Minerals stockpiles, 'geoeconomics' and debt

Hello readers! This week we look at stockpiling minerals as a security and transition strategy; “geoeconomics” [scare quotes: correct]; and how to evaluate hegemonic power. Plus, the new pope and debt in this Jubilee year.

A lot of this edition builds on work and links from our readers and contributors in the Discord. Please email us if there’s anything you’d like to see (links below). This week we’ll be working on our next Phenomenal World essay, about insurance, but plan to send out a short Dispatch.

Stockpiles

China in early April restricted exports of seven rare earth elements to the US; removing them was “high on the US wish list” for the talks with China that took place on the weekend (at pixel time, though, we don’t know what exactly was achieved).

The US is, of course, highly dependent on China for rare earths and many other critical minerals, and it’s not alone in worrying about the vulnerability that creates. There are different ways around this; stockpiling is one that’s particularly disliked by free market adherents, but currently having a bit of a renaissance.

The Biden administration had made the Strategic Petroleum Reserve more strategic by restocking supplies at a publicised price window. That created a degree of price stability for crude oil, as well as ensuring emergency supplies — its longstanding purpose. Substances like lithium and rare earths used in batteries are mined in small volumes compared to feedstock commodities, and the resulting price volatility deters companies and investors from producing more of the stuff. Employ America, who devised the SPR forward contract idea, had proposed that it be used for critical minerals, too.

It’s not clear how or whether that will happen under the Trump administration, Alex Turnbull (who worked with Employ America on a lithium stockpiling proposal) is optimistic that Australia and Canada will develop critical minerals reserves, even while it’s not clear whether the Trump White House will continue with the lithium plans. Australia is looking very likely to create reserves of several (unspecified) critical minerals, as its newly re-elected Labor Party promised in the election campaign to invest $1.2bn in offtake agreements and stockpiling.

The platform promise mentions the facility will generate cashflow, although it’s not clear if it's that’s in aid of the kind of price volatility goals set out by Employ America. Mohan Yellishetty, a professor at Australia’s Monash University, noted that:

Australia lists 31 critical minerals while Japan lists 35, the US lists 50 and the European Union 34. Australia’s list is unique in that it reflects global demand, not domestic dependency.

