History Will Complete The Puzzle

An interview with Wai Hang Siu, the artist behind 'Clean Action Hong Kong', an artistic intervention addressing questions of representation, surveillance and protest

DP: Could you explain how “Clean Hong Kong Action” came to life? Where and when were the images made?

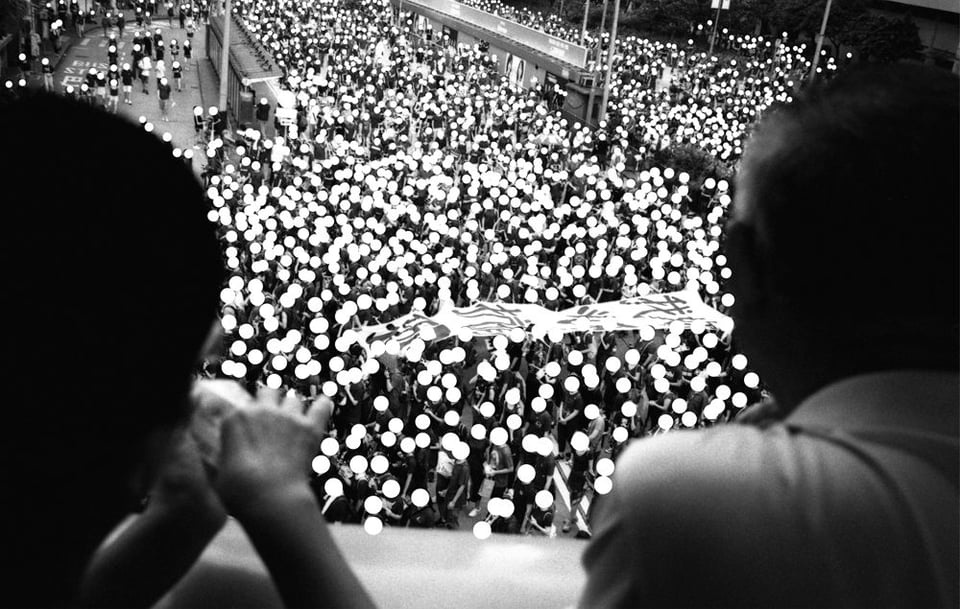

SWH: I made this series in Hong Kong during 2019-2021. The original images (without holes) were taken in 2019 while the most prominent and most prolonged protests were happening in Hong Kong. I initially hadn't intended to make art or do documentaries during that time but just to use my compact film camera as an instrument to record my experience in that BIG HISTORY.

However, when the protest kept going, things changed quickly. People began to cover their faces with marks or umbrellas. They refused to be photographed and showed hostility to the camera. That hadn't happened before, and it meant that I found it very hard to pick up my camera. And when I reviewed the processed film, I thought my photography was helpless and somehow a threat to them. So I tried to find a way to bring back my photography and to respond to this frustration. In the end–removing people's faces was the only powerful means I could think of at that time, and so I started to punch out all faces in the series of Clean Hong Kong Action.

DP: Can you describe the process of removing people's faces from the images? The physical act (or perhaps digital) but also your emotional reaction to it?

SWH: I produced one original image, photographed in Admiralty, in my old studio in Hong Kong. When I looked into it, thousands of faces looked back, reminding me of the fear people faced and their mistrust toward each other. In response to that thought I started looking for a way to hide their identity and to reveal the structural and physical violence present in the space but not visible. So I picked up a leather hole-puncher and tried to remove the faces on the print. This action neutralised the image and redeemed it from anxiety.

For me, this series isn't only about the image but also about the physical action it provoked in me, and its representation of the atmosphere of fear and violence at that particular time.

DP: The role of the photographer is dangerous because the documents we create can be read by anybody. In what ways do you think the internet is affecting the purposes, processes and meanings of protest photography?

SWH: The image itself is neutral, but the medium displaying the image is what contextualises the photography. For instance, when you read the newspapers of 2019 in Hong Kong, you will find that almost every newspaper had similar pictures, no matter which side they were on. What's different is the topics and texts on it. Then you, the reader, would fall into the context created and understand the image based on your preexisting subconscious preference. This is true for all kinds of photography, not only in the documentary aspect.

The author is dead, and we are in the post-truth era. As photographers, we should accept that no absolute truth exists in the world, but instead we should at least believe that our photography can reveal part of reality and employ it ethically. History will complete the puzzle. The more photographs we have, the closer we will be to an absolute truth.

DP: What role(s) can photography and photojournalism play in the age of computerised mass surveillance?

SWH: We are individuals and as such we have no power to get rid of surveillance. The people in power are trying to build their own picture of ideology, history and authority. At the same time, fortunately, photography is accessible for everyone. People can understand the world better through its depiction across multiple images than from a single point of view.

Nowadays, photography and photojournalism play a vital role in confronting the mainstream discourse, giving us more pieces of the puzzle to understand the world.

DP: Why do you feel that the "re-establishing" of photography of these sorts of events is so important?

SWH: I wasn't a photojournalist in 2019, but an ordinary protester and a man who likes to use a camera to reflect my concerns. I encountered difficulties in the gap between photographing and being photographed. This is a problem of trust, and it is not only about trust between the photographer and the one captured but also about trust in the legal system. What I mean by the "re-establishing" of photography is about the rebuilding of freedom of speech and expression, especially in a totalitarian state.

But it is extremely hard for photographers and citizens to protect or expand these sorts of establishments alone. What we can do, though, is to find a more innovative way to express ourselves within this limited freedom. In my case, that was the act of removing all of the faces in my photographs.

Interview conducted by Anna Kućma

Wai Hang Siu engages with society and photography through the photographic medium itself. Local history threads Siu’s practice and is the vessel through which he uncovers the values of Hong Kong. He is interested in depicting landscapes and objects as they connect people with collective memories. In his take on the potential of photography, Siu highlights the encounter between traditional photography and contemporary digital work.

Siu was the recipient of the First Price of Hong Kong Photobook Dummy Award 2021, the Hong Kong Human Rights Art Prize (2018) and the WYNG Masters Award (2014 and 2016). He was also named ifva Emerging Talent in 2016. His works were collected by The New York Public Library(US), M+ Museum(HK) and private collectors around the world, and had exhibited in The United Kingdom, New York, Germany, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and mainland China.