An occasional series of essays by Matt Carmichael: now in paperback Kindle, and e-reader versions! See more at meetingmyheroes.com.

Books are a gift. But author readings are an absolute treasure. Not only do the authors give you the book, but they often come to your town to read it with you, or sign it or talk about it, or all of the above. They’re as concerts are to records, but usually way more intimate. They’re a great way to meet your heroes and learn from them directly. Assuming your heroes are a bunch of authors, I guess. (I will now have Moxy Früvous stuck in my head.) I’ve told some stories in longer form, like Orson Scott Card and Douglas Adams, but I’ll do these as a series of shorter vignettes.

One of the best classes I ever took was a high school English class focused on Short Stories. The teacher put together an amazing reading list of classics of the genre and introduced two sections worth of avid readers to Carver and Cheever and Shirley Jackson and one author who became a particular favorite for me, T. Coraghessan Boyle.

I loved his short fiction and his novels and he, like Mitch Albom to an extent, showed that good writing can take you in a lot of different directions. Not just that he could be serious or funny, but that he could write short fiction and long form. He could also write non-fiction and tell really compelling stories that might not have sounded like the kind of set-up that would lead to a good story. If there’s one theme that has often woven through his work it’s the fragility and importance of our climate and that of course resonated with my hippier high-school self and my futurism-leaning present.

I met him at, I think, a Border’s book store (checks notes, in September 2000) with my friend Liz who was also a fan. There were maybe 25 folks there?

Neal Stephenson and Bruce Schneier

A little earlier (May ’99) I met Neal Stephenson. His was touring after the release of his book Cryptonomicon, which was a sprawling history of cryptography and World War II spanning 800+ pages. I devoured it in three days as I recall. He was going to do a signing at Stars our Destination, where I met Orson Scott Card. That was an incredible book store, dedicated to science fiction and fantasy and helped create community around these interests, too.

My roommate at the time, Jack, had a friend Sprite who worked there. She was a sweetheart, with green hair. Somehow she managed to sneak me in ahead of a lengthy line and get me a staff t-shirt commemorating the event that I still have.

He was touring, as I recall, with another author Bruce Schneier, whose real-life cryptography scheme, Solitaire, was used in Stephenson’s book.

Later I would meet Schneier again at SXSW after a talk he gave there. His work at the intersection of tech and privacy couldn’t be more important and it was fascinating to hear his talk and then chat with him a bit at the book signing later.

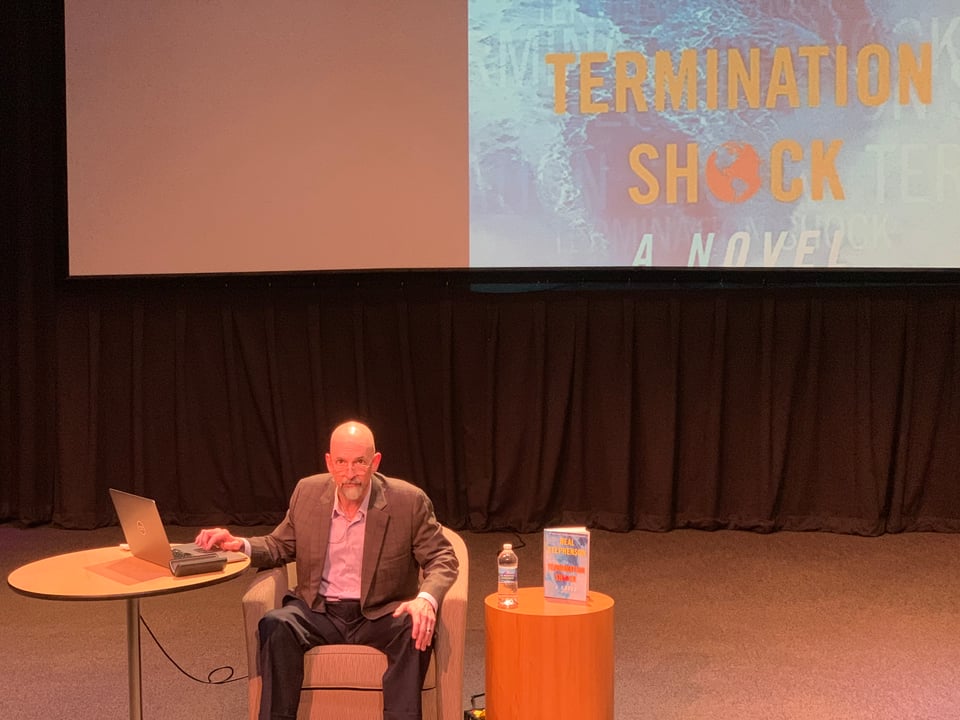

I saw Stephenson again right after things started to open up after the pandemic. He was touring then off of Termination Shock, another climate-focused book. The premise of that story is kind of a scary one: What happens when today’s “crazy” ideas don’t seem as crazy anymore because tomorrow’s reality has gotten so out of hand. It centers on an Elon Musk- sort of character who takes climate action into his own hands because he’s just gotten bigger and more powerful than most governments. The results of his actions have global consequences creating winners and losers in the race to stave of climate catastrophe.

His talk was not what I expected. He gave a university-style lecture using PowerPoint to talk through some of the science behind the book! I asked a question during the Q&A about the Metaverse, a term he had coined a long time ago, but which was finally reaching a point with of moving from science fiction to a technology exploding in possibility in the present.

Later, at SXSW, he did a fireside chat about the book and one of the points that came up in the discussion was that as dystopian as his book was, it was important to remember that we really have made a lot of progress on climate change. Projections made in the ‘80s and ‘90s spurred action that has actually slowed things. But also, that progress is fragile, too, as we’re seeing today.

William Gibson

I haven’t met William Gibson… yet. But I did get to interview him for Cover Story. His book, Neuromancer, coined the term cyberspace and set an aesthetic for modem-based hackerdom cum every day life with the Internet in the 1990s and well beyond. He creates worlds that suck you in and make you dream of new things. And he did all of that while not being tech-savvy himself. Stephenson plunges into the worlds he writes about and creates, like the gaming research for Reamde or working to understand cryptography and how it works. Gibson did less of that but nonetheless imagined futures that have come to pass. You don’t have to live and breathe a world to write about it. But as Stephenson shows, it can lead in different directions and different kinds of nuance when you do

Gibson also, decades later, was pretty accessible via Twitter and we had a fun back and forth of a couple tweets about what to call alternative proteins of all things.

In pulling this together I dug out the interview I did with him of course, and I love the last question I asked him, especially in light of my current occupation: “Do you consider yourself a futurist?”

Here was his response, “I think of what I do artistically as exploration of new ways to apprehend the present ... I think I'm pushing back against what the late 20th century is doing to me. Better than trying to extrapolate or map where we're going. I never think of the things I write as being literally predictive. I think science fiction's predictive capacity is chronically overrated.”

I’m really curious (and will try reaching out to see) if he still thinks this way. So many things he and many other writers including the ones mentioned here have written in have seemed prophetic and if nothing else thought-provoking in a futurey way. I mean, what is the Wikipedia if not the embodiment of the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Minecraft spun out from Ender’s Game…. The list goes on.

And that’s part of why I read Science Fiction. Not only is the best writing in the genre just plain good storytelling, but it puts me in a mindset to think about all the things that eventually led me to where I am now.

Here’s the interview I did with William Gibson for CoverStory.

William Gibson just put me on hold. The Canadian author, who defined "cyberspace" in his novel "Neuromancer," is excited that I am still on the line when he comes back. I am the first person he has done that to successfully. "I'm not very good with technical things," he says.

Gibson's short story "Johnny Mnemonic" has been turned into a film starring Keanu Reeves. His latest novel, "Idoiu," is due out next year. He talked to CoverSTORY about the Internet, politics and too much information.

What was it like watching something that had only existed in your mind gradually transformed into physical being?

It's very very strange, and interesting.I think what was most intense for me was physically walking into the main set. It completely flipped me out for about two hours the first time I was on the set. Seeing it up on the screen in some ways a little more academic because you can then look at how it plays. But actually being there on a very meticulously realized set was extraordinary very spooky and wonderful.

How much input did you have in the actual filming?

A vast and by Hollywood standards, completely abnormal amount. It's the directors film but I bear a terrible degree of responsibility as well. Because Robert and I are both outsiders, absolute beginners we both invent our own collaborative relationship, which in terms of my involvement went far beyond what the Hollywood culture expects or allows the author to do. I was in the art department helping to build props at one point. That was wonderful.

After your experiences with Johnny Mnemonic, which do you think is more surreal: Hollywood or Singapore?

I would have to say Singapore because it is not leavened by the erie glamour that still sometimes manifests itself in Hollywood. There is some strange tricky glamouring lure in Hollywood that's still here. It's kind of amazing you just kind of glimpse it in the corner of your eye occasionally. Singapore doesn't have that. What Singapore suffers from a kind of terminal banality in my opinion.

Singapore's problem is that's its just really boring. It really is kind of like Disney Land with some kind of mean agenda. Mean and not very interesting agenda.

Do you consider yourself a futurist?

I think of what I do artistically as exploration of new ways to apprehend the present. The present is so shatteringly weird the day to day moment by moment at the end of the 20th century. It's actually so much stranger than we can grasp that we need that we need the tools that have traditionally been the tools of science fiction to get a grip on it, and in some ways to push back. I think I'm pushing back against what the late 20th century is doing to me. Better than trying to extrapolate or map where we're going. I never think of the things I write as being literally predictive. I think science fictions predictive capacity I chronically overrated. We just never get it right historically, if you check it out.

Science fiction was predicting television almost since the beginning of the century. The principle of it was understood, yet there are only one or two examples of anyone having predicted anything remotely like the culture of broadcast television that has completely altered our world in my lifetime.

You weren't a big computer user when you wrote ""Neuromancer"." Are you now?

I'm not a power user by any means, but I wouldn't want to go back to writing on a typewriter. To me, a word processors a power tool. It' like having an electric drill, an electric saw. It's the same job, it just makes it go faster.

What kind of computer do you have?

I use a Macintosh SE/30 which is kind of like driving a 1948 international Harvester truck, it's obsolete in a sense, but it's a very good machine.

Are you on the net?

I don't have an email address, I don't even have a modem. My kids are, but that's another matter. They spend hours strapped in there and sometimes I go and look over their shoulders.

I'm a big fan of the Internet in theory. I love the idea of it. But at this point in my life, the last thing I need is more information. More messages. The very thought of it makes me want to scream.

Is the ability to find and own information starting to play too big a role?

That's sort of like saying sunlight is starting to play too big a role. It's just there, it's what we do. Information is what we do that distinguishes us from other species. For a long time we've coming up with ways of disseminating it, mechanizing the process of the dissemination of the information. Sometime in the second world war when the Allies built the first electronic computer to crack the german enigma codes at that point we became post-mechanical. I think that was the point when we actually entered the information age.

Do you think print has a future.

Well, I hope. It's depressing to a writer to think that it might not. We do have the example, in fact a rather scary example of Brazil, an enormous country with a predominately illiterate popluation who get all of their information from the world's largest television network. So that can be done, I've never been there, but from a distance it looks like a rather scary society. It looks sort of the societies in some of my books where there doesn't seem to be a middle class.

Do you think that at some point "Neuromancer" is going to be a true vision

I could imagine that the Internet will evolve into something akin to the cyberspace of "Neuromancer". But "Neuromancer" is sort of already fouled with the kind of quaint anachronisms that science fiction novels accumulate as they travel through real time. The Soviet Union is still in the background. On the basis of what the characters do sexually, there is no AIDS. ""Neuromancer"" looks to me as very much like an '80s novel. The parts of "Neuromancer" that I really like are sort of like fables of Reganonmics. I see it as a kind of cautionary socio-political tale in some ways.

Why does AIDS play such a big role in virtual light?

It was the biggest story happening. When I wrote "Neuromancer", I'd never heard of it, nobody had ever heard of it. I think I got through "Count Zero" while it was kind of an emerging phenomenon. But by the time I wrote "Mona Lisa Overdrive," I had a character who was a teenage prostitute and it was necessary for me to kind of hedge a little bit. At some point she offers to show somebody her "blood works certificate," to get approved, to show her customer that she's clean.

When I wrote "Virtual Light" I was very concerned about it. A very good friend of my wife's and mine had turned out that he was positive. In fact, the guy I dedicated the book died shortly before its publication from aids-related complications. To me it's a very serious part of the book. The whole story shapely and what he does and how he dies. I saw that as the rock in the snowball. "Virtual Light" is in some ways a overtly comic novel. But at its core it's this hard hard thing, which to my mind is very much at the core of our reality today.

Why do you thank Laurie Anderson at the end of it?

I read an early version of virtual light in New York. The first time I read part of a new book, or a work in progress to a live audience is kind of a very critical point for me. She came an introduced me at this reunion. It made me feel much better about myself and about the book. I tend to get very discouraged in the course of writing books. Because once I get to a certain point I can see that it will never be as good as I want it to be. I'm never satisfied with it. So part of this is sort of helped by this because I'm in the middle, and in that case, Laurie got me over the hump. And Brian Eno got me to finish which is why I nod to him in the back. He told me that some art is best done quickly and go on to the next thing.

Now the three of you are all involved with GBN, correct?

My involvement with GBN is pretty passive. The fact that I don't do email probably shuts me out of the most interesting aspects of that group. I've gone to a couple of meetings. That's about it for me. My distrust of my own abilities as a futurist kind of throws me down. Because GBN is actually a futurist group. They do futurism quite well and interestingly but it's a different kind of imagination than what I do, as far as I can tell.

Why are you involved then?

I was invited actually. Honestly, what happened was I was asked to join and somehow managed to ignore the invitation because I was busy with something else and they asked me again and I said 'I have to decline this, I'm a little too busy,' the next thing I knew, I was "a member." It's very interesting and I enjoy being a member and getting the mailing and books and things that are sent to the members because it's a kind of prime source of good rip for my novels. I see a lot of material that I wouldn't see otherwise.

Have you been following the U.S. Government trying to regulate the Internet?

It's going to be tough because the Internet doesn't come from anywhere and it's trans-national. There aren't any borders anymore. My hunch is that they can't regulate it without crippling it, causing it to cease to happen.

On the other hand, I'm in favor of law in cyberspace. I think we should have law in cyberspace but should also have civil rights. We should have constitutional rights with regards to this territory.

A cyberspace constitution?

The problem with the technologies that create these sort of quasi territories the innovation jumps ahead of legislation. And in this case, I wanted to say is that the thing that fascinates me most about the Internet is that it really is global. It doesn't live anywhere. It doesn't emanate from any country. I know you know in the absence of some sort of world government I don't see how you can control the sort of end-user access because it's happening all over the world simultaneously. Every place in the world has an Internet site. One country's idea of pornography is anothers' Saturday morning cartoon.

Do you think its possible that politicians might be afraid of the power of the Internet?

I don't think politicians, by and large, have remotely begun to grasp what's going there. I think they knew, they might be frightened.

What do you think about hackers?

I'm kind of interested in what they do, socially, as an observer. But it sort of doesn't turn me on. It really depends on what they're doing on an individual case by case basis.

You just read issue #60 of Meeting my Heroes. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.