#35 - The Singular vs The Systemic (Not boring, honest)

Good morning from Manchester.

I've been here all week as part of an R&D project focused on Manchester Museum and the decolonising of museums. Aside from getting to talk to a lot of smart and fiercely curious people, I would like to brag that it has not rained the entire time I've been here. Sure, it's a little damp on this final day but otherwise it's been a bright and dry week for my soul/soles.

Even though I've been to this city before it's never been for more than 15 or so hours at a time so I've appreciated getting to walk the streets and literally feel the stones, Sam Vimes style, due to the thinness of my shoes. I think what's struck me most is how empty the place feels. Not objectively, obviously. There has been no zombie apocalypse up here, but in comparison to London where the expectation is on everywhere being busy at all times. I like this better.

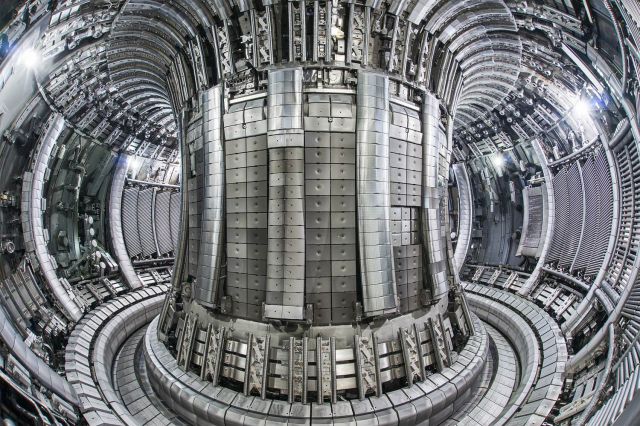

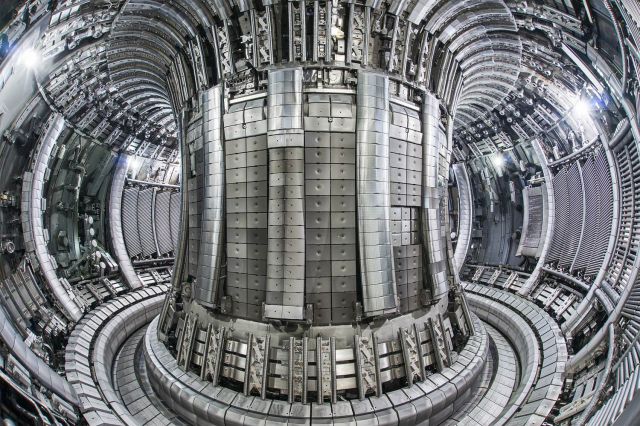

On Tuesday I managed to visit the Royal Exchange for the very first time and my sense of shame at the belatedness of this visit was quickly replaced by awe. It is exactly as stunning a building as I'd imagined and I was struck by how the physical journey is so different to a usual trip to the theatre or any arts space really. Most places you go to, the entrances and foyers are quite small and tight and it's on entering the theatre itself that the space opens up. Here, while the theatre itself is a marvel, entering it from a cavernous space put my head into a completely different place. It made me think of nuclear fusion reactor because my mind is like that:

Tenuous, but I quite like the metaphor it suggests about the process of pulling a production together.

Tenuous, but I quite like the metaphor it suggests about the process of pulling a production together.

The play I saw there was Simon Stephen's latest and Sarah Frankcom's last as artistic director. It's a play built on snapshots of a family across the north of England and while I walked out at the interval uncertain if it would meaningfully cohere, it clicks together so gently and with such warmth in the second half it's hard not to be thoroughly disarmed by it. It's such a confidently low-key production, you get absorbed by the details. The humanity in the mismatched chairs at a funeral nearly properly sent me. And the actors! Blimey. It almost feels like cheating when they're that good.

Making my way through notes and research for the project, I find myself zooming in and out of this question of decolonisation, trying to figure out the best way to humanise what must feel like a dry, academic idea to most people who casually encounter it. The go-to here is to dig into the lives of individuals involved in the procurement of the items the museum holds. One of the people I spoke to this week agreed that the displays and stories should reflect the provenance of the objects in the museum more directly. They did question, however, the extent to which we should seek to blanket blame individuals within the system of empire. Is a young frontier policeman from a poor family, capturing butterflies near his post in Sierra Leone the same as a wealthy man who commissions a professional collector to go out into the world on their behalf, sometimes literally on military vessels seeking to impose control over foreign nations?

On one level, yes, abso-fucking-loot-(pun intended)-ly. There is still the choice of the individual to take part in the imperial project and we should give them the dignity of that choice, for better or worse. Yet, emotionally, the intents and motivations feel distinctly different. One feels mercenary, one feels almost incidental to the experience, like collecting shells at the beach. You join the army perhaps because it's a secure job, not because you luv too dominate and exploit in the name of the Crown. And then, yet, again, if the damage does is the same, what does intent matter?

I've been thinking on this so much of late - the moral nature of nuance, what it means to try and find the balance between the singular and the systemic. How sometimes the meta-narrative crushes out the individual narrative to the detriment of our humanity. How, also, we can't allow pleas to the personal to rob us of our resolve to make meaningful change. How we can draw the wrong conclusions and take the wrong actions on the basis of a tantalising statistic that confirms our beliefs.

As an example - bringing things back to Manchester - the Royal Exchange's biennial Bruntwood Prize announces its winners on Monday. As someone who used to be a reader for both theatre and prizes, I'm interested in the methodologies different organisations use and the results it throws out. Bruntwood is a competition where the entries are anonymous which, theoretically, removes biases in the judging process that might lead to the reinforcement of traditional hierarchies when drawing up the shortlist and eventual winners.

This year, the prize managed to produce a UK/Irish shortlist where half of the writers are Oxbridge graduates, as far as I can ascertain. On the face of it, that is a striking statistic. When you hear it, you can also hear the headlines you might draw up about it. It confirms everything you think about the posh/middle-class/elite issues theatre has. Even an anonymised process can't weed it out. Or, the right-wing variant would perhaps go: Doesn't this just prove they're just better?

But, if you take a moment to look at the prize's recent history of shortlist and winners, the conclusions don't really hold up and suggests this year's pattern is anomalous and not statistically significant. Furthermore, I know some of the people on that list. Some are friends, some are acquaintances and all of their stories are routes into theatre are completely different. There's early success in there, slow burners, career-changers etc etc. Binding them all around that singular statistic does them a disservice and doesn't really give us much except, perhaps, being a small reminder that prizes can't replace a network of well run and energetic commissioning departments if you want to have consistency over the work you support and programme, as well as an oversight over who needs more help to reach their fullest potential.

Let's be clear - there are absolutely systemic issues that we should have no hesitancy in jumping on and confronting. Also, this doesn't mean there aren't other issues of biases here - for example, I think you can draw some conclusions about, say, the dominance of writers with some degree of higher education, in theatres even though that's only half the country. I suppose this is more a plea to myself to resist the temptation of making instant conclusions that confirm my expectations without doing more of the work and figuring out how to frame those conclusions in a way that leads to constructive actions that are mindful of the feelings and different situations of individuals when necessary. More doubt + more curiosity = more humanity, better outcomes. (I hope).

That's me over the limit. See you next week x

If you're new to Patelograms and like what you've read, you can subscribe by clicking here.

If you're an old hand, thanks as ever for taking the time.

I've been here all week as part of an R&D project focused on Manchester Museum and the decolonising of museums. Aside from getting to talk to a lot of smart and fiercely curious people, I would like to brag that it has not rained the entire time I've been here. Sure, it's a little damp on this final day but otherwise it's been a bright and dry week for my soul/soles.

Even though I've been to this city before it's never been for more than 15 or so hours at a time so I've appreciated getting to walk the streets and literally feel the stones, Sam Vimes style, due to the thinness of my shoes. I think what's struck me most is how empty the place feels. Not objectively, obviously. There has been no zombie apocalypse up here, but in comparison to London where the expectation is on everywhere being busy at all times. I like this better.

On Tuesday I managed to visit the Royal Exchange for the very first time and my sense of shame at the belatedness of this visit was quickly replaced by awe. It is exactly as stunning a building as I'd imagined and I was struck by how the physical journey is so different to a usual trip to the theatre or any arts space really. Most places you go to, the entrances and foyers are quite small and tight and it's on entering the theatre itself that the space opens up. Here, while the theatre itself is a marvel, entering it from a cavernous space put my head into a completely different place. It made me think of nuclear fusion reactor because my mind is like that:

Tenuous, but I quite like the metaphor it suggests about the process of pulling a production together.

Tenuous, but I quite like the metaphor it suggests about the process of pulling a production together.The play I saw there was Simon Stephen's latest and Sarah Frankcom's last as artistic director. It's a play built on snapshots of a family across the north of England and while I walked out at the interval uncertain if it would meaningfully cohere, it clicks together so gently and with such warmth in the second half it's hard not to be thoroughly disarmed by it. It's such a confidently low-key production, you get absorbed by the details. The humanity in the mismatched chairs at a funeral nearly properly sent me. And the actors! Blimey. It almost feels like cheating when they're that good.

Making my way through notes and research for the project, I find myself zooming in and out of this question of decolonisation, trying to figure out the best way to humanise what must feel like a dry, academic idea to most people who casually encounter it. The go-to here is to dig into the lives of individuals involved in the procurement of the items the museum holds. One of the people I spoke to this week agreed that the displays and stories should reflect the provenance of the objects in the museum more directly. They did question, however, the extent to which we should seek to blanket blame individuals within the system of empire. Is a young frontier policeman from a poor family, capturing butterflies near his post in Sierra Leone the same as a wealthy man who commissions a professional collector to go out into the world on their behalf, sometimes literally on military vessels seeking to impose control over foreign nations?

On one level, yes, abso-fucking-loot-(pun intended)-ly. There is still the choice of the individual to take part in the imperial project and we should give them the dignity of that choice, for better or worse. Yet, emotionally, the intents and motivations feel distinctly different. One feels mercenary, one feels almost incidental to the experience, like collecting shells at the beach. You join the army perhaps because it's a secure job, not because you luv too dominate and exploit in the name of the Crown. And then, yet, again, if the damage does is the same, what does intent matter?

I've been thinking on this so much of late - the moral nature of nuance, what it means to try and find the balance between the singular and the systemic. How sometimes the meta-narrative crushes out the individual narrative to the detriment of our humanity. How, also, we can't allow pleas to the personal to rob us of our resolve to make meaningful change. How we can draw the wrong conclusions and take the wrong actions on the basis of a tantalising statistic that confirms our beliefs.

As an example - bringing things back to Manchester - the Royal Exchange's biennial Bruntwood Prize announces its winners on Monday. As someone who used to be a reader for both theatre and prizes, I'm interested in the methodologies different organisations use and the results it throws out. Bruntwood is a competition where the entries are anonymous which, theoretically, removes biases in the judging process that might lead to the reinforcement of traditional hierarchies when drawing up the shortlist and eventual winners.

This year, the prize managed to produce a UK/Irish shortlist where half of the writers are Oxbridge graduates, as far as I can ascertain. On the face of it, that is a striking statistic. When you hear it, you can also hear the headlines you might draw up about it. It confirms everything you think about the posh/middle-class/elite issues theatre has. Even an anonymised process can't weed it out. Or, the right-wing variant would perhaps go: Doesn't this just prove they're just better?

But, if you take a moment to look at the prize's recent history of shortlist and winners, the conclusions don't really hold up and suggests this year's pattern is anomalous and not statistically significant. Furthermore, I know some of the people on that list. Some are friends, some are acquaintances and all of their stories are routes into theatre are completely different. There's early success in there, slow burners, career-changers etc etc. Binding them all around that singular statistic does them a disservice and doesn't really give us much except, perhaps, being a small reminder that prizes can't replace a network of well run and energetic commissioning departments if you want to have consistency over the work you support and programme, as well as an oversight over who needs more help to reach their fullest potential.

Let's be clear - there are absolutely systemic issues that we should have no hesitancy in jumping on and confronting. Also, this doesn't mean there aren't other issues of biases here - for example, I think you can draw some conclusions about, say, the dominance of writers with some degree of higher education, in theatres even though that's only half the country. I suppose this is more a plea to myself to resist the temptation of making instant conclusions that confirm my expectations without doing more of the work and figuring out how to frame those conclusions in a way that leads to constructive actions that are mindful of the feelings and different situations of individuals when necessary. More doubt + more curiosity = more humanity, better outcomes. (I hope).

That's me over the limit. See you next week x

If you're new to Patelograms and like what you've read, you can subscribe by clicking here.

If you're an old hand, thanks as ever for taking the time.

Don't miss what's next. Subscribe to patelograms: