Those Wonderful Toys

I rewatched the 1989 BATMAN film over the weekend. I have seen it countless times, starting when I was child, in the theater. It’s been a film that’s always loomed large in popular culture, though it’s influence has been rapidly receding as new superhero films—and new Batman films—take over the public’s imagination. I watched AVENGERS (2012) a few days prior, and the vast gulf between the two films cannot be overstated. Whatever your opinion about the two directors may be, one thing that is undeniable is that they have very different focuses. As a director, Whedon has shown he is primarily concerned with story, while Burton has made a career on visuals. Which is why AVENGERS is an enjoyable action movie that competently juggles a large cast and a memorable villain, and BATMAN is a work of art.

It’s also about art, and being an artist, which is a wild thing for a genre known for men in spandex punching each other, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

Tim Burton was, by all accounts, not a comic fan. He loved Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s THE KILLING JOKE, though. You can see that influence in the film’s themes of obsession and depression, and the way Burton stages the Joker’s origin. But Burton, production designer Anton Furst, and cinematographer Roger Pratt were not interested in recreating the comics. Instead, they built something unique and purposeful, where every shot was artfully composed and every moment meant something. Nowhere is this more clear than in the scene mid-film in the Flugenheim art museum.

Vicki Vale (Kim Bassinger) goes to the Flugenheim art museum ostensibly for a date with Bruce Wayne (Micheal Keaton) but, unbeknownst to her, has actually been set up by the Joker (Jack Nicholson). Earlier in the movie the people talk about cash-strapped the once-great city of Gotham is, and we see that reflected in the museum set. The museum is huge, as all the buildings in Furst’s Gotham are, making the people who walk in them small and vulnerable-looking. Vikki herself is dwarfed by the gargantuan industrial vents that dominate the entrance (another hallmark of Furst’s Gotham, where every building is part of an even larger machine). The art in this vast space is sparse and indifferently collected. An ancient Egyptian bust is displayed with a Degas painting. No theme or commonality appears to be on display. Instead, the whole group feels like the remains of several larger exhibits, that were then sold off, piece by piece, until this is that’s left in a museum too big for the scarce amount it contains. Not that it matters, because there’s barely anyone looking at the art. Most of the people here are at the museum’s restaurant, where Vicki is shown to a table.

Time is nebulous in BATMAN. Much the same way the art in the Flugenheim spans several eras at once, Gothamites walk around in 1940s and 1980s fashion, watch newscasts filmed with 1960s televesion cameras, while gangsters use tommy guns, modern machine guns, and most inexplicably, swords. It’s always night except when it’s blindingly day. Batman is presumably early in his career as a vigilante at the start of the film, still an urban legend to petty crooks. But both Bruce and Alfred have a long-campaign weariness about them, as if this war on crime has been going on for decades. So, too, is it unclear how long Vikki is left to wait in the museum’s restaurant. We only know that she’s been there awhile, and she’s irritated about it.

Vicki receives a air filter mask from an unknown admirer—but we know it’s the Joker, for who else writes a flirty card with crayon—and puts it on just as those giant industrial vents we saw at the beginning of the scene start leaking acid-green toxic gas. Everyone in the museum except Vicki dies, punishment for enjoying the food in the Flugenheim, rather than the art. The Joker enters, goons in tow, and proceeds to “improve” the art to a fantastic diegetic Prince song. At one moment, the Joker mimics a Degas ballerina sculpture, mockingly pantomiming a flying position while standing on one leg. It’s a clever touch of foreshadowing—he’ll be in similar position at the end of the movie, as a batwinged gargoyle brings that leg down from a helicopter, the Joker’s arms once again flapping to no avail.

Vicki is an artist—a photographer—and she brings her portfolio to the museum. The Joker positions himself as an artist, but it’s a lie to flatter himself. His main mediums appear to be collage and, well, murder. He doesn’t create, he destroys and calls it creation. He’s disfigured his model girlfriend’s face with acid, and tries to do the same to Vicki. He decides what is beautiful and what needs “improving.” Far from being an artist, the Joker is, in fact, the artist’s worst enemy: the critic.

The only art the Joker keeps his goons from defacing is Francis Bacon’s painting Figure with Meat, a painting who’s central figure is staring out in horror at the viewer. Before his transformation, Jack Napier chafed at not being recognized, not being seen. Now as the Joker, the only art he likes is the art that looks back, that puts the attention back on him.

But what of Batman? Bruce is presented as not an artist, but he is a appreciator of fine art. An earlier scene at Wayne Manor showcases not only that Wayne has a larger art collection than the Flugenheim, but that he’s knowledgeable, already knowing about Vicki’s work before he meets her. Bruce, it turns out, is a more dedicated artist than anyone imagines. Bruce dons a new sculptured face and body and crashes through the skylight (classic move) into the museum. He is an artist who has turned himself into an artwork, who has wrapped his black cloak of misery around himself and turned it into an armor. Wearing his depression on his sleeve, Batman cannot be harmed by the Joker or his criticisms. Batman enters literally above the Joker, and when he lands it is only to take to the air again, Vicki in his arms, suspended by a Bat-rope.

The Joker’s envy of Batman reaches his peak in the museum, as he beholds a man who has transformed himself into a walking work of art. The Joker is rendered uncharacteristically silent by Batman’s appearance, only spitting out a jealous “Where does he get those wonderful toys?” as Batman swings out of the museum and on to the street. The unspoken answer is that he made them, just as they in turn make him. Those wonderful toys define Batman, the art defining the artist.

In Tim Burton’s BATMAN, the artist is the hero, having made himself one with his art. His greatest villain is a critic, his greatest love a fellow artist, and his father figure indulgent but ultimately does not understand what this whole art thing is about. Every frame is lovingly composed and shot, the light perfect, the sets heavy and physical. In order to make a Batman movie, Burton had to make Batman into a character he understood, a man weighed down by obsession and depression, but nonetheless uses his skills to fly. Preferably in a plane shaped like a bat.

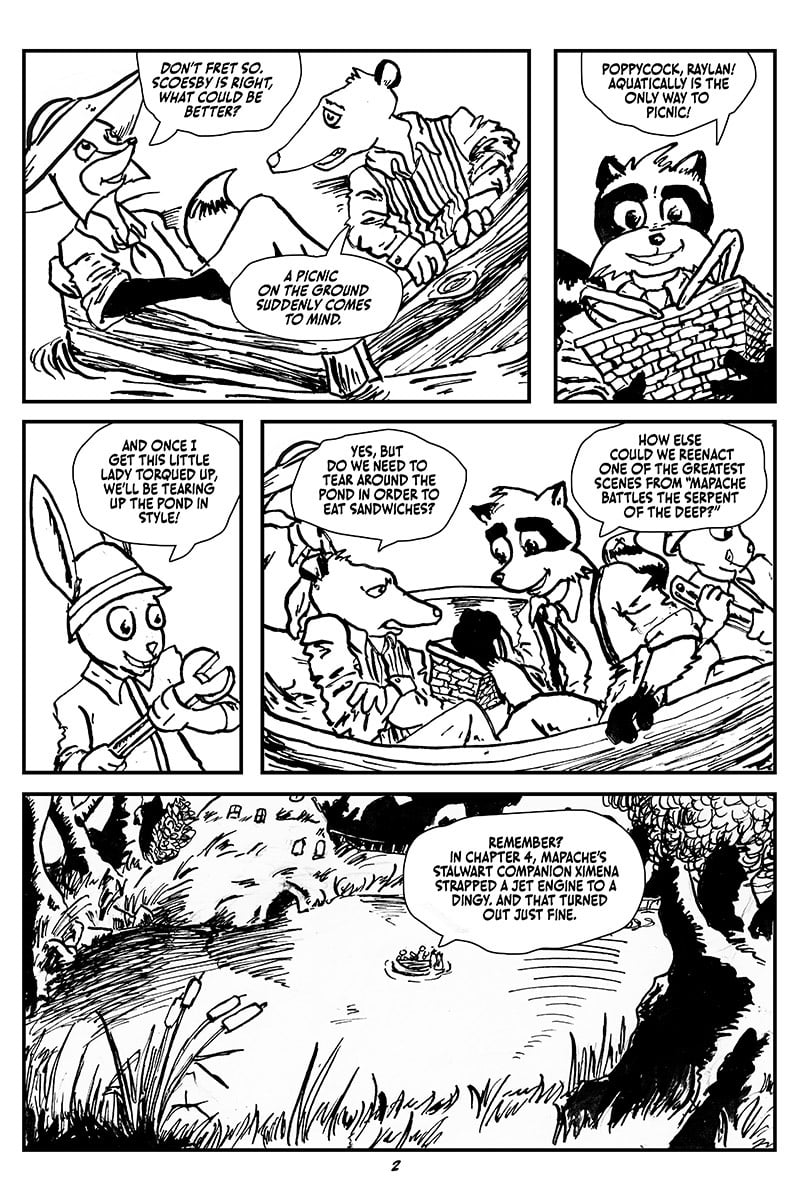

Moving on to something lighter, here’s page 2 of Scoesby Cuts A Rug, which I wrote and drew. It explains why our motley crew are in a boat with a giant engine attached. Page 3 is already on the Patreon, if you wanted to see it there.