Hi team, Matt here.

Surely you've heard about NFTs, whether you vaguely get the gist, or you've got 'wagmi' in your most recent tweet. I haven't minted or bought any myself, but as someone who loves art and technology, I'm following the meta with keen interest. While Robin Sloan's Notes on Web3 sums up most of my thoughts, I wanted to put together a supplementary piece based on some thoughts I had about the past and potential future. You don't need to know much about NFTs to enjoy it - I hope you do, in fact, enjoy it.

But first, some music. It's hard to describe the allure of "24/7 lo-fi hip hop study beats to relax to;" maybe that's a good essay for the future. Regardless, I'm going to keep on using the endless streams of it on YouTube to fill in empty space ( I wonder what Brian Eno would say?). Here's the mix I'm currently listening to.

Now, on to the essay. As always, you can read it on my website if you like.

ps: Thank you for being a subscriber. I'll send more in 2022, promise.

The legacy of NFTs

A new trend is sending shock waves through the world of art, collecting, finance, and investing.

It’s the result of a perfect storm: one part scientific breakthrough, one part new financial paradigm, one part reflection of world events. Some people attribute it entirely to the current pandemic; only fatalism could explain why normally logical and sane people are cashing out their life savings or remortgaging their homes to buy in.

But for those who are buying and selling, it’s a community. Buyers are willing to pay extra fees to middlemen just to participate in the market. They meet up in private to trade their goods (though, the goods themselves technically don’t go anywhere; the traders are essentially exchanging proof of ownership). The stuff has exotic names that amount to in-jokes; to hear someone talk about the market you’d swear it was another language entirely. It’s a renaissance, and it’s unregulated.

Behind the scenes, creators cash in. In a masterful application of new technology, artisans have figured out how to walk a tightrope between creativity, scarcity, and accessibility. An arms race has ensued: creators “breed” unique assets that, by the nature of their creation, are rare and impossible to reproduce.

There is, of course, a downside: It’s all a massive leech on the environment. The “farmers” that support the market are incentivized to use their resources in what amounts to, at best, a waste of space, and at worst, a cruel act of ecocide.

The whole thing is a public spectacle. Trades make newspaper headlines. Eye-watering prices on seemingly insignificant things make the market a constant topic of debate. People who have never invested in anything are getting into the market. It seems like you can’t go five minutes without hearing about it.

It’s 1630s Holland. Everyone has lost their minds about tulips.

Before 1550, the Dutch had never seen a tulip.

When the Dutch East India Company brought them to Holland from Turkey, the flowers were a popular novelty due to their bright, vivid colors. But cultivators quickly discovered that, under the right circumstances, new colors and patterns of the flowers could be created. New tulips with names like Admirael ("admiral") and Generael ("general") were introduced. Rarer combinations had even more extravagant names, like "Admiral of Admirals" and "General of Generals".

By 1610, ‘tulip mania’ — tulpenwindhandel — was in full swing (so was the bubonic plague in Haarlem, center of the tulip trade). Because tulips take years to grow and multiply, there was a hard limit on the supply of new bulbs. Demand, however, was growing exponentially, and soon prices began to do the same.

At the same time, the Dutch were leading a golden age of innovation in economics, banking, and financing. The introduction of futures markets — where traders bet on the value of assets that haven’t been bought or sold yet — were especially influential in the growth of Dutch commerce. There was, of course, a tulip futures market.

As tulip mania rose to a fever pitch, more and more people got involved in trading. Middle- and lower- class dutchmen who knew nothing about how the markets worked (or how tulips were grown) were investing in bulbs. Buyers and sellers met at taverns where sellers paid a “wine money” fee. The bulbs themselves never traded hands; the ownership of them did via notarized paper records.

The promise of a windfall loomed large in traders’ minds, driving prices higher and higher. Then in 1637, prices suddenly dropped. Investors who had purchased thousands of bulbs, most of which were in the ground and years away from becoming tulips, panicked. Bulbs were dumped into the market for a loss, causing supply to quickly outweigh demand, inverting the market. Tulip mania ended with a bang.

It’s easy to see the parallels between tulip mania and the NFT craze. This New York Times headline from March 2021 sums it up nicely:

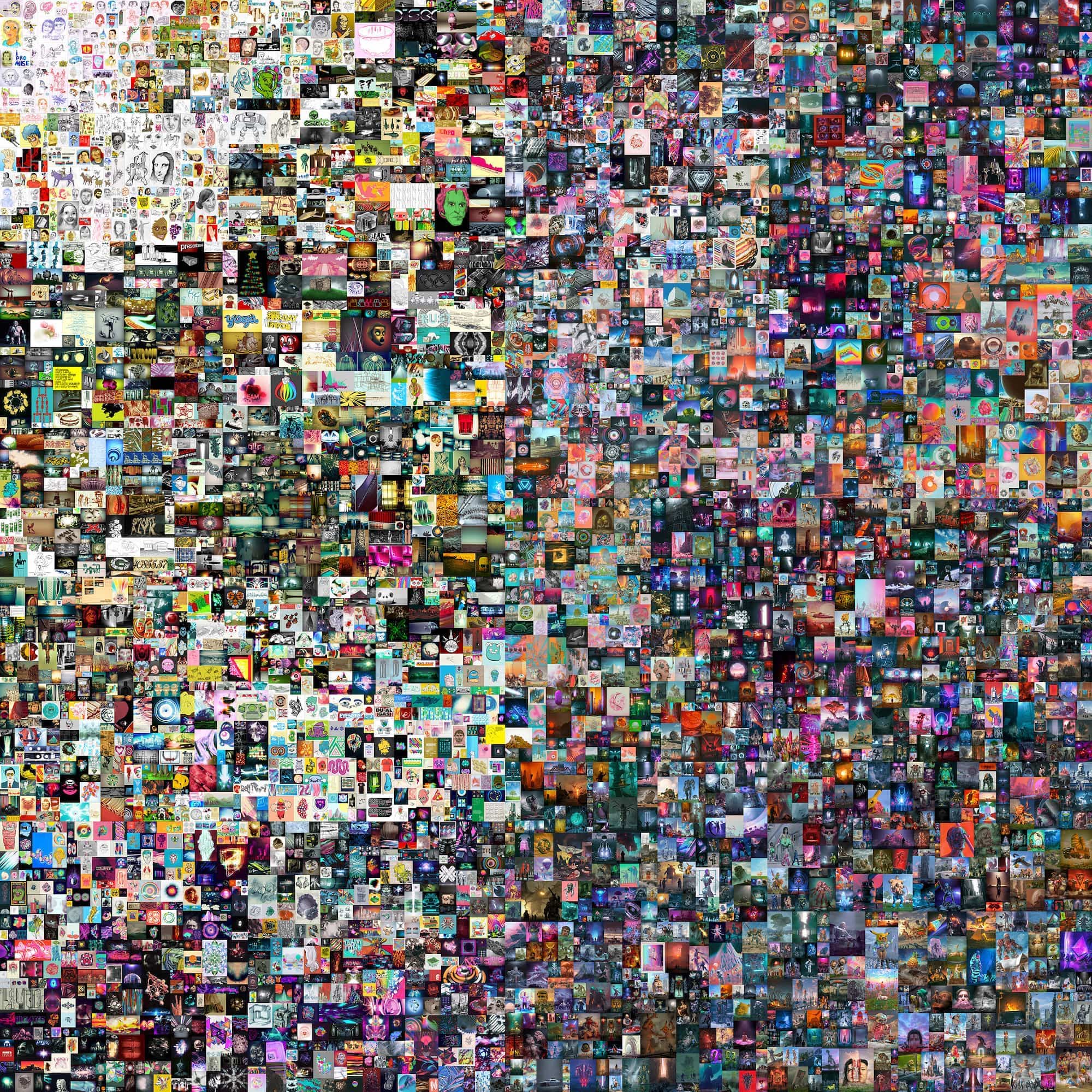

“JPG File Sells for $69 Million, as ‘NFT Mania’ Gathers Pace”

In 2021, $23 billion moved through the NFT marketplace.1 This isn’t that much in the grand scheme of things: $474 billion worth of trades was conducted on Nasdaq, the second largest stock exchange in the world, in just one day.2 But Nasdaq has been around for 50 years; the NFT market has existed for less than 10.

Vast amounts of energy are being poured into minting and staking new NFTs. While accurate estimates are elusive, a recent analysis shows that OpenSea, one of the most popular NFT trading platforms, is responsible for the equivalent of over 600 billion tons of CO2 emissions over the past four years.3

And we’re still on the upswing. The NFT market tripled in 2020 to more than $250 million; then, grew another $200 million in the first three months of 2021. It’s impossible to know where the top of this mountain is or what the slope on the other side of it looks like. My guess is: probably pretty high, and probably pretty steep.

There are as many arguments about NFTs as there are NFTs themselves. They’re pretty bad for the environment — unless you know what you’re doing and use an environmentally-friendly blockchain. They’re often minted without authorization from artists — but blockchains can establish provenance and smoke out illegal copying. They’re a grift, a pyramid scheme, greater fools all the way down — but at least artists are getting paid.

My point in bringing up tulip mania is this: Tulip mania didn’t start the Dutch Golden Age, and it didn’t end it. It was a product of the time. IN 1630, international trade, financial innovation, and class mobility were all at an all-time high. The economic innovations that led the ships of the Duch East India to circle the world were the same ones that led to tulip mania.

Tulip mania may have been the world’s first recorded asset bubble, but it ended up ranking pretty low on the list of the worst economic catastrophes. Likewise, over the long arc of history, NFTs are much more likely to be an amusing anecdote than a watershed or a rubicon.

Like tulip mania, NFTs are a product of their time. It’s become common to see someone list their job as “content creator.” Digital art is coming into its own as a thing you can own, and artists are finding new ways of skirting the predatory system of galleries and private collectors. Cryptocurrency is definitely here to stay, though nobody can quite say where it’s headed. And underneath it all, concepts introduced by blockchains have kicked off a boom in related fields like security, cryptography, and finance.

But the crash will come, and the bubble will pop. And some day someone will buy an NFT for their mom for mother’s day and chuckle, because at one point in the 2020s these things cost an entire year’s salary.