Electrify everywhere: Renewable energy trade edition

Greetings and welcome to our 19th edition. There was no Dispatch last week as we published a big Polycrisis essay-newsletter on the new, green “Marshall Plans” that have been proposed by both US and Chinese policy elites.

We asked if these plans will be good for climate and development; and what is the likelihood of them being realised (rather than remaining wishful thinking around Great Power rivalry and domestic politics) let alone in a way that Global South countries want (rather than projecting said rivalry and politics onto passive export markets)?

The essay built on Tim’s Non-Alignment-as-bargaining-chip essay from 2022 and our essay about the 2023 BRICS summit, Grievance and Reform to conclude: Marshall Plans continue to be a mirage; the marriage of decarbonization and development requires far more internationalism than political coalitions than either great power is currently willing or able to underwrite. No more grand hegemonies, just permanent hustle, as Tooze put it last week.

Cleantech leapfrogging, with free trade?

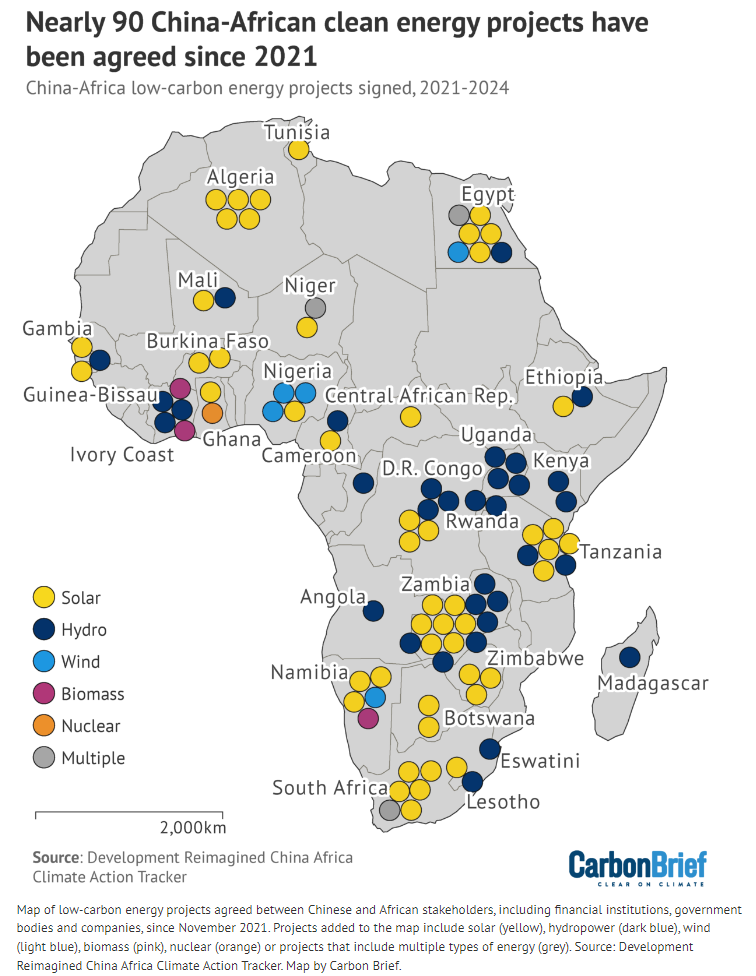

Into this sparse landscape comes some new analysis demonstrating that the Global South, and Africa especially, can become a clean energy success story even without much change in stance from China and the G7. This is not about becoming export superpowers with ammonia or the fertilizers or steel of domestic green hydrogen-powered industry; but clean electrification and energy access by simply taking advantage of technology, export rivalry, and trade measures – a kind of unorchestrated Marshall Plan.

The vast African “clean energy potential” has been proclaimed for years, usually centred on these facts:

Africa has lots of clean energy potential in terms of land, sun, and wind.

Energy poverty remains a big problem in many African countries.

Clean energy is becoming ever cheaper relative to fossil energy.

