1994: a compendium of albums turning 30 in 2024 (part 2)

a collaborative effort celebrating the albums of 1994

Welcome back for Part 2 of this project. You can read part 1 and the introduction here.

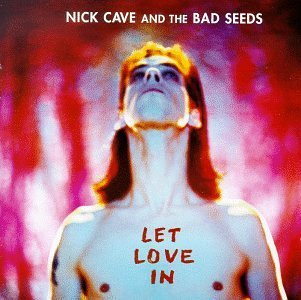

Today we first have Hunter Felt writing about a favorite Nick Cave album.

I didn’t hear my favorite album of 1994 until 1999 when I finally reached college. In my defense, I was 13 years old and trapped in Naples, Florida. Often, my friends and I could only determine which new punk bands were any good by the names our destined-for-fame rocker friend would write with whiteout on her backpack (which was the custom of the time).

So beyond “Where The Wild Flowers Grow” and “There Is A Light” (from the perfect “Batman Forever” soundtrack), I knew about Nick Cave but never actually heard him. At least, not until college when my new friends introduced me to “Let Love In" at the same time I was discovering alcohol and other things. Perfect timing.

“Let Love In” might not be the greatest album credited to Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds. The elegiac “The Boatman’s Call," the painfully personal “Skeleton Tree" or the sprawling “Abattoir Blues/The Lyre of Orpheus” might all have better claims on that title. You could probably make a case for any of their releases as a career high point.

“Let Love In,” for me, is a perfect album because it’s really a “Greatest Hits” album. Its strength lies in its apparent weaknesses: the sudden tonal shift between the perfect ballad “Nobody’s Baby Now” (the song that hooked me and still my favorite Cave composition) and the unhinged garage stomper “Loverman.” “Red Right Hand” is a moody, song about a serial killer piece that has appeared on a hundred horror soundtracks, yet it's followed by the seemingly sincere title track. Just to prove his versatility, Cave opens and closes with two radically different versions of the same song, “Do You Love Me?" I still can't decide which I prefer.

Maybe it’s only my favorite because it was my first Cave album, the one I’ve been listening to for over two decades straight now. Maybe. I don’t think so. Every song here is a gateway to another Cave album and, for me, it’s like hearing his entire catalog in a single sitting. Considering the greatness of that catalog, that’s a high compliment.

There you go, my favorite album of 1994 doesn’t remind me of 1994 at all. In fact, it feels completely of its own time rather than a gateway into the past or the future. Maybe that wasn’t the point of the exercise, maybe I should have gone with R.E.M’s “Monster, Gravediggaz’s “6 Feet Deep” or Pavement’s “Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain,” all of which transport be back in time. “Let Love In” doesn’t have that same nostalgic glow for me but it makes up for it in sheer timelessness.

Hunter Felt is currently wrapping up over a decade-long tenure as one of the main sportswriters for the US version of The Guardian. To follow his current and future endeavors, check out

his Patreon page (https://www.patreon.com/hunterfelt).

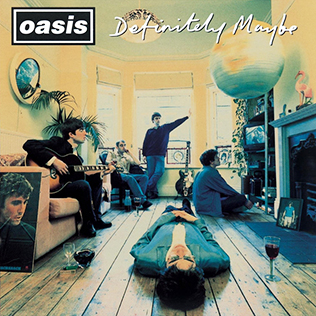

Next is Brian Love, with some introspection about a stellar Oasis album.

I was 20 years old when Oasis released Definitely Maybe. Maybe that was the perfect time for it to come along. 20 years old, in college, in love, the world was full of promise and possibility and passion. Definitely, maybe (probably) life was just beginning, everything was coming up aces. The joyous optimism of "Live Forever" spoke to that infinite promise and possibility. "Supersonic," still Oasis' best song, was about heedlessly embracing the adventure (and the risk), consequences be damned--after all, when you're 20 years old, you do feel supersonic, bulletproof, absolutely immune to the dangers and the darkness.

If I'd been more self-aware at 20, maybe I'd have heard the hints that Noel Gallagher was laying down, that definitely, maybe, everything doesn't always turn out like you dream. "Slide Away" tells the story of a love affair with as ambiguous an ending as that of Benjamin Braddock and Elaine Robinson--if you care to hear it (I didn't). "Cigarettes and Alcohol" hid some fairly existential questions about adulthood underneath seemingly party-friendly lyrics, if you bothered to pay a little attention (again, I didn't).

Life, eventually, catches up with you. No maybes about it, no one is truly supersonic. As I turn 50, I am acutely aware that I am closer to the end of life than the beginning, and that I definitely will not live forever (nor do I want to). The world isn't easy, and it isn't perfect. But I can throw on Definitely Maybe, and still kind of remember a time when it seemed like it might be.

The author, Brian Love, is an attorney in St. Louis, Missouri, who hopes that his daughters still believe they might live forever, at least for a few more years.

Next is Chad Jewett of Perennial (what a great band) writing about Mars Audiac Quintet (an album I need to listen to based on this read)

Here in New England it’s almost winter. By the time you read this, the solstice has probably come and gone. From here it’s the long expanse of early-sunset months, where it feels like you’re always within a few hours of nighttime; most of the time you are. Sometimes — when there’s enough snow on the ground to catch the glow of streetlights and Christmas bulbs — the evening hours somehow seem brighter than whatever an early January noon can muster up. If you’re like me you have soundtracks for these stretches of the calendar. Something that rhymes with the texture of the days, even as it savors of summer (which might as well be academic in February). It’s the perfect time for Stereolab.

Part of this has to do with the depth of the London experimental pop group’s catalog. 10 albums, all somewhere between “excellent” and “perfect”. A whole additional discography of B-sides and rarities collections; generous cornucopias of indie modernism. Along the way you can chart mini-eras that range from the scrappy basement pop of C86 to 60s-and-70s-indebted crate-digging eclecticism to beat-focused minimalism. Stereolab had a rough outline for their type of song — tuneful, carefully tailored, heavy on texture and usually adhering to one particular groove — but the details and shading of that template could land anywhere between warm psychedelic pop and avant-garde electronica. “Jenny Ondioline” (from their second record) is beatific; “Diagonals” (from their fifth record) is scientific.

Of all those early Stereolab LPs (let’s say everything between Peng! and Dots And Loops), Mars Audiac Quintet (turning 30 this year) feels like the “pop record”. The band’s signature addition-and-subtraction layering (picture a collection of color transparencies, stacked atop an overhead projector) is so often in service of hooks, searching out dotted-eighth notes and gaps between bass lines where another melody can fit, like spots in a floral arrangement. Geometric ribbons of electric bass and guitar loop away above the sparkle of electric organ, all a collage of shimmering texture. Maybe that’s why I reach for this LP so confidently as I drive past snow-blanket lawns dyed Technicolor for the holidays.

Few records will make the purchase of your most expensive set of headphones feel more necessary. “Three-Dee Melodie” is a model exhibition of sonic decoupage, right up until the moment Lætitia Sadier offers her biggest hook (you’ll know it when you hear it); then it’s just a perfect pop song. The other signature element here — the band’s wit, their ability to blend philosophical depth with such effusive melody — is already entirely at work by the time the band made Mars Audiac Quintet. Stereolab never went in for the feigned apathy or irony of the 90s. They had better taste than that. They read more interesting books. Spend a half hour listening to “Transona Five” a half-dozen times. The song swings and struts like some arthouse cocktail of The Stooges and XTC, as Sadier offers variations on a theme: “They are one and the same / Two inevitables, two inevitables / We can't avoid dying”. Check out how “Transporte Sans Bouger” (“Transported Without Moving”) churns under its sizzling organ, the title a nice, snug fit for the song’s modified motorik rumble. The way the horns blossom up on “Ping Pong” predicted Broken Social Scene. The way so many artists in the late 90s embraced a stylish blend of electronica and lounge music? “Des Etoiles Electroniques” got there nearly a half-decade earlier.

Stereolab are true originals; the best band of the 90s; perhaps the most adept group ever in terms of turning every element of their project — the songs, the videos, the album covers, the tour posters, the merch, the carefully curated reissues — into thoughtfully rendered dispatches of pop art. You know a Stereolab song when you hear it; you know a Stereolab shirt when you see it. In some ways you could think of Mars Audiac Quintet as their Rubber Soul: an early landmark that finds the band officially and definitively carving out their style while simultaneously deconstructing their record collections with dazzling wit and originality. But the reality is that Stereolab are entirely unique: as definitive a modern pop band as you’ll find. You can find a sound for any season on Mars Audiac Quintet. I sincerely hope you get started right now.

Chad Jewett plays guitar and sings in Perennial, an art-punk three piece from New England. Their new album ‘In The Midnight Hour’ is available everywhere chic modernist noise is sold.

Stay tuned for Part 3 tomorrow!

Add a comment: