It's about oil, no it isn't, yes it is

Also, sovereign creditors

Happy new year. We are still semi-on holidays but the Venezuela incident has a lot of Polycrisis-ish elements, plus of course some more novel ones. Kate found the oil angle — and especially the discourse around it — most interesting; Tim found the trade-offs and assets/liabilities calculus most interesting.

Meanwhile over on the discord some of us were nerding out about Melinda Cooper, whose epic interview on The Dig about her book “Counterrevolution” sets out a gripping picture of connections between fiscal and monetary policy, neoliberal politics, provincial and federal taxation, and US morality politics, from the 1970s to almost today. We are definitely planning a book club on this!

So, on to Venezuela. Here is our oil take which we trust will maintain salience for at least a few more hours:

The US administration says it is about oil. They keep saying it: the latest statement is specifically about 50mn barrels of oil, the proceeds of which will be split between the US and the “people of Venezuela”. (No time frames. That would be about the amount of crude that Venezuela exports in a couple of months, prior to the blockades of late 2025.)

The narrative that “this is all about oil” has several huge flaws. Karthik Sankaran, Adam Tooze and numerous oil people have explained that Venezuela’s oil reserves are more tenuous rather than the “world’s biggest” label would suggest. Firstly, Venezuelan crude is extremely dense and sulphurous, meaning it is expensive and energetically costly to refine; and only some refineries are equipped to do so. Furthermore, Venezuela’s ailing oil infrastructure will be expensive to maintain and improve. Finally, political instability is anathema to the oil majors.

Despite this, there are a few ways the oil-driven narrative makes some sense (although, even taken together, they don’t necessarily add up to a compelling rationale for capturing the head of a sovereign state):

- It projects the idea of US dominance over a big swathe of the world’s fossil fuel resources. This needs no explanation: it is a clearly and repeatedly stated objective of the US administration.

- It projects the idea that fossil fuels are dominant in geopolitics. This one is probably even more anciliary than the others, but it ties in with something we’ve been saying for some time that maintaining a sense that fossil fuel demand is growing appears to be an objective shared among most petrostates and the commercial oil industry, who for the last two or three years have been vigorously trying to drown out and deny the signs of oil demand entering terminal decline and a global glut of LNG.

- It satisfies Trump’s penchant for acquiring control of other countries’ extractive resources. No elaboration required.

- It sends specifically threatening signals to some countries. For example: China, the main buyer of Venezuelan crude (although this seems unlikely to bother China). Canada, which is the main supplier of heavy crude to the US. Russia, which would suffer from further crude oil price falls; as would most OPEC members (Venezuela itself is a member of OPEC).

- It probably helps a bunch of US oil companies; not the industry majors, who have high thresholds for risk, but the smaller and often privately-held services companies. It also probably helps activist fund managers -slash- Trump donors who recently acquired Venezuelan refining assets in the US, in US court-ordered auction.More on the US oil companies element

It might be worth unpacking that last point a bit more, as there’s enough possible beneficiaries to provide quite an array of stories:

Elliott Management has been highlighted as a likely beneficiary due to its recent US court-enforced purchase of the Venezuelan state-owned refinery company, Citgo. The fund is run by Paul Singer who happens to be a Trump donor. Shares in the the listed US oil services companies like Schlumberger and Baker Hughes all jumped early this week, by as much as 8%. The FT’s Lex column calculated that justifying this degree of share price rise requires a dogged belief in everything working out perfectly; or an absurd assumption that Venezuela will bring revenues of 5 or 6 times what those companies earn from the rest of the LatAm region. But then, they point out, markets are mostly just vibes these days anyway.

Oil dominance as a signal

As we said above, one goal of the US administration, along with most other petrostates and the oil industry, is to keep pushing ahead with assumptions that demand for oil (and gas) will continue to require more and more extraction; even in a complete absence of convincing evidence.