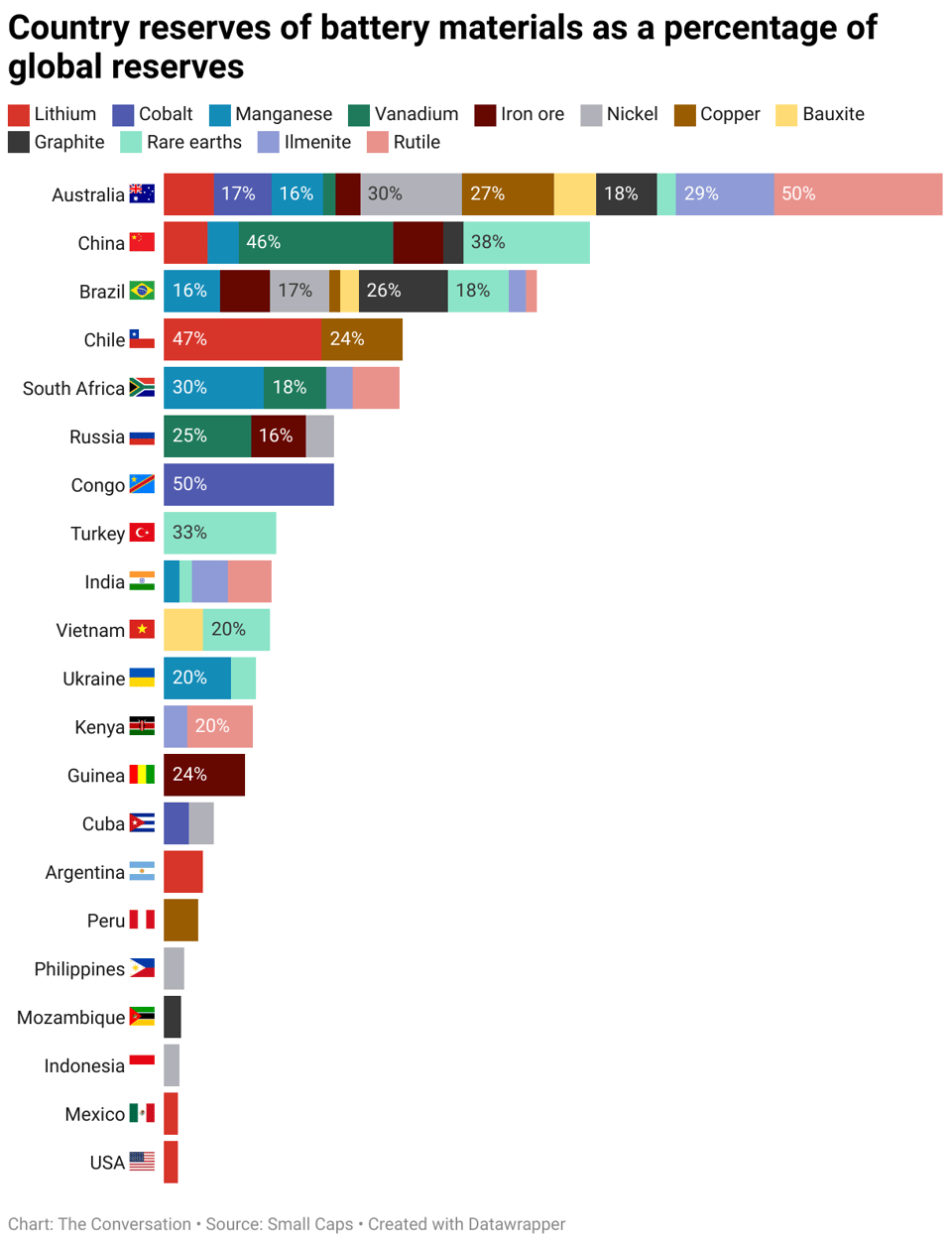

Australia, of course, is a big exporter and has a lot of reserves of many critical minerals minerals:

Looking through the international initiatives that Australian researchers are already engaged with suggests there’s a lot of collaboration already taking place between Australia and India, and Japan and, to a lesser extent, South Korea.

Canada hasn’t set out a stockpile plan but it has pledged to support the establishment of new mines, and prime minister, Mark Carney, told the BBC that Canada “could supply the US with” critical minerals, and has pledged more conventional support measures such as a “first and last mile fund” for supply chain connections, and to de-risk mining investments.

Does any of this bode well for Global South countries with reserves of these minerals, that wish to use them for development as well as foreign export earnings?

That might be best answered in Europe, which unlike Australia and Canada doesn’t knowingly have a great deal of mineral resources – or at least, is unlikely to want to mine them. Jewellord T. Nem Singh pointed out that Europe’s goals to invest in minerals processing might “contravene efforts by mineral producers to increase value-added activities as they attempt to incorporate their exports into the supply chain of clean energy technologies”.

Alex, meanwhile, is pessimistic about “anti-action bureaucratic bias of the EU” preventing the bloc from any meaningful progress. The European Commission in December formally approved a Memorandum of Understanding on critical minerals with Democratic Republic of Congo — more than a year after the MoU was signed.

Don’t get too carried away with critical minerals extraction, however: a decent amount of resources can be sourced by improving recycling (which the EU, to its credit, is trying to do) and which the IEA suggests could help developing countries with electric mobility uptake. Another way to ensure adequate and stable supplies is reducing demand by not making quite so many enormous cars.

Geoeconomic power, modelled

Christopher Clayton, Matteo Maggiori, and Jesse Schreger have a working paper called “Putting the economics back in geoeconomics”. They define geoeconomic power thus:

Power comes from the fact that the targeted entity is willing to take this privately costly action to either avoid a punishment or earn a reward. If the entity is worse off taking the action, it will not do so. This participation constraint is the key to geoeconomic power projection. Power, therefore, is rooted in the ability to shape the target’s incentives. [...] Hegemonic countries, however, often seek to influence foreign entities over which they have no direct control. They do so either by threatening negative consequences if the target does not undertake the desired actions, thus lowering the outside option of the participation constraint; or by promising positive benefits if the target does undertake the desired actions, thus increasing the inside option of the participation constraint.

It then sets out ways that the kind of economic statecraft accoutrements of modern hegemony can be modelled in a macroeconomist-friendly way.

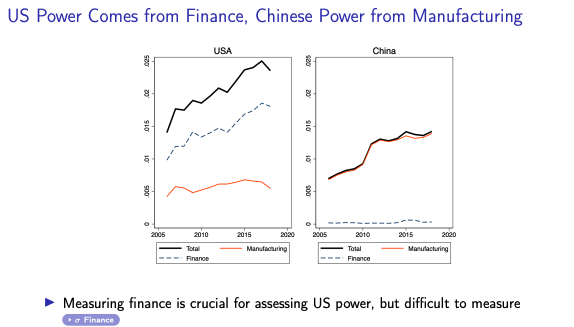

An earlier presentation on this work by the authors included the following chart:

One of our readers on the Polycrisis Discord pointed out that this is just a reworking by economists of work done in other academic fields, like comparative political economy.

The authors are probably not disputing this, Two of them, Maggiori and Schreger, were interviewed on the “Macro Musings” podcast in late 2023, and they noted that their work built on that of political scientists – They also refer to Dan Drezner’s “economic statecraft syllabus” reading list as a key resource.

The paper shows that their modelling affirms what political scientists and political economists had been saying already: that hegemons can benefit from restrictive rules simply because they remove motivation for other countries to reduce their dependence on the hegemon. So it is not a benign hegemony, but a self-interested hegemony realised through a benign framework.

Our theory highlights that the hegemon can benefit from a rules-based international order – even rules that only apply to itself – because those rules provide commitment power that limit motives of other countries to engage in economic security policies that reduce their dependency on the hegemon. This echoes a view from political science that international organizations are the expression of Great Powers and serve to improve the welfare of these dominant countries (Baldwin (1985)). Indeed, the topic of a US-centric “liberal hegemony” has attracted an intense debate (Ikenberry (2001); Mearsheimer (1994, 2018); Walt (2018)). It also echoes the analysis of Bagwell and Staiger (2004) of the incentives of large countries to sponsor trade agreements even if they limit their ability to manipulate the terms of trade.

They focus particularly on financial tools as a means of effecting this sort of power; and their definition of geoeconomic power is striking in its similarity to the sovereign debt regime – or the non-existence of such a regime; the lack of which is extremely detrimental to debtor countries. It doesn’t seem to have been used yet to explore how either the problematic legal regimes in the US and UK, or the threat of punishment by eurodollar markets, enforced by credit ratings agencies, might constitute another form of geoeconomic power.

New pope, and debt

A lot of the coverage of the new pope focuses on his being a US citizen and a broadly progressive figure — and engaged with climate change. We’re also interested in how focused he might be on sovereign debt. This is a Jubilee year for the Catholic Church; something that has taken place every 25 years for centuries and is meant, among other things, to be a period of debt forgiveness.

The year 2000 Jubilee was the focus of a multi-year campaign for debt relief and Debt Justice UK (formerly Jubilee Debt Campaign) is hoping that some of the unfinished work can be addressed this time. Jubilee USA Network welcomed the new pope, Leo XIV, pointing out that his most recent namesake, Leo, was a supporter of workers and the poor.

Another rare event in debt is the fourth Financing for Development (FfD4) conference that takes place in Seville next month; the first one since Addis Ababa in 2015. Campaigners are pushing for a UN Sovereign Debt Convention; thinktank IDDRI also expects a lot on taxation – both domestic and international.

LINKS

Jeremy Wallace defends the Naomi Klein & Astra Taylor “end times fascism” essay against Adam Tooze’s criticisms.

Last week, we wrote about Helene Rey’s talk at a Bruegel-DNB conference on Europe’s response to the US abandoning key aspects of its currency hegemon role. A few days later she was in the FT explaining how a more international euro doesn’t actually require a current account deficit, and “could allow the Eurozone to capture a portion of the exorbitant privilege and convenience yield, thereby lowering the cost of capital for European firms and governments.”

If you’ve wondered about crypto money in US politics, so did we. (The Nation)

THE END

That’s it for this week!

Add a comment: