycrisis moment:

1. Massive insurance catastrophe as Hurricane Helene smashed into upland parts of North Carolina that don’t usually experience hurricanes, and were indeed described as a “haven” from climate change (although some analysis pointed out the opposite was likely). As Kate Aronoff put it in the Nation: "Climate change isn’t a discrete issue so much as the foundation on which all politics happens. All policy, in other words—from housing to trade and financial regulation—is climate policy."

2. Democratic backsliding and unprecedented flooding combine in potentially large disenfranchisement for North Carolinians. As the storm broke roads and brought the postal service down, 190,000 absentee ballots may not make it into the US elections.

- 3. The Appalachian is one of the most deprived parts of the US. Rural America lacks basic services of water, sewage lines, housing. A 2017 UN study found that 5.3 million Americans live in “Third World conditions of absolute poverty.” When it comes to emergencies, poverty and Climate disasters combine viciously. Governments usually want to triage their limited resources to help communities most in need during a disaster. The standard recommendation is self-help so as to avoid overwhelming emergency services. However, if people are poor, it is hard for them to have pre-purchased 3 days worth of food and electricity and fuel buffers . For all the talk of global green Marshall Plans from US policymakers, this kind of socioeconomic breakdown points to the enormous needs of a developmentalist green Marshall Plan for Americans.

US solar power debacle and dam failures

Bloomberg ran a couple of excellent, deeply-reported stories this week. First, “How the US Lost the Solar Power Race to China” analyses the history of the polysilicon used for solar panels, and particularly the role of subsidies in the growth of solar manufacturing in Leshan, near Guangzhou, and the disappearance of the same industry from Hemlock, Michigan – which dominated the polysilicon market only 15 years ago.

Is Tongwei’s cheap electricity from a state-owned utility a form of government subsidy? What about Hemlock’s tax credits protecting it from high power prices? Chinese businesses can often get cheap land in industrial parks, something that’s often considered a subsidy. But does zoning US land for industrial usage count as a subsidy too? Most countries have tax credits for research and development and compete to lower their corporate tax rates to encourage investment. The factor that determines whether such initiatives are considered statist industrial policy (bad), or building a business-friendly environment (good), is usually whether they’re being done by a foreign government, or our own.

The TL;DR is the US in particular (and to a lesser extent, the EU) dropped the ball on solar due to corporate skittishness, higher energy costs, and lack of policy certainty. But a real inflection point was an opportunistic and ill-considered trade war between the US and China on solar panels from 2013. One positive element of the story is that the EU, by not digging in on dumping accusations against Chinese rivals, at least managed to continue exporting its polysilicon to China. It illustrates why German car manufacturers are aghast at the big new EU tariffs on Chinese EVs.

Meanwhile US dams are mostly far too old and their flood-related resilience is not informed by climate change in most states – the “probable maximum precipitation” or PMP level was developed in the 1940s. It is an example of the many thresholds that underpin much of our built environment, and are becoming vulnerabilities as the climate heats up. Funding is of course the other key issue; the story finishes with a quote from precipitation expert Bill McCormick: “Not every dam is a hydroelectric dam. So not every dam generates revenue by producing power.”

Europe, climate, and democracy

One Climate Week event we both attended was a symposium at NYU on Europe and social and democratic responses to the climate crisis, which included friends of The Polycrisis such as Isabel Estevez, Pierre Charbonnier, and Alyssa Battistoni.

We were blown away by the talk by former Ecuadorian government advisor Andrés Arauz, who laid out the Correa government’s pursuit of “buen vivir” rather than simply “development”; how international rules and laws prevented the realisation of those goals; and how the UN’s “System of Environmental Economic Accounting” offers an alternative to the prevailing metrics of sovereign success.

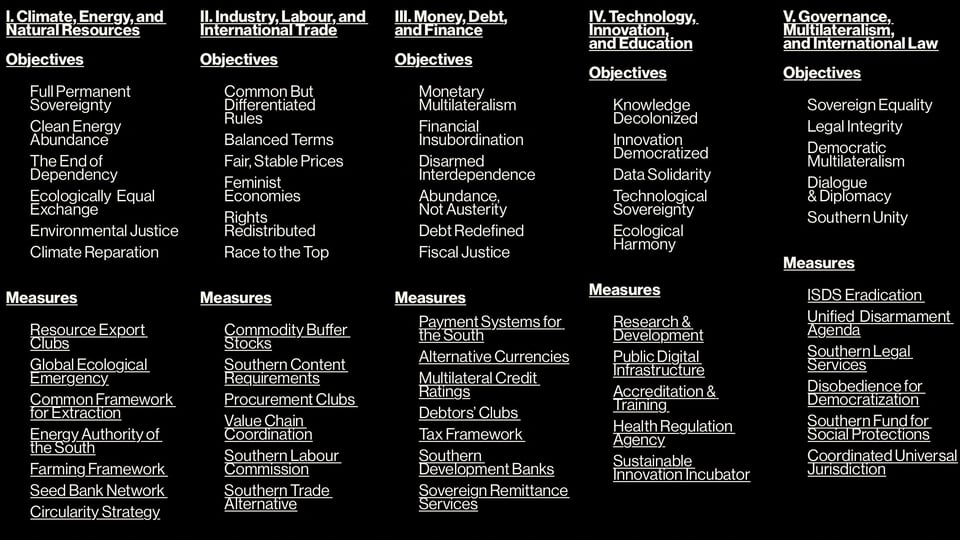

He described his proposal of a producer club of mineral-exporting countries; collaborating not just on price and volume targets as OPEC+ does, but also on worker conditions and environmental care. Arauz’s proposal was among those released during Climate Week in Progressive International’s striking Program of Action on the Construction of a New International Economic Order: a handbook for an insurgent South in the 21st century.

Another great provocation came from economic sociologist Liliana Doganova on the origins of discount rates and their pernicious, selective application in investor-state disputes and climate policy cost-benefit analysis. Her essay in The Break Down describes it beautifully.

Draghi misses the point: Do listen to Isabella Weber on Lots More about the Draghi report; she points out that while it embraces industry policy at a sectoral level, it stops short of acknowledging the supportive macro financial framework required to enable it. Schwarze null and the austere ‘Swabian housewife’ feature.

That is all for this week. Please forward this to anyone who might be interested!

Add a comment: