Bigger on the inside

How to craft compelling game mechanics

This newsletter is about an indie game in development under the working title "Memex". I'm building in public as part of the process of bringing these ideas to life.

There are 26 letters in the English alphabet. There are 12 semitones to an octave. Groups of red, green, and blue pixels make up all digital images.

In each of these systems, a finite set of rules and constraints gives rise to a seemingly infinite degree of variety. Shakespeare's sonnets, Bach's fugues, and all computer art are made up of permutations of these simple systems.

Each of these systems could be said to be bigger on the inside than on the outside. The set of rules can be memorized pretty quickly. Mastery of those rules as an expressive medium takes a lifetime.

Climbing a hill

Sometimes we hear about a creation that "takes on a life of its own". It's like we reach a tipping point as creators where our efforts to give life to our vision go from feeling like pushing a boulder up a hill, to chasing the boulder down the other side. It's out of our control.

Reaching that tipping point is a critical goal of any speculative venture. It's a tail wind that makes everything easier and more direct. You are transitioning from an unknown, exploratory space full of noise and potential, into a space with a strong signal guiding you towards something good.

Exploratory work is squishy, it's not clear what's going to work and what won't, it's iterative. It benefits from rapid experimentation. Once you've figured out what that core experience is going to be, however, the roadmap unfolds ahead on how to finish the rest of the experience.

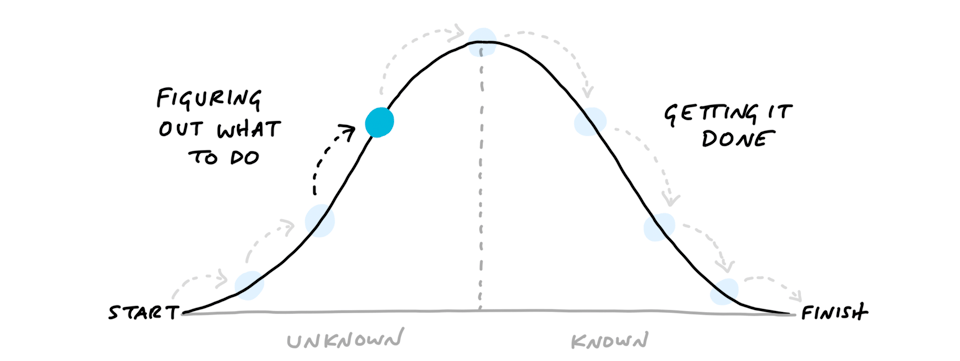

Basecamp's Shape Up method calls this out explicitly with their hill charts:

Moving from the messy, high-noise/low-signal space on the left side of the chart is a search problem, finding our way up the slope of figuring out what to do. Once you've defined the constraints you're going to work in, much of the work fills in itself. It becomes clear how to fill in the remainder to bring it to completion.

Good mechanics create more than they consume

In the Braid Anniversary Edition Podcast Episode 4, Jonathan Blow and Casey Muratori explore this same idea from a different angle: the sum of a few key mechanics is greater than the parts. Casey points out:

What you're saying is that you have to think about the design process almost like you were thinking about a power plant. If it's costing you more to get design things out as what you're actually implementing to put in, you're probably doing something wrong and you should try to look at a different thing or move to a different space because all you're going to end up doing is making a very procrustean thing with not a lot of richness.

We could say, therefore, that good mechanics create more than they consume.

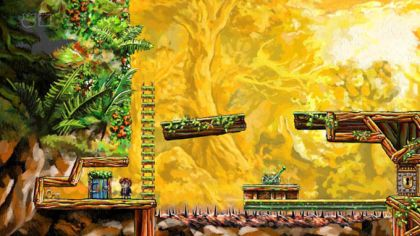

I think Braid does this very well - you ought to go play the game and listen to the anniversary edition podcast to get more of those insights. I will add that Braid’s core mechanics started out with “programmer art” and that the beautiful hand painted scenes came later. It starts with that pure concept at the heart of the game (For Braid, answering the question “What happens when you can travel in space and time?”)

Let's also consider Portal's mechanics, since it's well known and has simple mechanics that become highly generative.

Portal

Portal is built around a pretty straightforward set of constraints in the first half of the game:

You are trying to get to the exit in every room

The exit is blocked by doors, spatial barriers, and sometimes lethal robots

Doors can be opened by activating buttons with weighted cubes or by standing on them

You can navigate your environment with "portals" created from a portal gun.

Those first three points are extremely familiar to the puzzle-platformer genre, basically stemming back to the original Mario games and even Donkey Kong. The "portals" are the part that is unique.1

A portal is a temporary tunnel you can create on floors and walls, where you choose the entrance and the exit. In this way, you can put a portal on the other side of a lava pit, put the entrance to that portal right next to you, and walk through the portals to avoid an otherwise impassable obstacle.

This portal gun game mechanic becomes a highly generative design element, asking lots of questions that can then be answered in gameplay, like infinite falling loops, reaching terminal velocity and then moving a portal to shoot across a scene, and more. Once this concept crystalized at the heart of the game, the rest of the mechanics, level design, and more fall into place.

Another way of looking at it: the portal gun is a polarizing game mechanic. It attracts certain design elements and repels others. A portal gun doesn't make as much sense in a game of sudoku. Portals repel the potential game space occupied by sudoku. The portal gun does attract a lot of other elements, however, giving rise to a bestselling 3D puzzle platformer.

Therefore, we can say that a good game mechanic is polarizing. It acts like a constraining filter that eliminates huge chunks of the things we could put into a game, and emphasizing or boosting the features that remain.

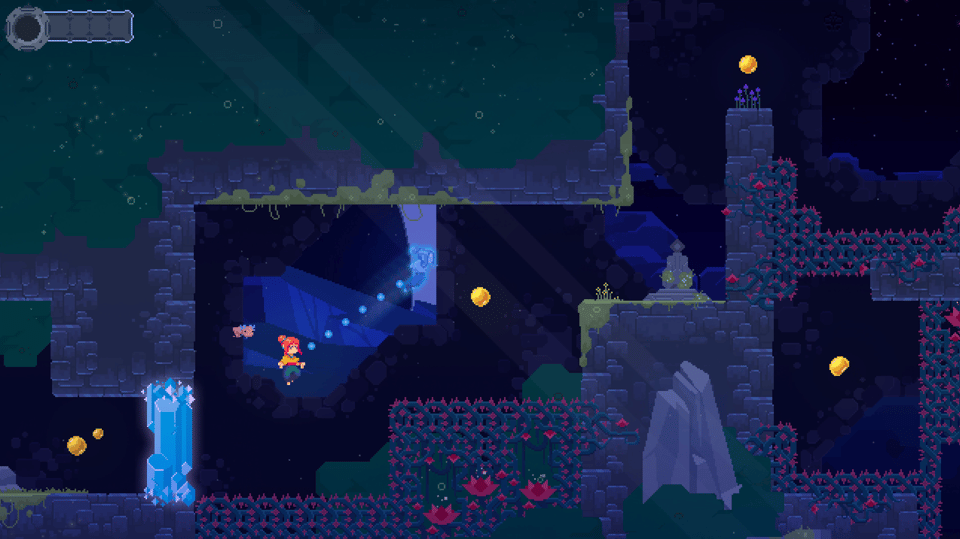

TetherGeist

Another example of a polarizing game mechanic is spirit splitting and joining in TetherGeist by O. and Co. Games, a small indie studio with award winning game jam entries going back many years. Each game jam entry is an exploration of a different core mechanic, like musical puzzles or using color to control what you can and cannot collide with (similar to Hue).

TetherGeist's mechanic of spirit splitting and merging was initially prototyped in response to the GMTK 2021 game jam prompt, "Joined Together."

This core mechanic is pretty well established in the Game Jam version of TetherGeist and seemingly the process from that point to a completed game has been about iterative refinement on that core idea. While certainly there's more to it than this, getting a good polarizing core in place brings clarity to design. When you know what isn't going to change, it sets the boundaries of what can change. That core has been tweaked and extended, but was pretty well established in the initial demo in 2021.

Simple rules, complex patterns

Another way of looking at this is that if you're trying to explore a novel design space, you need to develop a set of interrelated rules that give rise to complex, interesting patterns.

Douglas Hofstadter's book Gödel Escher Bach famously explores these sorts of patterns, describing how various systems can fold on themselves recursively, where just a handful of rules can generate a wide variety of diverse and interesting patterns. Stephen Wolfram as well has pointed out similar patterns in his work on computational irreducibility - the patterns that are more interesting are the ones that are not periodic, but complex and unpredictable beyond the next step or two in the simulation. Getting that just right is a key component in good game design.

Getting it right

Getting these sorts of mechanics right seems to be at the heart of any well designed game. The set of rules must be reasonably finite–we can't spend the entire game in tutorial mode learning new things, but instead taking a few basic inputs and expanding them out. Indeed, we can think of the inputs on a game controller as being finite and relatively static, yet almost all games interpret the same signals from those controllers in a myriad of different ways.

Key Questions

So, as a game designer, the key questions become:

What are the building blocks for our mechanics?

What operations can we use to move between states?

Do those things give rise to predictable or unpredictable patterns?

What elements are repelled by my core mechanic? What elements are attracted by it?

How does the core mechanic set the constraints that create a boundary around any game and just your game?

For Memex

For the game I am developing, I'm still in the process of exploring potential spaces and game concepts. The prompt I'm exploring is pretty well refined at this point:

What happens when you can hold a memory in your hand?

While I have developed some broader storytelling points around this (stuff that could be worked into a novel, for example), I haven't quite figured out the core game mechanic involved.

Although not a fixed constraint yet, I am biased towards making this game a puzzle platformer. One fixed constraint is zero combat. TetherGeist and Gris are very much in spirit what I've been looking to achieve with Memex: there is peril, but violence is not the key struggle.

I think the next question is: what can a player change in the world by holding a memory in the palm of their hand? What magic can be wielded with the idea of a memory that can shape or affect the environment around the player?

For Gris, jumping, running, climbing, timing, and turning into a cube of stone are all key mechanics. Apart from the cube of stone, none of these capabilities are particularly different from most other platformers. So, perhaps that is a good enough starting point. Gris' key selling point is the atmosphere of art and music that permeates the player's experience. Gris feels like a profound work of art in its craftsmanship. That seems to be what polarizes "good" and "bad" for Gris. That's the measuring stick.

TetherGeist's mechanic makes for more interesting and challenging puzzles than Gris, however. Whereas Gris is mostly about timed platform jumping, TetherGeist's mechanic introduces "impossible" puzzles that can only be solved by mastering the unique properties of the game.

Portal has the same feature: puzzles are impossible without the "magic" of the portal gun.

A few ideas that I'm considering:

There are two realms: The real world, and the world of memory.

The real world changes when you manipulate things in the world of memory. By jumping into the world of memory, you can solve light bounce puzzles that illuminate or reframe the perspective on certain memories.

This changes the real world so that, depending on how you solve the puzzle, the narrative of the puzzle changes in the real world.

The primary game world/"overworld" is presented like an illuminated manuscript.

A page from the illuminated manuscript “The Book of Kells” Maybe you collect pages of this manuscript with traditional platformer jumping mechanics, and once you collect a page of the story, you can bring different perspectives together to unlock different ways of looking at the overworld.

Jumping into a page takes you to the more abstract puzzles. The perspective and framing of different memories in the story are what give you the ability to move forward.

That seems like it could be a good enough start for a platformer.

Next steps from here will be to try and create a playable prototype that features this core mechanic.

In a future post, I may explore some past ideas I've had around interactive fiction to mine them for further ideas on the shape of the game.

Until next time, be good to each other.

In some ways, you can think of Sid Meier's "rule of thirds" here:

One third should be the same as what came beforeOne third should improve what cam beforeOne third should be new or novel

I think that the improvement on the genre of existing puzzle platformers was incorporating more story & atmosphere than others had up to that point. ↩