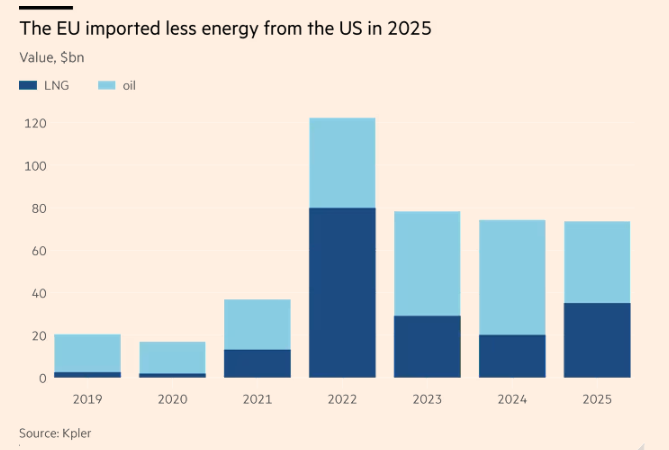

A complimentary, and more concrete, element of this goal is the White House insisting that other countries commit to buying US fossil fuel exports, or even investing in projects, in exchange for less punitive tariffs. Even though these arrangements have had enough success to sprinkle stories of MOUs and extra shipments around, they’re not that effective. For example Europe, which enthusiastically signed up to a big commitment to increase US LNG imports, actually spent less on US fossil fuel imports last year than they did in 2024:

Boccara of Kpler said that even if the EU were to replace all Russian gas with US supplies, it would still not be enough to triple the import value. “We just can’t buy into the clear rationale other than obviously [the trade deal] is a way to reduce [US] tariffs,” she added. “We just can’t see the math working out.”

Markets are expecting an oversupply and lower gas prices in the coming years, as countries including the US, Qatar and Canada plan to increase production.

The potential for a Russia-Ukraine ceasefire has also cooled market sentiment. Martin Senior of Argus said that both the EU and the US lacked sufficient import and export infrastructure, such as storage tanks and regasification systems, to significantly expand their energy trade. The EU would need to increase import capacity by more than 50 per cent, while the US would have to more than double its export capacity to commit to the trade deal, he said.

Guaranteeing western hemisphere oil hegemony

The “guaranteeing oil dominance” theory also deserves more unpacking (not least because it is a popular idea from oil commentators).

Having de facto control of the Western Hemisphere’s petroleum wealth is a geopolitical game changer. For decades, US military adventurism was constrained by the impact of any war on energy costs. Today the White House has primacy over oil-producing allies and adversaries alike — whether it’s Saudi Arabia or Iran, Nigeria or Russia.

This explanation holds a lot of water if you’re thinking geo-strategically: which countries can you punish, or threaten to punish, by ramping up supply and suppressing prices? It also, however, requires some confidence that declining demand won’t take care of that anyway; plus confidence that Venezuela’s oil sector can really be mobilized quickly enough to make this worthwhile.

And can it be mobilized?

One thing about Venezuela’s oil prospects is the sheer lack of hard numbers around costs. The reserves are big, but the calculus on extracting them is tricky.

Shreiner Parker at Rystad told the FT that it would cost around $65bn to just maintain Venezuela’s oil extraction infrastructure, and perhaps more than $100bn to expand output. (For context, Exxon will invest a total $60bn in Guyana, the world’s only big new oil play, which has a very amenable government.)

Wood Mackenzie, however, thinks it’s a little more trivial than that:

Operational improvements and some modest investment in the Orinoco Belt heavy oil region could raise Venezuela’s production back to the levels of the mid-2010s at around 2 million b/d within one to two years, given favourable conditions.

Going beyond that would require significant investment, probably focused on the Orinoco Belt. Most of the upgraders needed to process the region’s oil went offline between 2019 and 2021, and the ones that remain in service need consistent expenditure to keep running.

Wood Mackenzie estimates that the Orinoco Belt joint ventures between the national oil company PDVSA and international oil companies would need US$15 billion to US$20 billion of investment to ramp up over the next 10 years, to add another 500,000 b/d.

Some more reading:

Background about Delcy Rodriguez and her brother, from The Miami Herald.

A point from a Venezuelan person, which we found particularly poignant in light of the Gen Z protestors of 2024 - 25.

“Saying that this matter should've been solved by Venezuelans is, at best, ignorant. We've tried everything. A massive strike in 2001, huge mobilizations in 2009, 2014, 2017 & 2019 (just to name a few years), the electoral way, internal coups, you name it. Two high-ranked military officials have tried coups. They both died horrible deaths at the hands of the government.