Global conjuncture; new extractivism

The new green New International Economic Order, and why you should be watching the Democratic Republic of Congo

Hello readers! This week we have: Tim’s thoughts on the new New International Economic Order; my attempts at dot-joining on DR Congo, critical minerals and great power rivalry; and the performativity of the hypothetical Mar a Lago Accord. It is our 37th edition. Please forward it, subscribe if it was forwarded to you, and tell us what you think (me here; Tim here). - Kate

Global Conjuncture

First up: listen to Tim and Ilias Alami of Cambridge University in a 2-parter on The Dig podcast about the Global Conjuncture: everything that is happening right now.

Here is an excerpt from the (forthcoming) part 2 that touches on a lot of what we’ve been writing, over the years, about Global South agency:

Developing countries are not passive victims in the polycrisis. They are actively trying to wrestle control over their destinies and reshape the entire world order that has locked them into a pattern of unequal exchange that we have been talking about. And with Trump blowing up the world order, there is suddenly more space for developing countries to work with China and the Europeans and the East Asians to create a new New International Economic Order (NIEO).

There are many actors amongst developing countries that are trying to reform this unjust order with new green NIEO proposals. But to give some specific names: Brazil’s president Lula and Barbados’ prime minister Mia Mottley, the Pope’s debt jubilee proposal, South Africa's green industrialization…

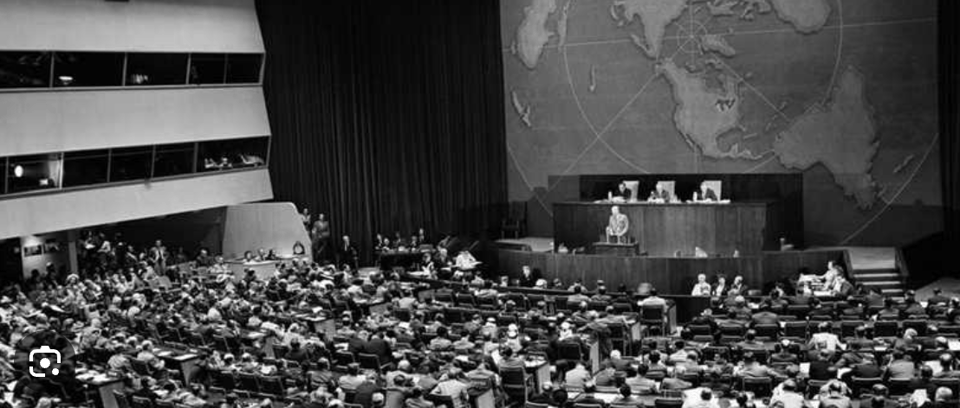

I was at the UN General Assembly in September of last year where Mia Mottley and Lula presented new proposals at the historic 50th Anniversary of the original 1974 NIEO proposals. What was striking was that in this era of collapse of multilateralism, they not only asserted the principles of equity, sovereign equality, interdependence, common interest, cooperation and solidarity among all States, but that they would work with everyone east and west, north and south, to rebuild a multilateralism that supports green structural transformation.

[…]

The first thing they insisted on was that deep decarbonization requires the structural transformation of both developed and developing countries. The energy transition is not going to be done by Wall Street but has to be led by states who want new growth models to transform their economies.

Decarbonization inevitably requires manufacturing—“a billion machines” to replace the stock of polluting ones. UNCTAD estimates that seventeen frontier technologies could create a market of over $9.5 trillion by 2030. So far, rich countries are seizing most of that value. How and where the manufacturing and supply chains of these goods evolve will shape the political economies of virtually every country in the world. The return of industrial policy is necessarily a contest over profit-driven commercial competition, the global division of labor, and distribution of economic power.

[...]

Because it's very clear that all development choices are really Climate Choices. You know, what kind of cities will Lula build? What kind of tropical green urbanism will Indonesia pioneer? Developing countries have a lot of development choices to make: and they could lock countries into a high carbon future or a low-carbon future.

Don’t say (billionaire edition) scramble for Africa

One of the questions about the new US administration is how it would treat existing programs with countries in Africa. One answer came with the dismantlement of USAID including the PEPFAR program which helped limit the spread of HIV and saved millions of lives, especially in Southern Africa.

Africa has become interesting to the US in the last few years for its “critical minerals”, which great powers have been jostling over ever since the Europeans and the US recognised that China controls much of the resources and supply chains for substances required for high tech and clean tech goods.

This week the Trump administration announced it would utilise a variety of tools – the US Export Import Bank, the Defense Procurement Act, the Development Finance Corporation (DFC) – to secure critical minerals (it also expanded the definition of this group to include uranium and gold). This isn’t a radical departure; the Biden administration had also used the DPA to secure minerals, including providing funding to Canadian and Australian miners.

During the Biden administration, the big US commitment on critical minerals in Africa was for the Lobito Corridor, which aims to connect the copperbelt of northern Zambia and southern DR Congo to the Angolan port city on the Atlantic Ocean. Angola was the only African country visited by Biden during his presidency.

Lobito Corridor is a complex project involving at least 7 Memoranda of Understanding between the US, EU, and governments of Zambia, Tanzania, Angola and the DRC; a consortium of commercial members including commodities trading house Trafigura is also party to a Lobito MoU.

The Trump administration hasn’t revealed a stance on the Lobito Corridor, but there so much speculation that the US would walk away that experts had to point out that the project would still continue even without American participation.

Meanwhile, commercial American interests in the region are growing. This week Bloomberg revealed that KoBold, a Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos-backed mining “AI” startup, contacted the Democratic Republic of Congo’s presidential office on January 21 offering to buy out a large lithium hard rock deposit in the country’s south. The Manono project is the subject of a complex dispute between a small Australian miner and China’s Zijin Mining Ltd.

Bloomberg reported that Kobold wrote to the chief of staff of DRC president, Felix Tshiekedi, and the company noted it is developing a large copper mine in neighbouring Zambia.

Tshisekedi saw which way the wind was blowing with the new administration and, in an interview with the New York Times last month, proposed a deal with the US:

The Trump administration has already shown interest in a deal that could ensure a stream of strategic minerals directly from Congo, Mr. Tshisekedi said. He also touted investments in major Congolese projects including a mega dam that, if completed, would be the world’s largest hydroelectric plant.”

The prospects for continuing US support for the Lobito Corridor, then, might be more positive than it looked a few weeks ago. The prospects for all the other partners, however, is less clear. And there are quite a few of them:

MoUs and Agreements Related to Lobito Corridor

EU, US, DRC, Angola, Zambia, AfDB, AFC MoU – Development of LC

Angola, DRC, Zambia Agreement (LCTTFA) – Trade and Development

EU, DRC MoU – Critical Minerals and Value Chain Development

EU, Zambia MoU – Strategic Minerals and Value Chain Development

US, DRC, Zambia MoU – Support EV battery value chain

DRC, Zambia Agreement – EV battery value chain

Angola, Trafigura, Mota-Engil, Ventricles – Concession agreement

There’s a “west vs China” narrative around competing transit corridors from the central African copperbelt which spans northern Zambia and southern DRC.

So what is it that China is already doing here?

Last year China announced it would support the refurbishment of the historic TAZARA railway out of Zambia to the Dar es Salaam port in Tanzania. TAZARA was originally built in the 1970s with interest free loans and 50,000 workers provided by Mao’s China.

This new commitment was to the tune of $1 billion, but it was to be a public-private partnership rather than the debt financing that China normally provides. Just last week, TAZARA said it was in talks with China’s CEECC corporation about a $1.4bn investment. TAZARA, which is owned by the Zambian and Tanzanian governments, quickly issued another statement to clarify it was a negotiation, not an agreement.

It’d be terribly remiss to not mention that all of this is happening amidst a continuing war in the eastern part of DRC. An armed group known as M23, which is backed by the government of neighbouring Rwanda, has this year taken control a section of DRC’s east, including the city of Goma, that is home to 3m people. The violence and displacement is horrific. The role of minerals and the fight over them is complex, but significant — a new essay from Jason Stearns explores.

Mar-a-Lago performitivity

The Mar a Lago Accord is the hypothetical new version of the 1985 “Plaza Accord”, in which US pressured its major allies to help devalue the dollar by intervening in currency markets to strengthen their own currency. Trump wants the US to run a surplus with other countries – which in part would require a weaker dollar (tariffs won’t help that). The “Mar-a-Largo Accord” is the supposedly coherent international macro-financial strategy can be found in the White House, assuming that the factions can be reconciled with each as well as with the actual workings of the global financial architecture.

The ideas it is based on are not well grounded in reality, however, and a lot of the writing on it is what Adam Tooze calls “fin-fi” (that is, a genre of fiction about… finance!). Brad Delong calls it sanewashing.

Mona Ali has a wonderfully clear illustration of how effective some kind of enforced dollar depreciation might be:

<The performativity of Mar a Lago>

This is the gargantuan size of the US external balance sheet. Cumulated trade deficits contribute to the negative net international investment position. To presume that an accord will smoothly uplift the NIIP is silly. Dollar depreciation helps reduce US foreign liabilities but if foreign governments are forced to buy US century bonds, it will only increase those liabilities. Net effect could be a wash unless the ESF (which is about $11 billion; tiny) continually purchases foreign currencies to balance out increases in US liabilities. It's performative accounting and doesn't get to the heart of global imbalances which are driven by entrenched inequalities in the global financial hierarchy and production networks.”

That is all from us this week. Thanks for reading, and please forward, share links, and tell people about it!

Add a comment: