Magic Pony, Groundhog Day

Welcome to our 20th Dispatch. It’s quite a time. The IMF/World Bank annual meetings in DC (Tim was there, where he spoke on a ‘making the world order safe for industrial policy’ panel organized by Common Wealth), and the BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia. The US election a couple of weeks away. Then a week later, COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan.

The COP is about finance and updating national commitments before the February 2025 deadline. The US election is about, well, potentially everything.

We start with global finance, where there are tentative signs of a consensus shift away from belief in private capital as a key way to support decarbonization and development; then look at Brazil’s GFANZ-endorsed country platform; the G20 TF-Clima export group’s report calling for green industrial strategy; and Sullivan’s speech suggesting attempts to address Congressional blocks to financial reforms.

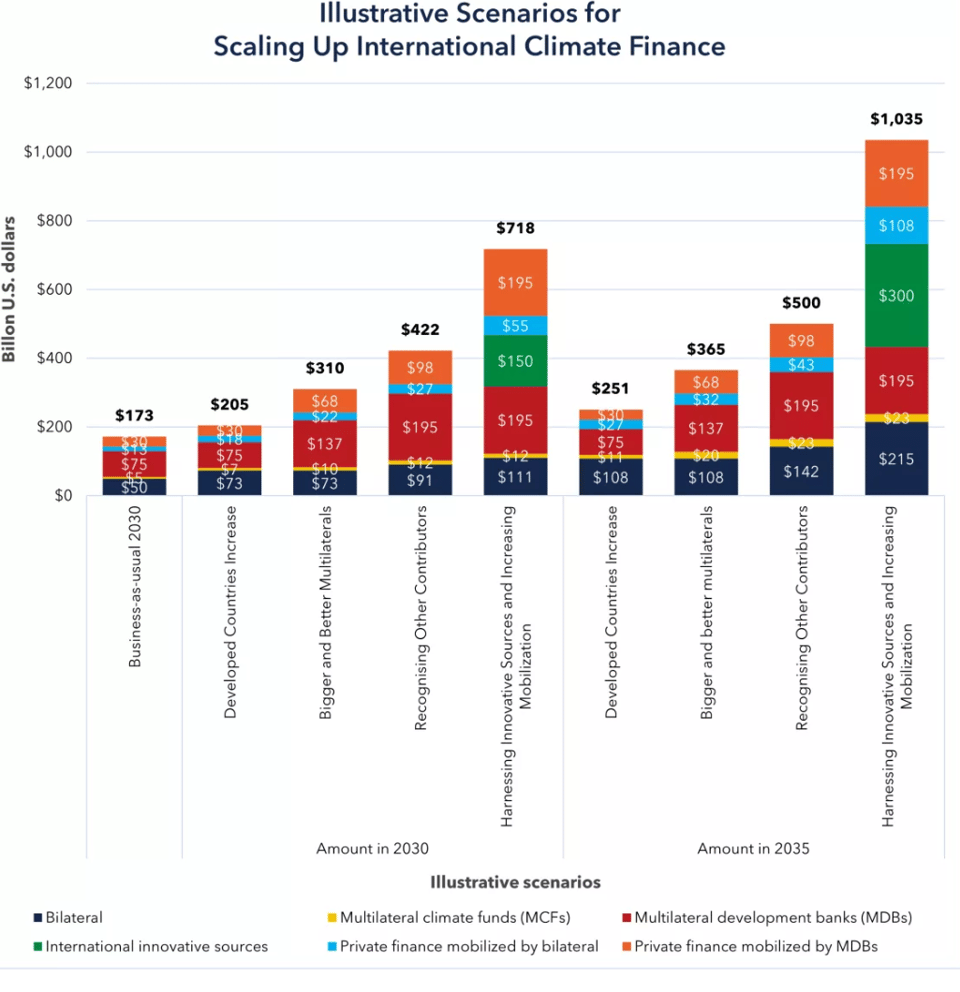

The anguished question of where the money could come from is still unanswered. Researchers from four thinktanks and NGOs attempted to answer it quantitatively:

What are the green “innovative sources of finance” that are doing a lot of the lifting in the scenarios that are in the ballpark of meeting the required amounts? The authors write:

Potential sources include IMF issuances and rechannelling of Special Drawing Rights, the share of proceeds going to the Adaptation Fund from the Paris Agreement’s Article 6 Crediting Mechanism, and pollution taxes on international shipping and aviation. Estimates of revenue potential from different levies vary widely, from less than ten billion to over $100 billion per year so we kept range of values wide to allow for a variety of perspectives about which mechanisms might be deployed and how much revenues might be raised. Funding from innovative sources is likely to be focused on activities such as adaptation and loss and damage that require mainly grant financing so are difficult to fund from other sources. As a result, we do not assume they will mobilize any private finance, though in reality they may help do.

It’s notable that private finance is excluded from the “innovative” category, as this label is often used as shorthand for precisely that. SDRs and (especially) aviation levies are incredibly ambitious, but at this stage they’re looking more plausible — if only because they’re less tested — than “magic pony” aspirations about finance from private sources, which pop up again and again, without reference to everything that’s come before, like some kind of Groundhog Day.

There is enough experience to suggest that the various regulatory, compliance, architectural and cultural barriers mean private finance has little chance of meeting the gap of finance for development, climate mitigation and adaptation in the time required. Larry Summers – again! – was a critic:

Asked about private capital mobilization’s ability to fill financing gaps. Larry Summers—*Larry Summers*—said it’s “piffle” from people who want to sound ambitious but don’t have public resources or private sector chasing subsidies.

— Tim Hirschel-Burns (@TimH_B) October 23, 2024

“It’s like me saying I’ll run a 4-minute mile” pic.twitter.com/vgJ9hjy1FW

This comes after Alan Beattie’s scathing “magic pony” newsletter in the Financial Times, excoriating empty announcements and several decades’ worth of World Bank leaders for trotting out the story that IFIs will be able to mobilize capital with enough financial engineering.

Brazil’s climate country platform

But opportunities to engage with private finance remain compelling for states. A big set piece this week was Brazil announcing its country platform, the Climate and Ecological Transformation Investment Plan, or BIP at a side event to the G20 finance ministers’ meeting.

The core proposition is that Brazil’s development bank, BNDES, will identify projects that align with the country’s Ecological Transformation Plan, its Nova Industria plan and its updated Nationally Determined Contribution; the climate target plan submitted to the UNFCCC last year. The idea is that this means investors will… invest in them? The six pilot projects announced this week are intended to “mobilize” a big number: $10.8 billion once final investment decisions are made.

The BIP is co-branded with GFANZ, the private finance alliance which had its big debut at COP26 in Glasgow three years ago, when Mark Carney insisted that some 130 trillion dollars were waiting to finance the transition in developing countries. Other GFANZ-endorsed partnerships don’t appear to have yielded much if any private investment — the JET-Ps are a standout example of this. The deep government involvement and the identification of specific projects makes this initiative, potentially, somewhat different; if only for evaluating progress.

Brazil is a big upper-middle income country with better prospects of benefiting from such initiatives than low-income countries (which only accounted for a tenth of mobilized private capital in 2022). Lula and his finance minister, Fernando Haddad, met with the three big credit ratings agencies in New York last month. Each agency has the country one or two notches below investment grade, and Moody’s upgraded its rating recently. A hope in policy circles is that, through its role as G20 and then COP host and Lula’s regional leadership and South-South cooperation, Brazil can lift prospects for other countries.

For many of those countries the options are very limited. Lara Mehling’s essay in Phenomenal World this week analyses how the IMF’s incorporation of climate into its programs is really greenwashing structural adjustment — imposing the same austerity and deregulation, liberalisation and privatisation measures that are almost impossible to undo — and preclude the possibility of green industrial policy.

Hawkish finance

US national security advisor Jake Sullivan gave a speech at the Brookings Institution, a follow-up to his “small yard, high fence” speech that we analysed 18 months ago. Speaking again to both foreign and domestic audiences, Sullivan used the phrase “positive sum” six times to argue against the entrenched DC view that factories overseas come at the expense of American workers. Sullivan offered an alternative view: investment in climate, manufacturing, and technology is collaborative and requires participation by all countries.

“The challenges we face are not uniquely our own and nor can we solve them alone. We want and need our partners to join us. And given the demand signal we hear back from them, we think that in the next decade, American leadership will be measured by our ability to help our partners pull off similar approaches and build alignment and complementarity across our policies and our investments.”

Sullivan cited beneficial foreign investment and jobs that are supported by US public investments, and listed similar initiatives from US partners: Japan’s green transformation policy, India’s production-linked incentives, Canada’s clean energy tax credit, the European Union’s Green Deal.

As for the Global South, like his previous speech, he listed the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Governance, G7’s answer to China’s Belt and Road. But unlike his previous speech, he appealed for Congressional support on ways to provide more financial support for Global South countries. He stressed that the amounts only need be tiny:

“For example, our administration requested $750 million — million — from Congress to boost the World Bank’s lending capacity by over $36 billion, which, if matched by our partners, could generate over $100 billion in new resources. This would allow the World Bank to deploy $200 for every $1 the taxpayers provide.

Sullivan also made clearer efforts to link his foreign policy agenda to the financing gaps in the global south:

“We need to focus on the big picture. Holding back small sums of money has the effect of pulling back large sums from the developing world — which also, by the way, effectively cedes the field to other countries like the PRC. There are low-cost, commonsense solutions on the table, steps that should not be the ceiling of our ambitions, but the floor. And we need Congress to provide us the authorities and the seed funding to take those steps now.”

G20 and industrial policy

Also launched this week was a report by a Group of Experts assembled to advise TF-Clima, Brazil’s G20 Climate Taskforce. The report states that green industrial strategy and green finance are the keys to achieving climate goals.

The group’s members’ have very divergent views on the role of the state and of finance but, even so, the rebuke to private capital was stark:

BRICS, the panel

To end with, here is Tim’s panel:

We didn’t write about the BRICS summit in the end; but Russia’s efforts to advance de-dollarization didn’t seem to gain much traction, likely for structural and political reasons that are similar to last year.

We will be back next week. You can email us here: Kate and Tim.

Add a comment: