Autarky or resilience or chimera

Yet another acknowledgement that private finance doesn't really do development; plus China's latest energy transition milestone.

Welcome to the latest Dispatch, the weekly newsletter that is rapidly decoupling from the Gregorian calendar. This edition looks at yet another acknowledgement of the limits of trying to lure private finance into development; the IMF’s destructive prescriptions in sub-Saharan Africa, and then: how China’s energy system hit a new milestone in decarbonization (with seemingly no reliance on private finance mobilization). We are getting ready to travel next week for the Beyond Neoliberalism conference, among other things, so it may just be a very short edition next week. In the meantime, we are on Bluesky and there’s also the Polycrisis discord. Or email us here (Kate) or here (Tim).

***

Just over a year ago, Larry Summers and NK Singh pointed out that the aspiration of channelling “billions to trillions” for developing countries with the magic of private finance had failed, and had instead become “millions in, billions out”, with capital flows from Global South to North exceeding those in the other direction.

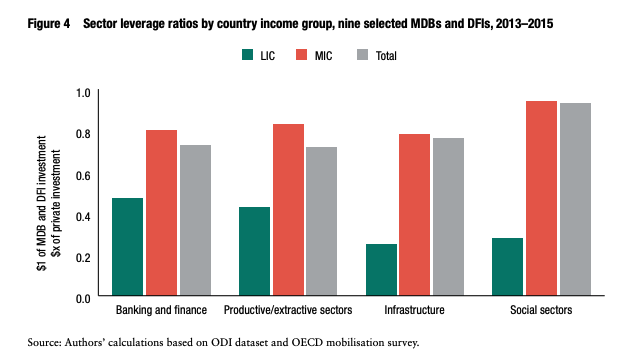

We thought if that might be the moment of reckoning for the almost religious conviction that “unlocking private finance” was the key to boosting developing countries’ prospects. We may have been wrong. A few days ago The Economist – surely an influential publication in these matters in particular – wrote its own critical piece on the topic: “The chimera of private finance for development”. It cites a forthcoming study from ODI Global on blended concessional finance, which finds that, in sub-Saharan Africa, every grant or concessional dollar only attracts 59 cents of private co-financing.

This is great and perhaps overdue recognition for ODI, whose researchers have been researching, analysing and publishing on the apparent effectiveness of private finance mobilization initiatives since at least 2019, when a report found ratios of “development money” to “private finance” to be in a similarly dismal range as its forthcoming report:

Back to the Economist. The story even points out that private money is not necessarily better than nothing:

Governments get themselves into tangles when trying to assure investors of revenues. Under offtake agreements with private energy firms, Ghana has handed over hundreds of millions of dollars for power it does not use. It also loses money by selling electricity to consumers at less than it costs to buy. The problem is a general one: in countries with a lot of poor people, it is hard to run utilities profitably while also making them affordable.

This is also why attempting to make projects investable with securitization — which World Bank head Ajay Banga is still keen to do — is hardly going to lead to huge swell in privately co-funded infrastructure projects.

IMF prescriptions

The IMF’s hold on countries policy decisions and scope is hard to overstate; even countries not in IMF programs are influenced by it: many Asian countries built up unnecessarily big capital reserves as a way to avoid going back to the IMF.

But exactly how IMF requirements plays out in particular countries is rarely chronicled outside of each country’s domestic media. When the detail is laid out, it’s often staggering: Zambia was required to cut its deficit from 6% in 2022 to a 3.2% surplus in 2025.

This is from The Tricontinental’s great and shocking dossier of Kenya and Zambia’s recent IMF programs:

This drastic fiscal consolidation had two sides: expenditure reductions and tax increases. On the expenditure side, the IMF wanted the Zambian government to reduce public expenditure in the billions of dollars from 2022 to 2025. They demanded an immediate stop to new capital expenditure (on public goods such as roads and power stations) and a reduction or elimination of expenditure favourable to the poor and working class. In the latter category, the IMF wanted the government to abolish fuel and electricity subsidies, although this would lead to cost-of-living increases.43 Crucially, the IMF singled out the highly successful Farm Input Support Programme (FISP), which had been introduced in 2002 and had greatly aided Zambia’s food sovereignty by providing input support to millions of peasant farmers. The IMF required the government to reduce its funding to the FISP from 3% of GDP at the beginning of 2022 to 1% of GDP by 2025. A recent analysis has argued that this decision is largely responsible for the hunger crisis that enveloped Zambia in 2024 and continues to the present day.44

China electro-stateism

A week ago now, the FT published its daily “Big Read” on the rise of China as an electrostate.

Yet even a decade ago, China’s rate of electrification was ahead of Europe and the US. Since then, those rival economies have seen electricity as a final share of energy plateau at around 22 per cent, while electrification in China has surged to 30 per cent.

“Nobody calls it neo-Maoist or autarkic now; China was just way ahead on de-risking and resilience,” a China risk analyst says.

Chinese emissions in 2024 and early 2025

In more potentially-encouraging China news, Lauri Myllivirta found that last year, for the first time, China’s overall emissions emissions from power generation fell, even while its electricity demand grew. Previous falls in power emissions have been from slowing overall growth.

If sustained, the drop in power-sector CO2 as a result of clean-energy growth could presage the sort of structural decline in emissions anticipated in previous analysis for Carbon Brief.

The trend of falling power-sector emissions is likely to continue in 2025.

However, the outlook beyond that depends strongly on the clean energy and emissions targets set in China’s next five-year plan, due to be published next year, as well as the economic policy response to the Trump administration’s hostile trade policy.

Not all China’s energy security efforts bring about a fall in emissions. Coal-to-chemicals production grew by an estimated 16% last year. As other sources of coal demand are falling, it’s a cheap feedstock that avoids imported oil, and the industry is among Xi’s “new productive forces”.

Some things we’ve been reading:

The belligerant idealism of climate realism - Advait with an absolute banger. It’s not bipartisan, not pragmatic — and the future of clean energy is not perovskite.

What Germany’s Economy Really Needs - by Isabella Weber and Tom Krebs

Silicon Valley’s reading list reveals its political ambitions - Henry Farrell (from February; but an incredible essay on the tech sector’s canonical texts and how they are (mis)understood.)

Add a comment: