The Ghosts That Haunt Me: Reading Torrey Peters' The Masker Ten Years Later

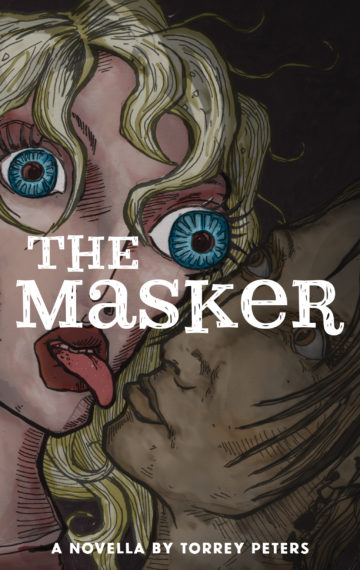

When Torrey Peters first burst onto the scene it was like a breath of fresh air. It was about a decade ago with her novella The Masker, and its grotesque mix of sex and sin and the way pronouns slid and shifted. It was dark and it was messy. I had been reading Nevada a lot at the time, flipping into it like the Virgillian Lots or something, and while Maria was a mess she wasn’t messy. If that makes sense.

The scene then was a bit of an odd one. I was figuring my shit out on Tumblr and Twitter, two of the healthiest places on the internet to do that, and working a job I really hated. I started at one pm, finished at ten, and had no social life to speak of. I would go to work, go home and browse the internet until one or two in the morning, go to sleep and do it again the next day. Sometime around then I started having really bad anxiety as I struggled more and more to rationalize away wanting to be a girl; I started taking a SSRI and got my cat Tucker.

It was a different time, I guess, but also very much the same as it is now. I remember taking sides when Topside Press went down - I still have a galley for the original printing of Meanwhile Elsewhere - and hoped like heck that Imogen Binnie would publish We See Through You, a book of Maximumrockandroll essays that never materialized. I got into stupid arguments online and listened to Casey Plett talk to Merritt K on Woodland Secrets, never once imagining that I’d have lunch with Ms. Plett a few years later - and that she knew who I was!

But the main thing I remember is that I reviewed The Masker for my blog, and then reviewed Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones for Live in Limbo. I liked it, and felt good that I was able to spread the gospel about it, as it were. And then my review hit Trans Twitter: “Why is a cis man reviewing this?” “Who told cis people about Torrey?” “They should have let a trans person write about her instead.”

I wanted to tell them something, wanted to explain it away. I remember reading those replies while standing in the lobby of the Eaton Centre in downtown Toronto, trying to explain to my friend Jenn why I’d gone so pale and why my hands were shaking. And Ms. Peters, I can’t imagine she had any idea who I was, let alone that I was a closet case who bought dresses from Old Navy online and wore them once or twice and then felt so bad I threw them out and cried. Because nobody did. To my friends I was a weird loner that watched a lot of baseball and basketball, going to Raptor games because they were cheap and seemed to follow a lot of trans people online.

Re-reading the two novellas in Stag Dance brought it all back for me: that feeling of helplessness and of release in her fiction. Of the idea that here was this punkish woman writing fiction that was challenging and different. She didn’t write for a cis audience, she didn’t even write for the polite trans audience who wanted like, I dunno, another cheerful story about women who held hands and kissed under the bleachers. She wrote with energy and verve, not to mention a sly sense of humor. And she published it all herself. I respected the hell out of that.

Peters is a writer that a certain kind of reader takes to heart and gets a touch too personal about. I’ve had arguments where I said I thought her characters were a touch too mean and that people would read too much into her life as inspiration for her fiction. For this, someone with a big account told everyone that I didn’t know how to read and I had to deal with a bunch of bullshit from that. It stressed me out so much I developed Bell’s Palsy, freezing one side of my face for like a month.

Her new book brings some of that back, too. But I know I have to let it go, to let go of so many grievances and bad memories that I cling to sometimes and hope they have some kind of meaning. That maybe I define myself in the negative - that I am not who someone says I am. But that’s a stupid way to look at things and it brings me away from my point here - that literature can save a life and people can draw their own purpose from mere words on a page.

I was a mess when I read The Masker all those years ago and I’m still a mess now. But here’s the thing: I never let myself imagine I could have the kind of mess I have now back then. Maria Griffiths was a fun ideal, in some ways, and I could see myself as the person in Ms. Plett’s story about buying socks and a dress at Old Navy, but neither one felt like they struggled the way Krys did in The Masker. There’s a lot about Peters’s fiction that can be written about, a lot that I want to write about: her effortless sense of literary style, the way she crafts distinctive voices in her fiction, the way class divides her characters. Maybe someday I will. But for now a simple plea: get yourself a copy of Stag Dance.