Will 2020 finally end next year?

In my memory, 2020 and 2021 have merged into one hazy blur—a pandemic, chaos in the world, and lots of quiet nights at home. The holidays have all blurred together, too—2021 Christmas is indistinguishable from 2020 Christmas, I have to think hard to separate my memories of 2021 Halloween from 2020 Halloween, and so on.

And I suspect that 2022 is about to fall into that same misty space and melt together with the two previous years. When all is said and done, I’ll forever recall three years of my life as having one single summer, a single winter, a single fall.

This feels unsustainable. I can’t imagine that 2023 will join the fog of the past three years. I expect that I will get out more in 2023, and will have more experiences to make the year distinctive from the past three. But maybe that just represents a failure of my imagination—maybe this monoyear is just a product of getting older, and it’s what my older relatives were trying to explain to me when they described the hastening of years that occurs with age.

In any case, this might sound like a complaint but it’s really not—I’ve been lucky enough to have stable housing, continuous employment, and a very enjoyable social life during the three most tumultuous years in recent history. But becoming aware of the monoyear definitely feels like a first tentative step outside of the monoyear. You can only live in the darkness of March 2020 for so long, after all. Right?

I’ve been writing

I wrote about three of my favorite reading experiences of 2022 for the Seattle Times. If you’re desperate for a great book, I advise you to click through to this one—there are some great book recommendations, both Seattle-centric and not, from Times critics like Moira MacDonald.

Also for the Times, I wrote about Magus Books, which is the quintessential Seattle used bookshop. There’s something ineffable about Magus Books, and I was very intimidated to profile the shop just because that majesty is so hard to document in print. Happily, I spent a good portion of the piece focusing instead on the Magus Books Annex, a new used bookshop that just opened in the old Open Books space in Wallingford. (Fun fact: Before Magus Books was founded in the 1970s, the space was home to an anarchist bookshop called, delightfully, The Id. If anyone has any information about that shop, I’d love to hear it—very little documentation of The Id exists online.)

For Insider, I wrote about Professor Scott Galloway’s latest book and his appearance on the Pitchfork Economics podcast. Galloway has developed a reputation as a bomb-thrower on the Pivot podcast with Kara Swisher, and I don’t agree with everything he says. (He’s ridiculously wealthy, for instance, and I think his thoughts on taxation are way too conservative because he’s more interested in staying ridiculously wealthy than he is in solving some of society’s biggest problems.) But I agree with the thesis of Galloway’s new book, Adrift, which argues that growing inequality is unmooring America from the economic foundations that built the middle class.

I’ve been reading

I read the first installments in two long-running mystery series this month: One for the Money, the charming first novel in Janet Evanovich’s Stephanie Plum series; and The Deep Blue Good-By, which is the introduction to John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee character. I had more fun with the Evanovich novel—Plum’s introduction to the world of bounty hunting is breezy and cheeky—but MacDonald’s book stunned me with its great writing and sheer literary quality. I can see why the Travis McGee novels are a favorite of wildly popular writers like Stephen King—they combine pop sensibilities with serious writing craft in a way that elevates the mass-market mystery format.

Another pair of books accidentally aligned themselves in my reading life this month: As a young man, I idolized both Haruki Murakami and Quentin Tarantino, and they both released autobiographical books this fall. I enjoyed Cinema Speculation, Tarantino’s account of his informal education from the great films of the 1970s, but it did feel a little tiresome—like the charming dinner guest who repeats a handful of stories a little too often. Murakami’s latest novels have failed to emotionally move me, and his latest non-fiction release, Novelist as a Vocation, has inspired me to actively dislike the man. Murakami devotes a whole chapter to explaining how little he cares about literary awards, and he demonstrates his lack of concern by writing at length about an award that he has never won and which he definitely never thinks about on a daily basis. Tarantino often lacks humility, but Murakami now feels hopelessly high on his own supply.

One of the readers of this newsletter suggested that I read Oregon sci-fi novelist Kate Wilhelm’s The Clewiston Test, but for the life of me I can’t seem to locate the name of the person who recommended it. Thank you, whoever you are! The novel, about a married pair of scientists whose research takes on a new importance when the wife is badly injured in an accident, feels dated and sexist and homophobic in the way that many 1970s novels do. But I’d never read Wilhelm before and now I’m enthralled by her ability to craft a taut psychological thriller. I look forward to learning more about her life and work.

I ended the year with a fantastic book: Brian Jay Jones’s Jim Henson: The Biography. I believe that Henson was a generational talent, but at the same time I acknowledge that he must have been a challenging human being to love. Jones recognizes Henson’s faults, but he doesn’t dwell on them. Instead, he tries to pack all of Henson’s unbelievable achievements into a brisk 500 pages while also contextualizing his impact on culture, the technology of puppeteering, and his growing entertainment empire. This book accomplished everything I wanted it to—it made me feel closer to Henson’s warmth and genius without reducing itself to empty hagiography.

My favorite movies and TV shows of 2022

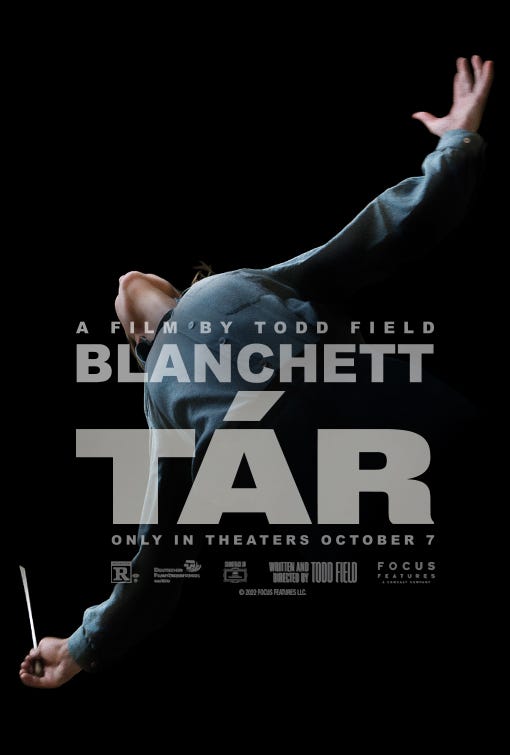

There were lots of interesting movies this year, but only two movies knocked me flat on my ass: I was happily blown away by Everything Everywhere All at Once at the beginning of this year, and I was overwhelmed by Tár at the end of this year. Both of these are movies that I will watch and watch again for very different reasons—EEAaO made me feel great about the world, and Tár was more about encroaching paranoia and darkness. But in both films, the sheer film-making on display is breathtaking.

Tár, for what it’s worth, also has my favorite movie poster of the past few years:

While those two movies are way up at the top of my yearly pantheon, lots of other movies kept me entertained. I believe I like Glass Onion even more than Knives Out, because its thesis statement is so timely it could have been ripped from the headlines of this morning’s paper. The Banshess of Inisherin was enthralling, though I felt that it had a bit of a problem coming to a graceful conclusion. Catherine Called Birdy impressed me with its charming young protagonist, and Three Thousand Years of Longing wrapped me in a warm blanket of romance and magic. Emily the Criminal was a nasty little crime story, but a great showcase for Aubrey Plaza.

For TV, I loved the second seasons of The White Lotus and Reservation Dogs. Better Call Saul somehow constructed a great and satisfying conclusion not just for the series but for the Breaking Bad universe as a whole. I thought Apple TV’s Bad Sisters was probably the best debut series I watched all year—a funny and weirdly cozy story about family and murder and murdering your family. And Amanda Seyfried’s performance as Elizabeth Holmes in The Dropout was so brilliant that it single-handedly elevated a so-so miniseries into high art.

For someone who hates year-end lists, I have to admit that I’ve grown to enjoy compiling these little reminiscences of art that moved me over the past year. If you uncovered any hidden gems or were unexpectedly moved by some art this year, I hope you’ll let me know. And I hope your 2023 builds upon your successes and excitements of the last few years while somehow being a completely distinct experience. It’s time to make room for the new.

Happy New Year,

Paul