Hi again. It’s me, Matt.

One of the best pieces of public speaking advice I’ve received is deceptively simple: listen. At first blush, listening seems to be the opposite of speaking, right? But that’s the point. Listening — really, really listening — helps you understand how others hear you. The better you are at listening, the better you can be at speaking.

What is the opposite of designing? Can it help me be a better designer? The answers, I think, are 1. Seeing, and 2. Yes. Seeing — really, really seeing — helps you become a better designer.

I wrote this post to help others learn how to see, too.

But first, a song. I’ve been listening to 공중도둑 (Mid-Air Thief) a lot lately. Here’s one of my favorites from his latest record, 무너지기 (Crumbling): 쇠사슬 (Ahhhh, These Chains!)

Now, on to the essay.

(ps: you can also read this on my website, if you prefer.)

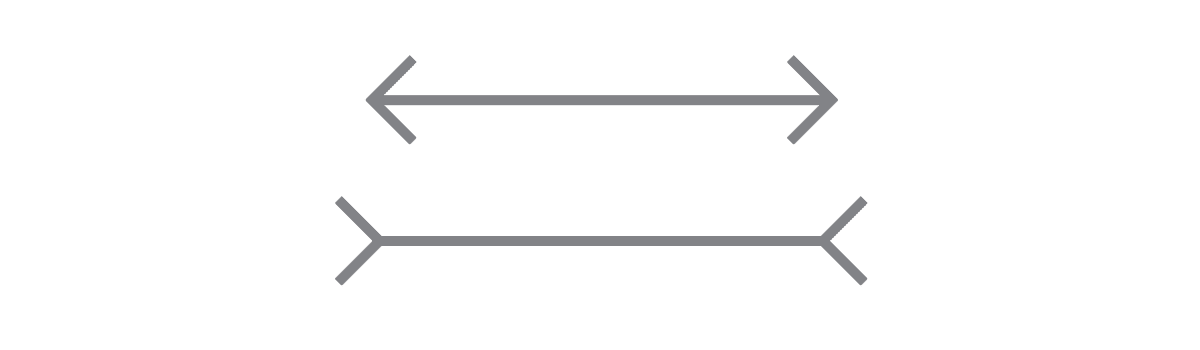

This is the Müller-Lyer illusion. You’ve probably seen 1 it before: it consists of two lines, each with forked ends. The middle portion of the top line looks longer than the middle portion of the bottom line. However, when you measure the length of each middle portion, they are the exact same length.

There are many illusions like this.

Are the shapes in this image moving?

Is there a spiral in this image?

