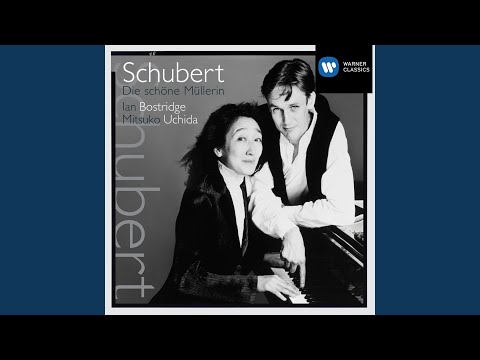

Die schöne Müllerin

Throughout the winter and early spring, I spent a lot of time listening to Schubert’s song cycle Die schöne Müllerin while I walked around the park, washed the dishes, and did other basic tasks during that gray and seemingly interminable time. The song cycle is about, among other things, pathological obsession, and I became (not for the first time) a little obsessed with it in turn.

Die schöne Müllerin is a setting of twenty poems from a collection by Wilhelm Müller of the same name, about a miller’s apprentice who falls in love with the miller’s daughter, and is driven to despair and suicide after she rejects him. But complications arise even when attempting to describe the basic events of the narrative. For instance, here’s how Arnold Feil, a musicologist, summarized the events:

A young, blond mill hand […], following the brook as he travels, comes to a mill, where he asks for work and is hired by the master. He falls in love with the miller’s daughter and wins her, but she is fickle and later bestows her favors on the hunter. Broken-hearted, the miller lad seeks death in the brook.

This summary (representative of many similar interpretations) gets at what I find interesting about the song cycle, because it’s roughly accurate but completely misses the point. In all but the last two poems, the only poetic speaker is the young miller himself, giving his own account of events, and it’s not hard to notice that his love is probably one-sided obsession completely insulated from reality. The miller-maid barely appears at all, and the only words she speaks to him are dismissive. Still, the miller continues to believe that he has “won” her until the arrival of the hunter decisively shatters the delusion.

I’m reading Susan Youens’s two books about Die schöne Müllerin (one of which is a short, out-of-print, stupidly expensive, but very valuable Cambridge Music Handbook), and she points out what others have missed: The poems’ characters—the virile hunter, the lusty miller-maid, the inexperienced apprentice—and its setting are familiar from folklore, and it’s easy to mistake the cycle for simple folk-like pastiche, similar to what some of Müller’s Romantic predecessors produced. But Die schöne Müllerin is psychodrama; it deconstructs those archetypes. Schubert was able to recognize the darkness at the heart of these poems, even though later readers and listeners would sometimes fail to do so.

The second half of the song cycle is about the miller’s self-deception and nagging sense of doubt, and, later, his envy and utter despair. This is when the cycle really shines; Schubert wrote some of the most sublime music about those emotional states that I have ever heard. “Eifersucht und Stolz” (“Jealousy and Pride”), not necessarily my favorite song but the one I find most chilling, is less than two minutes of pure seething psychosexual turmoil, wherein the miller rages about his former “nice girl” giving herself up to the hunter. It is addressed to the brook as an intermediary, as though the miller cannot even face the versions of the miller-maid and the hunter that he continually addresses in his mind. Schubert’s setting isolates the words “kehr um” (turn back) and “sag ihr” (tell her) and insistently repeats them, as though the brook could turn back time and change the girl’s mind, though we know that that it cannot.

Wohin so schnell, so kraus und wild, mein lieber Bach?

Eilst du voll Zorn dem frechen Bruder Jäger nach?

Kehr’ um, kehr’ um, und schilt erst deine Müllerin

Für ihren leichten, losen, kleinen Flattersinn.

Sahst du sie gestern abend nicht am Tore stehn,

Mit langem Halse nach der grossen Strasse sehn?

Wenn von dem Fang der Jäger lustig zieht nach Haus,

Da steckt kein sittsam Kind den Kopf zum Fenster ’naus.

Geh’, Bächlein, hin und sag’ ihr das, doch sag’ ihr nicht,

Hörst du, kein Wort, von meinem traurigen Gesicht;

Sag’ ihr: Er schnitzt bei mir sich eine Pfeif’ aus Rohr,

Und bläst den Kindern schöne Tänz’ und Lieder vor.Whither so fast, so ruffled and fierce, my beloved brook?

Do you hurry full of anger after our insolent huntsman friend?

Turn back, and first reproach your maid of the mill

for her frivolous, wanton inconstancy.

Did you not see her standing by the gate last night,

craning her neck as she looked towards the high road?

When the huntsman returns home merrily after the kill

a nice girl does not put her head out of the window.

Go, brook, and tell her this; but breathe not a word –

do you hear? – about my unhappy face;

tell her: he has cut himself a reed pipe on my banks,

and is piping pretty songs and dances for the children. (translation)

Ultimately, what I find most poignant about Die schöne Müllerin is the utter isolation of the miller, even in a world full of other people. The miller’s obsession is essentially narcissistic, and has little to do with the miller-maid and everything to do with the idea of her in his mind, as obsession often goes; she is first a perfect domestic creature, a projection of his own fantasies, and then a wicked betrayer. Even nature can do no more than reflect his own preoccupations: He initially believes that the brook has led him to the miller-maid, and he dreams of carving his love into every tree and wishing that the birds and flowers themselves would declare it. Later, he curses the entire green world outside, the domain of the hunter, and thinks of weeping so much that it turns the grass white. The only time we see him alone with the miller-maid, he finds that he cannot speak, and cannot even look at her. Tellingly, he can only look at her reflected image in the brook.

Die schöne Müllerin has much in common with Tristan und Isolde, which also partially owes its existence to the German Romantics’ revival of medieval literature. Tristan, too, has its own singular logic that requires nothing less than total surrender from the listener. You have to believe, throughout the course of its four hours, that there is no possible consummation other than death for the lovers, and the music makes you believe it. But compared to Tristan’s and Isolde’s love, cosmic in scale and transcending life itself, the obsession of the miller of Die schöne Müllerin seems petty in comparison, grotesquely magnified in his mind until it destroys him.

What Die schöne Müllerin does is capture a fantasy that is more tempting for being more ordinary. The fantasy, both compelling and repellent, is that if you become too obsessed with something or someone, you could actually behave like the miller: not by dying, per se, but by rejecting the perpetual turning of the millstones, the drudgery of going on with work and life, and instead simply refusing to move on, lying still in the brook even as the water continues to flow over you. (Even the narrator of Winterreise walks away from the linden tree tempting him to rest forever, but in Die schöne Müllerin there is no such possibility.)

Seeking variety, I spent some time listening to arrangements of this piece for voice and guitar, which I found illuminating. In “Pause,” it is revealed that the miller is not only a miller, but also a poet with a lute. In that song, he hangs his lute on the wall, wondering how his joy could ever be expressed in song. He has something of Müller and Schubert in him. (I’ve always thought that the final song in the cycle, “Des Baches Wiegenlied,” could be the miller’s final song to the world, written from the perspective of the brook.) In the recordings I listened to, the guitar, taking the place of the lute, further blurs the boundaries between the poetic persona, the poet, the composer, and the performer.

This sense of permeability accords with how I feel about Die schöne Müllerin, after years of continually returning to it. As someone who is constantly obsessed with something or other to no good end, I see myself in the songs, too, like the miller seeing his own rippled reflection in the brook. Of course, the passage of time eventually ceases for the miller; he never passes from inexperience to adulthood, but rather returns to the womb-like embrace of the brook, which is one sense in which the songs form a cycle. But since I first heard Die schöne Müllerin, I’ve grown older and changed; it’s not the same “I” revisiting the miller at the brook each time, and insofar that music fundamentally involves the listener, the music I hear has changed, too. Through the years, it’s been a gift to be able to return to these songs, both constant and ever-changing like the dark, rushing brook itself, the miller’s mysterious and unsettling companion that both listens and speaks.