Hi there, it’s me, Matt.

“Brand” has become such a common word: That’s not my brand. It’s on brand. Build your brand. This is branded content.

But what, exactly, is a brand?

Surely there are many books on the subject. But sometimes it’s fun — and educational! — to try and construct a definition from first principles (the pervasiveness of branding today makes this task quite a challenge). If you find yourself gasping at the same straws, I hope today’s essay is helpful.

First, a song. On “Snitches Brew”, Kamaal Williams puts together a hyperactive improvisational trio featuring guitar virtuoso Mansur Brown. It’s ecstatic, energetic, a little bit weird, but always in the pocket.

Now, on to the essay.

A few weeks ago, I jumped into a new job as the head of a design team at a startup called SimpleHealth. One of my first tasks is to kick off a big brand update. Full creative control, clear product/market fit, a long timeline — this is going to be a breeze. Right?

Only, I asked myself a question that — honestly — I don’t think I’ve asked in my 15-year career.

What is a brand?

This is a question that a director of design should be able to answer. I can’t answer it — at least, as I write this sentence, I don’t know the answer. And maybe by the last sentence of this essay, I won’t know the answer, either.

But I think I can boil this question down a bit, to see what a brand really comprises, to understand it more fundamentally.

A wrong start

A brand is a graphic that says “I own this thing.”

That’s not exactly right. But at one point in time, that’s all a brand was. The earliest examples of graphic representations of ownership date back to the ancient Egyptians: Egyptian herders would mark their cattle to deter theft. Marks of provenance extended to other vocations; in Ancient Greece, India, and China, ceramic makers would use everything from their own thumb print to simple symbols to sign their work.

Over time, since the best ceramics came from only a few of the most skilled potters, the potters’ signature became a key signifier of quality. When buying, selling, or trading, these marks were crucial to estimating the value of a pot. Fakes were rampant. 1

So, a brand is a graphic that says “This thing is of high quality.”

But that’s not quite right, either. At least, not today, because between 600 and 2020 AD we invented advertising. This innovation has changed the definition of brand entirely.

Advertising came of age in the late 19th century out of necessity. As manufacturers made more and more products, and stores increased their shelf space, companies tried new ways of identifying their goods. When imbued with attractive personality traits like thriftiness, cleanliness, youthfulness, and luxury, products stood out and sold better.

In the 20th century, Modern psychology and the advertising industry, blending concepts from propaganda, anthropology, and economics, have shaped the brands we are most familiar with. A brand no longer is just an identifier, a sign of ownership, or a marker of quality.

A better start

A brand is a way to quickly communicate the qualities of a company, product or service.

(A note on “quickly:” there needs to be an adjective in our definition of a brand. A brand isn’t just communication in general, or we’d see billboards filled with 12-point type explaining products in lucid detail. There’s something about a brand that requires brevity, efficiency, and … quickness. It’s probably not the right word. But this feels workable - it’ll do for now.)

Ok, so what qualities does a brand communicate?

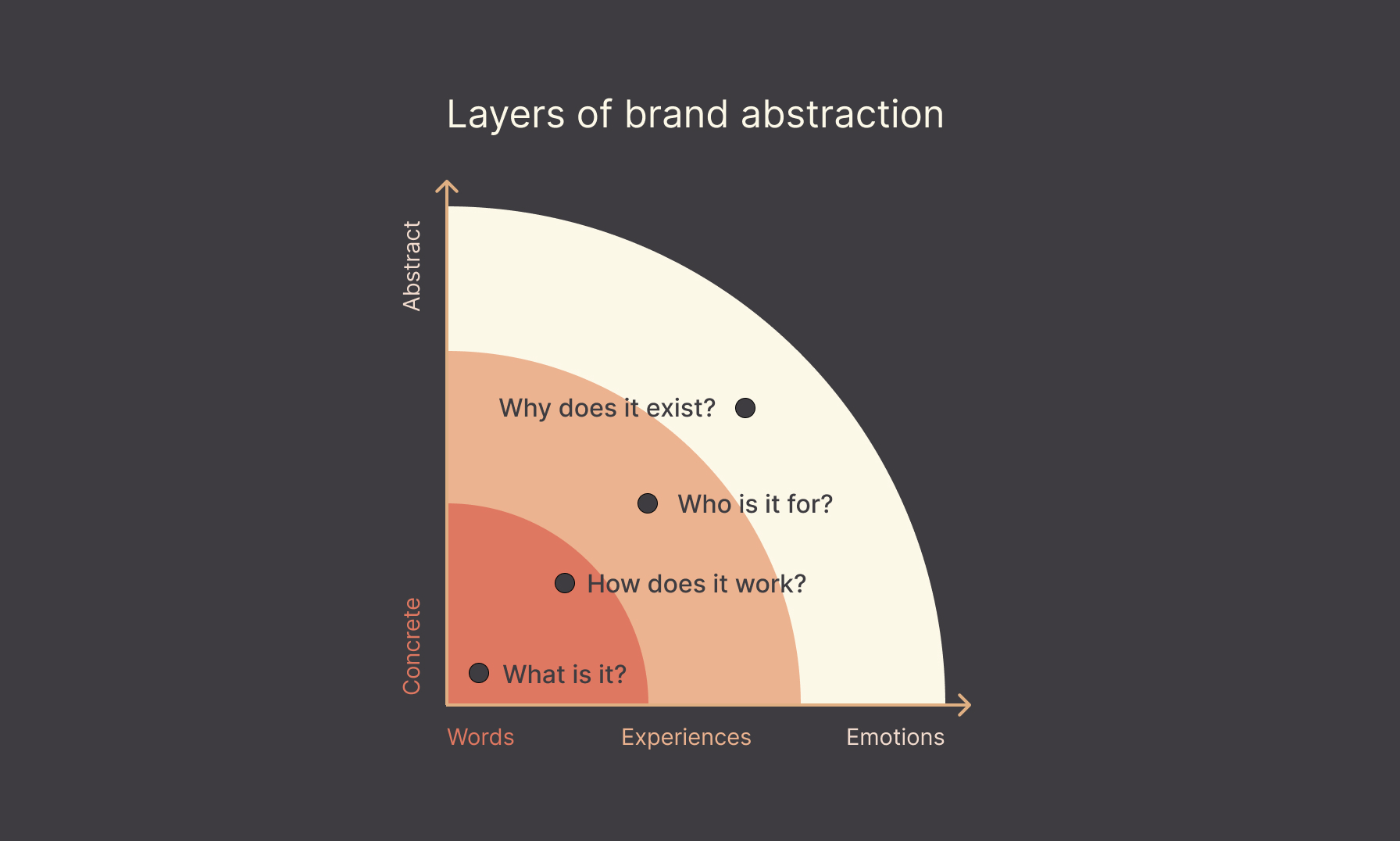

1. What it is

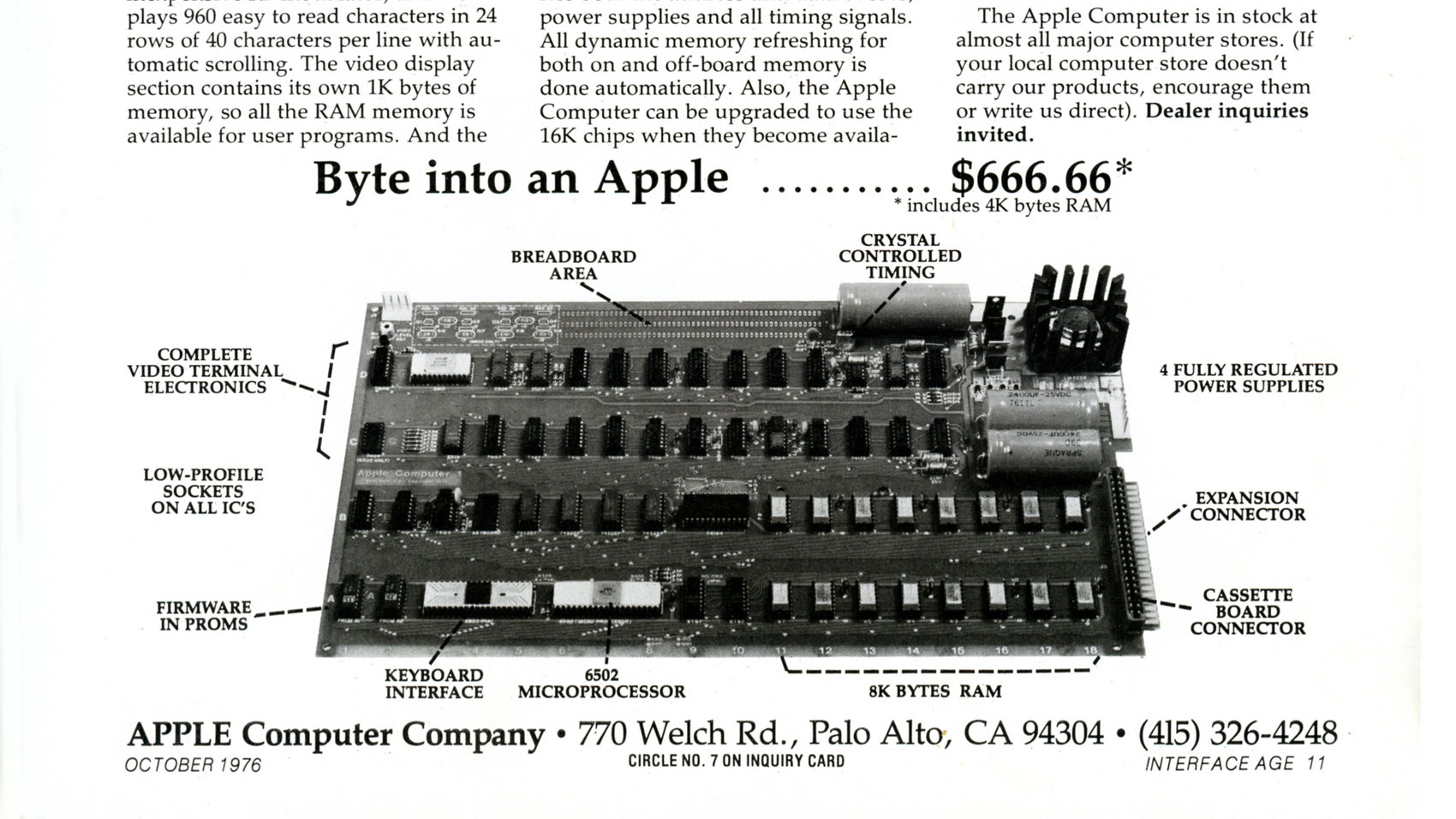

The most basic thing a brand should communicate is what, exactly, the company/product/service is. When Apple started its life as a two-man team, it was called “Apple Computer Company,” making it very clear that they sold computers, not fruit. When the company introduced its most revolutionary product to date — the iPhone — it shortened its name to “Apple Inc.”

2. How it works

When it launched in 1957, Dove sold a soap they called the “beauty soap bar.” Their advertisements carried a single message, spelled out explicitly at the very top: “Dove creams your skin while you bathe.” Then, at the bottom, “Dove is one-quarter cleansing cream.” That was Dove’s brand: it’s a gentler version of soap.

3. Who it’s for

Lululemon was founded in 1998, when Yoga was still a nascent phenomenon in the America. Gym clothes were not yoga-friendly; they were loose-fitting and poorly made, causing problems for yoga practitioners who needed to stretch and bend and happy baby pose on their mats. Chip Wilson saw this need, and created a brand that spoke to women who practiced Yoga.

4. Why it exists

](https://matthewstrom.com/images/brand-5.jpg)

Nike is one of the most recognizable brands in the world. But its success depends on the popularity on a bizarre hobby: running. “Run?” I hear myself asking, “for fun?” Nike spends billions of dollars every year convincing people to run — and, by the way, you’ll need some shoes to do that. Running is for gritty, strong, passionate, driven individuals. Nike helps you run.

I’ve put these qualities in this order because each one climbs up a rung on the ladder of abstraction. What you sell is much more concrete than why you’re selling it. And how your product works is easier to communicate than who it’s for.

Not all brands climb this ladder to the top. For a brand like WD-40, all four qualities are the same:

- What is it? A spray that makes things not squeak.

- How does it work? Spray it on, things stop squeaking.

- Who is it for? People with squeaks.

- Why does it exist? To stop things from squeaking.

And that works for WD-40. But most companies (and services and products) aren’t WD-40. They need to communicate more.

How can a brand get these messages across?

Brand layers

How a brand communicates varies widely between companies (and products and services). There’s a similar ladder of abstraction to be climbed here, and it can be seen in the way brands have evolved over the past 100 years.

1. Words

Early brands used words exclusively to communicate. Lucky Strike Cigarettes spelled it out in their early ad campaigns: “It’s toasted.” “20,679 physicians say Luckies are less irritating.” It’s “your throat protection — against irritation — against cough.” Words can communicate what, how, and who. The most powerful words — “Think different.” “Just do it.” “Because You’re Worth It.” — can communicate why.

2. Experiences

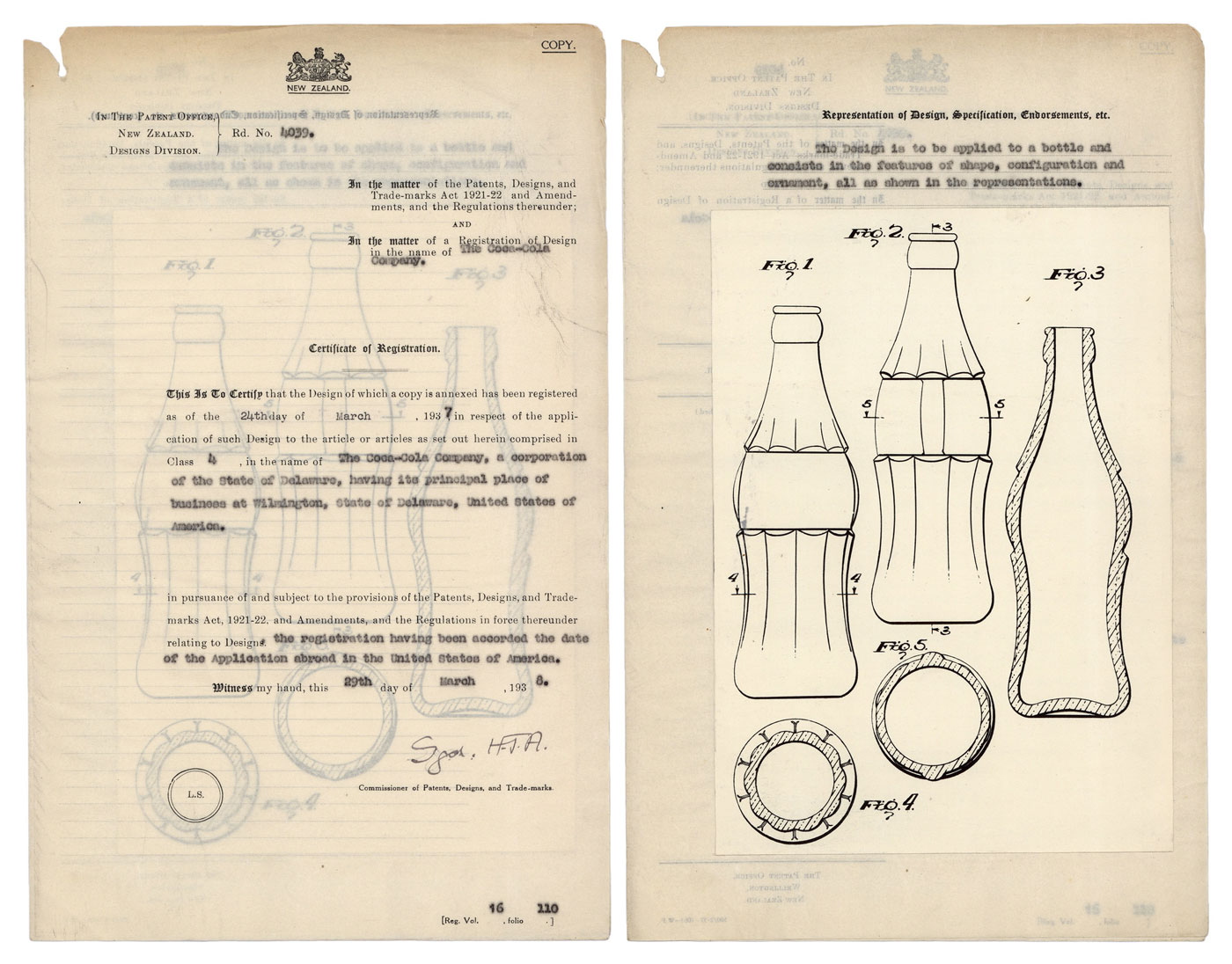

Most of what comes to mind when I think of a brand is in the sensory realm. Colors, fonts, images, logos, videos, sounds, smells, textures, all of these things are used by brands to communicate ideas. In the 1930s and 40s, Coca Cola refined and exploited every sensation — the shape of their glass, the feeling of the carbonation on the tongue, the sound of the bottle opening — to communicate that their beverage was refreshing.

3. Emotions

](https://matthewstrom.com/images/brand-8.jpg)

More recently, companies have focused on the emotions they want consumers to associate with their products. Spotify’s 2015 rebrand by creative agency Collins was almost exclusively geared towards emotion: the bold colors, stark typography, and use of photography all meant to match moments when listeners “cry, cheer, scream, sing, jump, or get chills,” as Collins put it — “burst” with emotion.”2

Words are more concrete than experiences which are more concrete than emotions. But the most successful brands work on all three layers.

Putting it all together

A brand is words, experiences, and emotions that quickly communicate what a company is, how the company works, who the company serves, and why the company exists.

It’s a bit clunky. But it encapsulates the breadth of what a brand is, or at least what a brand can be.

As we do the work of updating SimpleHealth’s brand, it might turn out that this framework isn’t very helpful at all. But I think it’s a good place to start.

Special thanks to Josh Petersel for reviewing an earlier version of this essay.

-

Khan, S.U. and Mufti,O., “The Hot History and Cold Future of Brands”, Journal of Managerial Sciences, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2007, p. 76 ↩