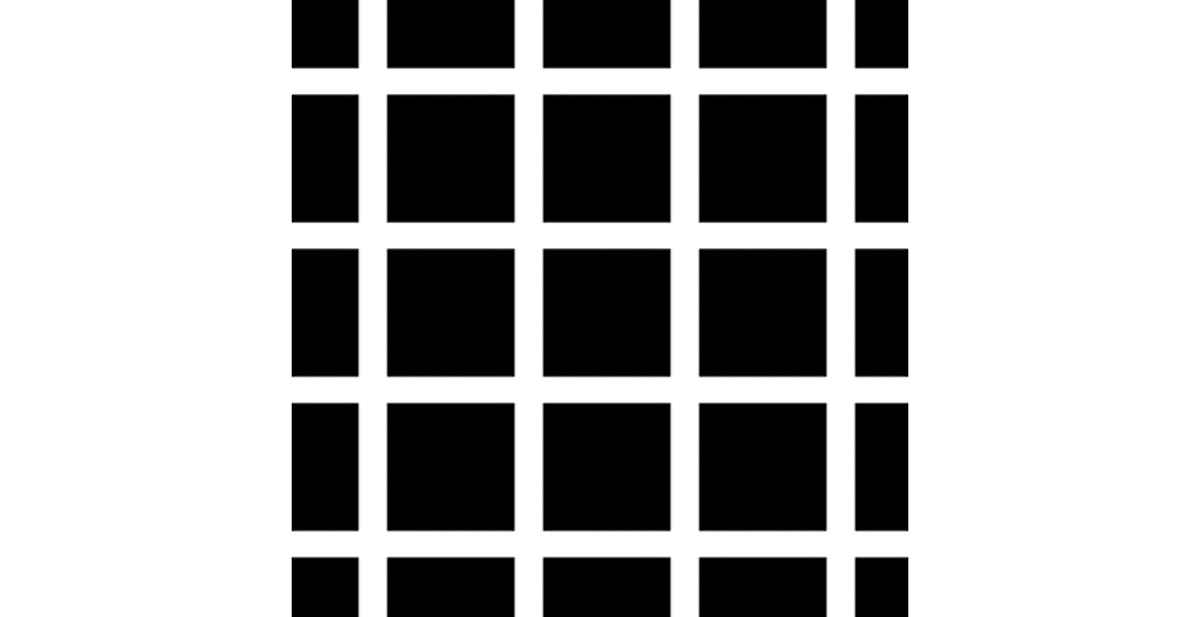

Are there gray dots at the intersections of this grid?

While these pictures are fun to look at, after seeing the first few, you probably aren’t fooled. You’ve learned how to see optical illusions: Even though you see moving shapes, different-sized lines, spirals, and gray dots, you know that none of those things are really there.

The moon illusion

The previous examples are all pretty contrived. They were designed to take advantage of how your brain perceives light and shadow. But there are other, more subtle examples that you experience every day.

Next time you’re outside at night, take a look at the moon. How big does it look? If the moon is near the horizon, it will look relatively large and close. When it’s high in the night sky, it will look small and far away.

But no matter where it is in the sky, the moon is always the same apparent size2 — if you held a ruler at arms length, it would measure the same throughout the night! You don’t even need ruler to check: take a sheet of paper and roll it up into a narrow tube. Point it at the rising moon and adjust the tube’s size until it’s a little larger than the moon’s diameter. Tape the tube so it stays the same size and look at the moon again a few hours later. You’ll see that it fills the same space.

Today, we have satellites, sophisticated ground-based telescopes, and human expeditions to space to measure the moon’s size. But early astronomers like Copernicus and Newton didn’t have that technology. They had to rely on the naked eye to make accurate estimations of the moon’s size. They used these simple observations to predict the moon’s orbit; learning how to see was a major breakthrough.

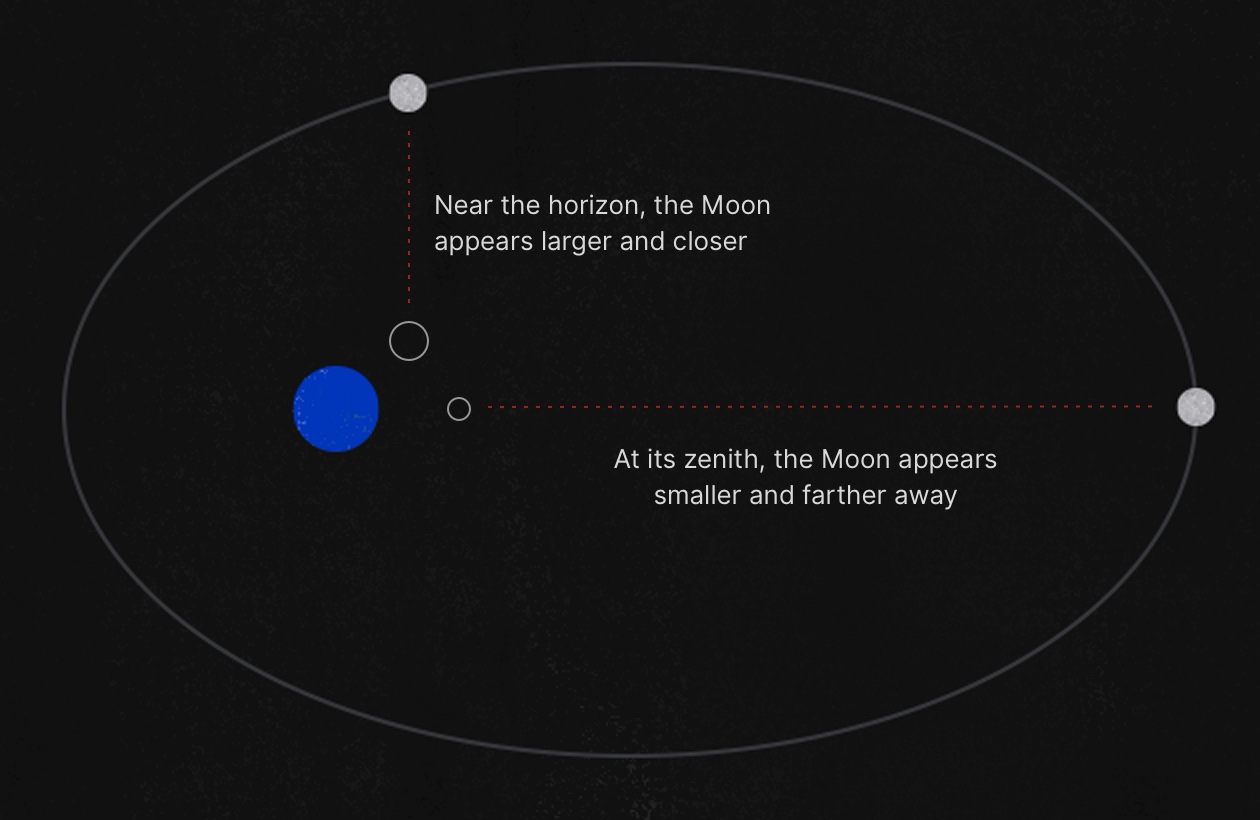

If Copernicus and Newton believed their intuition — that the moon’s apparent size changes throughout the night — they would conclude that the moon is closer to the earth at the horizon, and farther at its zenith (the highest point of its arc). Its path through space would be an ellipse:

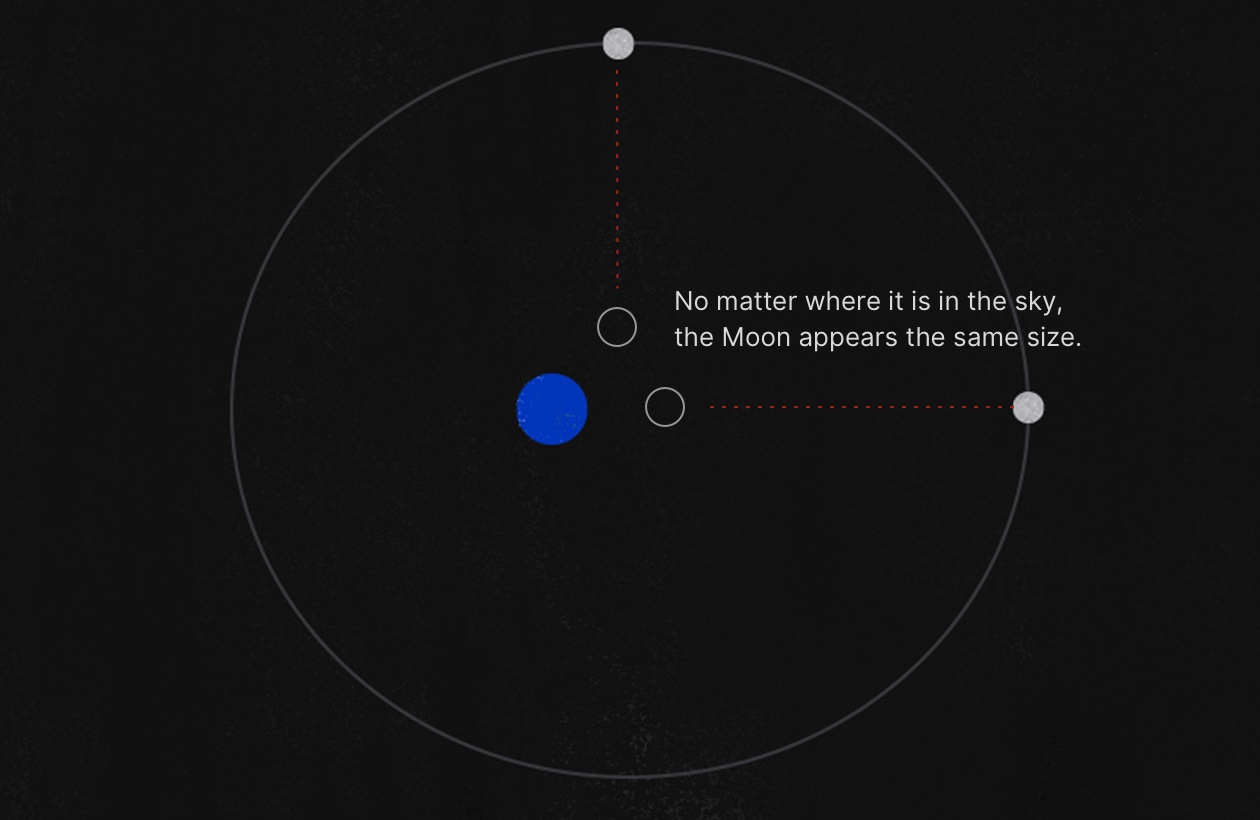

However, the moon’s apparent size doesn’t change. This means that the moon is nearly the same distance from the earth throughout its arc. It’s orbit is closer to a circle:

Knowing that the lunar orbit was circular (and not elliptical, as it first appears) was the key to understanding how the moon interacted with the Earth’s oceans to create the tides. After learning how to see the moon’s orbit, scientists could make accurate forecasts of high and low tide (useful for shipping goods) and create accurate calendars (useful for planning military maneuvers).

How designers see

These phenomena show the difference between merely seeing things and knowing how to see things. There are lots of things that you see every day that you merely see; there are some things you’ve learned how to see.

This is how professional creative workers (digital product designers like me, for example) do our jobs. We don’t have a mystical sixth sense, some X-ray vision that allows us to access hidden insights and information. Through thousands of hours of experimentation and study, we’ve learned how to see the kinds of things we are asked to design.

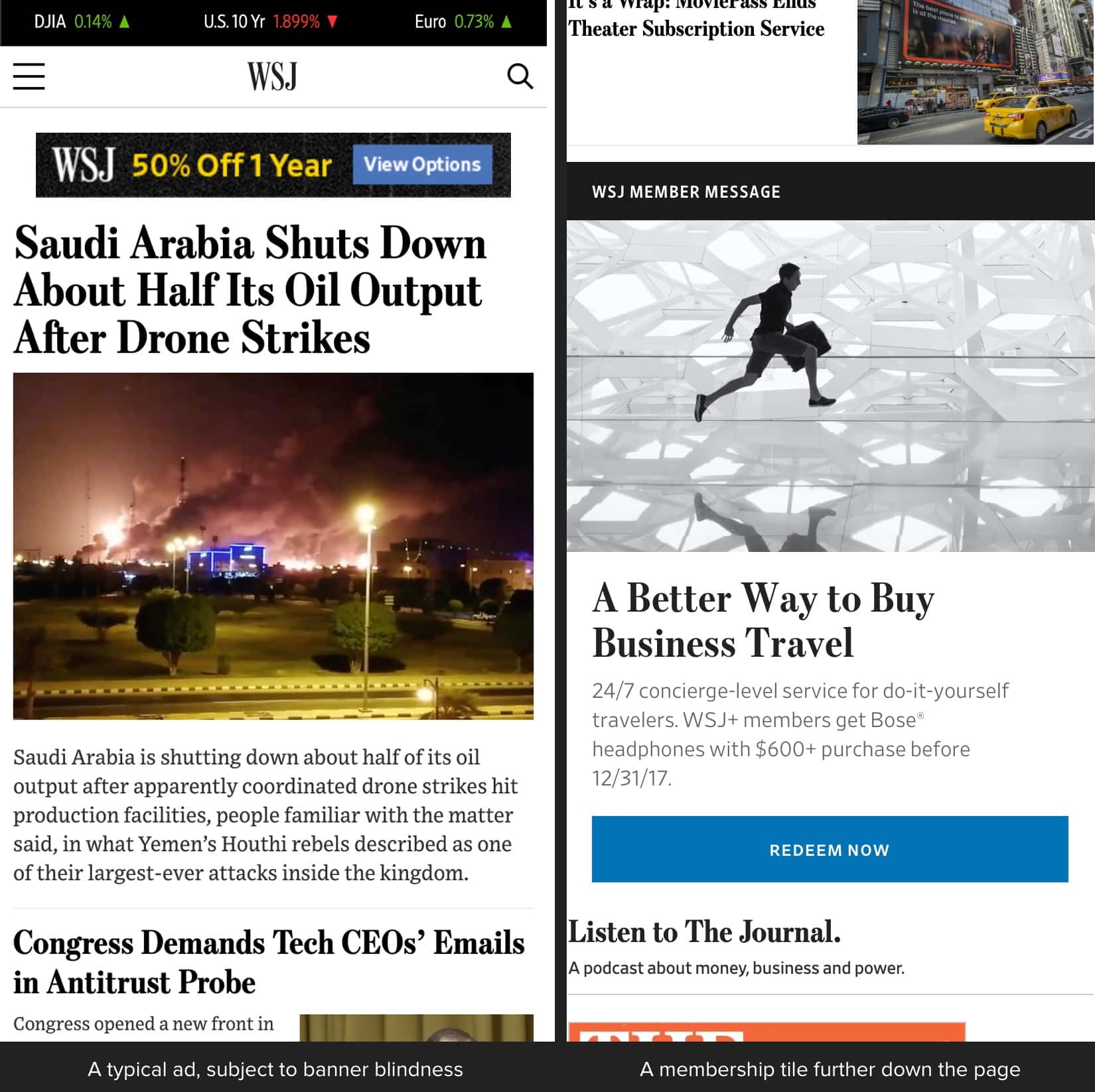

Take websites, for example. The average person sees nearly 100 pages every day3. Despite such familiarity, the average person hasn’t learned how to see websites. Their impressions and beliefs of web design are susceptible to bias, such as banner blindness. Banner blindness is the phenomenon where website visitors subconsciously ignore content in certain positions (at the very top or in the rightmost column) or sizes (wide rectangles) because they resemble advertisements.

My experience as the design director of wsj.com taught me how to see websites through the lens of banner blindness. Advertisers often wanted their ad to be placed in a prominent position at the very top of the homepage, assuming that would get the most attention. However, I knew that other, smaller placements further down the page performed better. One treatment in particular, called a membership tile, was our best-performing ad day after day; it was placed near other articles to avoid the banner blindness effect.

Despite my knowledge and experience, and even armed with the data to back up my claims, it was still difficult to convince stakeholders of banner blindness. It was like telling someone that the moon is the same apparent size throughout the night.

How to learn how to see

Knowing how to see is a valuable but overlooked skill. No matter what it is you do for a living, learning how to see will improve your ability to make judgements and do impactful work. And it’s really quite simple:

Ask the stupid questions.

What we initially think are stupid questions often turn out to be informative and worthwhile. Asking them gives us the opportunity to explore and learn from conventional wisdom, and helps us take nothing for granted.

For example: why are links on the internet usually blue?

Seek multiple explanations.

It’s tempting to take the first plausible explanation of an observation as the truth. But don’t be content with a single story. By finding other explanations, you’ll either strengthen your initial understanding or discover an even better line of reasoning.

Maybe links are blue because an engineer creating the first web browser thought it should be blue, and that was enough to create a standard. But maybe they’re blue because decades of research has shown that blue is the color that our brains can locate fastest on a colorful page.

Challenge your own assumptions.

The biggest difference between merely seeing from knowing how to see is understanding that our brains can (and often do) deceive us. That means that our assumptions are wrong much of the time. Being willing to be wrong — that is, being humble about our beliefs — makes it easier to replace seeing with knowing.

Originally, links were blue simply because the early developers of browsers thought it looked good4. But accessibility research has shown that blue is, in fact, a good color for links. Joe Clark explains in Building Accessible Websites:

“Red and green are the colors most affected by color-vision deficiency. Almost no one has a blue deficiency. Accordingly, nearly everyone can see blue, or, more accurately, almost everyone can distinguish blue as a color different from others.”

Links on the internet have remained blue by default, but most designers and developers aren’t just following tradition. They understand the important accessibility concerns of technology, and constantly revisit defaults to create the best experience for the most users.

Conclusion

We spend most of our day perceiving taking in far more information than we can reasonably process without some shortcuts. For the majority of what we see, it’s ok to just see, to take things at their face value. But take time to learn how to see some of what you experience. You’ll be able to make better decisions, share deeper insights, and overall, enrich your understanding of the world around you.

-

I use the word “seeing” throughout this essay in the sense of “perceiving”; not everyone experiences the world through vision. ↩

-

The moon’s apparent size does change very slightly (up to 13%) over the course of a month due to the shape of its orbit. This change is negligible in the course of a single evening. More information can be found at this page. ↩

-

This number is surprisingly hard to estimate. The best I could find is this 2010 reference to a Nielsen survey: https://web.archive.org/web/20100619070613/http://www.visualeconomics.com/how-the-world-spends-its-time-online_2010-06-16/ ↩

-

Why Hyperlinks Are Blue (and Other Quirky Web Origin Stories)

The road to post-Owl Google from the World Wide Web project isn’t straight. But it does have some fascinating insights into how our online world took on its present shape.