The Hole in My Bumbershoot

Hi!

Seattle’s Labor-Day-weekend music and arts festival, Bumbershoot, announced their arts programming earlier this month. There’s a fashion exhibit, an animation show, performance art, kinetic sculptures, a “comedy dome,” a cat circus, wrestling, gymnastics, skateboarding, and more.

You know what they didn’t announce? A single damn literary event of any kind.

This is a tremendous bummer. Bumbershoot has always celebrated literary arts. Jim Carroll headlined the festival’s arts programming in 2000. They’ve welcomed brilliant graphic novel creators like Allie Brosh and Harvey Pekar. Literary organizations like McSweeney’s and Sister Spit performed at the show. And big-time novelists read, there, too, including Terry McMillan, Larry McMurtry in 1977, and Ursula K. LeGuin in 1998.

This year—so far, at least—there’s bupkis. Not even roving groups of local poets entertaining crowds as they wait to get into venues, as was featured at a Folklife festival a while back. Organizers couldn’t even be bothered to throw a little money at a great local literary magazine like Moss, or a literary organization like Jack Straw or Clarion West.

It’s just preposterous to me that Seattle’s preeminent arts festival doesn’t seem to feel the need to represent Seattle’s literary arts at all. We are a UNESCO-recognized City of Literature, for crying out loud! But the summer-ending arts festival, the big event that brings the city together to celebrate art for art’s sake, can’t even be bothered to host a single lousy reading?

I’m not going to suggest that people write Bumbershoot’s organizers and demand including a literary arts program. They’ve made it pretty clear they don’t want book people at their party.

I’m just mentioning it here because I think it’s a goddamn shame. That’s all.

I’ve Been Writing

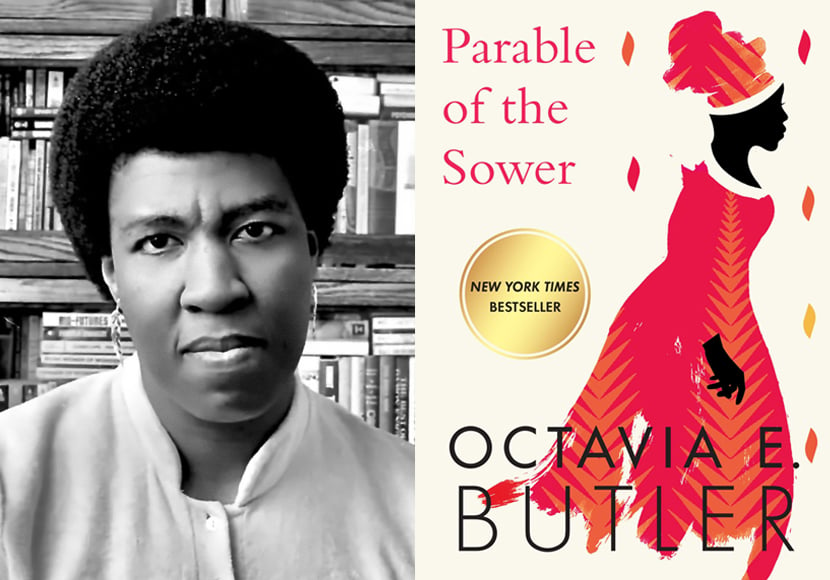

But while I am incredibly disappointed about Bumbershoot, I want to put it on the record that I am positively thrilled with this year’s Seattle Reads selection. Seattle Public Library is spending this spring and summer celebrating Octavia Butler and her incredible sci-fi book Parable of the Sower in book clubs, readings, panel events, and other programming all over the greater Seattle area. I wrote about it for the Seattle Times. I was especially thrilled to talk to local sci-fi writer Nisi Shawl, who was friends with Butler in her last few years here in the Seattle area.

I also previewed some of the best-looking March paperback releases for the Times.

And I profiled a pair of local authors this month, too. First, I talked to graphic memoirist Tessa Hulls about her astounding generational story Feeding Ghosts, which I think should be this year’s breakout graphic memoir. And then I talked with Seattle journalist Reagan Jackson about her new collection of journalism, Still True. These two women are positively crushing it, and I look forward to decades of great work from them.

And finally, I wrote about Kent’s Page Turner Books, a nerd-friendly new and used bookstore that has survived two disastrous ceiling collapses, only to come back bigger and stronger than ever. If you ever want to soak yourself in genre, you should get lost in the shelves of mass-market mysteries and sci-fi at Page Turner.

I’ve Been Reading

Speaking of genre mass-markets, I went on vacation this month and took an armload of pulpy paperbacks with me, so this section will be a little longer than usual. I read a collection of short pieces by Harlan Ellison, Stalking the Nightmare, that I remember loving toward the end of my teen years, but which didn’t do much for me anymore. Ellison’s work in general seems not to be aging too well, though big-name writers like Stephen King and Neil Gaiman still speak fondly of him.

Bob Fingerman’s Pariah is a post-apocalyptic novel about a woman with the power to repel zombies in a zombie-ridden world. Some of the characterization—particularly of the titular pariah—is killer, but the book’s pre-MeToo take on misogyny and sexual assault prevents me from recommending this too heartily.

I read two novels by popular 20th-century novelists who are now largely forgotten. The Storyteller is a semiautobiographical novel by Harold Robbins, who was one of the best-selling authors of the latter half of the 1900s. It was a positively dreadful read: sexist, racist, self-aggrandizing, no plot—trash in the most disparaging sense of the word. (I do recommend Andrew Wilson’s biography of Robbins, The Man Who Invented Sex, though—Robbins’s life is way more interesting than his work.)

Ira Levin, the other forgotten 20th-century giant, is a favorite novelist of mine. The plots of his novels are as taut as harp-strings, and he always has interesting genre ideas that feel deeply resonant with the human condition. You’ve definitely heard of movies based on his books: Rosemary’s Baby, The Stepford Wives, The Boys from Brazil, Sliver. This time I read A Kiss Before Dying, a Highsmith-style dark thriller that puts the reader into the head of a murderous sociopath and then shows the repercussions of his actions through the perspectives of people around him. I loved this one—a dark amusement park ride of a novel, for sure.

Gene Smith’s When the Cheering Stopped is a non-fiction account of President Woodrow Wilson’s stroke and his White House staff’s herculean efforts to hide the president’s poor health from the American people. This is a story that is somehow simultaneously more salacious and less salacious than what you’ve heard.

I read an old biography of Stanley Kubrick a few months ago, and it left me wanting something a little more comprehensive. So I read Robert Kolker’s Kubrick: An Odyssey, the latest biography of the director. This one scratched all my itches—behind-the-scenes gossip of the making of his films, insight into films that he never made, and mythbusting explanations of his strengths and weaknesses. Related: I watched Barry Lyndon for the first time last month and I was delighted to watch a film that was so transparently willed into being by one person.

I love the premise of Frederik Backman’s novel My Grandmother Asked Me to Tell You She’s Sorry. It’s told from the perspective of a young girl whose eccentric grandmother dies and leaves her a list of unfinished business to accomplish, and while some of the book is quite funny and tender, too much of it is mawkish and overwrought. It’s a great idea with nowhere to go.

Sloane Crosley’s Grief Is for People is one of those short books about grief that seem to have become a standalone literary genre. In this case, Crosley is writing about the death of a beloved friend who worked with her at the publicity department at Knopf. I’m not, thankfully, in the middle of grieving anyone, so I can’t attest to its healing power. But it’s a smart and clear-eyed story of friendship and loss, and even if it didn’t feel like the book successfully tied all its loose ends together, I still appreciated its elegance and emotion.

Acts of Service is a debut novel by Lillian Fishman about a young woman who gets swept into an open relationship. It’s one of those books where every character, in the right light, is a normal person disguised as a monster—but at the same time, you could easily see a nice young person in their 20s absolutely identifying with these characters on a fundamental level.

Katherine Min worked on the novel that would become The Fetishist for years. She envisioned it as a kind of Lolita, only about white men who fetishize Asian women. Now it’s been released as a posthumous publication, and it’s one of the better novels I’ve read in a while.

Betting on Dread

I don’t follow sports at all. And I mean at all. From the Olympics to baseball to soccer to a child’s tee-ball game, anything sports-related just bounces off my big dumb head. But I did briefly take notice in 2018, when the Supreme Court basically took the reins off sports betting in the case Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association and 36 states soon legalized sports betting.

At the time, I noticed it because it had the characteristics of most other modern Supreme Court decisions—smugly irresponsible, with the very real threat of dire consequences for ordinary people looming just overhead.

I feel like a bit character in the early part of a zombie movie—terrible things are happening in the background and I’m just barely noticing that something is amiss. Because I don’t watch sports on TV or read about sports in the media, I’ve been noticing small consequences lurch around slowly in the background.

For instance, I’ll be listening to a comedy podcast and a sports betting ad will come on—something that never would have happened ten years ago. I’ll glimpse an ad for a betting service on a cable TV playing at a restaurant. A pundit will make a reference to gambling in a way that feels so much more casual than it would have years ago.

Now, I’ve gathered from headlines that supposedly one of the best baseball players in America—a guy whose name I’d literally never heard before—is swept up in a gambling scandal. The consequences of the Court’s actions are gaining speed now, and they’re starting to do some damage.

The amazing thing about all this is how utterly obvious it is. We’ve seen what happens when you loosen the rules around sports betting. I am allergic to sports, but even I know about the Black Sox scandal. When you put this kind of temptation in front of a bunch of athletes—which is to say a dozens of highly competitive and impulsive young men with a lot of extra money and a shared feeling of invulnerability—they’re going to fall for it. This might be the first major scandal of the post-Murphy era, but even I know it won’t be the last.

And that’s just the beginning of this particular monster movie. I suspect in the next five years we’re going to see an uptick in young men ruining their lives, now that it’s ridiculously easy to bet on sports. We’ll see some app finally perfect making sports betting as addictive and easy as pulling the arm on a penny slot machine and then you’re going to have a small city's population worth of 22-year-old men pondering suicide because all of a sudden they’re $75,000 in the hole and they only make $22,000 a year. There’s a lot of misery, pain, and destruction coming our way, and along the way a handful of people are going to get insanely rich.

Again, anyone with an ounce of foresight could have predicted how this was going to go. But the Supreme Court, as it stands, is only interested in looking backward—at wondering what a bunch of dead slave owners in powdered wigs would do about gambling, or guns, or abortion. And the Court's colonial cosplay is going to immiserate and kill hundreds of thousands of people before we get the opportunity to repair the damage they’ve done.

We’ve got to fix our judicial system. We need term limits for judges, because only royalty should be given titles for life. We need to make sure that judges have to live with the consequences of their actions, the same way all of us do. Top to bottom, we need to reform the whole damn judicial system so judges don't just wallow in their own corruption. That’s my point. That’s what I want to say.

This has been an intense one! Sorry. Hope your spring is going well. See you at the end of April!

Paul