Thus Africa can leapfrog costly, dirty fossil fuels and skip straight to clean energy, as some countries did with mobile phones versus landlines.

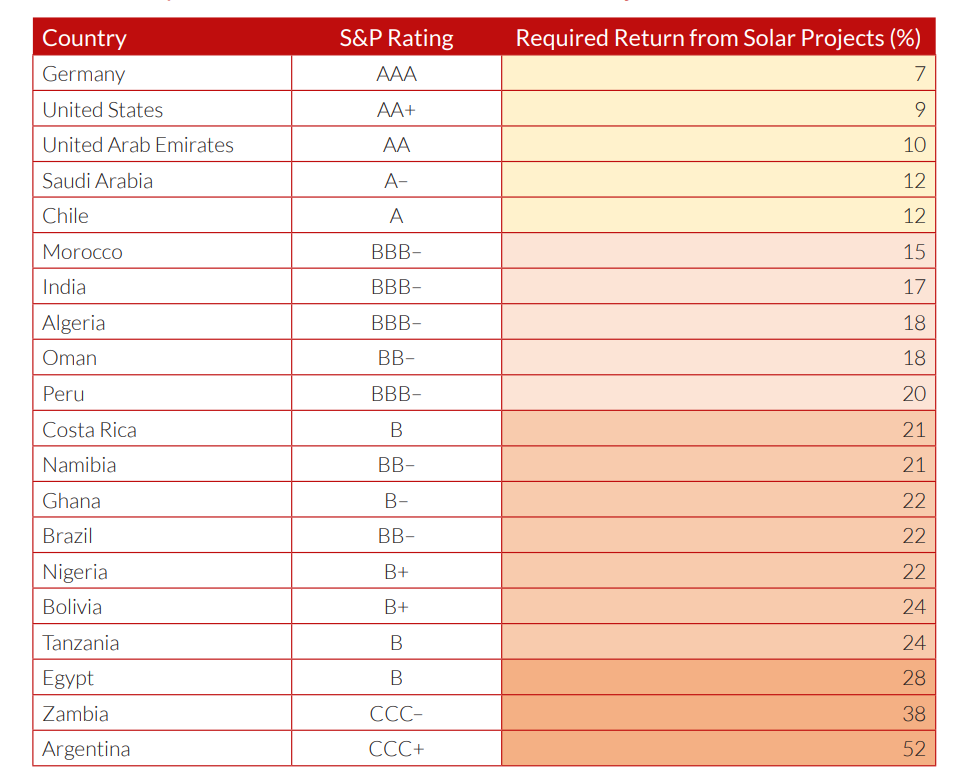

The logic is sound; one big problem, however, is that developing countries pay a higher cost of capital in general for energy generation and infrastructure.

