A Piffany about Getting Into College

College admissions do not happen in a vacuum. Nor does each individual applicant’s journey.

Thirty years ago this week, a slender envelope began to make its way from Princeton, NJ, to my family’s mailbox in Simsbury, Conn.

Opening it, the first word from the Dean of Admissions, Fred Hargadon, told me everything I needed to know: “YES!”

My dream had come true.

Which I had to wonder about until the end, having applied for early action and getting deferred that December, then receiving notifications from all of my so-called safety schools before ever hearing another word. I would enroll in Princeton University. I’d made the Ivy League. As a high-school senior, I ranked fifth in my class of 86. The students ranked fourth and sixth both received rejection letters from Dean Fred and Princeton. So. What happened? What made me so special?

At a dinner that May, one of the school’s Board of Trustees congratulated me and specifically mentioned my college essay. So there’s that.

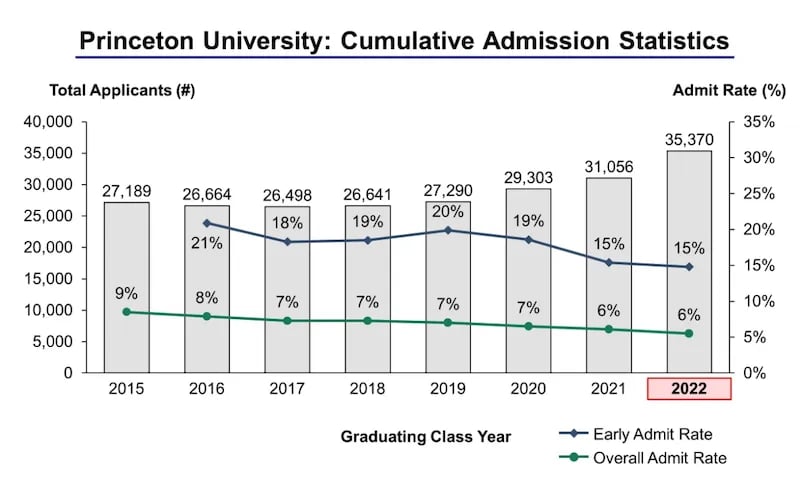

Objectively, I’d scored the highest in my class on the SAT. That wouldn’t have set me apart from the more than 12,000 applications vying for about 1,100 spots at Princeton (according to stats provided in 1988 to the New York Times, the average incoming student SAT scores for the class before me were 647 verbal, 696 math; mine? 600 and 760). If those application numbers sound outrageous now, you’d be right only about it being even more outrageous now — last year, Princeton admissions reported these stats for the Class of 2022:

Total Applicants: 35,370

Total Admits: 1,941

Total Enrolled: 1,346

Admit Rate: 5.5 percent

I also served as editor-in-chief of the school newspaper. Again, not that unique for an Ivy League applicant.

