March 3, 2023, 10:48 a.m.

Design-by-wire: How AI will shape designers, not replace them

matthewstrom.com

Hi there, Matt here.

There are a lot of hot takes about AI and design. Brad Frost explored how AI could create product experiences from design systems. Mills Baker warns of a coming winter of design discontent. And Budd says it’s the end of design as we know it.

I’m slightly more optimistic, somewhere between a GPT Luddite and an AI Pollyanna: new tools and technology will challenge designers to evolve, but will ultimately result in more efficiency, more impact, and more opportunities for designers to innovate. That’s what today’s essay is all about.

Before we dig in, some tunes. Awesome Tapes from Africa has always been on my radar as a source of great music. But when I heard the few bars of the first song on Hailu Mergia’s “Tezeta,” I immediately bought the record. The loping, pleasant funk, the chorus of horns, and Mergia’s virtuosic (but not alienating) organ playing all come together for a mood-boosting 40 minutes.

Now, on to the essay. As usual, you can read it over on my website, too.

Design-by-wire

How AI will shape designers, not replace them

There’s a lot of fear in the air. As AI gets better at design, it’s natural for designers to be worried about their jobs. But I think the question — will AI replace designers? — is a waste of time. Humans have always invented technology to do their work for them and will continue to do so as long as we exist.

Let’s use our curiosity and creativity to imagine how technology will help us be better, more efficient, and more impactful.

So, in that spirit, I’d like to share a metaphor that I think paints a picture of how the job of design will change in the next decade.

Flying by wire

Commercial airplanes are some of the most complicated machines humans have ever built.

It took all of Wilbur Wright’s skill to fly the first powered airplane for a minute, just 10 feet off the ground. That plane, the Wright Flyer, could carry one person; it weighed 745 pounds with fuel and could reach a height of 30 feet at a maximum speed of 30 miles per hour.1 The Airbus A380, currently the world’s largest commercial airliner, weighs over a million pounds when fully loaded. It can carry up to 853 people, flying up to 43,000 feet at a cruising speed of 561 mph — 85% the speed of sound. Just two people pilot the A380.2

, [CC BY 2.0](https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23313866)](https://matthewstrom.com/images/design-by-wire-1.jpg)

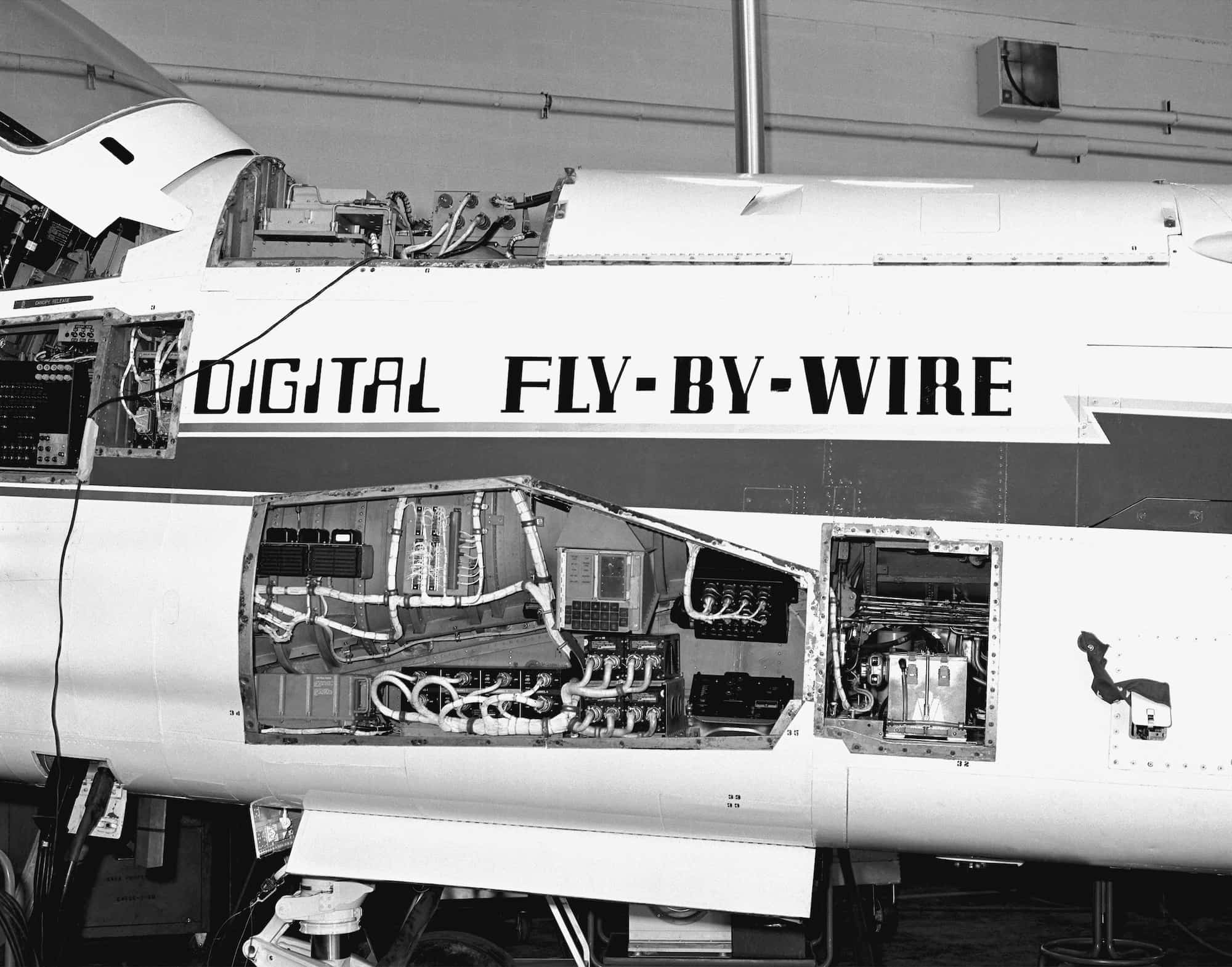

The A380, and all modern commercial airplanes, wouldn’t exist without something called “fly-by-wire.” Fly-by-wire is a system that translates a pilot’s inputs — changing the throttle to speed up or slow down, controlling pitch and roll with the yoke, turning knobs and dials in the cockpit — into coordinated movements of the airplane’s engines and control surfaces. The first fly-by-wire systems were a veritable nervous system of electric relays and motors; today, they’re sophisticated computers in the belly of the plane.

Originally, fly-by-wire had nothing to do with automation. As airplanes got larger, the cables, rods, and hydraulic links connecting the cockpit to the rest of the plane became a monumental design challenge. By replacing those complex, bulky components with electrical wires and switches, airplanes would be lighter and easier to maintain, with more room for passengers and cargo.

The first commercial airplane with a fly-by-wire system was the supersonic Concorde jet. At speeds of over Mach 1, it would be almost impossible for a pilot to move the control surfaces of the airplane through sheer mechanical force; fly-by-wire allowed pilots to smoothly operate the plane at any speed. And because sudden changes at top speed could be catastrophic, the fly-by-wire system could use analog circuitry to smooth out a pilot’s inputs.

As fly-by-wire systems became more common, they went from faithfully transferring pilot’s inputs to interpreting and adjusting them. The Airbus A320, introduced in 1988, featured the first digital (computerized) fly-by-wire system; it included “flight envelope protection,” a system that prevents pilots from taking any action that would cause damage to the airplane. Depending on the speed, altitude, and phase of flight, the fly-by-wire system will ignore certain pilot inputs altogether.

Fly-by-wire has been the focus of both scrutiny and praise since its introduction. On one hand, it has saved lives: When US Airways Flight 1549 (an Airbus A320) flew through a flock of birds on takeoff, it lost all power. The pilots had to make an emergency landing in the Hudson river, flying the airplane unusually low and slow, risking putting the plane into an uncontrollable stall. The fly-by-wire system, with its flight envelope protection, ensured the plane could maneuver at the very edge of its capability, leading to a controlled landing with only a few serious injuries for those aboard.

On the other hand, fly-by-wire has been criticized for replacing parts of pilots’ expertise. In 2009, Air France Flight 447 (another Airbus A320), crashed in the Atlantic Ocean, killing all 228 passengers and crew. An investigation into the cause of the crash concluded that the autopilot and fly-by-wire protections started to malfunction when ice crystals interfered with the aircraft’s sensors; the pilots, used to flying with the safety of flight envelope protection, couldn’t correct for the errors, stalled the plane, and crashed into the ocean.

Whether you think fly-by-wire is a crucial innovation or a crutch, its effect on the airline industry is easy to demonstrate. Bigger planes that fly farther can carry more passengers to more destinations. From 1970 to 2019, the number of airline passengers worldwide has grown over 1,400%, from 310 million to 4.4 billion.3 In the same time period, the number of commercial pilots — pilots holding “commercial” or “airline transport” licenses — has increased 27%, from 208,027 in 1969 to 265,810 in 2019. Pilots’ salaries have stayed consistently high: an average airline captain made about $51,750 a year in 19754, the equivalent to $287,770 in 20235. An airline captain with six years of experience can expect to make $285,460 today.6

Designing by wire

Just as fly-by-wire systems have made pilots more efficient (not redundant), AI and automation will make designers more effective.

Imagine a design-by-wire system. The job of the designer is to indicate what they want the desired outcome to be. Like a pilot pushing the throttle to make the airplane accelerate, a designer could assemble a wireframe or configure a screen to enable a user to accomplish a task. The design-by-wire system could then interpret the designer’s instructions.

- The system could change aspects of the design to use the latest design systems components in the correct way.

- The system could optimize the design to make implementation cheaper, faster, or less prone to bugs.

- The system could automatically fix accessibility issues, or add information to address accessibility concerns like keyboard shortcuts, screen reader labels, or high-contrast and reduced-motion variations.

- A designer could list out hypotheses about the design (like “will this convert the most users to paid plans?”), and the system could provide designs for multivariate testing, along with test or research plans.

- The system could automate QA by testing designs against simulated user behavior, adjusting the designs to cover the wide and unpredictable cases of real user interaction.

You can already see these kinds of systems taking shape. Noya promises to take wireframes and turn them into production code using an existing design system. Galileo AI claims to be able to create fully-editable designs from a single text description. Diagram’s Genius aims to provide contextual suggestions in Figma, filling out designs with the click of a button. These are just early tech previews, but they paint a picture of AI becoming a core component of our design tools.

At the end of the day, design-by-wire systems are centered around the designer. Like the pilot of an Airbus A380, the designer becomes the operator of a fantastically complicated machine.

There is a risk in designing by wire. If designers don’t understand how the system works, they risk losing control, becoming less effective than they were before. That’s why it’s important that we become experts in AI; we don’t have to be able to write the code that drives these tools, but we need to understand the way the systems work.

To use the machine to its full potential, the designer has to understand the intricacies of its operation: Pilots, by analogy, train for years in simulators before they step foot in the cockpit of a real airliner. Here’s a few resources you can use to learn more about GPTs, the systems driving the current boom in AI:

- Stephen Wolfram’s “What is ChatGPT Doing … and Why Does It Work?” is an incredibly in-depth exploration of the technology and concepts, with interactive code.

- Ted Chiang’s “ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPEG of the Web” uses analogies to explain the strengths and weaknesses of GPT technology.

- 3Blue1Brown has a 5-part video series explaining the basics of neural networks, including how they are trained.

- The Coding Train has 26 videos on neural networks, in which Daniel Schiffman builds and explains various components and variations of neural nets. There’s also an accompanying chapter in Schiffman’s book The Nature of Code.

All four of the above authors are amazing teachers who mix mathematical depth with intuitive analogies and mental models.

Conclusion

AI will change our jobs in ways we can’t imagine.

This has been happening to airline pilots since the advent of fly-by-wire systems. In the transition to newer, faster, larger, and more efficient airplanes, pilots have needed more and more technical understanding and skill in interacting with the computers that fly their planes.

But pilots are still needed. Likewise, designers won’t be replaced; they’ll become operators of increasingly complicated AI-powered machines. New tools will enable designers to be more productive, designing applications and interfaces that can be implemented faster and with less bugs. These tools will expand our brains, helping us cover accessibility and usability concerns that previously took hours of effort from UX specialists and QA engineers.

It’ll take years of training to become an expert at designing with these new AI-powered systems. Start now, and you’ll stay ahead of the curve. Wait, and the challenge won’t come from the AI itself; it’ll be other designers — ones who are skilled at AI-powered design — who will come for your job.

-

“Wright Flyer.” In Wikipedia, February 19, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wright_Flyer&oldid=1140234161. ↩

-

“Airbus A380.” In Wikipedia, February 10, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Airbus_A380&oldid=1138648822. ↩

-

“Top 15 Countries with Departures by Air Transport - 1970/2020 -.” Accessed February 20, 2023. https://statisticsanddata.org/data/top-15-countries-with-departures-by-air-transport-1970-2020/. ↩

-

“Industry Wage Survey. Scheduled Airlines.” Scheduled Airlines, Bulletin / Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1977 1972, 2 v. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009881222. ↩

-

Calculated with https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1975?amount=51750 ↩

-

“Major Airline Pilot Salary: First Officer and Captain Pay in 2023 / ATP Flight School.” Accessed February 18, 2023. https://atpflightschool.com/become-a-pilot/airline-career/major-airline-pilot-salary.html. ↩