An occasional series of essays by Matt Carmichael: now in paperback Kindle, and e-reader versions! See more at meetingmyheroes.com.

On the things we acquire and the connections we make.

As you’ve been reading, I like meeting the people behind the music, or writing or other kinds of makers. Between fandom and my job I’ve been able to make a lot of opportunities to do so. So far I’ve written about a lot of rock stars and other celebrities. But I have other kinds of heroes. Including some that will expose me for being an odd amalgam of nerdinesses. So this post is a bit of a confession about one of those spheres.

For a hot minute, the U.S. imposed tariffs on Mexico and Canada (as of this writing). Whatever your politics, you likely agree that a policy like that should help U.S. businesses. But that’s not the only outcome. Take Dearborn Denim, a Chicago-based manufacturer of jeans and other apparel. It faces daily challenges in its quest as a small U.S.-based manufacturer: how to sell and market its products, how to deal with lulls or sudden rushes of orders, how to balance the desire to make new products with the need to stock classics and favorites, etc. They source most of their materials in the U.S. but it’s not easy. There aren’t many cotton mills left in the U.S. making denim. They’re able to source all their cotton denim domestically, but they import their stretch denim from… Mexico. It gives them a really small and tight supply chain. Until tariffs.

The tariffs were quickly rescinded for now, but in the meantime the company announced it would try to eat the cost increases as long as it could, cutting its tight margins so it could keep its promise to its customers of quality jeans, providing quality jobs at an affordable price.

I have a lot of respect for trying to keep the cost from being passed on. But also, they shouldn’t have to be in that position.

I met its CEO, Rob McMillan, during a public tour of their factory, as short drive from my house. I took my family and we got to see where the jeans and belts and shirts are made. It’s all on one factory floor from cutting to washing and packing. Every station provides a good job for someone in my community. I have a lot of respect for that too.

Caring about where my jeans are made (and I wear jeans most days, now) is an offshoot of caring about where the things I carry with me are made, as well as the bags that I carry that stuff in. I prioritize companies that make things domestically for economic and a little national pride. But it has the side benefit of potentially meeting the people who literally make the things. These are some quick stories of meeting these creators and makers.

There’s a name for all of this stuff: everyday carry. You can read a really exhaustive version of this story, but it’s probably a little much. It was written to share with the EDC community. Because of course there is one. And if there’s a “leader” of this community, most people would say it’s Taylor Welden. You’ll meet him shortly.

What follows are some stories of meeting some of the people who made some of my things. It's probably worth noting some of the things I carry: * A space pen * A small microblade from WESN. (I also have an amazingly-left-handed Swiss Army knife, but it's a little big to carry with me). * A wallet (tho less frequently now because I have a great phone case with a card holder built in), which I'm glad to have had replaced after my old wallet and I parted company. That's a "meeting" story of a different sort. * And if I have my Tom Bihn backpack, I carry a bunch of other stuff. Including a blade-less, TSA-approved multi-tool, because you never know when you'll need a screwdriver. Speaking of my backpack...

Kat and the Tom Bihn factory

I coveted the Tom Bihn Synapse 25 backpack for quite some time. And by that I mean that I spent a lot of time thinking about and researching what would be my perfect pack. Turns out two friends and neighbors had the same pack. So although I couldn’t go to a store to try one out I could talk to them and see theirs. When I finally ordered mine, one of the online reviews mentioned that they would decorate the shipping boxes if requested. I did of course. Kat, a worker there, drew adorable little robots and enclosed me a hand-written note. Years later on a trip to Seattle, I finally got to see where my bag was made. The factory store is right in the factory so you can see the people sewing and cutting and crafting as you check out the goods. And who should greet me at the door, but Kat. Personal touches…. It’s not just a thing it’s all the things.

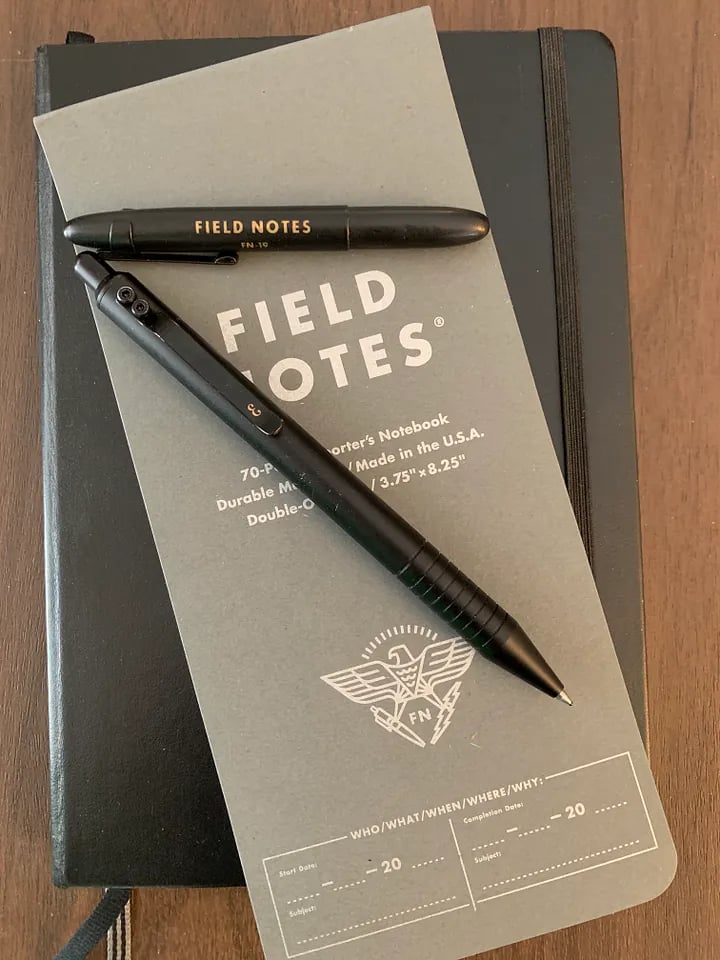

Field Notes

I love the idea of Field Notes. I just, um, don’t love the form factor of their usual notebooks. It doesn’t really work for me. But then they worked with a well-known journalist to make a proper reporters notebook and I now stop in a couple of times a year at Field Notes’ HQ to restock. It’s handy that they’re another Chicago-based manufacturer. When you are there in person you can shop old and rare releases, and you always walk out with a free pencil, notebook and sticker. I’ve met a few of their staff, one of whom did me, my kids and their classmates a pretty massive solid. Good people, making good stuff. On one visit, I noticed that their cobranded Fisher Space Pen (another American-made product) was essentially left-handed in that if you are holding the pen in your left hand the logo is right side up. You, as a righty, have never noticed that this is rare because your pens are always right side up. But I noticed immediately and then had to pick one up. I was chatting with Bryan whom I met on a store visit and he, the pen’s designer, had never noticed or been told that.

Patrick Ayoub, Detroit Watch Co.

Since my first Timex and later a series of Casio databanks I’ve always liked watches. And in adulthood I’ve wanted, but resisted, a true grownup watch. I did get a Shinola at their factory store. I went with my dad and my son on what I think was my last adventure with my dad. I will always cherish that watch, partially because three generations of Carmichael men were there to buy it. But Shinola, despite its Detroit roots, is almost a big company.

I’ve kept my eye out for something smaller and a little more unique. For me, that turned out to be the 313 area code watch from Detroit Watch Co. It’s a throwback design to a rotary phone dial. The leather bracelet has copper colored stitching to evoke phone wires. As a futurist, I especially enjoyed the irony of having a timepiece that in itself was several kinds of anachronism. Watches themselves are a bit of a throwback, and one that hearkens back to a technology as formerly ubiquitous but now obsolete as a rotary phone was just too perfect. That, and it looks so darn cool. It comes in a variety of area codes, and I thought having a 312 (Chicago’s prime area code) would allow me to tie it to both places I’ve called home.

Each watch is hand assembled by its designer, Patrick Ayoub. I emailed him a perhaps odd question. We wound up speaking by phone about my order. Among other things, he let me choose the serial number. I picked the number that marks the year I left 313 and became a 312 resident. My timepiece therefore bridges the two phases of me.

I asked if I could pick it up in person somehow as I would be in the Detroit area for my high school reunion. He not only agreed but it turned out I would be picking it up at his house. I don’t know how many times I had driven by it in my life. But it’s a lot.

We chatted about watches and Detroit. He told me that the success of his little watch company led Shinola to make an automatic movement for the first time. He told me how hard it was to get packaging in the US and how he had reached out to Defy among others about creating a watch roll for him. And once again I got to shake the hand of someone who made something important to me.

Chris Tag, Defy Manufacturing

It started with the Defy Square. A friend had one, and the Cobra buckles of course caught my eye. He told me about Defy, a local Chicago company.I was intrigued. Down a rabbit hole I went.

When I started reading about Defy and its story I was sold. A guy, Chris Tag, had had enough of the advertising industry and set out to start his own small business. It was a struggle, but eventually took off. They made everything by hand in Chicago. The early bags, like mine, used reclaimed materials like military tarps, seat belts and bike tire tubes. And those buckles. Austrailalpin Cobras. Something like $30 a piece, but they’ll never fail. That’s something you can, and many have, bet your life on it. Later they started making use of another local legend, Horween Leather, from a family-owned tannery nearby.

I love a good brand narrative or story. And I love the idea of small companies with real people making stuff with well-sourced, carefully chosen materials and pure passion. I spent too much time checking out their stuff. Watching for sales. Weighing options. My wife said I wasn’t cool enough for a couple of the bags, so I settled on the First Class. A messenger. My book was coming out. It’d been a hard and stressful time and I felt like I’d earned a reward. I wanted something unique. Something that was a tool. Something that would last. My wife didn’t entirely get my obsession, but supported the idea anyway and got it for me for my birthday.

My Defy First Class, showing off its mods.

I loved the look of the First Class, and confirmed that its front pocket could squeeze in my iPad mini. But it was missing something I liked in my current messenger. It lacked a back pocket to stash a magazine or some papers for easy access on the train or plane. Some of Defy’s other bags had something like that so I reached out on Facebook and asked if they could put a pocket on a First Class. That’s the beauty of small business craftsman. They agreed and I was sold. I picked it up in person and met Chris himself.

Even more amazing was a couple of years later, after many miles had been logged on that bag, I reached out again and asked for another mod. The bag had D-rings on the front, which added to the visual badassery of the bag but functionally meant that anything that you hung from them wasn’t covered by the flap. I asked if they could put one on the inside that I could hang my keys and have them protected. Again, they agreed and I took the bag into the shop. Chris was there and was proud to see one of his earlier designs return with some well-earned patina. I watched as he sewed it in, and met one of the other seamstresses and thus shook the hands that created this thing. Figured I should also pick up a Defy keychain I’d been coveting — with some of that pure Horween goodness. All the better to clip on my new ring.

Rob McMillan, Dearborn Denim

As I mentioned earlier, Dearborn Denim makes high quality, reasonably priced jeans and makes them a few miles from my house. Rob, its CEO and founder, used to be in finance but wanted to change gears. I started buying their jeans in 2018 or so. They have struggled a bit here and there. Opened and closed retail locations due to the pandemic. Had a hard time moving their factory to expand. Now, maybe tariffs, too.

They’re quite human about everything, including their marketing and the way they run the business. For instance, when they moved their factory they only moved it a mile so as not to inconvenience their staff of cutters and sewists with an uprooted commute.

By 2023 they were all up and running in their new space so they restarted their occasional factory tours. The tours are given by Rob, himself. brought my family and hopefully the kids got a feel for what hand-crafted looks like and how small a supply chain can be. Meeting Rob was fun and I did what I often do, asked in-person for an interview later. Here’s that story from What the Future’s Manufacturing issue.

-==-

How we can keep small manufacturing “Made in the USA”

Small business manufacturing has seen a resurgence in the U.S. in the last decade or two. A lot of that is fueled by direct-to-consumer and social media trends. Much capitalizes on the “Made in the USA” or “designed locally” labels as selling points. But can the momentum continue? Rob McMillan runs a small, blue jean d-to-c manufacturer in Chicago. He says it’s a constant struggle, but he hopes that people will continue to place a premium on good products, made locally, that last.

Matt Carmichael: How important is the role of “Made in the USA” and how do you see that changing in our polarized world?

Rob McMillan:“Made in the USA” is always important. It isn't just nuts and bolts. It's another source of jobs for U.S. workers; we need more options than desk jobs or the service industry. I know there are some fancy economists who say you can get the same product overseas for cheaper and you're supporting wages in, let's just say, Bangladesh, and there's truth to that. But I think it's okay to say as an American, I prefer to support jobs in the USA, I align with this person more just by living in the same area as them.

Carmichael: Does the sustainability of a shorter supply chain also play into the appeal?

McMillan: I'm always concerned when people are making greenwashing statements of “this is more sustainable than that,” but there is something to having goods move fewer miles, right? Freight is a significant source of CO2 emissions. Yet, I don't know if I'm fully convinced that that’s an argument I would make as to why you should buy local. I haven't done any studies on whether our jeans have a lower carbon footprint than imported jeans.

Carmichael: Other apparel companies totally make that claim.

McMillan: There are questions of economies of scale for manufacturing. Is a big manufacturer going to make a pair of jeans in a more efficient way than a small manufacturer? Yes. We also try and do stuff as efficiently as possible, But there’s a lot more to it.

Carmichael: Like what?

McMillan: Like, how efficient is your fabric cutting? Do you have 80% or 90% cutting efficiency and is that 10% waste? Is that being recycled? Is that going to a landfill? Maybe the most important one is how long does your product last, right? If you have to buy a pair of blue jeans once a year, or a pair that will last three years, you're consuming less. You're saving money and there’s going to be less waste. I'm much more convinced by that argument. There’s a ton of waste in the apparel industry primarily driven by fast fashion.

Carmichael: How do you balance efforts toward quality and sustainability with profitability?

McMillan: If we don't operate profitably, we go out of business. We don't have venture capital backers or anything like that. Our approach has been to make sure our customers come first. We are competing with the Levi's and the Wranglers, but also Costco jeans, and premium brands.

Carmichael: To what extent do you think “Made in the USA” and sustainability, etc., matter to your customers vs. they just want a nice pair of jeans?

McMillan: A huge portion of the U.S. is just constrained by price. Our jeans are too expensive at $75 for a whole bunch of people. That's one of the reasons why we tried the SVR jean at $39. But it was too low a price point for us at the time to make it work. I want to be able get a product to market at a lower price, but for now we have to stay in the premium tier.

Carmichael: What holds you back?

McMillan: It’s not the jeans, it’s the shipping. We subsidize too much. We're not Amazon. We also offer free exchanges. So that's another $9 out, another $9 back.

Carmichael: That’s a downside of the d-to-c model. But to what extent does that model and social media enable companies like yours to exist?

McMillan: Many other d-to-c brands don't do their own manufacturing. The idea that d-to-c was going to be more affordable than traditional retail is flawed because shipping costs are very expensive. Also, online customer acquisition has become very expensive, because in large part, it’s replaced traditional media. I don’t know if someone starting a business in 2024 will reliably find a lot of success.

You just read issue #52 of Meeting my Heroes. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.