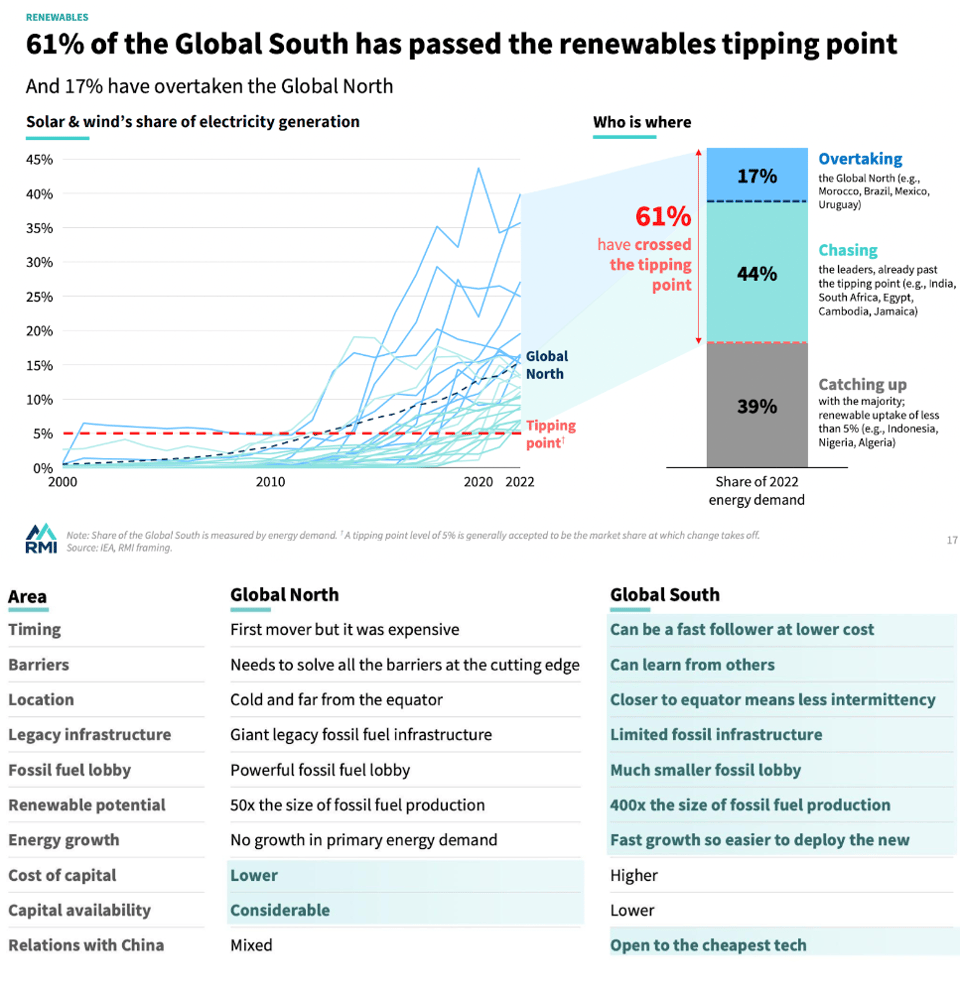

A new RMI report argues that Global South countries overall are actually doing relatively well at RE investment, deployment, and electrification — and are positioned to do even better, despite the cost of capital problem.

This finding is unexpected for us: "renewable energy generation has grown at a compound annual rate of 23 per cent in the global south, versus 11 per cent in the world’s richest economies".

Importantly, their definition of Global South excludes “greater China” (China+Taiwan) and the Gulf petrostates. Even while this grouping leaves in a number of petrostates and net fossil fuel exporters in Africa and Latin America, the vast majority of Global South energy demand comes from net energy importers and thus have a lot to gain from replacing expensive and dollar-hungry oil and gas with home grown clean energy.

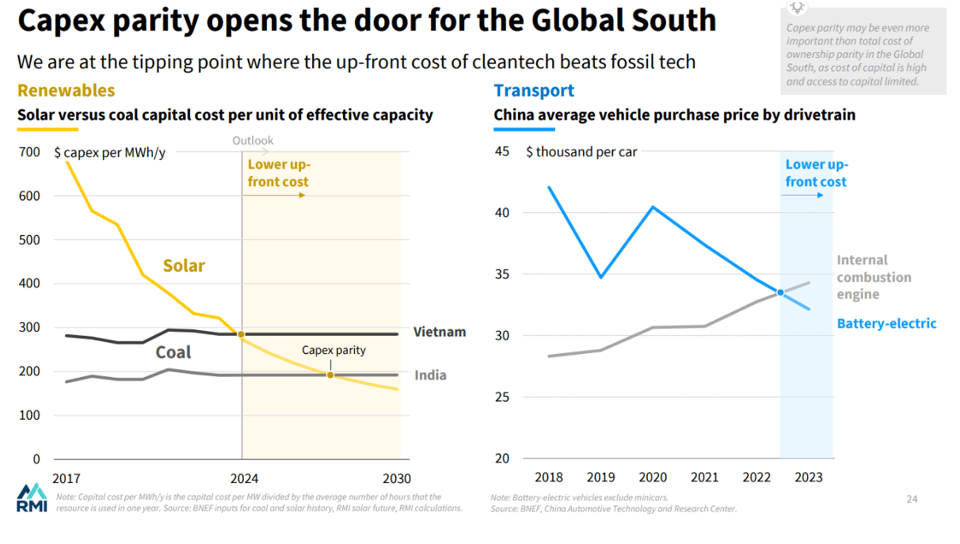

The RMI report does address the question of higher cost of capital for developing countries, but it identifies a measure by which that problem is being neutralised: “capex parity” for clean tech has been reached or is in sight for many countries:

If things are so rosy, there would be much less to worry about in regard to development or meeting climate targets.

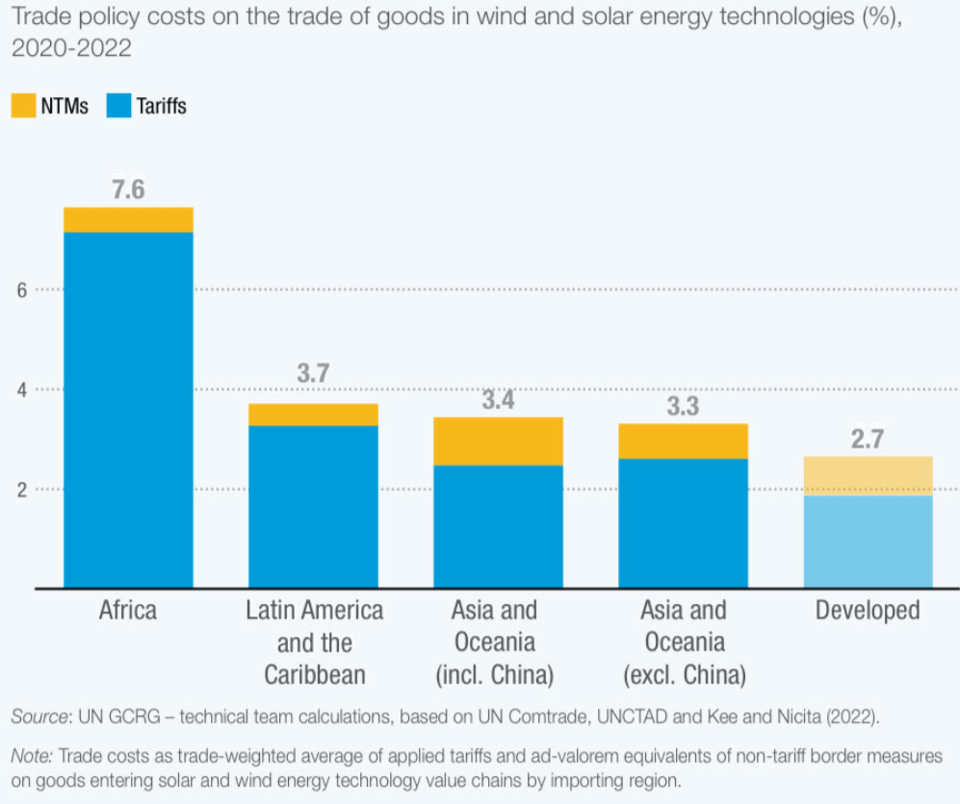

A new UNCTAD report however points out that many countries aren’t taking advantage of this cheap RE gear flooding the markets, and are in fact blocking imports with high and unhelpful tariffs. This is particularly the case for African countries:

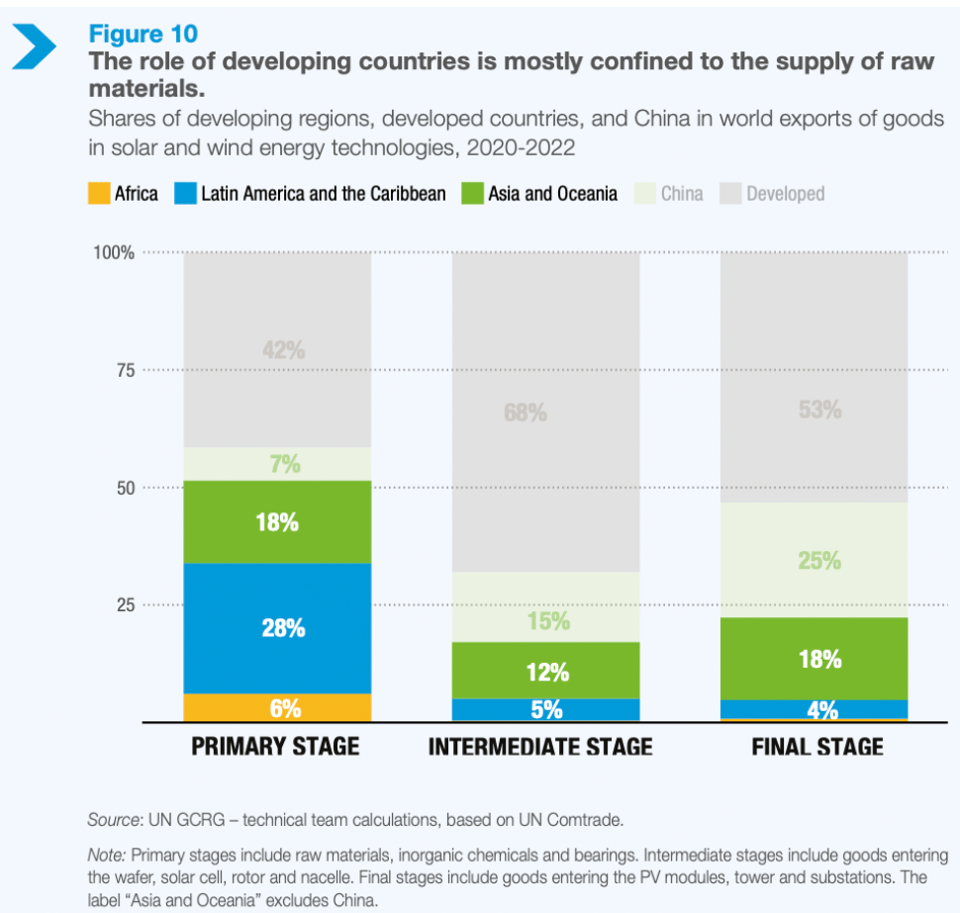

These tariffs have done little to help countries avoid the seen in earlier industries. UNCTAD warns, “Developing countries are slipping into traditional trade patterns, acting as net exporters of raw materials for solar and wind energy value chains, but net importers of manufactured goods.”

What is being fashioned over the next decade is either a neocolonial or a new international economic order. So what is it going to be? Concentration into even fewer hands and rich countries get richer, or clean energy accompanying better distributions of production and wealth?

In considering the energy needs of each country, the UNCTAD report says this is less of a tale of mercantilist woe, and more one of development opportunity.

African tariffs on renewable products are particularly high, and UNCTAD points out that they are not protecting any domestic infant industries in clean energy, because those largely don’t exist.

Talk of moving up the clean energy value chain in Africa often focuses on the raw commodities end of the process. Indonesia’s export ban on raw nickel (and the resulting influx of investment into processing facilities) is often cited as an example, and UNCTAD recommends resource exporters make efforts to keep more stages of the supply chain, both in this report and at more length elsewhere.

But what this new report emphasises is the good opportunities in the intermediate stage of solar and wind production, such as assembly (we’d note that the same is true for EVs, although they are not in the report’s scope).

Trade in intermediate solar and wind products today is heavily concentrated, as the chart below shows:

This is where UNCTAD suggests there is an opportunity:

The assembly stage can enhance the integration of developing countries into renewable energy value chains beyond raw material supply. In assembly, these countries could benefit from labour availability, lower technological complexity, and the ability to import inputs and export assembled goods. Southeast Asian economies such as Viet Nam, Malaysia and Thailand have developed significant assembly capacity, by leveraging their cost advantages, trade networks, and domestic policies (such as feed in tariffs) to attract investors from big players, such as China. In the wind energy sector, opportunities for job creation are associated with nacelle assembly and its subcomponents, such as generators and gearboxes. Developing countries like India and Brazil have been establishing nacelle assembly facilities to tap into these opportunities.

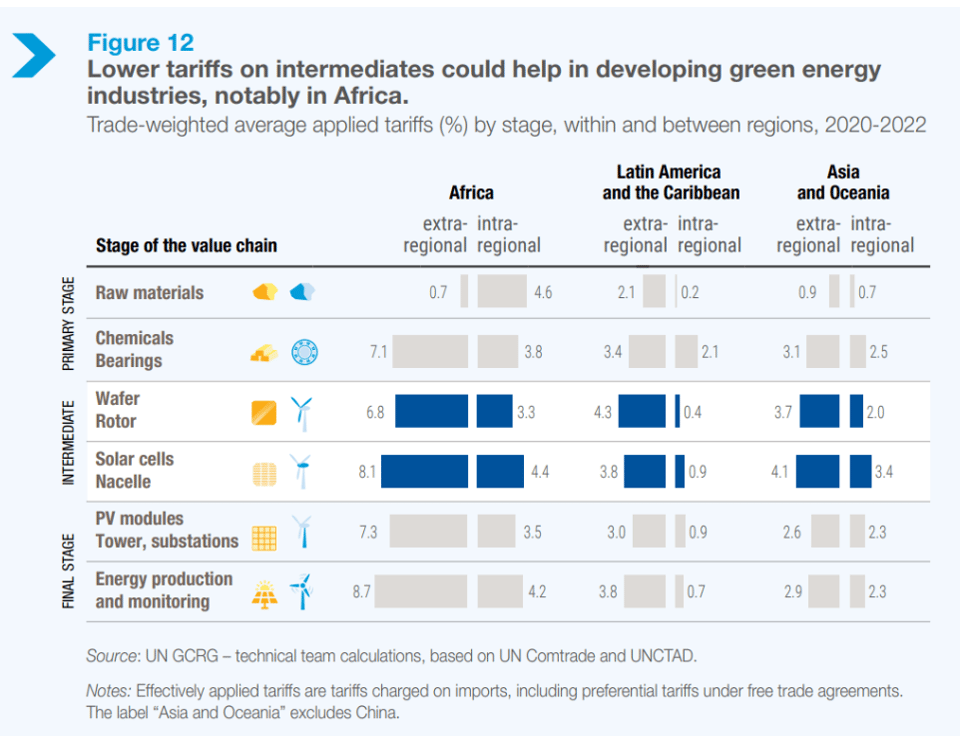

Lowering intra-regional tariffs would also assist with this intermediate cleantech industrialisation, by creating access to bigger markets. On that front, too, African countries have a lot to gain – as does Asia, where intra-regional tariffs have been increasing recently:

Cutting tariffs and cheaper components doesn’t obviate the challenges of finance, however, especially for countries with enormous debt servicing costs and facing a bleak outlook for overseas development assistance and concessional money. A forthcoming book tracking decades of public-private partnerships in development finance concludes that – surprise! – a massive mobilization of private finance into Global South infrastructure hasn’t occurred.

***

Report-mageddon

The number and magnitude of world events taking place in the next couple of months is matched, numerically at least, by the volume of reports. Here are a few from this week that are very worthwhile reading:

“Of the 51 current IMF programs, 40 include budget cuts of 3.3% GDP on average.” The IMF is still imposing austerity at a furious rate, energy loans are increasingly conditioned on privatisation and fossil fuel production. (Re-Course)

African countries’ debt has grown 240% between 2008 - 2022. By 2028, 14 countries are expected to breach solvency thresholds. (DRGR)

The IEA World Energy Outlook aka energy bible is out… and fossil fuel demand is expected to falter to 2030, under most scenarios.

Looking ahead to next week: a preview for the BRICS and IMF/World Bank annual meetings by Rachel Ziemba.

***

That’s this week’s edition! You can email us here (Kate, Tim)

Add a comment: