My Year of Less

Hello,

Can we bear one more conversation about social media? I am pleased to report that Twitter has started sending me panicked emails to point out tweets that I may have missed because I’m not spending any time on the site anymore. Facebook has been sending me these emails for years, since I basically left my FB profile to rot in the wake of the 2016 election, and Twitter’s reminder emails are exactly as enticing as Facebook’s emails—which is to say, not at all.

I’m still futzing about with Mastodon, I’ve posted a little bit on Post, and I’ve followed the comics community to the alarmingly rickety Hive, but I’m in no hurry to establish a permanent online home. I’m just reveling in the liberating feeling of unmooring from a service that not so long ago felt as essential to my being as my typing fingers.

Looking back, my theme for 2022 has been saying and doing less. I’ve written fewer public-facing pieces than any other year since I started working at The Stranger in 2008. I’ve done almost no public events this year, aside from an author introduction or two. And I’ve basically shut up more than any time in the last 14 years.

I understand that being quiet is a privilege. I have a full-time job that means I don’t have to be continually hustling the way most freelance writers do, and I have a few gigs that give me a regular outlet for freelance pieces. But I’ve basically been sprinting with my writing since 2008—writing quick responses to current events, synthesizing immediate opinions on art, interacting with Seattle’s cultural community in real time in the form of interviews, previews, and reviews. This year feels like the first time I was really able to get off the merry-go-round, take a look at my surroundings, figure out how I feel, and say no to experiences that don’t feel right.

Hopefully, 2023 will be a rebuilding year. I’m looking forward to trying new things with my writing, publishing more comics, and finding different ways to interact with the world that don’t feel as disposable as my old prolific blog-happy job. But it’s become clear in the last month that getting rid of Twitter was the final, and perhaps most important, step in slowing my brain down and setting my mind to thinking about what I really want to do as a writer.

I’ve been writing

My bookstore profile in this month’s Seattle Times is of Moonraker Books, a gorgeous bookstore on Whidbey Island that is celebrating 50 years of continuous operation under the same owner. This is one of the greater Seattle area’s bookstore gems, and owner Josh Hauser is a world-class bookseller. I’m glad she’s getting so much recognition this year.

For Insider, I did a deep dive into the proposed Kroger-Albertsons merger, and why virtually every big corporate merger should be shot down. The Biden Administration is doing something very exciting right now by rewriting corporate merger rules, and they have the opportunity to unspool a lot of the greed that has controlled the economy since the Reagan Administration made it easy for corporations to swallow each other up.

Few conversations in life are as satisfying as talking to booksellers about the new books they love. Also at the Seattle Times I interviewed four incredible local booksellers to learn more about the books they’re excited to sell this holiday season. I’ve read three of these ten books, and I’m excited to read the other seven now.

Post.News is one of the social media sites that has popped up in the disastrous collapse of Twitter, and it’s a very appealing idea: A community centered around journalism and conversation. I was accepted to a very early beta version of the site, and writing on it feels a little like a cross between Twitter and Medium. I especially like that you can use micropayments to pay to read individual articles from contributing news sites. Anyway, on Post.News, I wrote a…well…a post about my personal moderation policy. I don’t think I’ve ever written about this anywhere else, but to sum up: My social media policy is block early and block often. You don’t owe your attention to anyone.

I’ve been reading

Ducks, Kate Beaton’s memoir about working for two years on a remote Alberta oil refinery, is a miracle of comic-book storytelling. It’s a story that couldn’t be told as well in any other medium. Beaton captures the all-encompassing monotony of working a menial job, but the visual aspect of comics, and the fact that a comics reader can move forward at their own pace, makes it work. As a movie or a novel, this would be deadly dull, but Beaton’s charming art and masterful pacing transform this into a page-turner. And I was pleasantly surprised by another comic memoir this month: Zoe Thorogood’s It’s Lonely at the Centre of the Earth. This memoir, about a young cartoonist struggling with depression at the exact moment that she began to experience professional success as a cartoonist, is one of the most masterful books I’ve seen from a young artist—the way Thorogood employs a variety of styles to depict her shifting mental state is absolutely breathtaking.

Andy Campbell’s We Are Proud Boys is an incredibly depressing, but very important, work of journalism—a history of the white supremacist organization from its unlikely origins at Vice Magazine up to the aftermath of the January 6th insurrection. I haven’t read a better book-length explanation of the rise of the alt-right, and it helped me understand exactly how a bunch of scattered misanthropes could become a democracy-threatening movement. As an antidote to the darkness, I recommend following this one up with John Keane’s The Shortest History of Democracy, an excellent (and brief) book that reveals the durability of democracy as a concept through human history. Individual democracies may be snuffed out by fascists not unlike the Proud Boys, but the ideal of democracy itself seems, happily, to be almost as old as humanity.

Embarrassing admission: I’ve never read a Marilynne Robinson novel before this month. As a bookseller, and then as a book critic, I tended to skip over the hugely popular books that enjoyed universal acclaim—Robinson’s books sold themselves, and they were praised in outlets around the world, so the chorus hardly needed my voice. I finally read a copy of Gilead that I found in a Little Free Library in Seward Park, and my instincts were correct: I honestly don’t have much to add to the conversation. It’s a big-hearted, intelligent, elegantly constructed novel about the human spirit, I’m glad I read it, and I’m excited to read the rest of her books.

I read a variety of nonfiction books this month including the anthropological exploration of rituals and their use for human life, Ritual: How Seemingly Senseless Acts Make Life Worth Living, by Dimitris Xygalatas, and a trilogy of books about consciousness in animals: How to Be Animal by Melanie Challenger, The Mind of a Bee by Lars Chittka, and When Animals Dream by David M. Pena-Guzman. Ever since I started sharing my home with dogs, I’ve been fascinated by their perceptiveness and intrigued by what’s going on in their heads. And the more I read about animal consciousness, the thinner the line between humans and animals becomes. Anyone who argues that humans are uniquely special or above the rest of nature is, in my estimation, an idiot.

Speaking of the dogs, it’s been a bit since I’ve shared a photo. That’s Wallace on the left. Since he turned four this summer, he’s really chilled out and relaxed into a friendly pup. Oberon, on the right, is still excited for three-mile walks despite his arthritic hip, and he’s entering old age with a boundless enthusiasm for cuddling.

Putting meat on the bones

One of the things I love about writing comics is the fact that there is no standard format for a comic script. Pretty much every comic book writer formats their script differently. I’m sure this is a nightmare for editors and, sometimes, for artists. But to me it feels fun and casual—a reminder that none of this is a science and it’s all intuition at heart. And it’s caused me to experiment with my writing in ways that would never have occurred to me with my prose.

For instance, I have never successfully been able to outline a piece of writing before. Something about working from an outline drains all the fun out of writing for me—it turns the exploratory art of writing into a boring game of connect-the-dots.

But I’m working on a short comics story for an anthology, and I decided to try a new technique with this script:

First, I write a brief sentence explaining what happens on each page.

Then, I write a short sentence for every panel on the page, explaining the action in each panel in really simple terms.

Then, I do another pass to fill out the visual detail in each panel.

Finally, I write the dialogue.

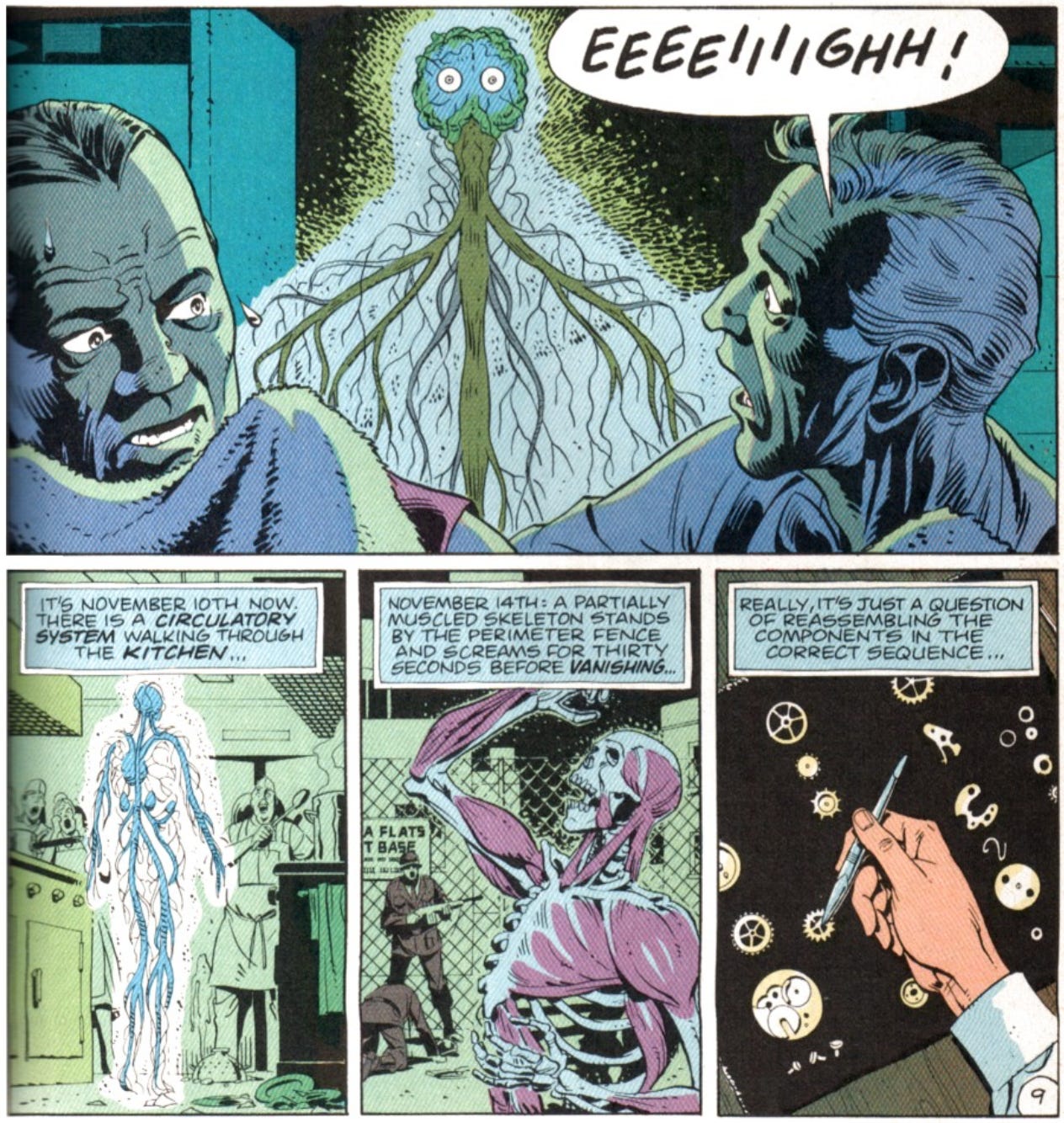

I think of this like the brilliant scene in Moore and Gibbons’s Watchmen, in which Dr. Manhattan explodes to atoms in a nuclear disaster and then reassembles himself from basically nothing over the span of days:

Something about this process feels uniquely suited for writing comics. It melts down each page and panel to its essential action, while also leaving space for all the details, allowing me to add them in as the story deepens. Comics are a visual-first medium, and this method allows me to think of the art in a cartoonier, more action-oriented way.

The previous method that I used—just writing the whole script from beginning to end, like a piece of prose—felt a little too writerly, a little too obsessed with the language over the art. This way feels more respectful of both the artist and the medium. It’s exciting to be experimenting with the fundamentals of writing in a medium like this—to admit that I don’t know anything and to try techniques that previously never worked.

Above all else, I’m just happy to still be learning.

I hope you’re learning, too.

Paul