Foz Meadows' FINDING ECHOES – Excerpt and chat

Hey, friends! I'm sick again (fourth time in two months, ugh) so I was thrilled (read: blearily excited between coughing fits) when Neon Hemlock asked if I'd like to feature Foz Meadows's new novella Finding Echoes in my next newsletter. Read on for a quick Q&A with Foz followed by an excerpt of the book.

Quick announcements from me:

I'll be teaching my 4-week horror writing class again starting February 11 – please share the link with anyone who might be interested!

My last newsletter was a cover reveal for my upcoming horror novel Dead Girls Don't Dream. Preorders are now open wherever books are sold, but if you order through Astoria Bookshop you can get a signed/personalized/doodled on copy.

If you are looking for ways to help the Palestinian people as they survive genocidal violence, you can donate e-sims, scream into the moral void that is your elected official, or connect to organizations trying to help. (h/t to Sarah Gailey for the last link.)

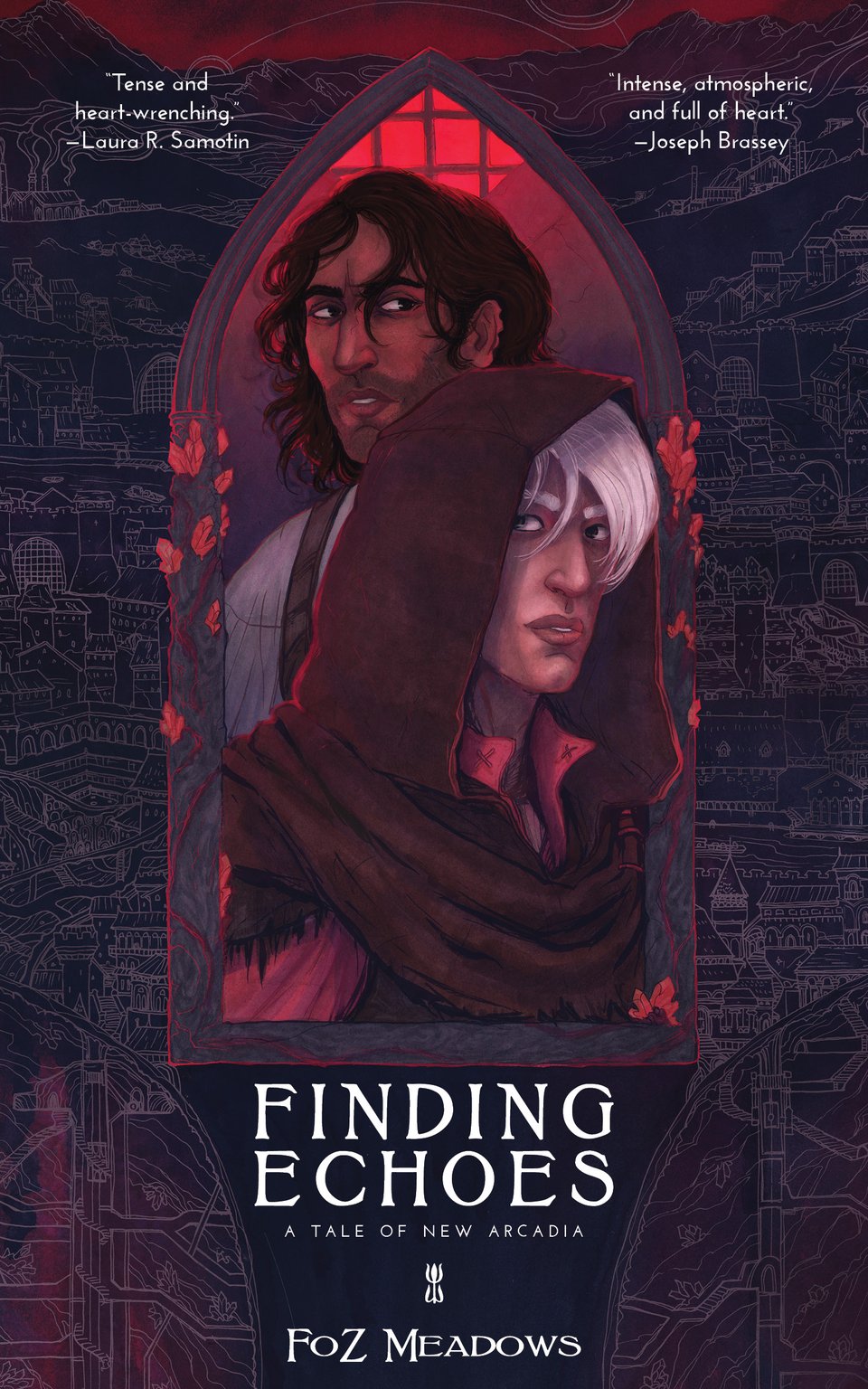

Foz Meadows is a queer fantasy author, essayist, reviewer and poet. They are a four-time Hugo Award nominee for Best Fan Writer, which they won in 2019. Their most recent novel, A Strange and Stubborn Endurance, is a queer romantic fantasy published by Tor; the sequel, All the Hidden Paths, was released in December 2023.

Finding Echoes releases today, 1/30, and is available wherever books are sold.

Snow Kidama speaks to ghosts amongst the local gangs of Charybdis Precinct, isolated from the rest of New Arcadia by the city’s ancient walls. But when his old lover, Gem—a man he thought dead—shows up in need of his services, Snow is forced to reevaluate everything. Snow and Gem must navigate not only a city on the edge of collapse, but also their feelings for each other.

What's the heart of this book? The thing that made you write it?

FM: It's a story about perseverance in the face of grief, where grief comes as much from the impersonal cruelties of a bigoted system and the choices we make to survive it as it does from personal loss. There's also resistance, too, of varying forms and against various things, but you can't resist grief; you can only persevere in the face of it, I think, and that takes love, which is also a kind of hope. It's about that, and ghosts, and drugs, and your ex coming back from the dead to ask you to help save the city that's abandoned you both. Queer shit.

Most mysteries start with a dead body and a question of who killed them. Since your protagonist can just ask the dead how they got that way, what drives this story instead?

FM: In order to question the dead, you first have to find them - but at the outset, the characters aren't even sure if the person they're looking for is dead. This makes the story, you could argue, not so much a whodunnit as an ifdunnit, or possibly a wheredunnit, merging ultimately into a whydunnit (as all whodunnits must, to some extent). But I also like the idea that, while the dead can't lie, they're not oracles, either: they can't report in death a thing they didn't know in life, and there's a time limit on how long their echoes linger for questioning. It's just a different set of rules whose implications change what can be known, and when, and under what auspices: you gain one ability, but it's not a panacea, and it comes with its own restrictions. It reminds me of how, when mobile phones first started to become commonplace, some TV writers complained that Seinfeld-style sitcom plots were unworkable now, because you can't have miscommunication when everyone is constant contact - except, as we all now know from experience, you absolutely can; it just unfolds in different ways. This is like that, but with murder.

Something I still struggle with (and have fielded a lot of questions about from writing students) is about knowing when an idea is a novel, novella, or short story. As someone who's written all three, can you talk about how you navigate the constraints or expectations in each? How did Finding Echoes find its shape as a novella?

FM: The world of New Arcadia is one I started building a frankly embarrassing number of years ago, its details accreting through multiple failed attempts at telling the wrong sort of story until, at long last, I stumbled on the right one. I'd like to be able to offer some insightful, reliable formula into the process of telling short from novella from novel, but nothing I write is ever really planned in terms of length. I get an idea, I turn it over in my head, I start writing, and at a certain point - perhaps two pages in, or two chapters, or longer than that - a sort of arcane intuition tells me how long it will be, which is more like an estimation of propulsion than distance. I'm not looking at an endpoint and working backwards so much as marking the trajectory of a ball in flight and gauging how much further it will go before it falls, if that makes sense, which means I have to throw the thing (i.e. start writing) in order to make the estimate at all. Asking where it might land before then is pointless: I know how far I'm theoretically capable of throwing a ball, and I can of course put more or less strength into my throw - more height, or more torque of the wrist - but the deciding factor is the size and weight of the ball itself, which in this metaphor remains largely opaque until the attempt is made. The story picks its own length, and we take the credit for it.

The dead boy’s umbra is three days faint, shot through with red and black. It crouches in the cramped and cluttered corner of this cramped and cluttered rookery, waiting for time or a vox like me to bring it some semblance of peace. Unlike the boy himself, the umbra bears no signs of violence, no cuts or blood or bruising. Its face is clear, its clothes as neat as they ever were in life. The Kithans would have me believe that what I see here is the soul of the boy whose body lies shrouded and cold three rooms away, poor minnow, but I don’t believe that. People lie, but umbras can’t: they’re shadows of the dead, not the dead themselves. The umbra whimpers: a high, thin note that I alone can hear.

“Mikas?” I say, kneeling. “Mikas, can you speak?”

Behind me, Rahina stifles a sob. “You see him, Snow? You see my boy?”

“I see him.”

The umbra turns its ghostly head and looks at me with wide, unseeing eyes.

“Who killed you, Mikas?” I ask it—gently, for Rahina’s sake. “How did you die?”

Uncle Tavo hit me, says the umbra. He hit me and hit me. I fell down the stairs, and I stopped.

I wince. I’d guessed as much, but there’s no joy in hearing it proven. I want to know why Tavo did it, but Mikas was too young for questions about adult motives. Instead I ask, “Was he angry?”

The umbra nods. Really very.

“Do you know why he was angry?”

Another nod. The umbra shivers like horseflesh twitching away a fly, which means I’ve little time left. This long unfound, I’m lucky to get anything at all.

I spilled his quartz, the umbra says, hunched up with remembered fear. I didn’t mean to. I’m sorry.

My throat tightens. “Don’t be sorry, Mikas. It’s not your fault.”

The umbra looks at me, opens its mouth, and dissolves in a shudder of static. Blown away like a dandelion blossom of stars and silence.

“Well?” says Rahina, voice trembling. “What did he say?”

I don’t want to tell her. She won’t want to hear it. But she asked me here for a purpose, and so I must. When I stand, I look her in the eye. She’s shorter than me, though I’m hardly tall: Charybdis-born, the both of us, as underfed and undergrown as Mikas was.

“Your brother did it,” I say. “Mikas spilled his quartz, and Tavo knocked him down the stairs in a rage.”

Rahina shudders, grabs the wall and keens with grief. I brace her shoulder and she falls against me, thin bones pressing hard under skinny muscle.

“I took him in to spare him the mines,” she wails. “And he does this?”

There’s lots of things I could try to say, but none of them would help. Ever since the Assembly ruled quartz use a crime in New Arcadia, it’s even less safe for addicts to get help. Most aren’t violent—quartz brings pleasure and dreamy stillness, not the sparkling energy of starbright—but from the little I know of Tavo, he’s always tended to anger. Maybe that’s what drew him to quartz, before choice became need: to escape his own actions. The sad truth is that addicts always have reasons, but regardless of what they are, Charybdis Precinct is full of their ghosts and the ghosts of those caught between drug and user—far too many for just one vox to dispel. But I do my best. I try, though I have no temple-training; no comforting lies about souls and ascendance to offer those left with grief.

I have only the truth of the dead, and the will to speak it.

Rahina cries, and I hold her. The room in which we stand is one of two her family rents, squalid and small and three doors over from where she lives with her husband, her two remaining children, and Tavo. This room belongs to her sister-in-law, with whose children Mikas often played. Right now, they’re out roaming while their mother works—too young yet to be junza-jakes, but old enough to recognise what their future holds—but their absence didn’t matter to Mikas’s umbra. In death, his shadow knew only that this room, where a living boy once joked and laughed, was a place of safety, and so here it came.

Umbras can tell me how their bodies died, but they don’t always know they’re dead. Murder victims especially, those who die in pain and fear, are prone to fleeing their corpses, trying vainly to hide from what’s already killed them. It makes it harder to bring them justice, assuming there’s some to be had, but the dead don’t know that, and telling them changes nothing. If I were a shield of the city or a proper Kithan acolyte, as most voxes are, I’d carry a lancet and coil to record the umbra’s final testimony in a form Rahina could see and hear.

Had she coin, she might even purchase a lyracite shard to hold a soundless image of her dead son, copied from my lancet’s record. But this is Charybdis Precinct. Even a shard of lyracite is too lofty for someone like Rahina, while the wealth contained in a lancet and coil, if I ever acquired such tools, would paint a target on my back, regardless of junza politics. Instead, I trust that I am trusted to speak the truth, regardless of what it might cost me.

Regardless of what it costs the ones I tell.

Rahina doesn’t call me a liar, doesn’t ask me if I’m sure. She cries herself out against my shoulder, and when she pulls away to lead me from her sister-in-law’s room, back to the rookery hall and into her own space, she does so in horrible silence.

Inside, we find Tavo right where we left him, skyed to the nines in the only available chair. Quartz has winnowed his big frame down to bone and sinew, leeching the natural colour from his hair, skin, eyes. Once, he was as brown as Rahina, good Deyosi stock; now his skin is mottled the strange, shiny grey of lead, his hair an unnatural white.

My hair is white, too, and the fingers of my left hand look dipped in silver, though I’ve never taken so much as a pinch of quartz. But my mother did, whoever she was, and her usage claimed me as her name never has. If Tavo ever weans himself clean, his natural colouring will likely revert, but my white-and-grey is permanent. At least the rest of me looks reasonably healthy, my skin a golden brown that’s something other than Deyosi, or maybe a mix of somethings, if I guess by the mossy threads in my dark brown eyes, their single lids; the lack of curl to my hair. I don’t know what I am, but I know what Tavo is.

He’s not coming back from this.

Rahina stares in hopeless grief at her dead son’s body, laid on the rickety table beneath a thin, patched sheet. She looks at her brother, twitching in his quartz-dreams, as oblivious to our presence as he is to his nephew’s corpse.

“If I killed him for this,” she asks, softly, “would you judge me?”

Perhaps I should wish that my answer was yes, but I’ve never been that noble. “No,” I tell her.

Her fists clench. Almost, she looks like she’s ready to act on it, here and now—and then she slumps, her shoulders bowing forward.

“I’ve no scrape to pay for burial,” she says, looking back at Mikas, “and not the arms to carry him to the temple. Not alone.”

She doesn’t ask, but I answer anyway.

I help her lift her son.