Information Doesn't Want to Be Free

Hi!

Next week, the annual Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) conference is happening in Seattle. There will be a ton of panels, parties, and readings, and much of the evening programming is free and open to the public in venues around the city. I’m participating in a couple of AWP events this year—one at the conference that you need to be a badge-holder to attend, and one free evening event open to all.

At AWP, I’m hosting a panel with representatives from four great Canadian independent publishers—Book*hug, Coach House, Drawn & Quarterly, and Invisible—to talk about what it’s like being in the book business when the country next door is home to the largest corporate mega-publishers in the world. That’s happening Saturday March 11th at 9 a.m. in rooms 440-442 in the Convention Center. If you’re attending AWP, I hope you’ll start your day off with us; these publishers are doing great work and I can’t wait to talk to them about it.

And I’m taking part in an AWP offsite event that’s free and open to the public: A celebration of Seattle poet Denise Levertov at Elliott Bay Book Company on Wednesday, March 8th at 7 p.m. Local poets Claudia Castro Luna and Jan Wallace will join Elliott Bay readings coordinator Rick Simonson and me in sharing some of our favorite poems by Levertov, who is in my opinion one of the most underrated poets of the 20th Century. If you’re a Levertov fan, we’d love to have you come and share a story about her life, or one of your favorite Levertov poems. If you’ve never heard of her before, I hope you’ll come and learn about her. The event is intended to be a celebration of her life, and a reminder to the poets and writers visiting Seattle for AWP that they’re walking in the footsteps of giants.

That’s right—I’m doing two events in one month! Not bad for a bitter recluse. (And last month, I also took part in a panel at Winter Institute, the annual bookseller education conference, which I think already makes 2023 the most action-packed year I’ve had since 2019.) Things don’t feel “back to normal” yet—I don’t think they ever will, honestly—but I’m excited to talk with people and get out into the world a little bit. If you’re able to attend, I hope to see you at either or both of those events.

I’ve been writing

This month, I contributed to the Seattle Times’s weeklong celebration of the city’s many museums with a piece exploring the literary programming of Ballard’s National Nordic Museum. This piece also doubles as a sneak preview of an interesting AWP offsite event—a reading of Icelandic-themed poetry happening at the museum at 6 p.m. on March 8th. Maybe it’s just an aftereffect of the pandemic, but many of Seattle’s museums seem to be pulling back on literary programming. It’s good to see the National Nordic Museum flip the script and lean even harder into books, readings, and other literary events.

I don’t say this often, but I’m very fond of my piece in the Seattle Times this month profiling Peter Miller, who has been selling design and architecture books at Peter Miller Books in Pioneer Square and Belltown for over 45 years. Miller is an absolute genius, and he has very strong opinions about what it means to own and operate a shop. His love of design has subsumed every inch of his beautiful storefront, from the gorgeous cheese graters and dishtowel holders to the world-class collection of architecture and design titles that he sells. He’s a Seattle original. I was so pleased to talk with him, and honored to write about his shop.

And on the Pitchfork Economics podcast today, Goldy and I interview author Rick Wartzman about Walmart's long internal push-and-pull about raising employee wages. Wartzman's new book, Still Broke, documents how Walmart moved from an exploitative employer to a slightly less exploitative employer in an exploration of the benefits and drawbacks of socially conscious capitalism. At the top of the episode, I also reveal a piece of my sordid past by discussing my brief history as a Walmart employee in Colorado Springs.

I’ve been reading

I fell head-first into the early work of George Schuyler this month. Schuyler was a Black novelist who used science fiction—specifically, what we now call Afrofuturism—to explore race and racism in America. First, his 1931 novel Black No More imagines what might happen when a scientist invents a device that can turn Black people white. And second, originally published as a serial in the mid-30s, Black Empire is an adventure novel about a super-genius who decides to fight against racism and inequality by creating a global Black revolution and establishing a nation in Africa—kind of a Black Atlas Shrugged, only way more entertaining. If you’re only going to read one book by Schuyler, I recommend Black No More over Black Empire, because it’s a better-written book and the satire in Empire gets a little rough. (You can easily spot the seams of the serialized chapters of Black Empire, making it kind of a bumpy narrative ride when read as a novel.) But happily, you don’t have to choose. Schuyler deserves credit as a clear trailblazer for the social sci-fi writers who followed several decades later—writers like Kurt Vonnegut, Philip K. Dick, and Ursula K. LeGuin.

I suspect that a big reason why Schuyler hasn’t stayed in the public eye is that he held a lot of controversial, and frankly wrong, views. He refuted his early socialist leanings and became more and more conservative throughout his life, dismissing the Harlem Renaissance early in his career and arguing against the end of segregation later on—to the delight of the John Birch Society, who published many of his later columns. He denounced both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr, and white racists loved to use Schuyler as an ideological shield when they protested the civil rights movement. But I think the progression of Schuyler’s life is a fascinating one that is well worth studying, and even though I don’t agree with all the ideas and perspectives in these two books, I still believe that they’re great American novels.

On the lighter side of sci-fi, Seth Fried’s The Municipalists is a buddy-detective novel set in a utopian future—and one of the detectives happens to be an artificial intelligence. Given that the whole world is losing its collective mind over AI right now, the story felt a little more like a speculative documentary than it probably did when it was published. It’s a funny book, with some great worldbuilding around the utopian sci-fi city and its culture.

A Heart That Works is comedian Rob Delaney’s short memoir about losing a very young child to cancer. It’s heartbreaking, but, like much of Delaney’s writing and standup, it’s also bracingly honest and angry and weirdly cheerful. I don’t recommend reading this one if you’re currently Going Through It—and by It I mean anything from depression to grief to even mild heartbreak—but if you’re in an emotional place to consider things like grief and the random cruelty of the universe, Delaney has many worthwhile insights to offer.

Because President Biden’s Chief of Staff Ron Klain stepped down this month, I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to be a president’s chief of staff. It seems to me to be possibly the most difficult job on the planet—all the emotional and intellectual turmoil of being president with almost none of the perks—and I wanted to learn more about the men who’ve held the job (and, yes, they’re all men to date.) Chris Whipple’s The Gatekeepers profiles every White House chief of staff from the Nixon administration through the Trump administration, and it’s a good overview of the position and the personality traits necessary to thrive as a chief of staff. At times, the book just falls back into rote recounting of modern presidential history, but there’s enough access and insight to make the book worthwhile.

Heather Radke’s Butts: A Backstory is a bestselling history and critical examination of society’s attitudes toward female butts that’s been on the Peaks Picks shelf of my local library for months. I enjoyed it! The book explores the racism, misogyny, and self-loathing that has been centered around women’s bodies, through a butt-centric lens. Radke’s history begins with the horrifying story of Sarah Baartman, the African woman who was paraded around Britain in the early 1800s as an object of curiosity, derision, and scorn, and it ends with the rise of Jennifer Lopez and pop culture’s newfound appreciation for large butts. Some of the social criticism feels dated in a very 1990s, let’s-impress-the-cultural-studies-professor kind of way, but the book is a fast and informative overview of a subject that until recently would have been considered too frivolous or prurient for a whole book.

