Study: Interactive Fiction

Interactive Fiction is a rich well of material for Memex

This newsletter is about an indie game in development under the working title "Memex". I'm building in public as part of the process of bringing these ideas to life.

My initial approach to developing Memex was to write a novel. I've since spent a considerable amount of time studying story structure, character arcs, archetypes, and more. I've developed a few short stories based on the broader universe under development, trying to explore different facets of the world and history, while developing a more consistent writing practice. There's also a rudimentary outline for the first installment in a trilogy, and an even looser outline for the trilogy itself.

As I've worked on that concept and reflected on what I want to achieve with this project, it felt like a novel would be too constraining for the type of story I wanted to tell. Although I don't know how far I'm going to go with any of these approaches at this point (a more traditional puzzle platformer feels far more interesting than some of these options), I'd like to at least document my thinking and approach on considering various flavors of interactive fiction.

Parser interactive fiction

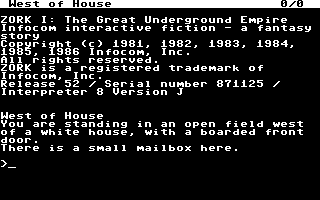

Some of the earliest computer games were parser-based interactive fiction. Stories like "The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy", "Zork", and the original way back in 1976 "Colossal Cave Adventure" would present the player with a brief description of the opening scene and command prompt. Players would then input commands like "examine mailbox", "open mailbox", and "get leaflet".

These games were extremely popular in the earliest days of personal computing, in part because typing commands into a prompt was the primary way of interacting with a computer. Home video game consoles hadn't quite emerged yet, and interactive computer graphics were still a few years away.

One of the key drawbacks of parser interactive fiction was the learning curve. Remembering all the verbs you could use and developing an understanding for how to provide the right input to the parser was a skill all on its own. Once mastered, these games were richly rewarding, however the investment required to pick them up relegated them over time to being more and more of a niche.

Today, hardly any parser interactive fiction games are published on mainstream platforms like Steam or Nintendo Switch (indeed, it's hard to imagine playing Zork on a TV without a keyboard). While there is still plenty of interest in this and other varieties of interactive fiction, it is certainly more niche.

Modern parser adventures can be constructed using languages like Inform 7 by Graham Nelson, which provides an impressive text-based system for adding rooms, objects, and interactions. It's definitely worth playing around with if you've ever enjoyed a parser game and wondered how they work behind the scenes.

I made a prototype Inform 7 game and, while I liked what it could do, the lack of visual presentation limited the audience to those who can type. My goals with this story are not entirely aligned with the constraints afforded by Inform 7 or parser fiction in general, so I moved on from there.

Point-and-click adventure games

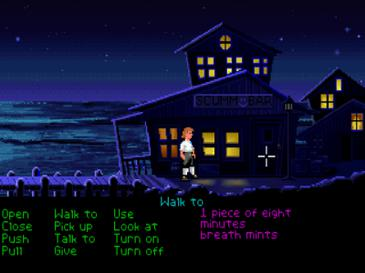

LucasArts and Sierra Online games dominated this genre in the 80s and early 90s. "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade" or "The Secret of Monkey Island" and its sequels were familiar to me growing up beyond the text-based parser adventures like Zork. You point and click, and your character walks around the screen. You can apply verbs from a menu or a wheel that appears when you click, making it far easier to know what you can interact with, and what verbs are at your disposal at any given time. In my mind, the visual aspect of these games (often with pixel perfect or even hand-painted artwork that pushed the limits of what was possible on contemporary hardware) pushed the parser-based text adventures out of mind. Why play a game at a parser when you can see and discover similar worlds with the visual and auditory appeal of a movie?

Visionaire Studio, Adventure Game Studio, and the Escoria framework for Godot are all modern tools for producing games such as this. Visual Novels are apparently pretty doable in the Ren'Py framework as well, which leans far more on the dialog and choices and far less on the "point-and-click" interactions, although in my mind they are adjacent in the world of interactive fiction.

I'm still mildly open to doing a point-and-click adventure game (they are among my favorites from childhood). I think they offer an interesting balance between puzzle solving, exploring, and storytelling. That said, I've not found a framework that I like enough to make it entirely compelling as an option for now.

Branching choice narratives

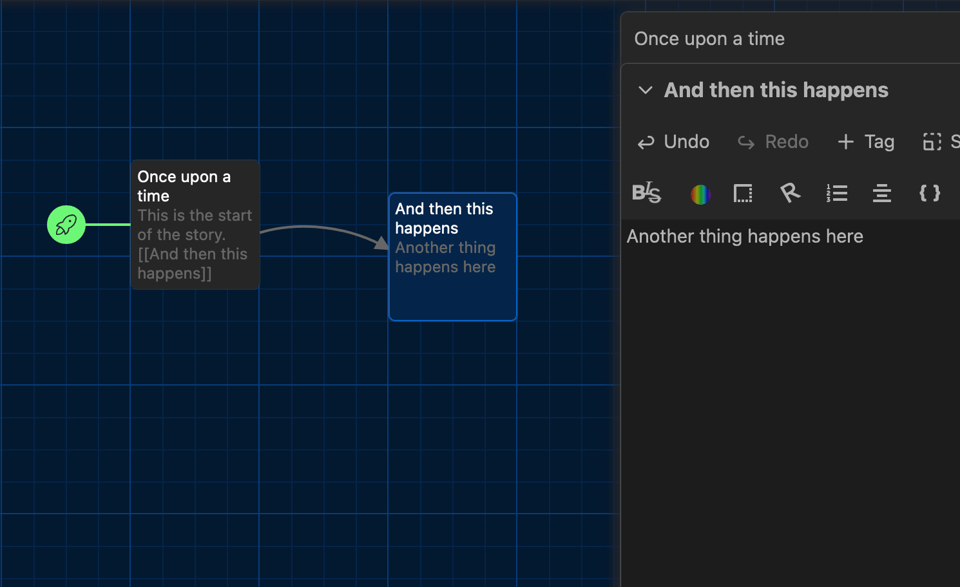

This is a broad term that could encompass parser or point-and-click games, too. I'm going to include in this category games where the primary presentation is text, perhaps some audio & visual elements, and you then choose from a list of options in order to advance the story.

Twine is an excellent tool in this regard, as it bundles into a single HTML file and is easily editable. I've developed a few prototypes using Twine as well, and found it to be a fun way to build simple playable stories. Branching and exploration of spaces without having to learn how to write another programming language are nice perks.

You can think of Twine as a way to write choose-your-way stories, letting you jump from scene to scene, and making it easy to present graphics along the way. The programming options can also run pretty deep, so it's not as expressive as Inform 7 or other parser options, but the constraints make it easier to actually ship something you know is going to work out alright.

The problem with branching choice narratives seem to me that writing compelling, complete stories along multiple arcs is really difficult to do well. Smaller stories that are easier to play through to get through all the content are a better fit, compared to having to start over and play multiple hours to get other differences. In other words, Twine works well for short stories, but not for longer novels. It's also relatively limited in interactivity - you can choose the next step in the story, but you're limited to choosing from a list of options to keep things going.

An honorable mention goes in here to Knights of San Francisco and the eGameBook framework behind it. It takes some of these ideas and extends them into a more fully fleshed out game, which is worth exploring on its own.

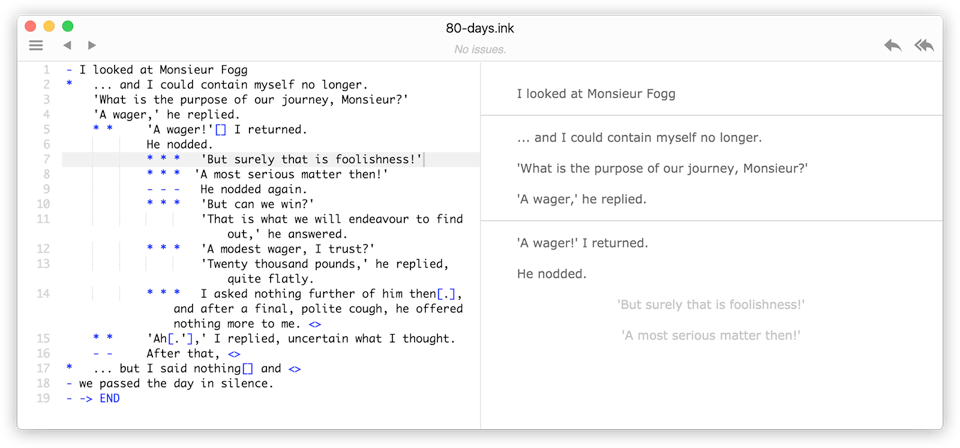

The Ink Engine

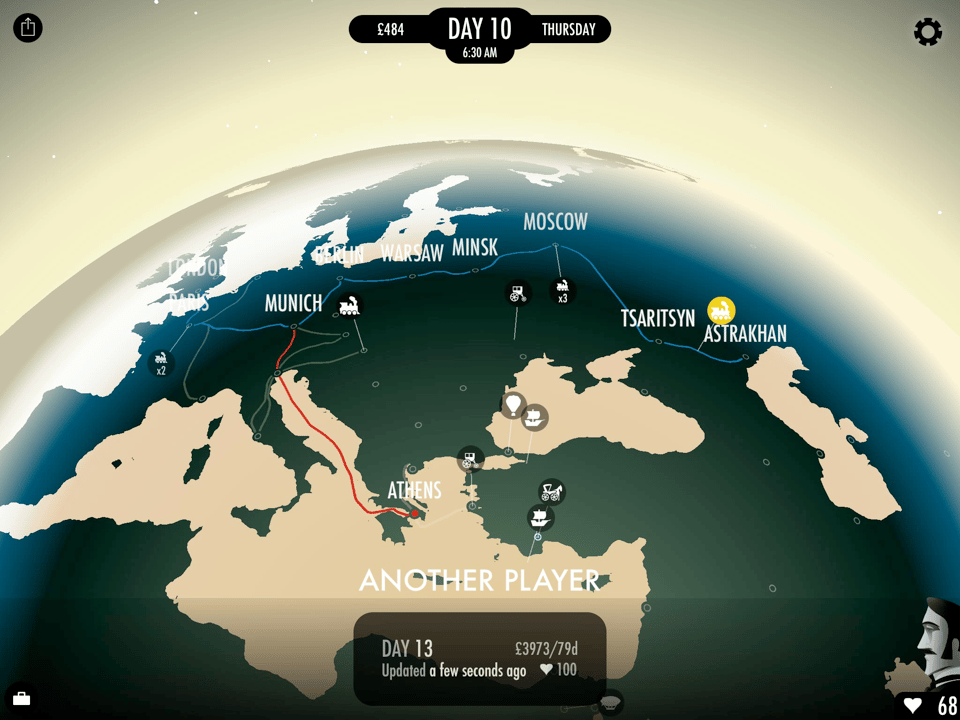

Ink is a bit more technical, and deserves its own section here. It's at the heart of a number of award winning mobile, desktop, and console games by Inkle Studios including the 2014 Time Game of the Year 80 Days, Apple Design Award Winner Overboard, and Heaven's Vault.

Ink is a scripting language for creating chunks of content that link together, similar to Twine. However, instead of being bundled up as an HTML file you click on, Ink's interpreter expects to be embedded in your own game or engine, like Unity or Godot.

This means that instead of being stuck with clicking the next link to play the game, your game engine can ask Ink for the next chunk of content and the options to choose from, and you can choose how to present that content and those options. In the 3D adventure Heaven's Vault, for example, the player moving around the world is provided as input to Ink instead of having to click a specific option like "Look at statue" in the story.

Inkle Studios is famous for extremely branching narrative - it's infeasible to fully map out every path you could take through 80 Days, for example, and all of the dialog options available to you throughout.

I've also developed a prototype in Ink of a few concepts, and I could still see using it in a more broadly built game. Currently, nailing the intended mechanics and concepts for the prompt, "What happens when you can hold a memory in your hand?" is the focus. If branching narrative storytelling is a key ingredient in the mechanics that support that prompt, then I can see myself leaning into Ink quite a bit.

Interactive...Books?

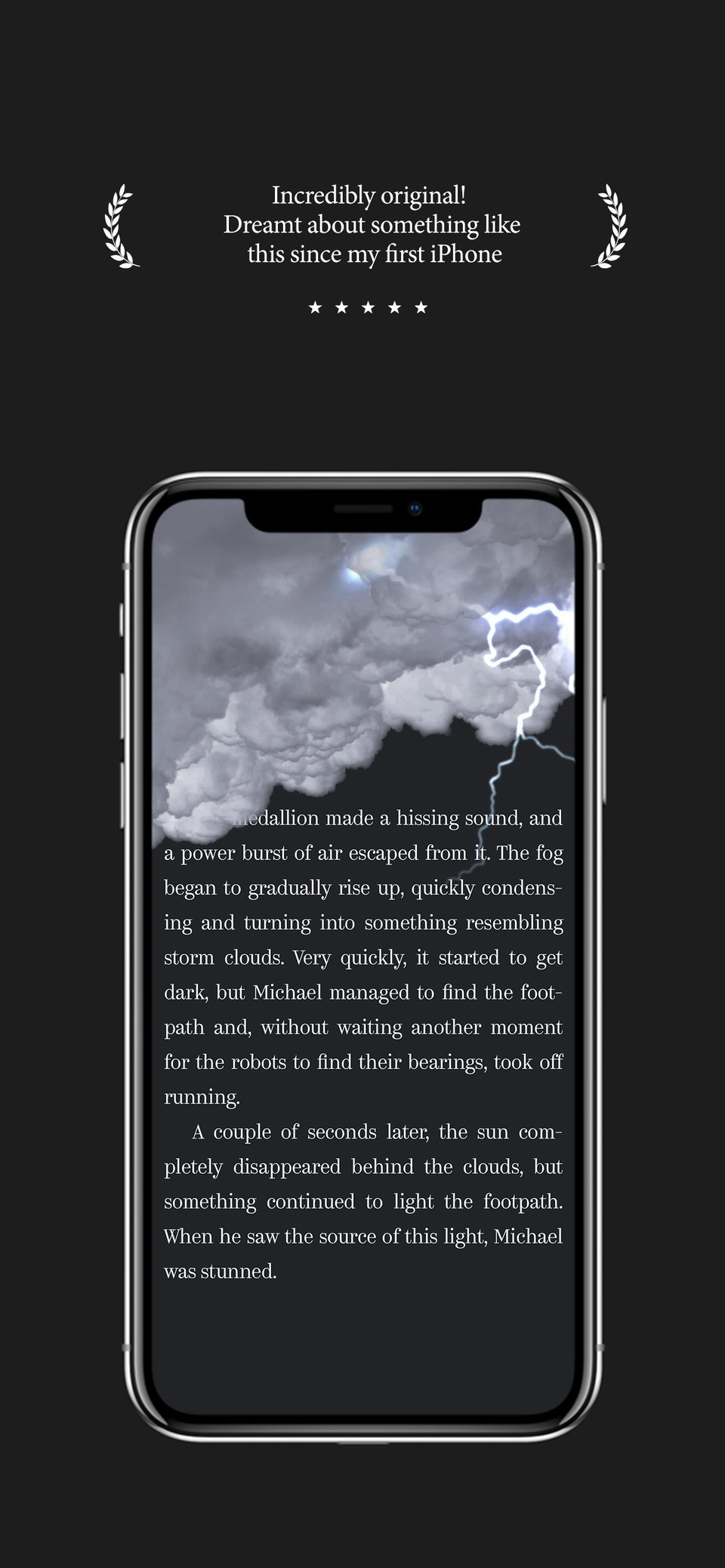

I'm not sure how to classify these next two examples, but I think they're worth a look. Maginary presents itself like you're reading an eBook, however in order to turn the pages you need to solve certain puzzles like realizing you need to turn up the brightness on your screen, or shaking your phone. These interactive elements are augmented by clever on-screen effects. If you're reading about being in a field with a light breeze, the text on the page bends slightly in the wind, for example. If the main character needs to go south east, a compass appears made of words, and the words follow the compass on your device.

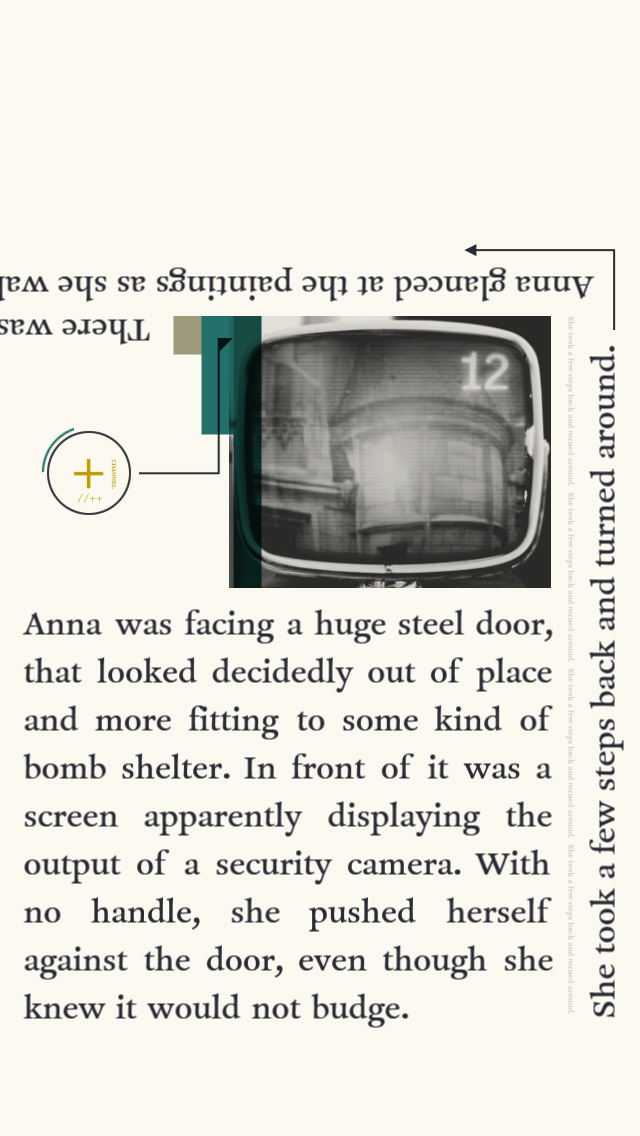

Device 6 by Simogo is a short story presented almost like a novel, however when the text says that the main character, Anna, turns a corner or goes down stairs, as you scroll the text you have to start scrolling to the side to head in that direction. Sometimes the text doubles back on itself. Clues are peppered through the text and small squares of graphics that exhibit a parallax effect. It's tough to describe in words, so play it yourself or watch a playthrough online to grasp the full effect.

