How Deese got there

Welcome to another Polycrisis Dispatch. This is edition #15! This week the Brian Deese — former WH National Economic Council director of Bidenomics — essay in Foreign Affairs calling for a “green US Marshall Plan” has inevitably drawn a lot of attention. We’re planning a bigger analysis in the next Polycrisis newsletter around mid-late September. (If you’re not signed up, go here and do it). This week, we reflecting on pivotal moments and themes that led to this particular development.

But first, let’s deal with the concern over the “Marshall Plan” label:

Whatever its shortcomings, Deese’s proposal does attempt to reckon with new realities: China has had a Cambrian Explosion in clean tech manufacturing; China’s overseas development finance is seen in the south as more appealing and less conditional than the US; many southern countries are exasperated with the world order; and US domestic politics are in a permanent trench war. And climate change can’t be stopped without addressing all of this and more.

The list below isn’t a comprehensive or chronological. Some are events or developments; others are dawning realisations that have been a long time coming:

China’s rebooted export-led growth model focusing on clean tech manufacturing, rather than simpler manufactured goods of its initial export growth phase after being granted WTO accession in 2001. Although it was many years in planning, the speed with which cheap, appealing Chinese-made and branded EVs became popular within China and increasingly in other countries took foreign rival companies and their governments by surprise. Once a huge market for western and Japanese brands, Chinese consumers began to prefer local brands that had become fiercely competitive in the domestic fitness center-slash-market, and all of a sudden China was the biggest auto exporter. “Boardrooms in America, Europe, Korea and Japan are in a state of shock,” a car industry analyst told the FT in January. China’s PV solar cell exports have been on this path for a while; while surging volumes and declining prices of China’s steel exports is creating a protectionist outrage in numerous countries, including India, Mexico and Brazil.

The “Chinese Green Marshall Plan” idea gained ground. The idea of greening the “Belt and Road Initiative” has been more talked about than evident since the BRI began over a decade ago. China began to pull back on its lending in 2019. But a speech by Huang Yiping, Peking University Boya Distinguished Professor and Dean of PKU National School of Development, drew attention in the English language media as he proposed that a “Chinese Green Marshall Plan” would be a neat way of turning China’s alleged overcapacity into a boon for its global aspirations: if the US and Europe wanted to throw up a Great Green Wall against cheap Chinese EVs and solar panels, why not help developing countries to buy and make them instead?

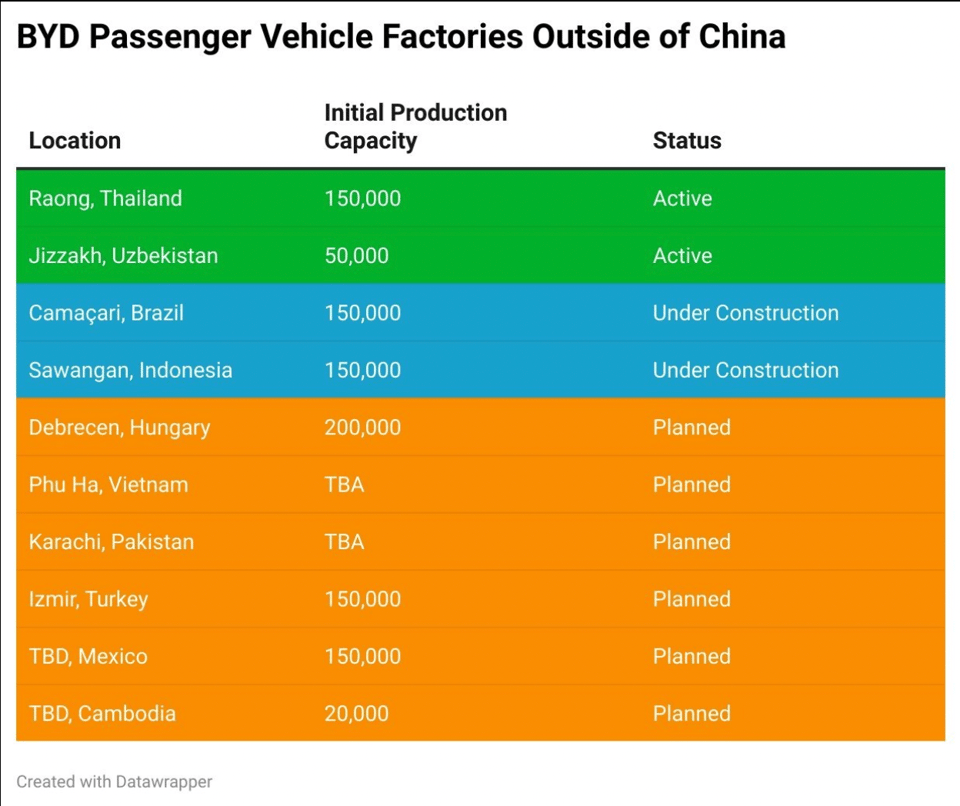

BYD overseas manufacturing via Esfandyar Batmanghelidj Global South countries are exercising strategic non-alignment; with India, Brazil and Indonesia demonstrating increasingly clearly in the last few years that they would not fall in line with either the US, EU, or a China-Russia bloc. A tipping point for the west, perhaps, was the freakout over the BRICS summit held a year ago; despite being dismissed in international media as a performative talkfest, US security advisor Jake Sullivan visited most of the existing and new members of the BRICS alliance in the preceding months in a “frenzied” schedule of currying favour.

Supply chains are key geopolitical battlegrounds & security strategies. This one needs little explanation. Wild swings in prices of battery components; barrages of reports on the lack of supply of critical minerals, and, most of all, the many many charts setting out that China controls a huge majority of the supply chain for dozens of the minerals needed for clean tech. Then there was the Covid logistics problem; the Ukraine invasion; and the Ever Given. See also, “The Geopolitics of Stuff”, our launch panel back with JFI/Phenomenal World in 2022.

The dire state of the international financial architecture and, relatedly, of finance for climate and development. Developing countries are fed up with the asymmetric access to capital. Even some of the larger and more powerful middle income countries are struggling with higher US dollar commodity prices (see, for example, Egypt). Smaller and poorer countries have been hit by Covid + higher commodity prices (reopening + Ukraine) + end of cheap credit + all coinciding with big debt repayments coming due. After years of the “billions to trillions” incantation, some things began to happen. The US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen advocated reforms to the World Bank’s lending capacity; some bits of progress have been achieved towards making Special Drawing Rights go further; Mia Mottley & Macron pushed some ideas in a Paris summit. But overall? It’s still dire; something which became undeniable when Larry Summers and NK Singh pointed out earlier this year that net flows are going the wrong direction: capital outflows to private creditors overshadowed the increased concessional lending to developing countries. Instead of billions to trillions, they wrote, it is “millions in, billions out”.

***

We think the Deese essay recognizes these developments and shifts; it doesn’t necessarily address them satisfactorily. But there are some blindspots. These two feel particularly stark:

The assumption that developing countries will be content to be US clean tech export markets: Deese’s essay draws straight lines between US green manufacturing prowess and US geopolitical triumph, via developing countries decarbonized with said US output. For Deese, the transition is “the largest capital formation event in human history”. But should developing countries simply buy green goods from the US, rather than make any themselves? Jonas Nahm honed in on this problematic assumption.

https://x.com/jonasnahm/status/1826544819222495604There must be a global buildout of green manufacturing capacity; an international division of labour; and technology transfer. Else there will be few takers for neo-colonialism.

Private finance is really not going to cut it. Deese says that while the Marshall Plan was financed with 90% grants; the new Marshall Plan could be the reverse. “an American approach would be market-based and therefore more efficient because it enables competition and encourages large investments of private capital.” The evidence for that is scarce, however. (See Advait’s wonderful slideshow for a refresher.)

No kicker. There is more critique to be made and many, many more ideas to be discussed. Let a thousand green flowers bloom.

Have a good weekend!

Kate & Tim.

Add a comment: