Meeting Orson Scott Card

On the complicated people who make complicated art

Meeting my Heroes is an occasional essay series from Matt Carmichael.

When I was just out of college and living near Belmont and Sheffield, I happened to live near the city’s (and really one of the nation’s) best sci-fi book stores, The Stars our Destination. Besides a fantastic selection and wonderful staff (including Sprite, a friend of my roommate, Jack’s) they would from time to time host books signings from some of the best authors of our time. And so I got to meet Orson Scott Card, who wrote one of my favorite books, “Speaker for the Dead,” the sequel to the also-awesome “Ender’s Game.” (And yes, that Ender is related to the Ender in Minecraft.)

Reading “Ender’s Game,” there were a couple of concepts I have taken with me over the years. One is that “the enemy’s gate is down,” which basically means you need to orient whatever you’re doing so that the goal is in front of you and your gravity will carry you forward, toward it. It can be as simple as turning a map as you travel. Or more intricate on a long-term project. Another was about winning wars, not battles. Mostly, that the world is complicated, as are people’s motivations and you need to try to stay human and empathetic as you go.

“Speaker for the Dead,” is about the complicated legacies of people and the value in telling the truth, even if it’s a hard truth. That idea has gotten a messed up over the years as people talk about being “real” when really they mean honest or even cruel without that empathy.

I shared these books with my dad, who also liked them a lot. Now I’m sharing (his copies) with my kids.

At the book signing, I picked up a copy of “Ender’s Game” for my cousin Ted and got “Ender’s Shadow,” one of the sequels, for myself. But while I was in line, the kid in front of me challenged Card on his beliefs about LGBTQ people. I think he called Card a homophobe.

Card pushed back, hard. It was clear he’d heard this all before and didn’t have much patience for it. He said some comments he’d made ages ago had been taken out of context and he tried to explain how he really felt.

Lesson one is it’s ok to challenge your heroes (maybe politely but firmly). Lesson two is to hear out your critics and respond to them if you think it’s worth it. Sometimes it’s not. Sometimes you’re not going to change someone’s mind and it can be exhausting to keep trying.

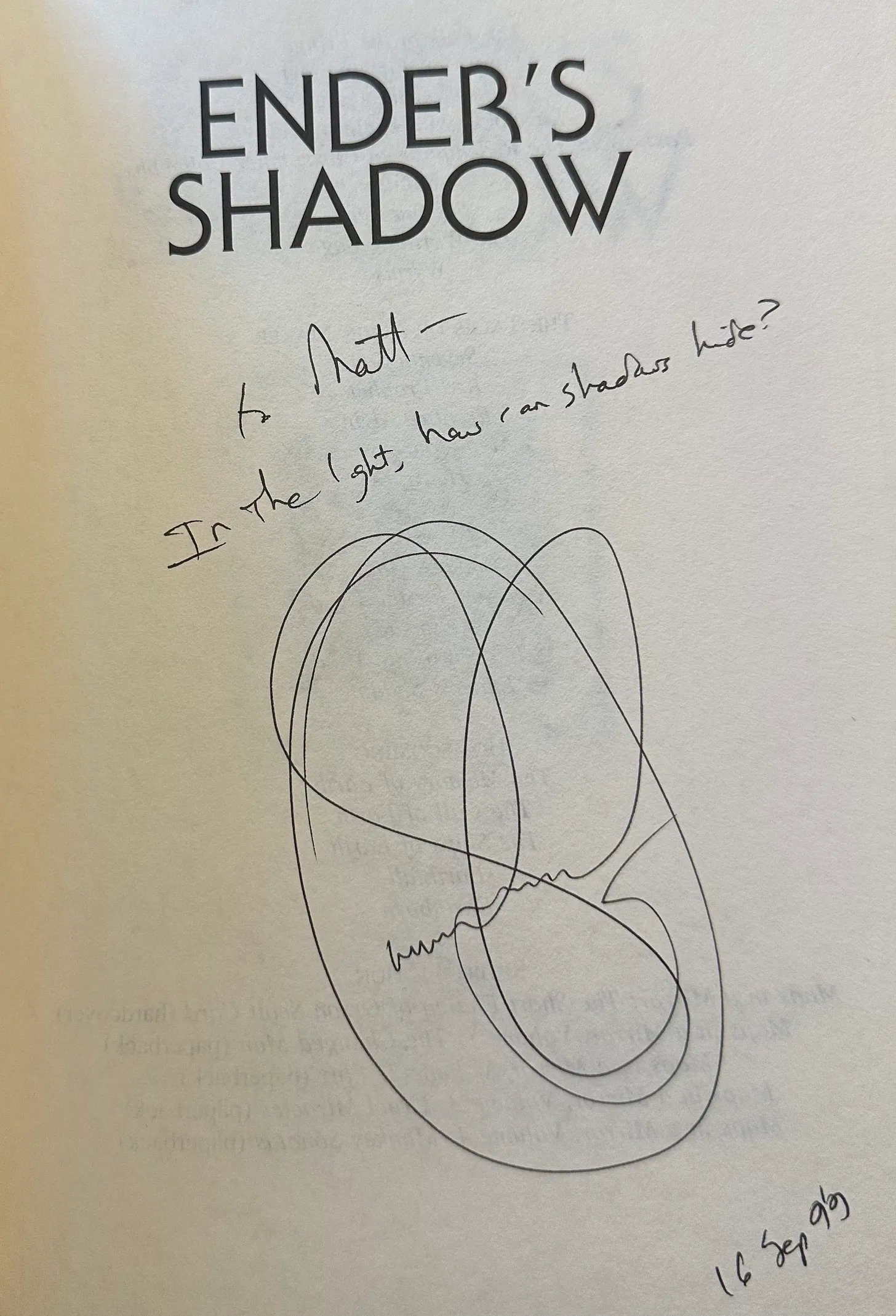

Card signed my copy of “Ender’s Shadow” with his amazingly artful signature. He wrote, “Matt, in the light, how can shadows hide.”

Unfortunately, Card’s shadows came out as more and more light was shown on them.

This was before “cancel culture” became a thing. The bigger lesson is that people can make good art, even if they’re not great humans. Card really seems to be not the best human. He’s made that more and more clear in the years since I saw him at a book signing, which was the first I’d heard of it. This Wired story, headlined “Orson Scott Card: Mentor, Friend, Bigot,” does a solid job of laying out how complex life can be.

There are a lot of philosophies about what to do with artists who aren’t great humans. Some take a zero-tolerance policy. Some consider how important they are to the history of their craft. In some cases, like Cosby, or Michael Jackson, you can’t really tell the story of comedy or pop music without them. I sometimes think about it in terms of, “does knowing about the artist change how you see the art.” Gary Glitter, I’m looking at you.

So, as you read Card’s works — or anyone’s for that matter — it’s good to keep in mind the ideologies of the person behind it, when you know what the are. Sometimes they’re obvious. Sometimes they’re subtle. Sometimes you don’t even know from reading it. JK Rowling, I’m looking at you, too.

But it’s all about becoming critical readers and thinkers, which are important skills than ever these days.

And despite all of his shortcomings, “Ender’s Game” and “Speaker for the Dead” are still amazing books.