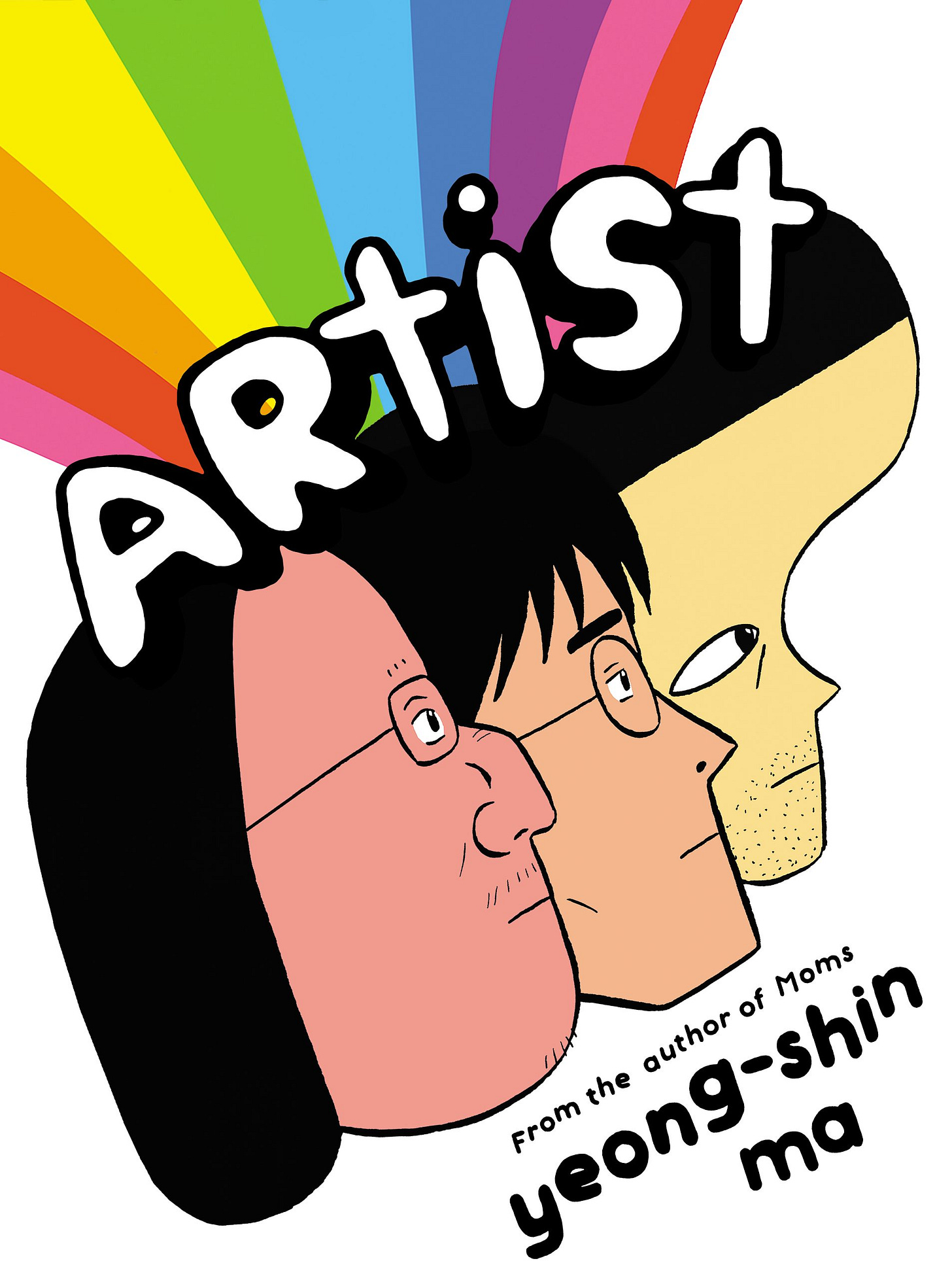

Yeong-shin Ma’s graphic novel Artist is a satire about three middle-aged artists who find varying degrees of commercial success. The story covers a lot of ground, from cancel culture to criticism to the idea of selling out, and the book develops all three protagonists into fully rounded characters when it would have been easy to simply mock them. I’m intrigued by Ma’s decision to render one of the artists with a giant head that resembles the Elephant Man—you can see him on the right of the cover, above. While Ma’s art is definitely cartoony, the other characters in the book are portrayed more or less with realistic proportions and characteristics, and I have to say the choice pulled me out of the story a little bit. I’d love to ask Ma for the reasoning behind the decision, because it’s a bold choice.

I’m currently obsessed with Charles Soule and Ryan Browne’s comic book 8 Billion Genies, which imagines what might happen if everyone on earth suddenly was given a genie who granted them a single wish. The book is coming out in periodical form, so the story is not over yet, but it’s definitely been a highlight of my comic-reading life over the past year. I’ve enjoyed Genies so much that I decided to try Soule and Browne’s previous comic, which has been collected in a thick omnibus titled Curse Words: The Hole Damn Thing. It’s an urban fantasy about a wizard named Wizord who escapes a mystical realm and tries to take up residence in the real world, and while it’s not as elegant and provocative as Genies, it’s definitely a big old fun slab of imaginative adventure comics.

A few notes on the care and feeding of writers

A little while ago, I posted a link on Mastodon to a piece that I wrote in the Seattle Times. In the replies to the post, someone complained about the Times’s paywall and linked instead to another piece about the same subject, written by someone else, in a publication that doesn’t have a paywall. (I don’t want to publicly shame this person, so please don’t go looking for him.)

I tried to gently point out that it was rude to link to another story in the replies to my post, and that the paywall helped to pay for the labor that it took to write my piece, and the person replied with another anti-paywall screed. At that point, I just blocked him and moved on because arguments on social media are pointless.

This interaction did make me want to send a Public Service Announcement out into the world, though: Try to remember that writers are people, too.

Look, I get that paywalls can be frustrating. For publications, paywalls are possibly the most successful way to pay for overhead. Online advertising has basically become worthless thanks to Google and the other big tech companies, while subscriptions are fairly reliable and ensure a consistent base of regular readers. So everyone is doing a paywall model, and every paywall has a different and confusing set of rules about how many “free” stories you can read over a certain period of time.

For decades, the internet has operated under the concept that “information wants to be free”—that people will share information and art that they love, and that the best stuff will spread widely. I think the last 7 or 8 years has proven the lie behind that expression. Information doesn’t want to be free—gossip wants to be free. Misinformation wants to be free. Propaganda wants to be free. True and meaningful information costs money and takes time to produce. You have to commit to reading good information. A shitty anti-vaxx meme will circle the globe thirty times before some reporter atVox manages to source, collate, and publish a cogent and thorough refutation of the lies in the meme, and their story will enjoy a fraction of the meme’s reach. Nothing about the creation and dissemination of information is free or easy.

With all that said, I do jump paywalls—and I feel perfectly morally fine about doing so because nobody could reasonably expect me to shell out for an annual subscription to a newspaper in Minneapolis in order to read a single story. (If the paper asked for some pocket change via Apple Pay in order to read a single story, I’d happily pay that, but micropayments are for whatever reason a nut that the internet hasn’t managed to crack over the span of 30 years.) Financially speaking, I simply can’t afford to subscribe to every publication that I read in the span of year. You have to pick the outlets that you read and care about the most, and that’s where you have to put your subscription dollars to work.

But it’s a basic human kindness to not respond to a writer with someone else’s story and launch into a high-minded conversation about whether paywalls are legit or not. Many of us jump paywalls out of necessity. But because paywalls pay the bills for thousands of writers, we should at the very least shut up when talking to the writers whose labor is funded by the paywall.

And I know someone might try to extrapolate my “jumping a paywall is okay now and then as long as you don’t brag about it to the writer” stance into an admission that it’s okay to pirate my comics. But that analogy doesn’t track, because you can right now take my comics out for free from your local library, or you can request copies via interlibrary loan. (And in fact, I frequently use my Seattle Public Library card to gain online access to newspapers and magazines that I don’t subscribe to, which I consider to be just as morally sound as taking a book out from the library.)

I love to hear from people who take my books out from the library. Hell, I encourage you to borrow my comics from the library. But if you tell me that you pirated one of my comics, all I hear is that you stole money from my friends—the artist who spent months crouched over their drawing boards, the publishers and editors who care enough about comics to devote their whole lives to bringing them into the world.

In short, what I’m saying is that writers (and editors, and publishers, and everyone else involved in writing and publishing words) are people, too, and you should always try to treat people at least as well as the way you’d want to be treated if the roles were reversed. If you don’t follow that rule, I’m not going to interact with you. Some (idiots) might call that cancel culture, but really it’s just the basic requirement for being a person who lives in a society.

Hope this finds you well, and maybe I’ll see you out in the world this month?

Paul