Gen Z and One weird trick

Welcome to edition #13 of the Polycrisis Dispatch, where we’re mostly looking at “country platforms”. Our next Book Club is about Sinews of War and Trade by Laleh Khalili, will be discussed on August 28 at 830am EST We’re very excited that Laleh herself will be joining us for this one! Our Discord is here for ongoing discussion about the books and other topics, and planning the occasional Polycrisis meetup.

We’re still keeping this newsletter experiment low-key, and we’re at the three-and-a-half months mark now, so please: Give us feedback! Forward it to your friends! Maybe even share it on one of the less cursed social media platforms! You can contact Kate, Tim, or both of us by email.

Gen Z

This week, young people in Bangladesh drove out the country’s prime minister. Sheikh Hassina fled on a plane to India over a jobs quota bill that would have reserved 30% of public sector jobs for family members of veterans of the 1971 war with Pakistan.

Just a couple of months ago, we wrote about how Kenya’s Gen Z forced Ruto’s government to cancel a IMF-Kenya plan to introduce new taxes on everyday goods, and raise some existing ones.

Both these uprisings were heartbreakingly bloody, with authorities killing dozens in Kenya and hundreds in Bangladesh. Both were youth-led revolts against measures that threatened their economic futures.

Bangladesh, like many developing countries in a dollar-central world, suffered disproportionately from Covid and from higher commodity prices. Swathes of the population endured lengthy blackouts in 2022 when contracted LNG shipments were acquired by Europeans for higher prices on the spot market after Russia disrupted continental gas supplies. Bangladesh earns 84% of its export income from garments, but the statutory wage for garment workers is less than two-thirds of the typical household cost of living, according to the Anker Research Institute. In 2023 several big western clothing brands signed a Fair Labor letter to Hassina asking that the wage be increased, noting that it had not increased since 2019 despite a substantial increase in living costs.

Agency or distraction?

Bangladesh was one of the first countries to be designated for an IMF-supported effort at creating a country platform at COP 28 in Dubai last December, with a “climate and development platform” to improve project bankability and coordinate investments using funds from the IMF’s new resilience and sustainability fund (RSF), the Green Climate Fund, various policy banks, and private finance.

The idea of national “platforms” has been kicking around for several years in the development finance space, but received a boost from climate finance circles with the South African JET-P in 2022. It is now being bolstered by Brazil, which is advancing the platforms idea in its G20 presidency.

What does it really mean? Analysts at the UK thinktank Overseas Development Institute (ODI) in a 2022 series of papers attempted to unpick the different interpretations of the phrase and critically analyse them. They put the broad definition like this: “… a government-led partnership that aligns international and national goals, thereby unlocking international finance (public and potentially private) to support a step change in climate action.”

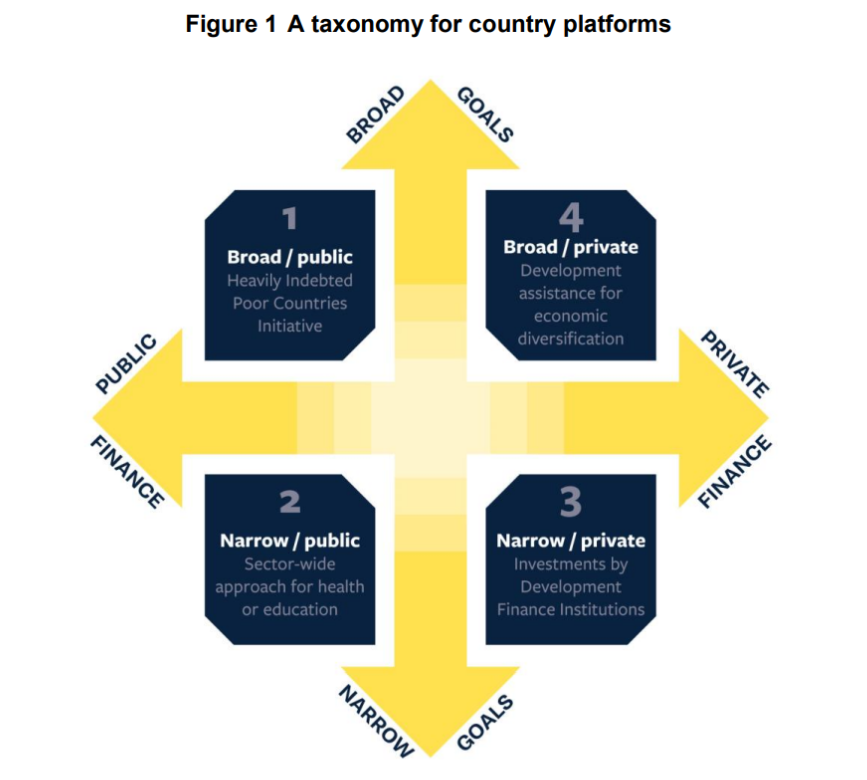

ODI proposes a taxonomy of country platforms, to navigate the different goals and sources of finance:

This schematic helps identify the main components of the concept. We’d propose that a more narrative view of country platforms would break down into three key stories:

1) Coordinating foreign aid and concessional finance; solving MDB tunnel vision

The idea here is to have some country-level alignment between the different sources of development finance; from bilateral aid to MDB loans and other facilities such as climate funds. MDBs are particularly in focus here as they traditionally lend for projects evaluated discretely, rather than funding longer-term, systemic changes. In an April joint statement, MDBs declared that these platforms would be a priority for them going forward. That would be a significant change in the way they operate.

2) A one-stop-shop for investors - especially private finance.

The G20 Independent Experts Group report from 2022, which the MDBs’ letter cited, illustrates another aspiration attached to country platforms:

“A key purpose of country platforms is to create an environment where investors have confidence in the realization of returns and management of costs where each depends on the actions of other investors.”

At COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, Mark Carney’s GFANZ alliance published a short note on the topic.

“Specifically, it requires building new country platforms which deploy blended finance at scale, leveraging private finance at significant multiples and connecting stand alone private finance with NDCs. These ‘Country Platforms’ would provide a single focal point to channel technical assistance and public and private finance to support the delivery of Paris-aligned NDCs in EM&DCs. They would coordinate and scale all elements including, critically, standalone private finance to major EMs for all aspects of transition finance including the wind-down of stranded assets.”

3) A means of sovereign financial agency

Setting national priorities that might then be used to direct concessional or commercial finance is naturally attractive for the governments of developing countries. Brazil is advancing the idea through its G20 presidency this year, and many other countries have indicated their support for that agenda.

The risk with country platforms is that what might be a sensible operational improvement – making development and climate finance less ad-hoc, more coordinated, and aligned with the country’s own strategic goals – becomes instead a kind of short-hand for “a trick to fix everything so that the country is more investable”. That’s especially dangerous if it’s seen as mostly applying to the country side of the equation, rather than to the finance supply side. Even countries with exemplary governance, institutional capacity and social and political harmony are subject to the international financial architecture, not least the currency and debt rules, and the shift from risk-on to risk-off of global capital markets. And for their part, foreign investors are often subject to numerous regulatory and cultural constraints that have little to do with the degree of national coordination in countries they might invest in (Advait Arun described these constraints for us last year, and a recent report from Finance Watch analyses the constraints specifically affecting European pension funds and insurers).

Credit ratings agencies and Africa

There was some epic reporting by Reuters last week about the effect of sovereign credit ratings on sub-Saharan Africa, and how a push by UNDP and US State Department to get sovereign credit ratings for the SSA countries over a decade ago had very different consequences to those expected.

The idea was that if the big three (Moody's, Fitch, S&P) initiated ratings on countries like Ghana, Rwanda, Ethiopia, and Cameroon, it would unlock finance that had been previously inaccessible to the countries. The ratings enabled countries to issue US-dollar bonds at high interest rates to investors seeking higher returns in a low-interest world. But markets respond to events beyond the country itself, and investors are driven by their own factors. When Covid hit and the investment environment changed, creditors fled. Many of the SSA countries whose entrance to the bond markets was facilitated by well-meaning agencies now have interest payments bigger than their social welfare budgets -- accompanied by predictable social deprivation and upheaval.

Reuters’ reporting suggests there is no smoking gun that proves bias against African countries in the ratings; although it does contain claims that the ratings agencies staff are prone to be disparaging about the “frontier” markets. The agencies certainly seem incurious about an entire continent in which they rate dozens of sovereign entities – only Moody’s and S&P have any offices in the continent; and they are limited to South Africa.

The US paid for Fitch to begin rating SSA countries; UNDP paid for S&P to begin. A UNDP official said that, early in the process: "...doubts about the African nations’ ability to meet the demands of the rating process were outweighed by the belief that “having their sovereign ratings done is a positive thing” for meeting development goals."

It’s a cautionary tale about believing in “one weird trick” to unlock finance for countries that are in the financial periphery for complex structural and historical reasons. Country platforms, at least in the best interpretation, might be sufficiently broad and ambitious to avoid that trap.

Add a comment: