Costing climate policies

Welcome to the 4th edition of our test-mode Polycrisis Dispatch. This one is going out on a Friday rather than the Thursday we were aiming for. (Last week was big for all of us!) Today, we look at some of the numbers that are calculated about the cost of climate policies, and what is frequently missing from these numbers. We could say much, much more on this topic - it’s vast - but we hope this gives a sense of key things to look for. Please email us mailto:asahay@gmail.com and mailto:kate@katemackenzie.net

Costing the climate

How do you count the cost of future efforts to cut emissions? It’s a question that has dogged climate mitigation forever, and with the mid-transition messing with us all, it’s a topic that we can expect to be prosecuted in ever more granular ways.

Lots of big numbers are thrown around about the amount of dollars needed to decarbonize the world. Who pays these costs? What are they anyway - are avoided costs accounted for? Operating cost savings? Rarely.

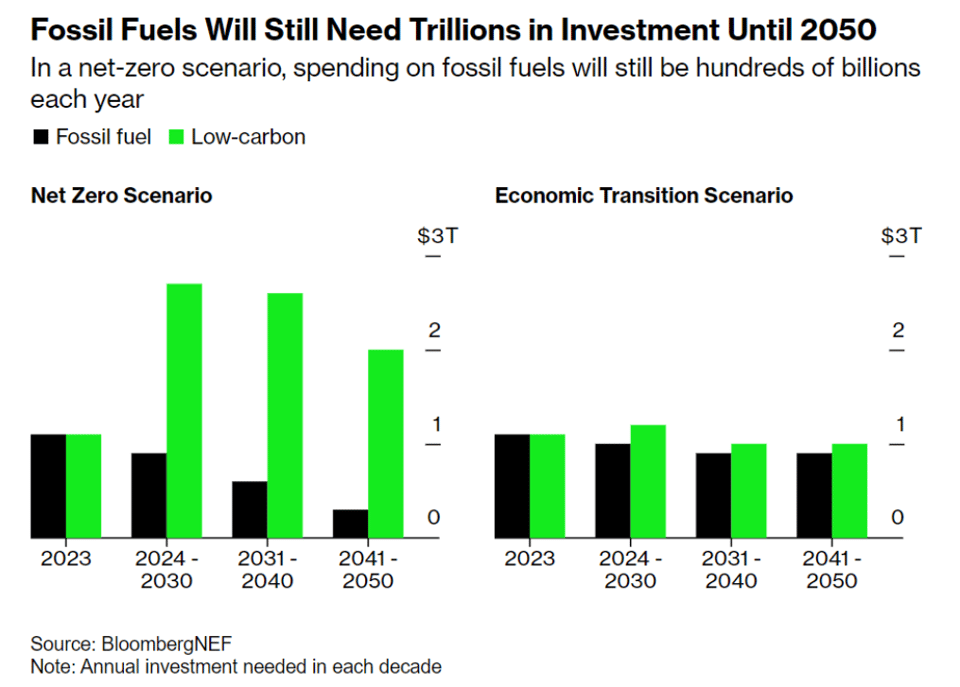

Bloomberg New Energy Finance published a big scenario exercise this week and found that the investment needed for “net zero by 2050” would require $34 trillion more upfront investment than BNEF’s version of business-as-usual. The cost is $215 trillion through 2050, versus $181 trillion for the BAU.

The business-as-usual (actually called the Economic Transition Scenario) assumes that governments aren’t going to ramp up their policy action at all, but technology will improve a little to make decarbonization somewhat more cost-effective without policy measures.

CAPTION: We can snip Bloomberg images with impunity because this is a Limited Newsletter.

Problem is, as the authors of the Bloomberg news story note, the BNEF report only estimates capital expenditure. They don’t take into account the operating costs, which almost certainly works in favour of a BAU scenario – because fossil fuels are expensive operating costs in most situations, which clean energy systems don’t have. In other words, the BNEF estimates are only looking at upfront cost with no view of the continuous costs of buying fossil fuels.

While we have not been through the 18 million data points in BNEF’s report, there are lots of other points we can make about this kind of estimate.

Technology moves quicker than you can stay pessimistic1

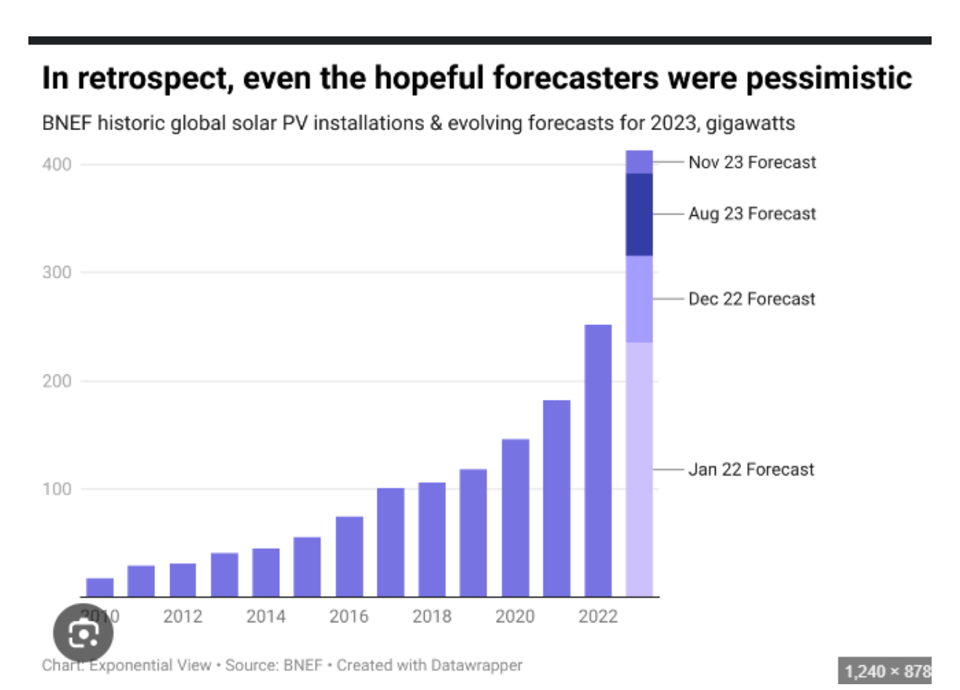

Firstly: all of these scenarios rely heavily on assumptions about the rate at which technology will advance and costs will fall. You might think that BNEF would be among the most optimistic of the big energy forecasters on this front, but they’ve not been a lot better than anyone else (IIRC, it was only the Greenpeace ®Evolution scenario which ever got close to accurately predicting solar cost declines).

This chart shows that they really missed the big solar installation boom last year in China, Vietnam and other countries (including the US):

CAPTION: This is from “Exponential View” by Azeem Azhar, it’s a subscription post but somehow Google Images let us see this image so we didn’t have to make one ourselves.

No, faster cheaper technology doesn’t solve everything.A billion machines is necessary but not sufficient for the transition. But it counts for something.

Energy geopolitics is utterly unpredictable

Did anyone predict that the next phase of China’s economic growth miracle would be producing boatloads of cheap, nifty EVs? China’s central government wants energy security almost as much as it wants a population that can be kept compliant with adequate jobs and growth.

Costs are different for governments

You can estimate costs in many ways and the private sector is great at lowering them and passing them onto governments; but governments can borrow more than they think.

Developing countries without financial autonomy are in a tougher spot. Yes, self-imposed austerity is a problem. All over the world governments are beholden to ideas of austerity which may not actually prevail forever.

Even if they do, it is possible to get around. When an austere government and an energy industry love each other very much they can come up with all kinds of financial off-balance sheet engineering. That, friends, is how green bonds and their older siblings, social bonds, were made. At least, in rich countries.

If we looked at operating costs what would be different?

If we take fiscal constraints as given – for now – and want to bring down the “costs” of investing in climate measures, then scary big numbers such as BNEF’s are little help.

A brand new paper from Oxford Smith School attempts a more measured approach to costing policy measures — just for the UK.

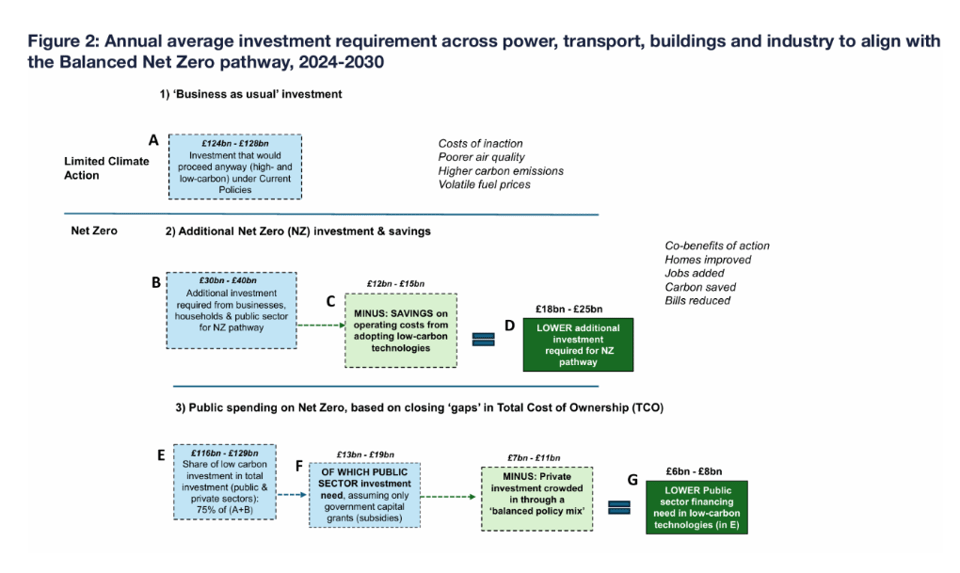

Firstly, it finds that additional investment costs for the UK's 2030 climate goals are only 25% above what would have to be invested anyway in energy and other infrastructure and energy consumption (replacing cars, for example). That number is a bit higher than BNEF’s 19%.

In GBP, it’s an additional 30-40bn for the years 2024 through 2030, on top of 124-128bn.

However, including the savings from operating costs brings that 30-40bn down to a much lower 18-25bn range – or as low as 14% of additional spend to get green rather than polluting investments..

Even leaving aside the operating cost savings; only some of that total expenditure is specifically for low-carbon measures, and only some of that portion needs to be public expenditure. That leaves £13 - 19bn, but, the authors write, if public support is not entirely provided as direct grants and subsidies, it can be reduced further to £6-8bn per year.

The analysis is also sensitive to cost and availability of capital to different “actors”. The investments that end up needing public spending support are mostly heat pumps and retrofitting - investments often made by households, which tend to need a shorter payback period than governments and businesses. It also considers “high interest rate” and “low interest rate” pathways.

They conclude that the extra, public investments for climate policies would total £13-19bn per year if directly subsidised, and those costs can be addressed using just £6-8bn pa of government expenditure by measures such as 'crowding in private capital' and - um - raising the carbon price.

The schematic is excellent:

Will the public of the UK, or indeed any country, be able to consider costs in this level of detail?

So far it has been hard for “climate policy costs” to be considered even against the much higher (with upside risk) costs of not taking climate action. As BNEF notes, their (high level, over-egged) costs neglect that too, and are likely to be eclipsed by the costs of climate impacts.

That ends our fourth weekly Dispatch – if you have thoughts on it, please do let us know what they are!

Does this joke work? Surely there’s something there?

Add a comment: