[BONUS] The Hummingbird and Other Musings - issue 190 - 11th September, 2022

The Hummingbird

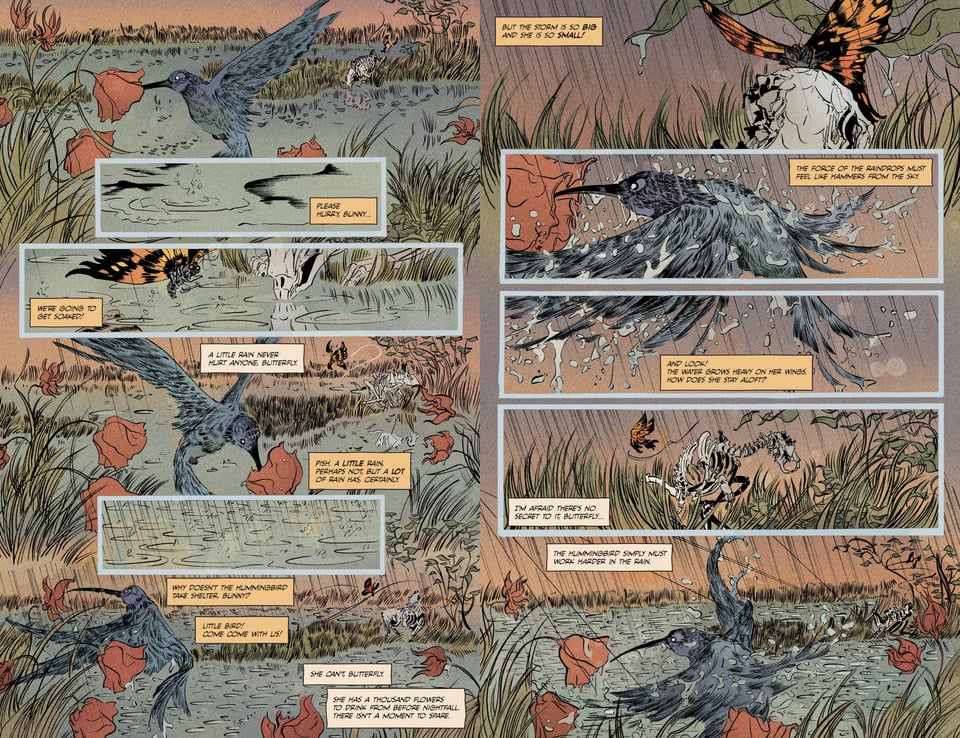

If you’ve not read Pretty Deadly, I highly recommend it. Written by Kelly Sue DeConnick, it’s a horror western wrapped up in mythology and questions of death, with beautiful art by Emma Ríos.

The story is narrated (after a fashion) by a butterfly and an undead rabbit – not dissimilar to the somewhat hyperactive robot narrators of Jodorowsky’s The Metabarons – with each issue beginning with a related story, aside, or lesson being told between the two non-human characters.

The below comes from Volume One, Issue Five (click to enlarge):

This passage, and the above line in particular, really struck me on a re-read. In some ways my depression is quite mild in that on my worst days I can still get out of bed, feed myself, shower, even attend to the day job. I can always – so far at least – do what needs to be done1 even as I’m being crushed beneath the weight of depression and self-loathing. On the other hand, the depression, however mild, has been constant for around twenty years.

Twenty years. That’s two decades of fighting back against the near-constant rain of a mind that hates itself. It is fucking exhausting on its own, but what’s worse is the knowledge that it might never change. That I might always have to fight this battle until one day when I’m simply too tired to carry on. I’m in therapy, I’m seeing a psychiatrist to try and take a more involved pharmaceutical approach too, but I’m not particularly hopeful. Hope could end up hurting if relief never comes to pass2.

We’re all hummingbirds. We all have a thousand flowers to visit each day just to maintain, just to keep going. Some of us are doing it in fine weather, some are doing it in the rain. Others still are caught in a catastrophic storm.

There’s a quote from Kurt Vonnegut you’re almost certainly familiar with:

My Uncle Alex, who is up in Heaven now, one of the things he found objectionable about human beings was that they so rarely noticed it when times were sweet. We could be drinking lemonade in the shade of an apple tree in the summertime, and Uncle Alex would interrupt the conversation to say, “If this isn’t nice, what is?”

So I hope that you will do the same for the rest of your lives. When things are going sweetly and peacefully, please pause a moment, and then say out loud, “If this isn’t nice, what is?”

It’s something I haven’t quite internalised yet, but which I’m trying to embrace. Those moments of good weather might be rare. They are worth noting, they are worth the moment of contemplation and enjoyment because maybe the rains are coming, and if you don’t take notice, maybe the rains will be all you can remember.

Too Much Dick

I’m seeing my therapist (psychologist, for those playing along at home) in-person again for the first time since the pandemic began. After our first session back in the office, I had a thought that maybe she would realise the person sitting across from her was not the same as the person she’d been talking to over videochat these past two years.

I’ve read too much Philip K. Dick. It’s the only explanation.

Worrying I’m not who I am is a rare one. Far more common is the fear that the world as I perceive it is not the real world. That I am actually so mentally ill (or to be more precise, the sort of mentally ill) that I am entirely disconnected from reality. It’s an odd and irrational fear. One that bubbles up at random intervals. There is no evidence to support the fear, no reason to believe it might be true, no history of reality slippages (that I’m aware of), just a niggling itch in the back of my mind.

It’s not helped by my readings into neuroscience and philosophy, where questions and pronouncements on the nature of reality and human perception only undermine any notion of a tangible reality. It’s not that I’m not crazy because my perception of reality is correct despite my fears, it’s that I’m not crazy because perhaps none of us should feel as certain as we generally do.

Dark Phoenix

I re-watched X-Men: Dark Phoenix recently. None of the second-generation X-Men sequels can compare to X-Men: First Class, but I felt the desire to revisit them for some strange reason.

There’s a moment at what would be the film’s dark night of the soul where Jean Grey looks down on Professor Xavier from an upstairs balcony, feeling very arch with her newfound power and knowledge of Charles’ earlier lies. Using her telekinetic gifts, she lifts Charles out of his wheelchair and treats him like a puppet, making him walk up the stairs, his legs unfeeling lengths of flesh given unnatural life.

It’s a small moment in a middling superhero movie, but if affected me because of the petty cruelty on display. Jean could have lifted him up and made him float through the air to gently touch down in front of her. Instead, she forces him to enact this pantomime of walking, demeaning him for no other reason than she can, because she is more powerful than him, than anyone.

Those few seconds of film made me depressed (admittedly that’s not particularly hard) because it’s a microcosm of what happens all around the world every single day. People with immense power (in the form of capital, rather than telekinesis, telepathy and all the rest supercharged by contact with an alien energy) happily subject countless people to demeaning, dehumanising, dangerous work, just so they might continue to accrue wealth and power.

The elite are no longer truly people, they have allowed themselves to become avatars for capitalist suffering. And as long as they continue to live their lives of opulence, they will never recognise the pain they have caused because they do not consider the rest of us to be human. We are resources and little more.

It might sound like I’m reaching, but the only way to understand the behaviour of the ultra-wealthy is to recognise that they see themselves as uber mensch. They consider themselves above us. They are world- and history-altering demi-gods and we should worship them. The sad thing is that our economy and our governments, and even some of us regular people (just look at Elon Musk’s reply guys…) reinforce this delusion – we make it true by continuing to offer them funding, respect, and more, when all they deserve is to be treated like the villains they are. What happens to the villain at the end of the film? None of them deserve the redemption given to Phoenix. So what is left? What would make for a satisfying end to the story of these cretinous ghouls that lay waste to the world and their workers?

There’s only one answer.

Writing and/or interacting with people will be beyond me though. ↩

When I first got my depression diagnosis, the GP informed me that for most people a depression like mine would pass after six or twelve months. I’m sure he thought he was being helpful, but when the depression didn’t simply dissipate it made things worse. Not just because it seemed to prove that something was wrong with me3, but also because it left me not knowing when or how I might get beyond it. ↩

It likely took me ten years to completely get past the stigma of being depressed/needing meds to function. That sounds stupid now, but the early thousands were a different time and my diagnosis did legitimately carry stigma, even if someone of that was purely internal. ↩

You just read issue #190 of Nothing Here. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.