I Don't Want To Hear About The Book Of Veles Anymore

What does the Book of Veles teach us about the dangers of AI? Less than some people keep wishing it would.

Every alarmist photography take about AI at present makes one (or sometimes more) of three basic arguments:

We're all ****ed because these machines infringe on copyright

We're all ****ed because nobody will need photographers anymore

We're all ****ed because no-one will believe our images any more.

There are varying degrees of problems with all of these arguments, but today we're talking about the third one.

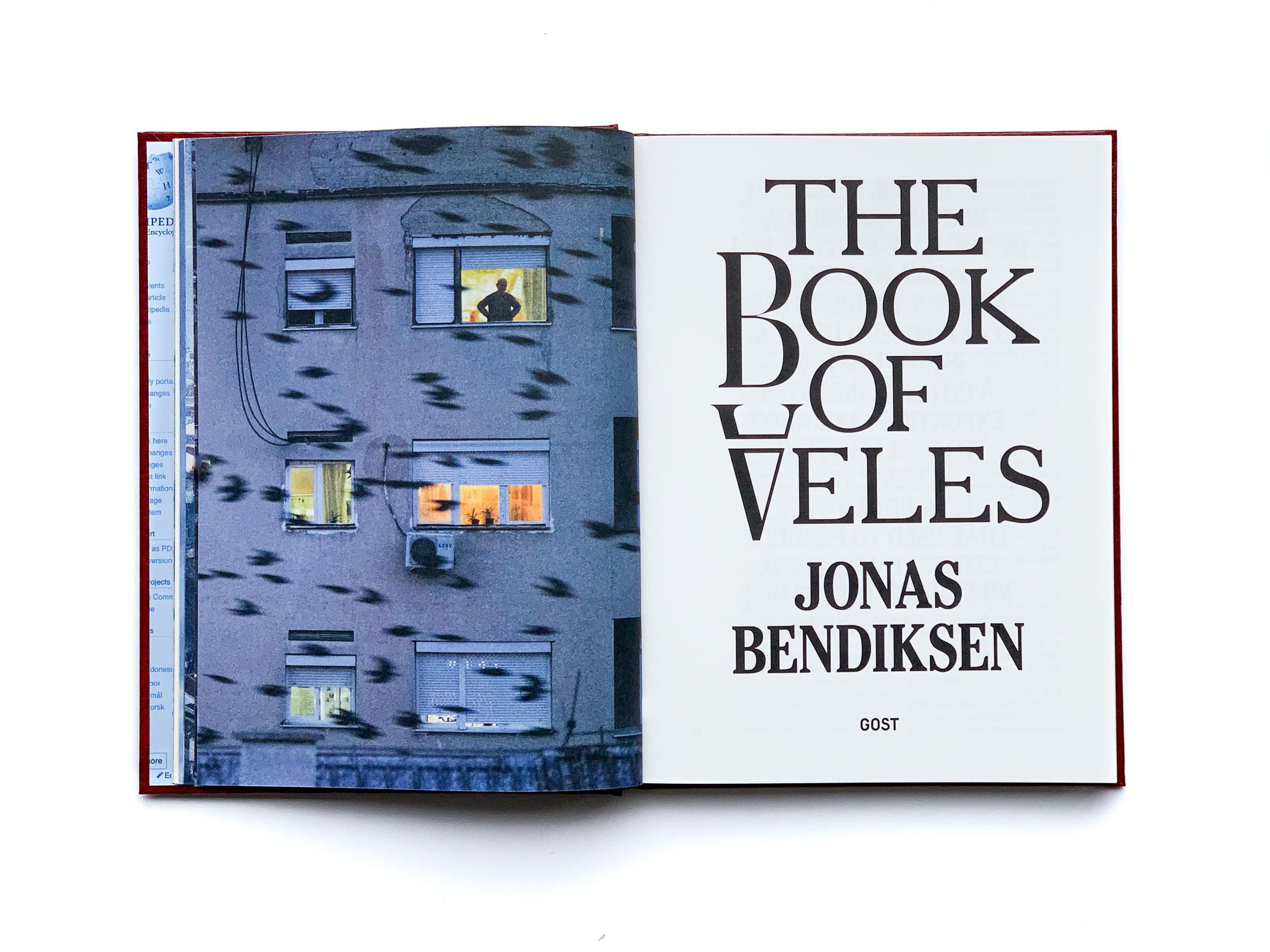

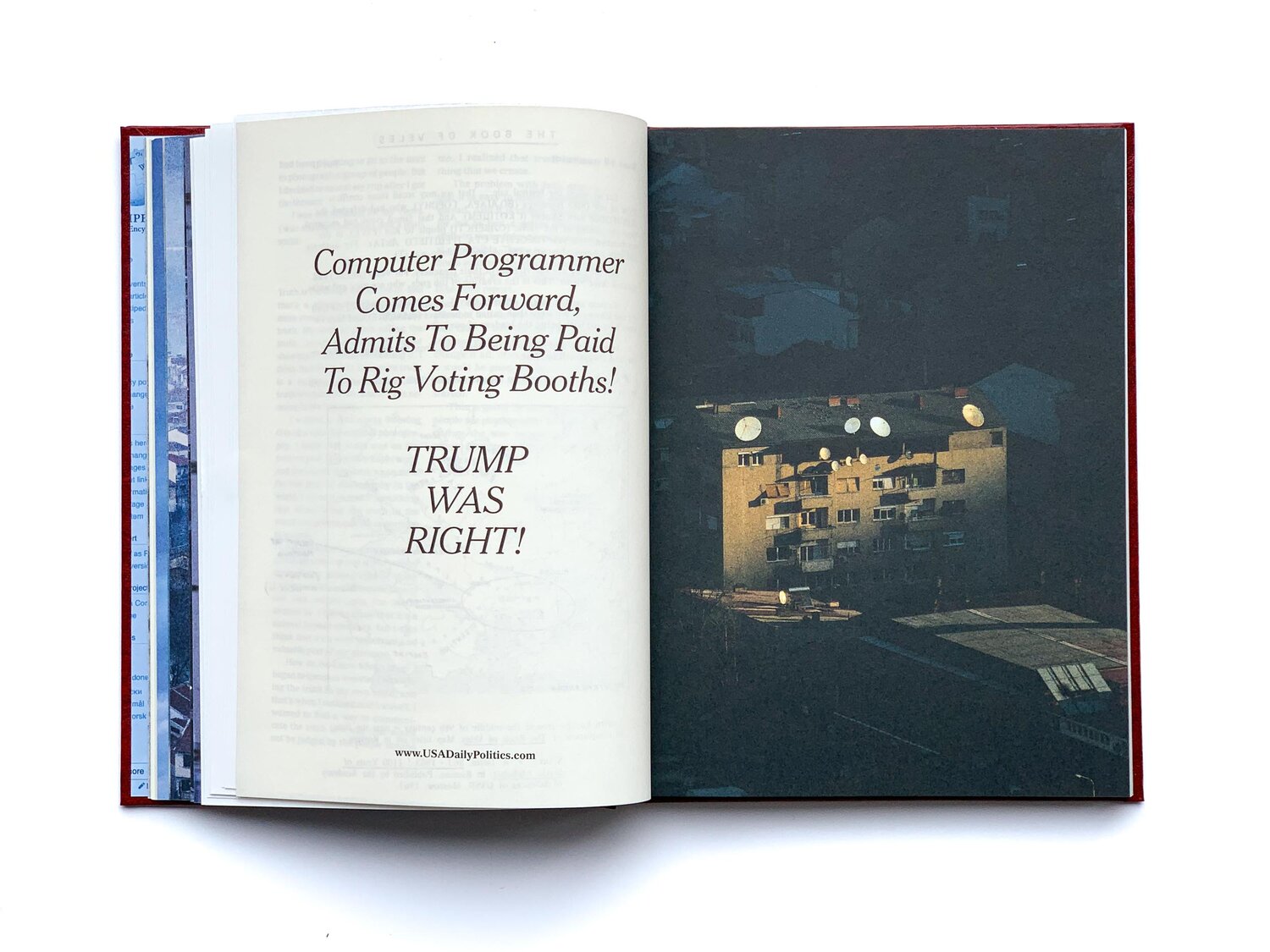

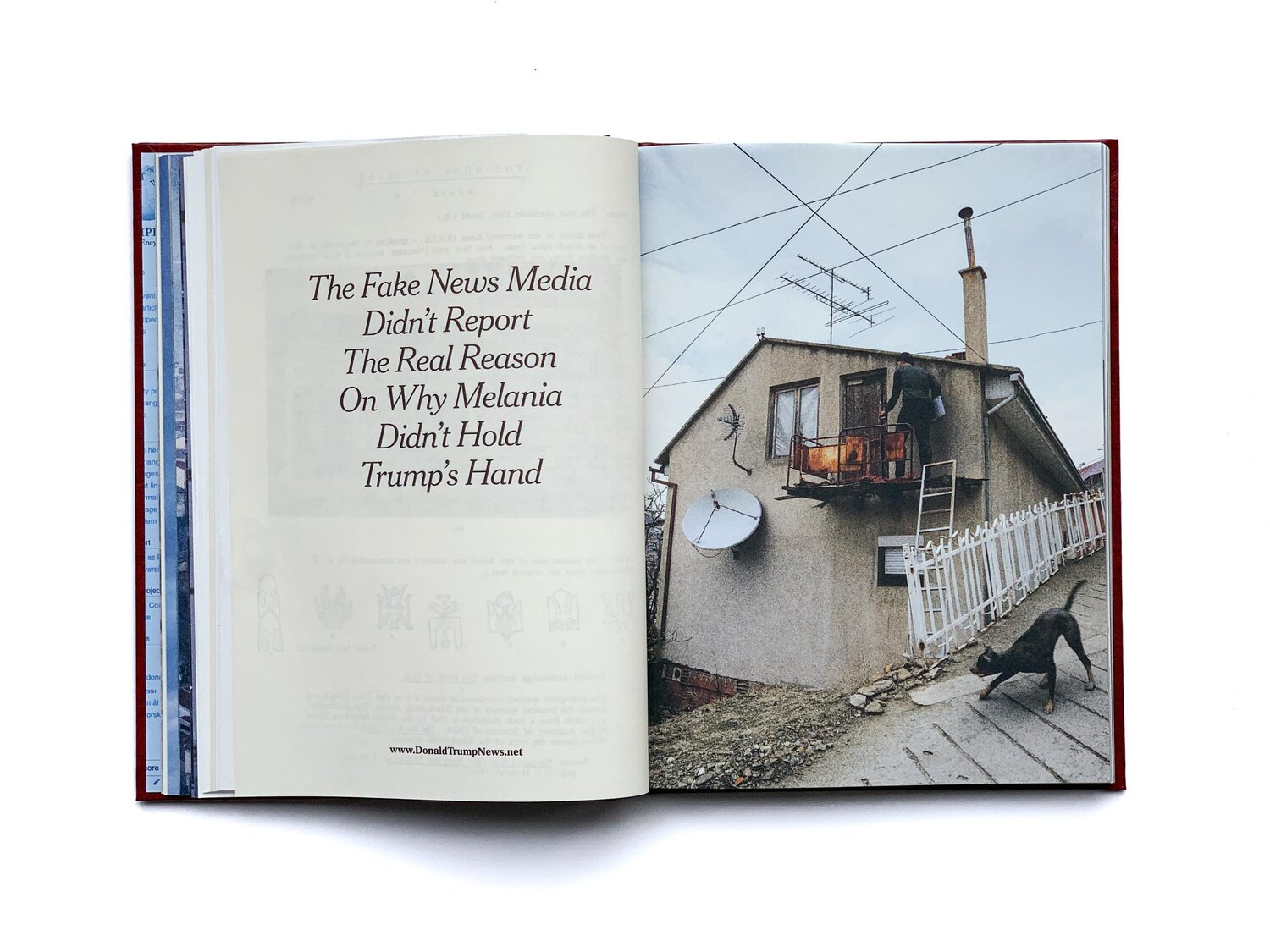

The project underlying The Book of Veles is simple yet visionary. Jonas Bendiksen spent the first COVID lockdown in a basement, layering computer-generated imagery into real photographs of the town of Veles, Northern Macedonia, and added AI-scripted captions to create a bewildering (false) story about a town's role at the heart of the fake news industry. He then intertwined the results with pages from a forged 19th-century (?) manuscript called The Book of Veles, before circulating it as a 'real' documentary project. He remained largely silent as the deception claimed scalp after scalp, culminating in a prestigious screening at Visa Pour L'Image in Perpignan, the Crufts of photojournalism.

As time passed and it became clear that nobody had thought to question the work, Bendiksen started making sock-puppet social media accounts to accuse himself of lying. In the end it was Benjamin Chesterton (the closest thing photography has to a conscience) who spotted a detail amiss, a matching outfit between an avatar and a figure in an image, and from there the whole story came out. The reason this book is at the top of my mind right now is because many prominent denizens of Photoland have made reference to it recently in talks about the future of photography in the age of generative imagery.

Exemplary of this is Joumana El Zein Khoury's remarks during an excellent recent evening about generative imagery at Pakhuis De Zwijger in Amsterdam. In a fairly predictable Magnum-sponsored rote grumbling about AI's threat to photographic truth, Khoury cited The Book of Veles as proof that falsified images can and will fool everybody, and that by doing so they will create and propagate false narratives. She's right, of course. The reason why the initial deception of The Book of Veles was so successful, and the reason it took so long before it was uncovered (by a man hated in Photoland), is because it showed viewers what they expected to see.

In his Galaxy Brain column for the Atlantic, Charlie Warzel wrote this about the recent 'Pope Coat' images:

Pope Francis’s rad parka fooled savvy viewers because it depicted what would have been a low-stakes news event—the type of tabloid-y non-news story that, were it real, would ultimately get aggregated by popular social-media accounts, then by gossipy news outlets, before maybe going viral.

Veles manages to pull a different rabbit out of the same hat - it was so successful because the real topic was its audience. It relied on being taken at face value and on the correct assumption that its viewers would consume and move on. The project raised no eyebrows because it proved the thing that every cable news anchor had been saying- there was an enemy; living in a grimy, foreign twilight where greed and desperation are the order of the day. That is the story that many wanted to believe about Trump, after all; that his votes were the result of deception, not a symptom of a growing disenchantment with neoliberalism. The images Bendiksen had brought back from his adventuring were just as promised, and audiences were satisfied and felt no need to enquire further. Their suspicions were confirmed, and anyway, it must be true- he's in Magnum.

While it was certainly far ahead of its time in exploring the power of manipulated images, it's wrong (in my opinion) to present The Book of Veles as a warning about AI. It's a book about the vulnerability of truth, but not about how we can be fooled by falsified images so much as how easy it is to lie to an audience when you're speaking from a position of power and confirming their beliefs. Images have both a maker and a viewer, and each brings something to the encounter. An image can only easily fool its viewer if the viewer finds its contents to be consistent with what they have seen or heard elsewhere. Veles does not teach us about the threat of deceptive imagery so much as it asks its audiences why they trust what they're looking at. It's a reflection of the chequered history of photography that the Global North is only now catching up to the rest of the world in learning that it's not enough to assume that images are truthful just because they are published by powerful organisations. Using Veles as an example of fake news absolves its dupes of the sin of credulity, and allows them to sidestep an urgent discussion about the dangers of mindless looking.