Domestic politics and planetary change

Brazil's new politics of taxation is a big deal

Welcome to the Dispatch, which is not coming to you from the 30th UN climate meeting in Belém, but is mostly about Brazil. Brazil is important on the international stage for reasons well beyond COP, and it’s also very close to Tim’s heart right now as he’s been advising several parts of the government on green industrial strategy over the past year.

Coming up this week in the Phenomenal World / Polycrisis series is an excellent essay on plastics by the historian, Venus Bivar.

-Kate and Tim

First: Brazil

There are several things you will hear a lot about in relation to Brazil as COP host over the next couple of weeks; they’ll include Belém being a terrible choice of host city and, inevitably, the decision, just weeks before the climate summit, to greenlight oil exploration near the mouth of the Amazon.

There is more to this than just an awkward juxtaposition or a development-vs-environment contestat.

Almost three years ago, in our second ever Polycrisis essay for Phenomenal World, we wrote about the upcoming COP27 and Brazil’s newly returned-to-office President Lula and asked whether the new Brazilian government have a bigger effect on the climate than the UN climate conference about to take place in Sharm-el-Sheikh? Simply enforcing the country’s forest protection law would be material for its emissions (and appear to have happened). But an agriculture export boom of the last 15-odd years has bolstered the power of big agriculture; and the state-owned oil producer is an important source of public revenue.

We wrote that Lula would:

… have to pick battles from his ambitious agenda of social housing, greening agro-industry, and transitioning Petrobras, the national oil company.

The new Lula government will have to contend with homelessness, unemployment, and more than a quarter of the population living with hunger. But backed by housing movements, Lula aims to expand social housing and public-transit-oriented green urban development. Any success would serve as a model for other middle income democracies.

Crude oil is also a significant source of Brazil’s export income, not far behind soybeans. In a late-March interview with Time, Lula dismissed talk of ending national oil extraction. But a Lula government will exert more control over Petrobras, seeking more domestic refining capacity and a vision like that of European oil majors who are declaring themselves “integrated energy companies” that make renewable electricity.

Last week, Lula’s PT achieved a huge step towards squaring that circle: getting enough parliamentary support to tax the rich more, and stop taxing the poorest workers altogether.

The tax-free income threshold for workers will rise from 3,091 reais to 5,000 reais per month, exempting 25 million people from paying tax; while the rate will increase for those paid more than 600,000 reals/year and dividends (currently exempt from income tax) sent abroad will be taxed at 10%. Some challenges remain: another measure or two has to be passed to offset the cost of cutting the tax take from lower income people, and these are contentious (the banking and fintech sectors are fighting against plans to tax them more).

But the precedent has been set: the rich will be taxed more, and the opposition supports it. The Bolsonarists, whose claim to being the party of sovereignty was battered by their support of Trump’s attempts to interfere with their former leader’s sentencing, were forced to accept the new tax framework in order to boost their flailing popularity. This may be more important than the decision to try to draw down more revenue from the country’s oil reserves. (Every country with oil does that; but few have built political consensus about a new and equitable source of fiscal space).

There'll be many pieces and op-eds about the complex moral politics of drilling in the Amazon and using some of the proceeds for green industrialisation and forest preservation. How many of them will mention the fiscal reform and tax-the-rich agenda? Or that this will likely guarantee the electoral success of the PT (Workers' Party) in the 2026 national election and hold the Bolsonaroists – who’d be far worse for the Amazon and for climate generally – at bay? The country is on track to reach a primary fiscal budget (ex-interest costs) surplus next year; inflation appears to be settling; and Lula is the most popular leader in Latin America ahead of the elections in 2026: more than 80% support the tax cuts for the poor, and almost two-thirds support taxing the rich more.

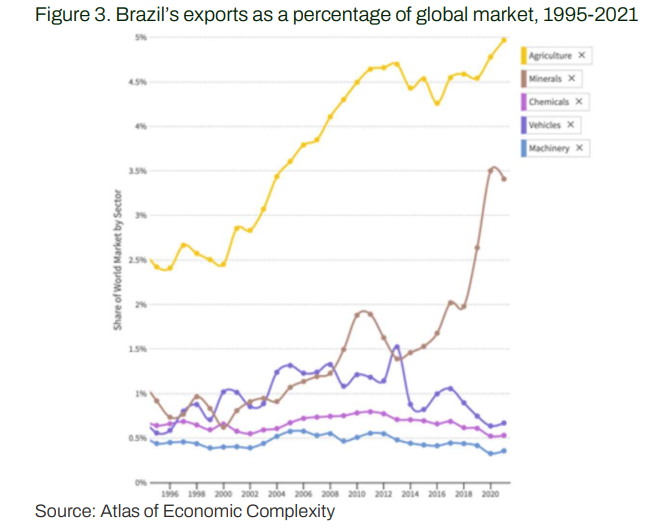

Brazil is one of many countries that de-industrialized since the 1980s. In the 1960s and 1970s the state developed high-end manufactures like airplanes and biodiesel cars. In the 1990s that began coming apart in earnest as industrial strategy was abandoned; and during the 1990s and 2000s the commodities boom saw Brazil’s “reprimarization” as exports of soybeans and crude oil and other extractives soared.

Development, and green development especially, entails large and front-loaded capital requirements. Brazil’s “NIB” industrial policy framework gives cheap credit to sectors arranged in orchestrated missions; as well as tax breaks and preferential government procurement for locally manufactured, sustainable purchases. For Brazil, there are limited ways to do this in the near-term, and they come down to: tax the rich, or sell more of your resources.

Brazil is like any other country in this way: sustainable politics at the national level is critical to getting through any good measures to cut emissions – and to ensuring they’re sustainable.

International commitments made will not be effective without sustainable domestic politics within each country that makes these commitments. That isn’t an excuse for cynicism — our point is that climate policy is inherently political. A lot has to change to cut GHG emissions. A lot of things have to be built, as well as things being retired, and shut down. There will be winners and losers. By securing a bipartisan political win to get a chunk of the money from taxing the rich more, Lula’s PT is able to realise a source of income that many governments in both rich and poor countries struggle to access.

The TFFFFFFFFF

One of the Lula administration’s big goal as the country hosting COP30 is a project called the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) to reward developing countries for preserving their forests that keep vast amounts of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

The plan is that the fund will get paid-in capital of $25 billion from wealthier countries. It will then issue $100 billion in AAA-rated bonds. The proceeds from that are invested in higher-yielding, lower-rated debt from emerging market countries. The spread between the lower repayments that the fund makes to its own bondholders, and the higher repayments it received from its own investments, becomes the money that is then allocated to developing countries that preserve their forests. The idea is a kind of mini-lateral hedge fund that uses sovereign credit ratings arbitrage similarly to multilateral development banks to make enough investment returns such that wealthy countries and donors make a small rate on their investment, while the earnings above that rate are directed to poor countries that preserve their carbon-sinking forests.

If cutting emissions is something that has to be done, and has upfront costs, then shouldn’t countries that forego short-term revenue to maintain carbon sinks be compensated? There’s a history of developing countries seeking compensation (Gabon, Indonesia) and even for curtailing oil production (Ecuador, Colombia, Angola).

We are usually pretty sceptical of addressing climate change and/or development with cute financial structures (see: sovereign green bonds, parametric insurance and debt-for-nature swaps) because they rarely address anything systemic and their distraction potential is high.

But better — the TFFF will apparently invest in emerging market assets; and to use the irrationally high premium placed on EMDE debt to earn income that is returned to some of those same countries who financial subordination. A bit like the ideas of Avinash Persaud — which include a way to get around the high premium on FX hedging for developing country currencies — this TFFF is not upending capital markets but it at least pushes in a direction that acknowledges the underlying, often arbitrary, constraints that are holding back green development.

New energy takes, same as the old

In the land of big Energy Takes, Jason Bordoff and Megan L. O’Sullivan have a sweeping piece in Foreign Affairs about the new energy landscape.

They argue that the big risk now is that oil and gas users are becoming more vulnerable, due to a combination of:

- renewed willingness to weaponize energy supplies not seen since the original OPEC embargoes (this has been going on for quite some time as anyone will know)

- demand is increasing not decreasing

- supply becoming constrained as US shale resources peter out (for geologic and economic reasons)

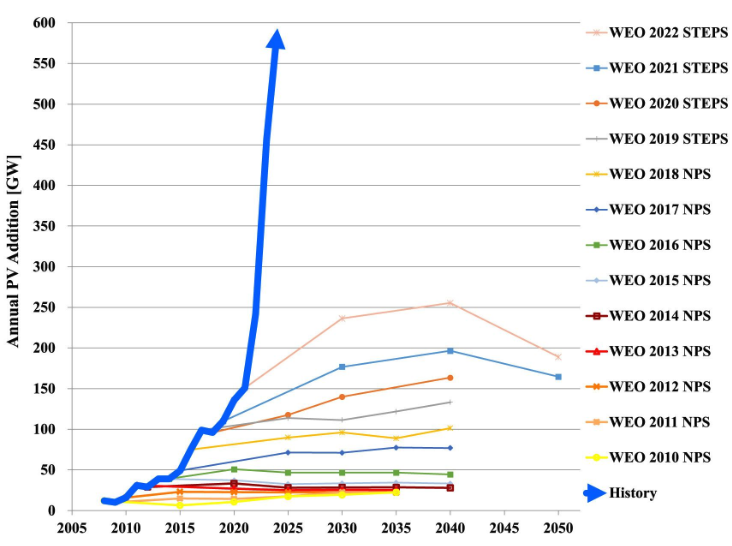

Much of their central thesis rests, weirdly, on the idea that oil demand will increase in the years to come. The evidence for this is a very poor reading of the difference between the 2024 World Energy Outlook from the International Energy Agency, and the (reportedly) 2025 WEO, which is released tomorrow. It’s not clear why these people wouldn’t understand that those two scenarios are based in very different assumptions: Current Policy Scenario assumes no new policies and no implementation of existing policies; in that sense it is the only WEO scenario that we can be 100% certain does not resemble the future. STEPS assumes only current policies will be implemented. It’s not an apples to apples comparison — unless journalists and pundits merrily carry on as though these differences don’t matter in some kind of effort demonstrate their hard-nosed realist credentials. There are many other reasons not to read too much into IEA scenarios anyway — for example, they rest on technical assumptions that, unlike the policy assumptions, are opaque. We shouldn’t need to tap the sign about the problems the WEO has had with solar in particular:

As well as mischaracterising the WEO scenarios, the piece makes much less of the truly interesting trends that are happening in energy. Developing countries going hell-for-leather deploying cheap Chinese solar; India rapidly ramping up its solar manufacturing; data centre demand/overbuilding risks, the increasingly frantic actions of highly oil-dependent exporters, and an unpredictable LNG gas market outlook would be just a few thing that might be worth looking.

Instead, Bordoff and O’Sullivan see dangers everywhere in the deployment of clean energy: international electricity transmission, for example, could be weaponized (yup) and, for those who have been under a rock for the last few years, they point out that China’s control of the supply chains for many transition minerals creates another source of potential instability and vulnerability. At this point, though, they do catch up a little and point out that China’s clean tech supply chain dominance is rather less effective as a tool than controlling large portions of global oil markets or their shipping routes.

The conclusion is that clean energy has some benefits under the current geopolitical vibes, so climate goals and energy security goals might indeed have something in common. Who knew?

OTHER STUFF:

The Soviet world view embedded in UK energy policy (Bloomberg Zero podcast)

An amazing FT investigation of what happened to Neom, Saudi Arabia’s ultracity-in-the-desert plan:

“[one architect warned] of the difficulty of suspending a 30-storey building upside down from a bridge hundreds of metres in the air. “You do realise the earth is spinning? And that tall towers sway?” he said. The chandelier, the architect explained, could “start to move like a pendulum”, then “pick up speed”, and eventually “break off”, crashing into the marina below.”

Australians will get free daytime electricity through the grid thanks to extensive rooftop solar deployment.

The destruction of USAID has cost 600,000 lives (New Yorker). Apart from the horror of it all; people around the world will hear about this – probably a lot more than people in the US and other rich countries.

More on Brazil from The Break Down - “Lula’s Dilemma” by Sabrina Fernandes.

Us, elsewhere:

Tim’s Johns Hopkins lab work was quoted in the NY Times today about China’s green power exports; and Kate was on a Chatham House/Strategic Climate Risk Initiative panel on “derailment risk” (video).

Thanks for reading! You can email us (Kate here; Tim here); follow us on Bluesky (Kate, Tim, Polycrisis account); join our discord channel and, yes, do something on LinkedIn.