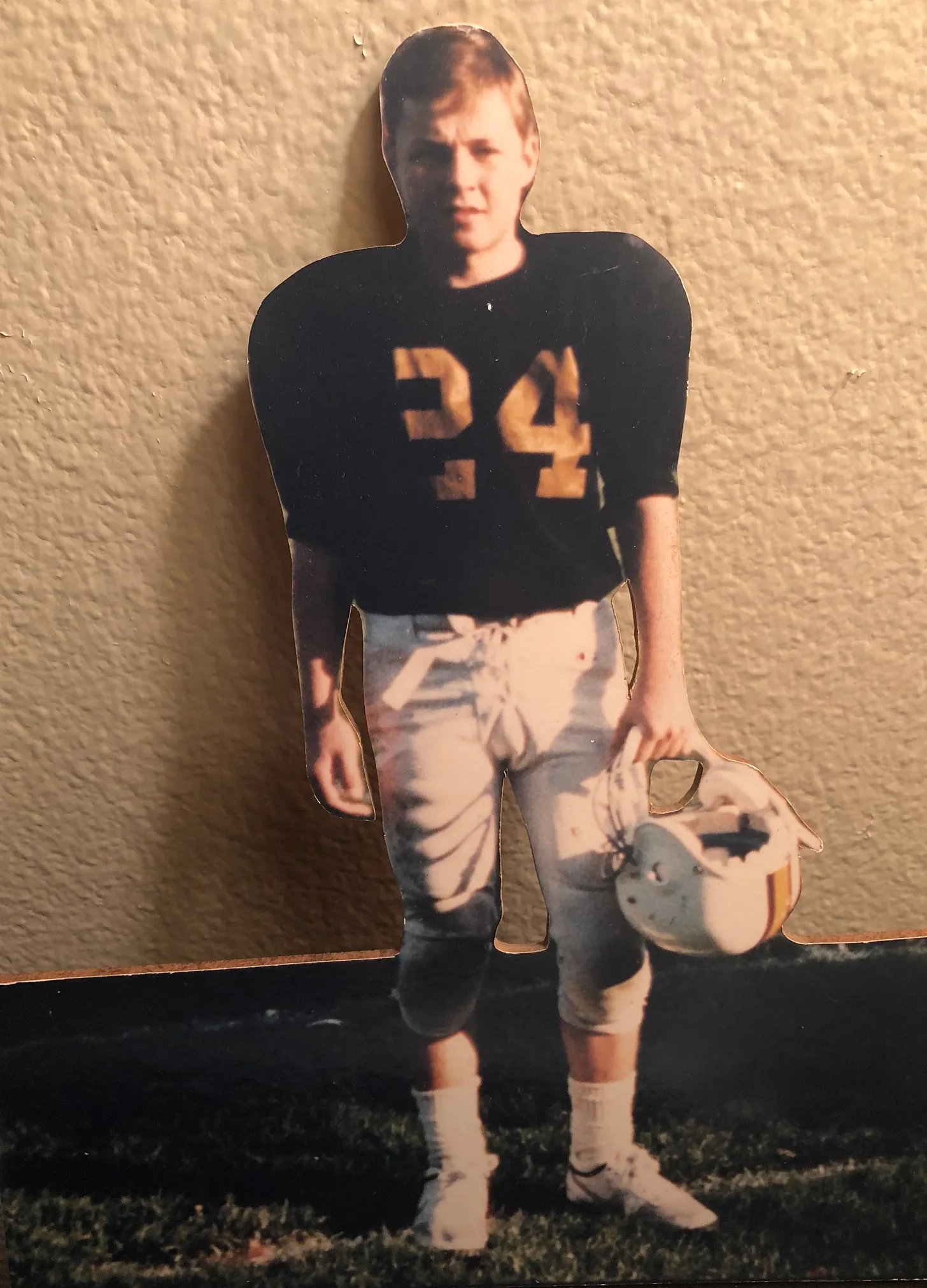

Here’s something that turned out to be special, though: I ran a 4.6 40. As it turns out, that time may not have been the most accurate (hand-timing is notoriously slower on the gun than electronic timing, which means so many high-schoolers claim even faster times these days). But as a starting varsity football player, who weighed 130 pounds soaking wet and wearing my pads, I was quite an anomaly. And Princeton just happened to be one of a handful of Division I colleges fielding a varsity Lightweight Football Team (the maximum weight at weigh-ins 48 hours before games was 148 when I played; it’s higher now, and in fact, Princeton recently scrapped its program because the team became so futile after I left (SUPER FUN FACT!)). In 1989, the Eastern Lightweight Football League included Army, Navy, Penn, Cornell, Rutgers and Princeton. Army fielded 100 strong, and dominated the league. Almost as if they had something special going on over there at West Point. Princeton’s lightweight football alums also count the former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. And the actor Mark Feuerstein, my classmate.

I stopped playing college ball after my sophomore year, although I continued competing in sports on campus, earning the Intramural Player of the Year Award my senior year. That’s almost as good as Valedictorian, right, Mom and Dad? I also learned later that, as a varsity sport, the lightweight football coach got to submit a list to Admissions of folks to take a second look at, and that I may have made that list.

So there.

Princeton still, currently sending out acceptance letters in 2019 for the class of 2023, has provided guidelines for high-schoolers with special skills in the arts and athletics. The admissions department suggests aspiring architects, writers, dancers, musicians, actors and artists to submit additional materials on their behalf. From the guidelines for athletes: “Talented student athletes interested in one of our varsity Division I programs should contact our coaches for more information about varsity athletics at Princeton. Coaches will advise the admission staff about applicants with exceptional athletic talents.” I actually did fill out a sheet when I applied for Early Action indicating my interest in football.

The year ahead of me in high school, only one student made it into Princeton, and he was the hockey goalie (who introduced me to Lyle Menendez, which is another story for another time). A girl two years behind me in high school played on Princeton’s 1994 NCAA Champion lacrosse team.

BUT.

LET US BACK UP A FEW STEPS IN THE PROCESS.

Did you read that I claimed to start at running back on my high-school football team? Did you see what I looked like then? That all became possible, in part, thanks to our coach installing the run-and-shoot offense our junior year (we went winless that fall, ugh). But things turned around senior year. And the run-and-shoot offered not one, not two, but three spots in the backfield. I played left wing back, which often put me in motion before the snap behind the fullback. Or on quick outs to the flat for a reception.

BUT.

Nobody, not then, and not now, would ever have expected or believed me to be a professional football player, let alone any football player. I hadn’t cracked five feet tall and barely touched triple-digits on the scale when I first matriculated high school in September 1985. But I didn’t go to public high school. I went to Westminster, a prep school, as a day student in my town, actually walking distance from my home. And Westminster mandated all students participate in athletics in each of the three trimesters. Fall offered soccer, cross country or football. And soccer had four teams, allowing room for just about all of the boys who weren’t string bean runners or muscle men-to-be. But I looked straight in the eyes of my new faculty adviser, Mr. Jackson. Mr. Michael Jackson. No relation. And told him I wanted to play football. He was one of the two head coaches for the second-level Football team (which they actually called Thirds, because face it, calling us JV would give this outfit too much credit). So he smiled and said alrighty then. I didn’t play much either of my first two years, that I can even recall.

But each summer, I ran and ran and ran the streets of my hometown. And I hit the gym with my “best” friend, who played soccer, squash and tennis, became President of the Student Body, went to Harvard for undergrad, Stanford for grad school and might run the world as part of the not-so-secret cabal that remains so thanks to the decoy of the “deep state.” For all I know. I got lean. And I got fast. Quicker than you’re thinking. Certainly quicker than Coach Eckerson expected, and so he kept me on the First team my junior year. I surprised everyone by learning how to outrun everyone who tried to chase me down. That skill, I actually had many years of experience. Thank you, bullies.

My bullies inadvertently taught me how to juke someone out of his cleats.

WHICH.

ACTUALLY.

BUT NOT REALLY.

Also helps explain how I ended up in prep school to begin with. I was the shortest kid in my elementary school. I’m including all of the grades here. A fourth-grader tried to bully me when I was in sixth-grade. I was having none of that.

But I also was perhaps the smartest kid in elementary school (at least according to IQ scores our teacher inadvertently left out on his desk), and one of a handful of the smartest in junior-high, which meant I got to skip “reading” class for the gifted program (which our town called DAP, for Divergent Activities Program). The rest of my days were spent in utter boredom in classes with 20-30 other kids, daydreaming of after-school band (first clarinet!), computers and anything that would take me away from there. In the best public-school system in Connecticut, I could get As in my sleep. And at 13, I actually wanted more.

I certainly wanted the attention, if not also the challenge. I soon found it my freshman year (third-form) in English class with Mr. Gordon McKinley. He taught me that “context determines meaning,” and gave me my first C for a trimester and my first and only F on a paper. I was beside myself. But he made me a better writer and a stronger thinker. He helped spark the fire in me that turned me into a professional journalist.

Without him, who knows where I would have ended up.

Certainly not Princeton.

Or maybe I could have, but it wouldn’t have been the way I did it.

BUT.

I couldn’t have gone to prep school if my parents weren’t successful enough in the 1980s to consider paying for it. It was what, $6,000 a year then for a day student? Now, it’s crazy expensive. Crazy. Expensive. But back then, it felt crazy expensive, too. But because I was and still am an only child, there wasn’t another mouth to feed, clothe and school. My parents could invest their entire future in me.

So it’s not just one thing that got me into Princeton. But rather, a whole Butterfly Effect of decisions over years, going back to my parents deciding not to have more children, raising a smart but lonely kid who yearned for adventure, found one a couple of miles away that prompted me to embark on new experiences, which completely transformed me from a computer geek into an athlete and a journalist.

I wasn’t thinking any of that in eighth grade.

I was just bored.

But when we talk about the college admissions process, it’s so easy to look at in terms of black and white (or race in general), or statistics. We forget how many very human decisions went into it first.

That’s also true about the college admissions department, too.

They’re facing all sorts of privileges (race, money, status) and structural biases (race, money, status and the status quo).

Hargadon was struck in his first year by how different Princeton was from Stanford from the viewpoint of an admissions dean. Stanford had roughly 1,600 places to fill, compared to no more than 1,150 at Princeton. At the same time, the pressures to admit students from important constituencies — whether alumni children, athletes, minorities, engineers, or potential scholars — were similar at the two institutions. What this meant in practice was that a high proportion of the class at Princeton was filled with members of politically powerful constituencies even though “unaffiliated candidates” (as Hargadon called them) constituted the largest segment of the applicant pool. As a consequence, admissions at Princeton had a more intensely zero-sum character than at Stanford, and the power of organized constituencies effectively limited the latitude of the dean of admission.

A savvy administrator, Hargadon quickly realized that he would have to enlarge his zone of discretion if he was to place his own imprint on the Princeton student body…

He ensured that he and his top advisers got final say on every applicant, put distance between themselves and the “Alumni Schools Committees” that had applicants interviewed in their home states/regions by alums, and expanded the ratings category (each applicant received a 1, 2 or 3 in academics and non-academics) so Princeton couldn’t possibly admit all of the 1s.

“Dean Fred” retired in 2003, and died in 2014. A dorm is named for him now on campus.

A lot has changed in 30 years, of course. The price of a college education has skyrocketed, while the benefits of one have come under increased scrutiny. That’s not stopping hundreds of thousands of children and their parents from attempting to game the system in any way that they can. Status and privilege remains an irresistible allure for so many.

I remember that feeling. I also remember that moment, moving into my freshman dorm, meeting my roommates, when imposter syndrome first surface. Did I belong in Princeton? Then I attended my first week of classes, looked around, and wondered: How did some of these other kids get in here?

That remains the big question.

POSTSCRIPT (April 9, 2019): From Princeton University’s Office of Communications, some very related news: “Karen Richardson, a leader in college admissions and a Princeton graduate and native of New Jersey who was among the first generation in her family to attend college, has been named dean of admission at Princeton University. She will start in her new role on July 1.” That’s Karen Richardson, class of 1993, classmate of mine. Congrats, Karen!