[brinspotting] The Niqud of the Niqud

Hi everyone! Happy almost 2026!

First things first: Chris Dickey, Yoon-Wha Roh, and Fabio Manchetti recently released an album of new works for tuba and piano, New Vantage, which contains a studio recording of the sonata I wrote for Chris back in 2021! It’s a fabulous take of my piece, and the rest of the album is full of absolute gems played with conviction and charm. The link above will take you to YouTube, but you should be able to find it on all the usual steaming platforms. Take a listen and spread the word if you’re so inclined!

Second things second: Below is a (rather long) essay on the current state of the siddur project for those who are interested. Especially as I’ve pulled back from social media, I feel like there’s been a bit of radio silence from me about where things are at and what to expect going forward, so consider this a progress report/update on how I’ve been spending my time in the ~18 months since the hard copies were released.

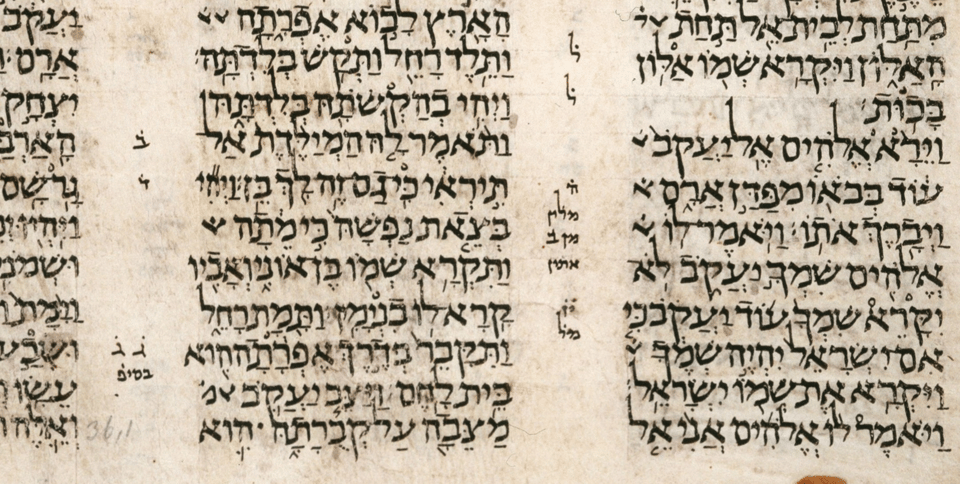

The title — “The Niqud of the Niqud” — comes from a little comment my friend ada made in a Discord server one day. Liturgical Hebrew has a bunch of little dots and squiggles, called niqud, that get added to the core consonantal text to indicate the finer points of pronunciation and synagogue recitation. These niqud follow a bunch of arcane rules, and, having spent as much time studying them as I have, I’m often able to swoop in to conversations about Hebrew grammar to explain just why this one word seems to break the expected pattern. As such, ada has taken to joking that I can be relied on to elucidate “the niqud of the niqud” — the finer points of the finer points, as it were.

This is, among everything else, an essay about what it is like to know that.

The Niqud of the Niqud

Introduction

Several years ago, back when I was in high school, a friend of mine was looking over my shoulder as I was punching some music into the computer and snarkily judging my process. My musical friend group at the time was full of braggadocious fighting about different music notation programs — any time we got together, we composers would invariably get into a pissing contest about whose preferred software was superior, the Finale users ragging on the Sibelius diehards and vice versa, with me off in a corner holding forth on the virtues of my preferred poison, LilyPond. We were insufferable in the way that teenagers, I think, are supposed to be.

But the friend looking over my shoulder wasn’t a musician, he was a computer geek, and he was aghast to see me manually entering the exact same melody in both the flutes and the violins. “In computer programming,”, he told me, “we have a very important principle: DRY — Don’t Repeat Yourself.”

I’ve still yet to wholly eliminate duplication from my compositional process, but his admonition stuck with me, and the principle — that when it comes to computers, it’s better to make one version of a thing that can be referenced multiple times down the line than it is to manually create multiple versions of the same thing for each specific time you want to use it — hovers often in the back of my mind.

Beyond a simple quest for efficiency (itself nothing to sneeze at!), the primary motivation here is consistency: If I’ve manually written out the same melody twice (once for the flutes and once for the violins), then if I want to change that melody, I have to make sure to adjust both instances of it, and it’s easy to accidentally forget one or the other. The more copies there are, the greater the chance that they get out of synch with one another, and the greater the headache if it’s been a while and you need to go back and pull an authoritative version out from the mess.

I don’t usually go back and rework melodies. By the time I’m ready to engrave them into a PDF, I’ve typically been over them dozens and dozens of times; I’ve gotten the fussing out of my system well before I even open up my laptop. But the siddur is another matter. My work there is often more exploratory: I write a version of a prayer and then I spend some time praying with it and realize it doesn’t quite flow right, or I stumble onto a new teaching that I want to work in to my translation, or I just notice there’s a typo in transliteration. Not everything’s been overhauled from the ground up, but few things are exactly as they were in the very first draft.

This is all well and good for self-contained one-off prayers. If I want to tweak the prayer for rain, there’s just one place I have to look. But many prayers show up in multiple places across the liturgy, whether as large blocks of identical text (the first half of the qadish, eg, shows up seventeen times across the combined Shabbat and Festival liturgy) or as one-line excerpts slipped into other texts (as when the blessing for Shabbat morning light quotes the opening of Psalm 92, which itself shows up wholesale elsewhere in the siddur). And so when I wanted to change one of those, I would have to do a search for other instances and manually alter each one in turn, a task at once tedious (again, seventeen qadishes!) and nerve-wracking (what if I missed one!).

This liturgical repetition isn’t always super obvious, but it’s quite common, and for all that it speeds up the work by letting me copy and paste text I’ve already wrangled, it also slows it down by forcing me to make the same update multiple times without introducing any new errors in turn. More than once, I found myself wishing that I could set up a system where I had one copy of the qadish stored in a file somewhere, and then whenever I wanted to print it, I could just insert an instruction saying “hey computer! please find the file named ‘qadish’ and print its contents here!”. (Or, for a partial quote, “please print lines 17-24” or whatever.)

But, of course, the real frustration came later. In my initial, exploratory drafting, I wrote everything up as plain text. No coding, no formatting, just a raw string of words and line breaks. This is great for dashing ideas off — think opening a blank Word document and just starting to type without adjusting any of the default settings — but it obviously isn’t the only way I published the siddur. I did, in fact, want there to be versions with formatting, whether the precise page layout of PDF (necessary to make physical copies!) or the fussy HTML tags necessary to make everything render properly on the web.

I struggle to fully convey the magnitude of the work involved in creating web and PDF versions of the initial plaintext file. But I really want you to understand it; so much of the past year’s descent into controlled madness for the sake of entirely reworking my process for the siddur has been driven by just how monumental and horrible the manual conversions were. I want you to come on this journey with me; I want you to feel, even if only briefly and at a distance, an echo of the abyss I’ve been plumbing; I want you to see why I thought this nonsense undertaking was, in fact, a reasonable thing to do.

Perhaps the best way is with an example.

Katabasis/Descent

Let’s imagine the simplest, most basic possible psalm, just one verse and two words long in the Hebrew: מִזְמוֹר לְדָוִד׃ | Mizmor ləDavid. | “A psalm of David!”. In the plaintext version, the one I started with, that would look like this:

1 מִזְמוֹר לְדָוִד׃

1 Mizmor ləDavid.

1 A Psalm of David!A file five lines long, three filled with text and two left blank for ease of reading. You can see how it would be quick to write this way!

Generating a PDF is a bit fussy at the best of times, and to get there, I use a program called LaTeX. LaTeX is a “What You See Is What You Mean” program, which essentially means that rather than directly fussing with the layout by clicking and dragging or zhuzhing things by eye the way you might in Word (aka “What You See Is What You Get”), you tell LaTeX “hey! this is a chapter heading!”, and then it formats all the chapter headings the same way.

In our case, of course, we’re more interested in telling LaTeX things like “this is a psalm” or “this text should be printed in the Hebrew font, not the English one”. Some of this can, mercifully, be abstracted away (it’s possible to tell LaTeX “here’s how I want you to format a psalm” once, up at the top, instead of having to repeat the instructions for each new psalm), but much of it has to be directly applied in each instance. Here’s what our very minimal psalm winds up looking like:

\begin{hebrewpsalm}

\begin{hebrew}מִזְמוֹר לְדָוִד׃\end{hebrew} & 1 & Mizmor ləDavid.\\

\end{hebrewpsalm}

\begin{englishpsalm}

1 & A Psalm of David! \\

\end{englishpsalm}I know that some of you will find this daunting, but I want to encourage you not to just skim over it. Really take the time to pick it apart and notice which bits of the plain text have been carried over, what has been added, and how all these things relate to one another. Don’t just take my word that all these things line up; try to hold the process in your head.

We have to do something similar to make the HTML version. Again, many of the overarching rules are abstracted away instead of being re-typed for each new psalm, but there’s an added layer of complexity here because for the web version, it’s important that users can hide or unhide various bits of the text depending on their needs, and your web browser is not smart enough to automatically distinguish transliteration from translation; it has to be told what’s what.

The HTML version of our micro-psalm looks like this:

<div class="passage">

<div class="psalm-block">

<span class="verse-num">1</span>

<div class="hebrew-block" lang="he">

<p class="hebrew-line">מִזְמוֹר לְדָוִד</p>

</div>

<div class="translit-block">

<p class="translit-line">Mizmor ləDavid.</p>

</div>

<div class="english-block">

<p class="english-line">A psalm of David!</p>

</div>

</div>

</div>Horrible, right? (I find it horrible, even with color coding to take the edge off.) Again, I encourage you not to skim over this; the code here isn’t gobbledygook, just prolix. The little class names are annoying to keep track of, but you can probably guess what "verse-num" means and what kind of text you expect to find in an "english-line" paragraph.

OK, so that’s what it takes to get our one-verse micro-psalm ready for the PDF and web versions. Now imagine doing this, by hand, for 31,639 lines of plaintext instead of 5.

I’ll wait here for you to stop screaming.

It’s possible to speed this process up with the help of editing tools that, for example, automatically close <div> blocks, but even so, the task remains a grueling slog that is absolutely brutal on the wrists.

Also, at the end of all this, 34,000 lines of LaTeX and 47,000 lines of HTML later, there’s an additional problem: Nothing is a stand-alone prayer anymore; everything now exists in triplicate. So whenever I found a typo, I’d have to fix it in at least three places, and possibly as many as 51 if — G-d forbid! — I found something that needed fixing in the ḥatzi qadish. And I would have to make all of these changes by hand, one by one, without introducing any new errors. Not ideal! Contemplating doing this entire process again for the weekday version, and then again for the Rosh haShanah maḥzor, and the Yom Kipur maḥzor, and on and on, you can perhaps understand why I was eager to find some other solution, any other solution, anything that would save my wrists from all those curly braces and angle brackets and also stop me from potentially having to fix the same error in the qadish two hundred and four or more times. Even I have my limits.

Which is how I found myself learning to code so that I could remake a siddur.

Abyss

The coding book I worked my way thru, How to Design Programs, makes a point of separating out programming knowledge from domain knowledge: As a programmer, you should know how computer programs work, but often you’re going to be writing a program meant to operate in a specific technical field, and you will need to tap an expert in that field for specific information — asking a structural engineer about the strength of various materials for a bridge-modeling program, say, or a luthier about the inner dimensions of a violin for an acoustics simulation.

Theoretically, I could be the domain expert as well as the programmer for this project. After all, I know Liturgical Hebrew reasonably well, and I certainly have more than the average experience in assembling a siddur in multiple output formats.

Still, there’s a lot to know.

There’s an anecdote I’ve seen going around social media several times over the years that, of course, I cannot track down now that I want to formally cite it. A teacher did an information-literacy unit every year where they got an expert on some topic to come into class along with a confident bullshitter and then tasked their students with telling which was which. What this person found was that their students almost always thought the bullshitters were the real deal, because they answered everything confidently and authoritatively while the real experts were constantly hedging with acknowledgements of uncertainty, limited data, divided opinions in the field, and so on.

I can’t fact-check that anecdote, nor can I speak to its statistical validity, but I can say with fervor that it matches my experience trying to know things. The truth is slippery; it writhes in your grasp like some protean sea beast — as soon as you think you have a firm hold, it wrenches free and darts off into some new cavern of ambiguous complexity. Always there are lacunae, gaps where the evidence fails and the best anyone can offer is a plausible but unsupported hypothesis to carry you over the chasms.

Take the Hebrew vowel that looks like a little colon, the shəva. Sometimes, in normative US Liturgical pronunciation, this vowel is silent, and sometimes it makes a quick, indeterminate, unstressed vowel sound that I like to transliterate with its IPA namesake, the schwa: ə. But when is it silent, and when is it pronounced?

Many pronunciation guides for liturgical Hebrew helpfully offer lists of rules to tell these two kinds of shəva apart, and many of the rules are, mercifully, consistent across sources. Everybody seems to agree, for example, that when there are two shəvas in a row, the first is silent and the second pronounced. But when you get into the finest points and most complex edge cases — the niqud of this niqud — it’s rare to find two lists that are wholly in agreement. Sometimes, this is simply a case of opting for brevity — if a shəva is the first vowel in a word, it will always be pronounced except in one specific case (שְׁתַֽיִם/shtáyim, for those playing along at home), and it’s easy to understand why an introductory overview might opt not to go into that level of granular pedantry.

Unfortunately, not all differences are so easily resolved. Liturgical Hebrew will sometimes place a little dot inside a consonant to indicate that it is emphasized or doubled. (It’s not the only thing the dot can do, and it’s not exactly doubling, but we’re so far into the weeds already, please just roll with it.) If a shəva shows up under a consonant with that kind of dot, everybody agrees that it should be pronounced. So far, so good. The definite article — the word the — in Hebrew takes the form of a prefix: ha- gets plonked on the front of the word and, in most cases, the first letter of the word gets doubled with a little dot. If there’s a shəva under that consonant, everybody agrees that that shəva should be pronounced. So, for example, if you want to say “the blessing”, that’s הַבְּרָכָה | habərakhah, with the audible shəva right there after the b where we expect it.

Under some circumstances, however, that dot disappears. Some understand this as a purely orthographic phenomenon: The consonant is still really doubled, our texts just don’t always print the helpful reminder dot. Others understand it as a genuine loss of emphasis: That missing dot accurately reflects a de-doubling of the consonant in question. In the former reading, the shəva should be pronounced; in the latter, it should be silent.

It’s worse than this, tho, because many authorities split the difference, with some of these missing dots being purely orthographic and some being a genuine loss of doubling, with the presence or absence of another small mark — the méteg, a tiny vertical line placed under many letters in our texts — indicating which is which. This would be all well and good (I guess), except the méteg is one of the most vexatious marks in Liturgical Hebrew orthography. Not only is it burdened with multiple different functions depending on its context, it is frequently deployed for no discernible reason in strange and unexpected places, leading to grammatical commentators of every generation to gnash their teeth in bewilderment.

Another thing I should probably mention about the méteg: Our best manuscripts don’t always agree about which words do and don’t have one. This is true both within a single manuscript when the same word shows up in multiple places and between manuscripts when you compare different scribes’ spelling of the same passage. Good luck!

At this point, it’s worth taking a step back. Normative US Liturgical Hebrew pronunciation is a strange beast. It’s not the same as the pronunciation used by contemporary Hebrew speakers, nor is it the same as any of the numerous pronunciation systems of historic Diaspora communities, which are themselves not the same as what was going on when Hebrew was a living language the first time around (in the era when the Biblical texts were being written), which itself famously had distinct regional variants that were all current at the same time. The shəva sound itself is quick and indistinct, and in the actual context of real-world speech, I’m doubtful that it’s always possible to tell when it is or isn’t present, just as I don’t think you can always cleanly distinguish “he is coming” from “he’s coming” in spoken English. Authoritative guides love to fulminate against the slovenly pronunciation of those not up to their standards, but my little descriptivist heart rebels at the point where they say that most American Jews systematically mispronounce vowels — if most people pronounce a certain word a certain way, then, as a matter of pure fact, that is how that word is pronounced, and a transliteration scheme meant to help those not fluent in the Hebrew writing system follow along in a service led by people pronouncing Hebrew that way (which is what my scheme is meant to do!) should reflect that. The fear here is that a mispronounced word will lead to a changed meaning of the text, which will, in the worst case, lead a naïve congregant to mis-derive halakhah and commit a sin as a result of this chain of error and illogic.

I submit that this is simply not how any of this works. Actual speech is always a squishy affair — our lips and tongues and teeth and throats jiggle and flap and click and take all kinds of shortcuts that elide some sounds and emphasize others, that flip some sounds around and spontaneously add others that are nowhere to be found on the page. We drop the first t in “hot potato” and read “comfortable” as “comfterble” (look at that r go!), and still we get our point across because the way the brain parses language is, in fact, much more complicated than just rote transcription of the sounds we hear. Also, who is this hypothetical person who is perfectly fluent in Biblical Hebrew while also totally unaware of the fixed content of Torah, concerned with halakhah while simultaneously being oblivious to the millennia of halakhic rulings that radically elaborate and reshape the bare-bones laws of the original texts? I’ve certainly never met anyone like that. Also, are there even any words whose meanings shift radically depending on the presence or absence of a brief, barely audible “uh”? Do the endless regional variants in how to pronounce pecan actually stop anyone from successfully making a pie?

Also: We know that there are typos in even our best manuscripts, and we know that many scholars have succumbed to the temptation to “correct” the niqud to match their theories rather than matching their theories to the niqud. Also: Suggesting that it’s necessary to decide between competing manuscript traditions dating back 1000+ years before you can know how to pronounce a given word is just not a serious proposal for pragmatic everyday prayer. Also: Linguistic diversity is a gift of profound beauty, and the effort to stamp out all variation for the sake of a uniform, unchanging standard feels, in a word, lousy.

In other words: It is probably impossible to create a definitive list of every single audible vs silent shəva in our liturgical texts, but also, it doesn’t matter. It’s possible to systematically follow the rules that everyone agrees on, and then make judgement calls for the edge cases. For those who would judge those calls differently, I can think of no better rejoinder than this sublime aside in a footnote on page xviii of the 2003 JPS Tanakh: “We . . . trust that those for whom such errors matter have the wherewithal to determine a reading that will satisfy them.”

Anabasis/Ascent

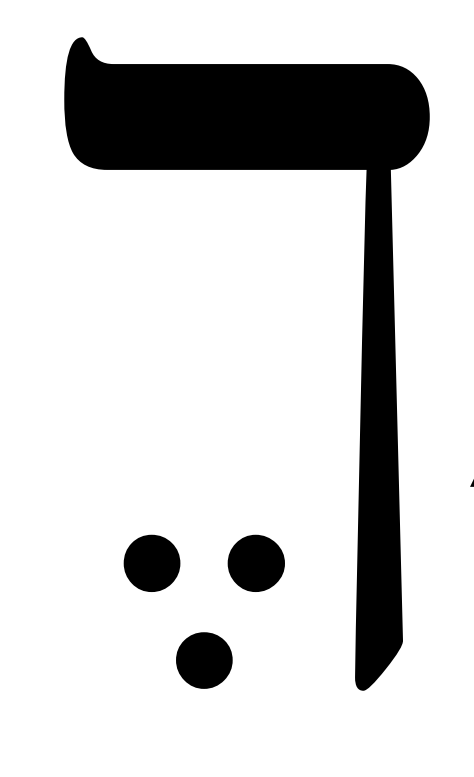

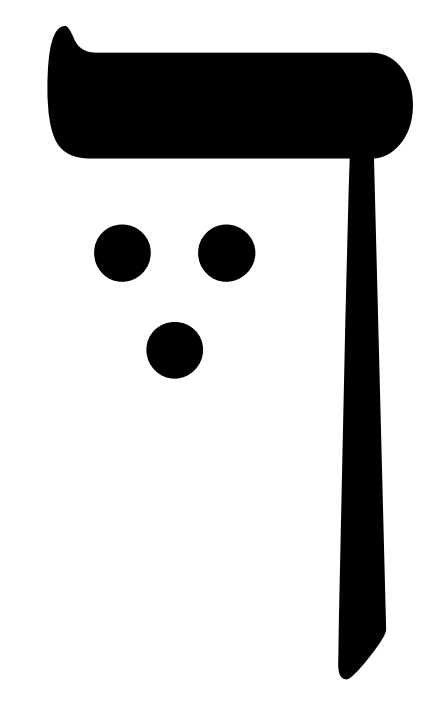

The above is just one of the many boondoggles I fell into in the past eighteen months. Some of them didn’t even have anything to do with coding; they were just by-products of stripping the project down to the studs and starting anew. It seemed like a good opportunity, for example, to tweak the Hebrew font I’m using to more gracefully accommodate the siddur’s nonbinary endings — editing the interface between the “kh” consonant and the “e” vowel in the second-person ending “khe”, for example, so that the vowel gets tucked up under the consonant the way it does for the vowels used for the masculine and feminine versions.

Here’s what the old version looked like:

And here’s what I wanted it to look like:

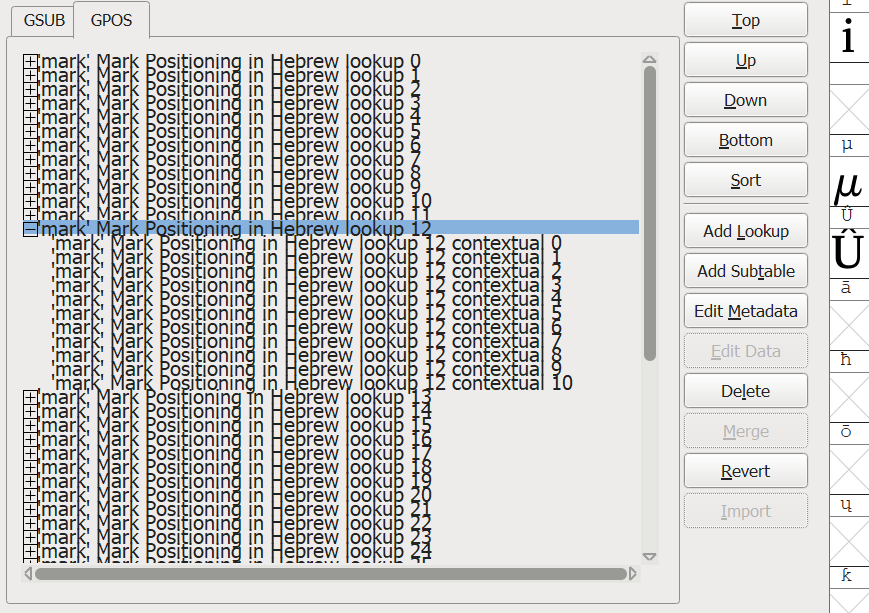

There are two things that make this tricky. The first is that Unicode’s Hebrew implementation is sub-optimal in a number of ways, not the least of which is that the codepoints for two of the cantillation marks are misnamed — the point for zarqa behaves like tzinorit and vice versa. The second is that the way that Biblical Hebrew fonts assemble composite characters is a little fussy. Because fully assembled Hebrew characters can have so many layers — consonant plus doubling dot plus vowel plus cantillation mark — it’s impractical to have a pre-made symbol for each combination. Instead, each individual component — the bare consonant, for example, or the symbol for the vowel alone — has, on the backend of the font, a whole constellation of anchor points: preset coordinates that tell a typesetting program where to put the symbol relative to other symbols.

So a vowel that should be centered under a consonant might have an anchor point meant for wide consonants and another for skinny consonants, while consonants would have an anchor point for vowels that should be centered under them and another for vowels that should be nudged a little to the side. To build a full character comprising a wide consonant with a vowel centered underneath it, the font can then match the “wide consonant” anchor point of a vowel to the “centered vowel” point of the consonants, and the two symbols will then appear in the correct position relative to one another.

In theory, if you want to tweak the behavior of two symbols, you just have to find (or make) the pertinent anchor points and then adjust the rule that controls when and how they line up. But there are a lot of symbols, and a lot of ways for them to combine, especially when you get into scenarios where you do have four or five symbols going into a single final character, and this means that there are a lot of tables telling the typesetting software how to line everything up. Also, instead of being named descriptively, these things all have names like “Anchor 47” and “‘mark’ Mark Positioning in Hebrew lookup 12 contextual 10”. Helpful!

Ultimately, to make any headway here, I had to manually write out a list of what each of these did by opening up each one individually and describing what I found inside. But in the end, I did do it. And I also resurrected an obscure cantillation mark that has been sidelined by the carelessness of certain editors, just because it was there, and I could. The abyss is a horrible place, but there are strange wonders there for the finding.

All of this, of course, is before I even got to the core of the work of coding the siddur, creating the complex set of functions that take in a single set of lines in an input file and spit out the perfectly formatted plaintext, HTML, and PDF versions we spent so much time with above.

I don’t know how much I have to say about that work. It was challenging, and at times frustrating, but I don’t know that it’s particularly interesting in itself. It mostly involved sitting at my computer, staring at a blinking cursor after getting an error message or some hideous garbled output and trying to think with a frankly brutal level of rigor about exactly what the correct order of computational steps was and exactly where I could deploy clever shortcuts to speed everything up. As with writing prose, the bulk of the work is getting your thoughts clear, not typing.

The joy I felt when I cleared a major hurdle — automatic line numbering in the plaintext version, correct page breaks in the PDF — is difficult for me to put into words. It is a feeling of quiet elation, of radiant triumph and relaxed self-assurance. It is one of the greatest feelings I have ever felt. Taking the subway, I’m barraged by ads for generative AI companies that promise to automate away this work and, consequently, this feeling, too. Having built a thing like this, I cannot take those ads as anything other than a mortal threat.

At the Surface?

I am almost out of the abyss. At this point, I have a working prototype, a satisfactory proof of concept. There are still a number of functions to write that I’ll need for the final version of the whole siddur, but there’s no doubt in my mind I can write them — once you have a function that works to create a subsection, it’s a much simpler matter to add a subsubsection. That’s the sort of fleshing-out work that remains.

The professional computer people in the audience will doubtless find the results messy and amateurish. I make no claims to coding brilliance here; my only assertion is of pure brute functionality. After all, it’s not like I went off and earned an entire computer science degree. I worked my way thru one (1) introductory-level textbook, skipping the exercises that didn’t feel like they applied, and called it a day. By many metrics, what I’ve built is very rudimentary.

But, of course, rudimentary is relative. I have a vision of a very horizontally organized Judaism, a Judaism where everyday members of the congregation have the skills and knowledge to play an active role in shaping their ritual lives. That’s part of why I included a whole appendix on nonbinary Hebrew in the siddur: I want to give people the tools to build their own versions of this work; I want people to feel empowered to make their own experiments with degendered liturgy and other genderweird Hebrew projects. And it’s why the source code for every version of the siddur has always been public domain — if what I’ve done seems like a useful jumping off point, I want people to be able to muck around in the innards and refashion it into something more tailored to their circumstances, their needs.

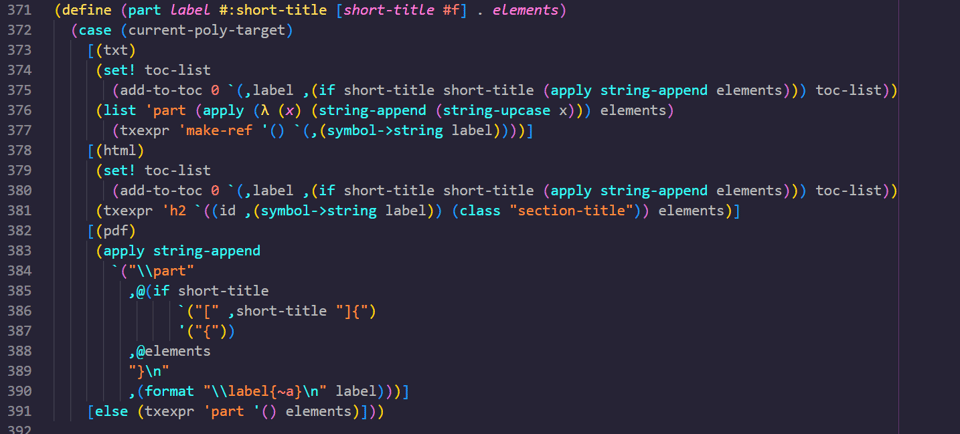

Redoing the entire thing in Racket/Pollen feels, in some ways, like a betrayal of this vision. I mean, just look at this:

This is the code for adding a part-level section title to the siddur, one of the simpler operations that the code has to handle. Those of you with some coding experience may be able to parse this with little difficulty, but let’s not fool ourselves into having a feldspar moment: I’m under no illusions that the average person off the street wouldn’t find this not only incomprehensible, but prohibitively daunting. Having the project rely on code like this is a major barrier to other people being able to pick it up and run with it.

And yet: I probably shouldn’t kid myself. Even in its initial iteration, the siddur has always been a fiendishly technical project, relying on a base of deep knowledge that is just not very widespread. The most common kind of communication I get related to this project is people reaching out to ask for help re-working a blessing into nonbinary Hebrew. Shockingly, not a lot of people are actually super fluent in constructing new passages of Liturgical Hebrew!

So the barrier for entry here was already quite high. This new version certainly raises it, but perhaps not by all that much, in the end. To use another musical analogy: There are some bassoon pieces, like Johann Ernst Galliard’s six sonatas, that are relatively undemanding, well within the ambit of a beginning student in their first year or so of lessons. There are other bassoon pieces, like Luciano Berio’s Sequenza XII, that even seasoned professional players find nightmarishly difficult. Most people, obviously, cannot play the bassoon, and so cannot play any of these pieces. But for most people, “getting good enough to play Galliard’s sonatas” is an eminently reasonable goal when setting out to study the instrument, while “getting good enough to play Sequenza XII” may not be. (I was certainly never good enough to attempt it, even at the peak of my abilities.)

My hope is that the code for the siddur is more like Galliard than Berio. If you don’t know from computers at all, sure, it’s impenetrable. But it’s not the sort of rats’ nest that only the most brilliant in the field can make sense of; it’s something that anyone can have a reasonable hope of understanding with an introductory level of study. It’s a bar to clear, to be sure, but perhaps not as high as it could be.

Again, that’s my hope. I’m not sure I’ll ever really be able to put it to the test. If you’re a computer person™ and want to take a peek at what I’ve done and offer suggestions, feel free to reach out. As with the rest of my work on this project, I make no claims of intellectual ownership of this code, and am excited to show my work.

Sailing Away

This has been a long newsletter. Buttondown is probably going to yell at me for writing this many words without putting in a “subscribe” button, so here, hi, if you aren’t already subscribed and have somehow read all this way, you can sign up to get more words from me here:

The e-mails I send are not frequent, and they are mercifully not all this long.

Why write all this?

An idea is an insubstantial thing, almost weightless. Almost, but not quite: Pile enough ideas up in a heap and they take on a heft, a mass, a pressure that will not be denied.

I sometimes find it difficult to talk to people about the siddur. Not because I don’t stand behind it as a project, but because, as a project, it’s almost too large. It sprawls out in too many directions; there’s too much of it to hold in my head all at once. How can I convey this thing to others when I struggle to understand it fully myself?

When I write music, it often feels like I am channeling the notes from somewhere Else, my brain a radio antenna tuned to a parallel dimension. Starting a new piece is often a little fraught, but as I get further into it, there often comes a tipping point after which it is very difficult to stop writing (to eat, to sleep, to trundle off to my day job,…). Imagine, if you will, a massive dam holding back a mighty reservoir. The smallest of fissures opens up somewhere in the middle, and a tiny jet of liquid forces its way thru. Not much at first! At first just a trickle that really has to fight its way thru the cement. But as it goes, it eats away at the passage, opening it wider so that more water flows thru and more and more; the pressure becomes too much, and the whole thing bursts asunder. My mind does not burst like a ruined dam, but I feel that unbearable pressure all the same, the sheer weight of all those ideas, piled up, writhing to be released out into the world. When I add the final barline, I often experience a strange sort of emptiness, like a canyon hollowed out by a torrent that has since dried up.

This project is that experience cubed. The weight of the siddur, conceptually, is overwhelming. The mass of its accumulated notions is almost too much to bear. Trying to hold it all in my mind at once is like being concatenated with a planet.

I don’t need everyone to understand all the specific little subroutines of the code that I put together for this. It’s fun, and talking shop about it would be nice, but that’s not why I’m vomiting forth all this verbiage. The impetus is to try, to desperately try, to share the mass of it all, to peel back the screens and lay bare the frenzied expanse of the work, to take your hand and pull you into the abyss with me so that we can find our way back out together and then, safely back on stable ground, reassure each other that the plunge was real and not a figment of overheated imagination. To be, perhaps, just slightly less alone in this profoundly solitary endeavor.

Thank you for dipping into the depths with me. There are so many things down here that glow fantastically in the dark. Maybe one day we will both be among their number.

I don’t know when the next official release is going to be, exactly. Maybe over the summer, if things don’t get too derailed by the exigencies of life. G-d willing, things will go faster after that, but as ever, I make no promises here; I just express hope.

I hope I have the time to finish everything I have planned. I hope others come and run with my work in all sorts of other directions. I hope we build, collectively, all together, a world that is beautiful and just and good. I hope one day we manage to pull ourselves out of the abyss.

Thank you for reading all this way down to the end. If you’d like to support this work, you can chip in at the world’s most unrewarding Patreon or just send me a one-off tip over at PayPal. The next couple of months are likely to be rough financially (interstate move, complicated job changeover situations, suddenly car insurance), and every little bit really does help.

Also, in non-financial ways to chip in: I’ve been working my way thru the big box set of Steve Reich recordings as I noodled around with the prototype code, but there’s no way those albums are going to be enough to get me thru the entire siddur. What omnibus collection should I move onto next? Feel free to throw any and every kind of box set (or artist whose complete discography is relatively easy to work thru in chronological order) my way!