These clever mechanics make for a great storytelling experience on both apps, and I've taken them under consideration as I design the mechanics for the story I want to tell. In particular, I've considered using a Device 6-style storytelling format where the text expands and changes as you jump into more of a puzzle platformer within the text. For example, in Memex you could start reading from the text, presented like a fairytale. Some parts of the text could then hint that you can jump into the story as a playable scene. Once completed, you are able to exit to the main narrative text, and move forward.

One point of consideration is that text is not particularly readable on TV screens without being very large. There's a reason we don't read books on our TVs and instead rely on devices that are at a much closer viewing distance. Am I likely to publish to a console? Probably not, but the idea is still too appealing to me to rule out entirely. This means I'll want to playtest prototypes on a TV to decide if it's feasible, and whether I care more about this mechanic or more about the option of publishing to consoles in the future.

What this means for Memex

A lot of this post is about outlining prototypes I've played with myself for developing the concept of Memex. Starting with the work on developing Memex as a potential novel, and then deciding that I really do want it to be an interactive "Art game", I have a few options on the table at this point:

Ink is an excellent engine for highly branching narrative, however Ink is a technical solution, and I'm still working out what problems I need to solve first.

I like the idea of the story being "written" as you play, and that choices you make within the "game world" reflect in the manuscript of the "overworld". The exact way this will play out is still to be determined, but this is a moderately firm concept at this point.

This means that the starting point for the game would be the manuscript of the story, starting with something as simple as "Once upon a time..." and having each subsequent block of story presented based on player interactions in the game world.

"Memory diving" into playable scenes could provide inputs into branching narrative if I want to be that ambitious. It could work just fine with a mostly linear story as well.

One of the nice parts of this approach is that individual playable scenes could be developed independently and loaded into smaller chunks of content, which is a common pattern when developing with Ink. 80 Days, for example, is built out of scenes that essentially run within one or a handful of cities or on a journey with a single vehicle. Actions in Paris don't really have a tight impact on events unfolding in Moscow, for example. There are a few exceptions, like choices made in Vienna coming back to influence the story in a few other places in the game.

Keeping each narrative chunk atomic and including playable content within that chunk makes for a modular game design that is both flexible and doable: I can complete smaller pieces of the game and let the narrative elements weave the overall game together as a whole.

If the game is text heavy, I will want to play test thoroughly on a TV to decide if I need to make a tradeoff between a text-heavy game and the option to publish to consoles.

I want the game to be extremely visual. A future blog post may go into greater detail about games I'm taking as influence, but at a high level I'm looking at TetherGeist, Gris, Child of Light and its influences from John Bauer and Kay Nielsen, and illuminated manuscripts like The Book of Kells (mentioned in the previous blog post).

Celtic knots are wonderfully mathematic in their construction, meaning they can be procedurally drawn based on inputs or choices made by the player. This could be used to gate parts of the manuscript with visual barriers.

Getting the art effects right on this is a big part of the challenge I'm facing as a solo dev. I can probably handle pixel art, getting things that are more sophisticated than that together is doable but also going to be somewhat challenging.

This is where point-and-click adventure games become more interesting, since they are from an era where it was challenging and still doable. Static backgrounds with a few animated elements could still be doable for a team of one like myself.

Even so, most of the bones of the game do not require fantastic visuals at this stage, and those can be developed over time.

Next steps

From here, it feels like I need to prototype the basic building blocks of something like this - same conclusion as last week. Here's the outline:

An overworld you can read like a novel. Maybe the entire story is presented and readable within a few minutes, however as you dive into certain parts of the story you get to see how the narrative changes away from what's given to what could be. Getting to that discovery and tailoring the output of the text is what makes the game interesting to play.

There are some interesting dynamics to consider around whether the entire text is visible at once, or if it unfolds piece by piece and the stuff that's already put down is now more or less permanent.

Prototypes feel like the next step to take here in any case. Here's to making that happen! I may still publish another blog post before sharing any prototypes, as I'm finding getting it written down in this format is helping to distill my thinking, but I've got to start shipping at some point!

Until next time, be good to each other.