#4: Where The Streets Change Their Names

This week: quests to explore Egypt from WC2, alternative histories of Covent Garden and Ricky Gervais origin stories.

Ed Jefferson is attempting to visit every Mews in Greater London. This week: quests to explore Egypt from WC2, alternative histories of Covent Garden and Ricky Gervais origin stories, but first…

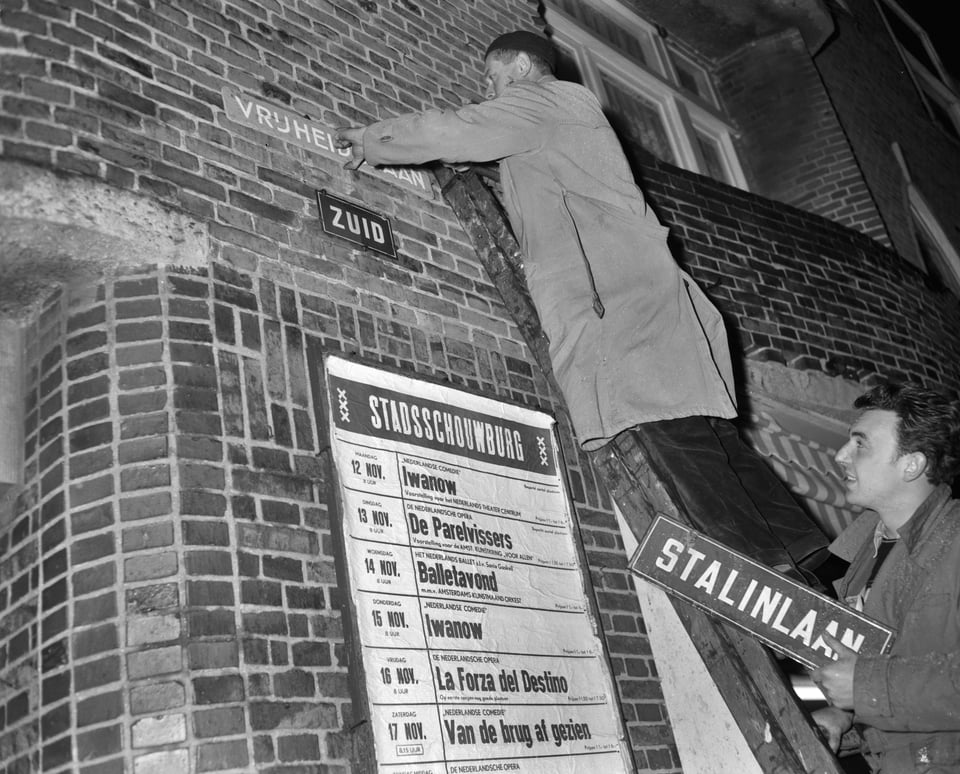

In 2017 Geoplace, the government body that maintains the official database of UK addresses, issued guidance that local councils should stop naming streets after people on the basis that once beloved national figures kept turning out to be horrendous monsters - the obvious example of this problem being ‘Savile's View’, a footpath in Scarborough.

Adopting this as a blanket rule has provoked some contention - earlier this year a council in Bedfordshire had to backtrack after preventing a village from naming roads after soldiers listed on a local World War I memorial. Everyone will regret this when some poor soldier who died aged 20, in 1918, gets cancelled!

In the other direction, what do you do about extant street names named after problematic people? While no-one seems to have been that bothered by Savile’s View disappearing, other instances have proved more controversial. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, cities across the world reflected on whether who or what the street namers of the past had chosen to celebrate - e.g. slave traders and white supremacists, was still appropriate in the 21st century.

In Hackney, Cassland Road Gardens (name derived from slave trader Sir John Cass) was renamed Kit Crowley Gardens (name derived from a locally-beloved figure who worked at a nursery school attended by many children of the Windrush generation). A more hotly debated change took place in Haringey, as Black Boy Lane (origins unclear but many of the plausible options not great) became La Rose Lane, after social activist John La Rose - this led to various kinds of very normal vandalism up to and including sticking a massive poster of the old name behind one of the new signs.

One group who took particular exception to this kind of stuff was the UK government, who passed a law to make it harder - a provision of the 2023 Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill notes details that local authorities must demonstrate evidence of support for any street name changes before they can be made, ideally by referendum (those are always good, eh?).

Even, for some reason, granting the best will in the world to people who oppose this stuff, the preciousness about changing street names is a bit odd. London in particular has a history of being spectacularly unprecious about it - from the 1850s to the 1940s1 the Metropolitan Board of Works, and then the London County Council, had an active policy of renaming streets, assigning new identities to thousands upon thousands of them.

The problem they had was that as all the stuff around London had coalesced and became part of the expanded city, it turned out people didn’t have that much imagination when it came to naming streets. That street that crosses the main road? Let’s call that Cross Street, right, it definitely won’t be an issue when it turns out there are about 60 of those. Or a few dozen King Streets, Queen Streets, New Streets, and so on and so on. This was confusing and unhelpful for many different purposes, but in particular made it quite difficult for the Post Office to work out where letters were actually supposed to be delivered to - and so over the following century much effort was expended in making sure everyone could have a reasonable chance of working out where a given street in the city actually was.

Everyone who lived on near the affected streets was perfectly happy with this and did not piss or moan about it all. Just kidding! From an 1869 letter to The Spectator:2

No human being, unless indeed his name is Smith, ever knows how dullwitted the majority of human beings are till the name of his street has been suddenly changed. An alteration of numbers is bad enough, but if the name of the street goes too, everybody's identity is temporarily lost, postmen sink back into second childhood, tradesmen send everything to the wrong house, and one's cousins gleefully protest that they could not find the way.

150 years later, we can probably reflect that this was not, after all, that big a deal. Sometimes things do not be like they used to, for all sorts of reasons that may not make much sense to you personally. That’s okay! Except if you try to change the name of any of the Mewses in my list before I finish visiting them. If you do that I will not be held responsible for my actions.

MEWSES VISITED THIS WEEK

#31 Book Mews, Camden, WC2

The origins of this alleyway’s name would have been easier to guess in Charing Cross Road’s heyday as the centre of London’s book trade - ‘The Bookshops of London’, compiled by Martha Redding Pease in the mid-1980s, lists over twenty different bookshops in which you could have found tomes on more or less every topic imaginable - and this when Pease notes that the trade is ‘in retreat’! This has now dwindled to just three because of Jeff Bezos, spiralling commercial rents, millennials will who only read TikToks, and so on.

The alleyway here was, for much of it’s existence, nameless - it backs onto 120 Charing Cross Road, once home of the first branch of the Books Etc chain, which in 1987 refurbished the building and added a back entrance for their offices here. When they asked BT to install a whizzy new 1980s-type phone system, some arcane bit of bureaucracy kicked in and demanded the alley be a given a name, and after much mindtaxing, well, the rest is history. As is Books Etc, mostly - swallowed up by American firm Borders in 2002, which collapsed in 2009 after having spent a decade responding to the rise of the book market-shattering Amazon by sticking its head down a toilet and going ‘gub gub gub’. The Books Etc brand survives as a family-run online store run from a trading estate in Aldershot, where they do not appear to have got to name any of the roads.

#32 Parker Mews, Camden, WC2

An access road leading to a car park, and some residences behind Parker Street, this is the last remaining stub of the original part of Shelton Street, which was built over when the old Winter Garden Theatre was redeveloped and expanded in the 1960s as the New London Theatre. The theatre is perhaps best known for having hosted the original version of Cats for approximately 1 million years (by presumable not co-incidence, Lloyd Webber has owned it since 1991), and it has subsequently been renamed the Gillian Lynne Theatre in honour of said production’s choreographer, the only woman who isn’t Royalty to have a West End venue named after her. Is that jellicle?

#33 Harpur Mews, Camden, WC1

I entered this Mews via a narrow doorway on Harpur Street, through an alley that must have once been the front hallway of a house, to find an overgrown, forgotten bit of the city clinging on by its fingernails - a row of apartments presumably adapted from the rear portions of the houses on Dombey Street to the north, and now boxed in by the enormous office building to the south. A residents’ noticeboard contains a single item, a handwritten note objecting to another nearby planning development, dated May 2001. Unsettling. If you strain your ears hard enough you can just about hear Geri Halliwell’s version of "It's Raining Men" drifting through the aether.

#34 John’s Mews, Camden, WC1

The northern half was called John’s Place until, as part of the grand street renaming plan detailed above, the London County Council told them to grow up, and merged the two halves into a single street.

At the southern end is Holborn library, where I used to go and work sometimes when I was first self-employed, and if you have to use the disabled loo because the other ones are closed I can tell you from experience that the cord hanging down next to the loo activates an emergency alarm, and not the flush.

#35 King’s Mews, Camden, WC1

Not the actual King’s Mews, the name presumably deriving from King’s Road to the south, which got renamed Theobalds Road because there were too many roads named King’s Road (see above). Apparently at one point it was suggested the LCC was taking too much pleasure in stripping royalty from placenames and had been infiltrated by dangerous socialists. Still, the bit of Theobalds Road to the east was formerly called Liquorpond Street, so whoever chose not to just apply that to the whole road was, in fact, a coward.

#36 North Mews, Camden, WC1

It is a bit annoying that this is called North Mews despite being directly south of another Mews, isn’t it? Okay, it is also directly north of another Mews, but you think someone would have taken the opportunity to sort this out at some point, wouldn’t you?

#37 Brownlow Mews, Camden, WC1

A plaque proudly announces that this Mews won the 2023 “Mews in Bloom” award off an estate agent specialising in Mewses, though to be honest the competition for this can’t have been that great given the ‘bloom’ is some vines over the pub and a bunch of potted plants that are… fine? They’ll give out awards for anything these days because of woke.

#38 Doughty Mews, Camden, WC1

Home to, among other things, the Egypt Exploration Society: “We started the archaeological survey of Egypt in 1890 and hoped to copy the surviving monuments in 10 years,” reported member Henry James to the Sunday Telegraph in 1993, “Only we haven’t finished.”

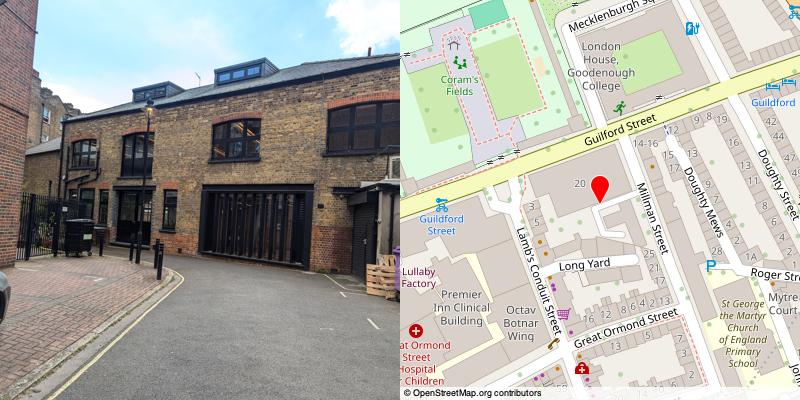

#39 Millman Mews, Camden, WC1

Was once home to Mr. Beard's Stereoscopic UK Daguerreotypes, where you could get a rubbish olden days photo done in the 1840s. Must have been fairly rubbish even for then because Mr Beard went bankrupt.

When I lived in this general vicinity in the 2000s3 you would occasionally see TV funnyman Ricky Gervais jogging round here, thinking up offensive things to say while wincing. Did he borrow the name of his Extras character Andy Millman off of the Mews or Street? Is it offensive to say that? Did I offend you? *makes a face*

#40 Heathcote Mews, Camden, WC1

Gated off alleyway that’s part of Goodenough College, which sounds like a joke from a middling comic novel, but is actually a halls of residence founded by banker Frederick Goodenough to house students coming to from London from all the far-flung bits of what was then the British Empire - these days it houses international postgraduate students regardless of whether Britain squatted their homeland for a bit.

At one point there was a somewhat different plan for the land here - it was to become the new Covent Garden Market. The surrounding estate was formerly the Foundling Hospital - a vast children’s home - which in the 1920s decided to relocate to leafier climbs in the suburbs. Covent Garden market had long been deemed to be ‘a problem’ - the site, which had hosted the market since the 1600s was not well-suited for modern purposes, but adapting in situ was going to be complicated and expensive.

The market had been purchased by the Beechams family (of pharmaceuticals, Lucozade, etc fame) in 1918, on the advice of financier James White, who appears to have also been a key figure in the idea that the market should pack up and move to the site of the Foundling Hospital. Also involved was industrialist Arthur Du Cros, who while MP for Hastings was so publicly opposed to women getting the vote that some of them burned down his house.

In the end there was a lot of opposition, not least from the market traders, and the proposal collapsed, which was probably for the best as both White and Du Cros had fairly dubious track records, to say the least.

Total failson Du Cros almost bankrupted Dunlop tyres, which his father had helped found, before going on to invest lots of money with Clarence Hatry, a man who himself committed fraud on such a vast scale that it was a contributory factor to the Wall Street Crash. White ended a career of screwing up lots of other people’s investments by screwing up his own and ultimately offed himself by drinking acid in 1927. The question of Covent Garden market was finally resolved in the 1960s when the government bought it and moved it to Nine Elms. They’re now redeveloping that because no-one can leave anything alone can they? Why does it have to be different and not like what I remember?

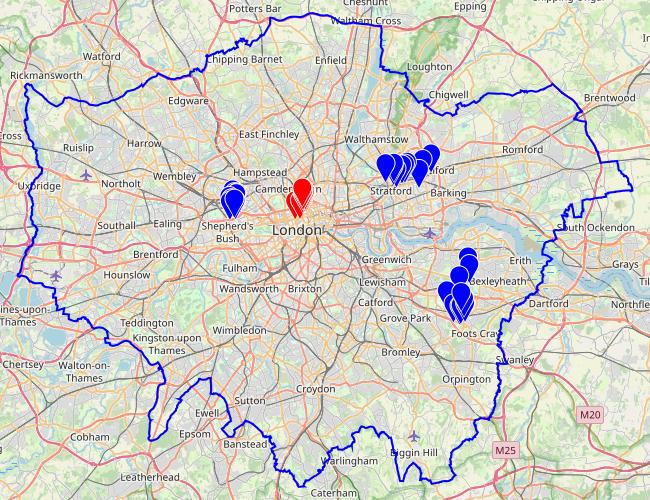

Total mewses visited: 40/2380

The Mews Letter is written, researched, produced and directed by Ed Jefferson so everything in it is his fault - apart from the facts about the real world, which he can claim barely any responsibility for. See more stuff at edjefferson.com.

But also see the 1811 letter to The Gentleman’s Magazine reproduced here: “The practice of giving new names to streets appears to me to increase very much of late, and is, in my opinion, generally speaking, very absurd”.

Found via Deidre Mask’s excellent The Address Book which goes into some detail about various things I’m touching upon here.

It was almost affordable to do so then, if you didn’t mind living in what amounted to a hole in the skirting board next to Jerry the mouse.

Add a comment: