Hello again, Matt here.

Often the most interesting ideas are the ones that are easiest to summarize. Case in point: two weeks ago I wrote a 6-word tweet about the next evolution of design systems.

I immediately got a few responses expressing interest in the topic. Six words very quickly turned into two thousand. I’m very excited to share the essay with y’all.

But first, a song.

Malibu Entropy by Rips is such a short, sweet, surfy tune. It’s got Ride written all over it, but stands on its own with a few catchy hooks.

Now, on to the essay. This one’s a little long, so you’ll have to head to my website to read the whole thing.

Design systems enable designers and developers to quickly create quality software on a massive scale. As the needs of software-driven businesses grow even larger, design systems are evolving — they are beginning to look and work like APIs.

In software development, “API” stands for “Application Programming Interface.” An API is a reliable way for two or more programs to cooperate. It allows programs to work together despite differences in hardware, language, architecture, or other operating constraints.

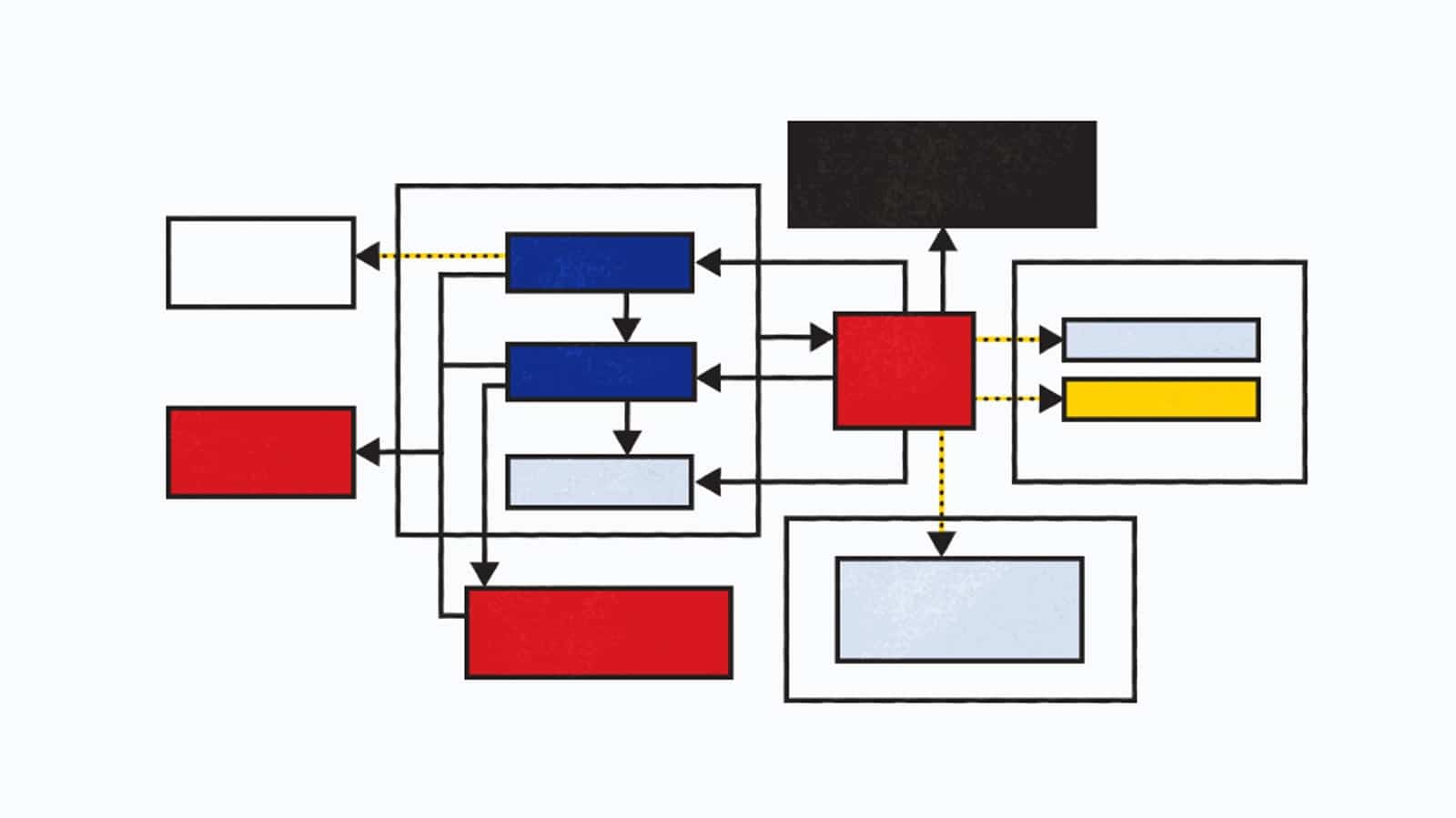

APIs power the internet. They are so powerful because they embody a contract: system A promises to act in a predictable way, as long as system B requests that action in an agreed-upon way. Say system A is PayPal and system B is Etsy: PayPal promises to make a transaction between two bank accounts (a buyer’s and a seller’s), as long as Etsy requests that transaction formatted in a secure and trustworthy way with permission from its users.

As long as these contracts are in place, Etsy and PayPal can write and re-write their own systems without needing to check in with each other. They can work independently and efficiently, according to their own needs. A reliable API creates trust and drives cooperation.

The API model is the perfect match for communication between designers and developers.

A Pseudo-API

If you’re a designer or developer, there’s already an API layer between you and your counterparts. That API might not be well-documented or consistent, but it forms the basis for your communication with each other.

For instance, at Bitly (where I work), designers provide information about design decisions in the form of Sketch files in a tool called Abstract. We’re working with engineers to make sure the format works for everyone as an efficient and accurate way to share specifications.

These standards and informal working agreements look a lot like the beginnings of an API. But our documentation doesn’t look much like a typical API’s documentation (for an example of a well-documented API, see Stripe’s API reference). The design team hasn’t listed any endpoints. There are no sample requests to learn from, or expected return values to test against. Our pseudo-API doesn’t have an uptime guarantee, a service-level agreement, or rate limits. It also don’t fail very gracefully. When something goes wrong, no errors are thrown, and nobody’s pager goes off.

A small team can work through this uncertainty without losing much productivity. But as a team grows, it needs a clearer contract between designers and developers.

Design Systems

Design systems have become an essential tool for fast-paced application development teams. A good design system provides some of the documentation developers need in order to get information about what they are building. Like an API, a design system is an abstraction. An API abstracts some of a program’s functionality; a design system abstracts some of the design process.

Companies like Salesforce have led the way in implementing large-scale design systems. Salesforce has thousands of developers and designers working on features across many platforms and applications. To enable this kind of work at scale, the team collaborated to produce a design system called Lightning.

Lightning is a contract. On one side, it outlines very specific ways for developers to mark up their code to ensure the user experience is delivered consistently. For instance, a developer agrees that they’ll use a specific style of markup:

<button class="slds-button">Button</button>

In return, Lightning guarantees that this button will have the proper appearance and functionality. It will meet Salesforce’s standards of usability and accessibility.

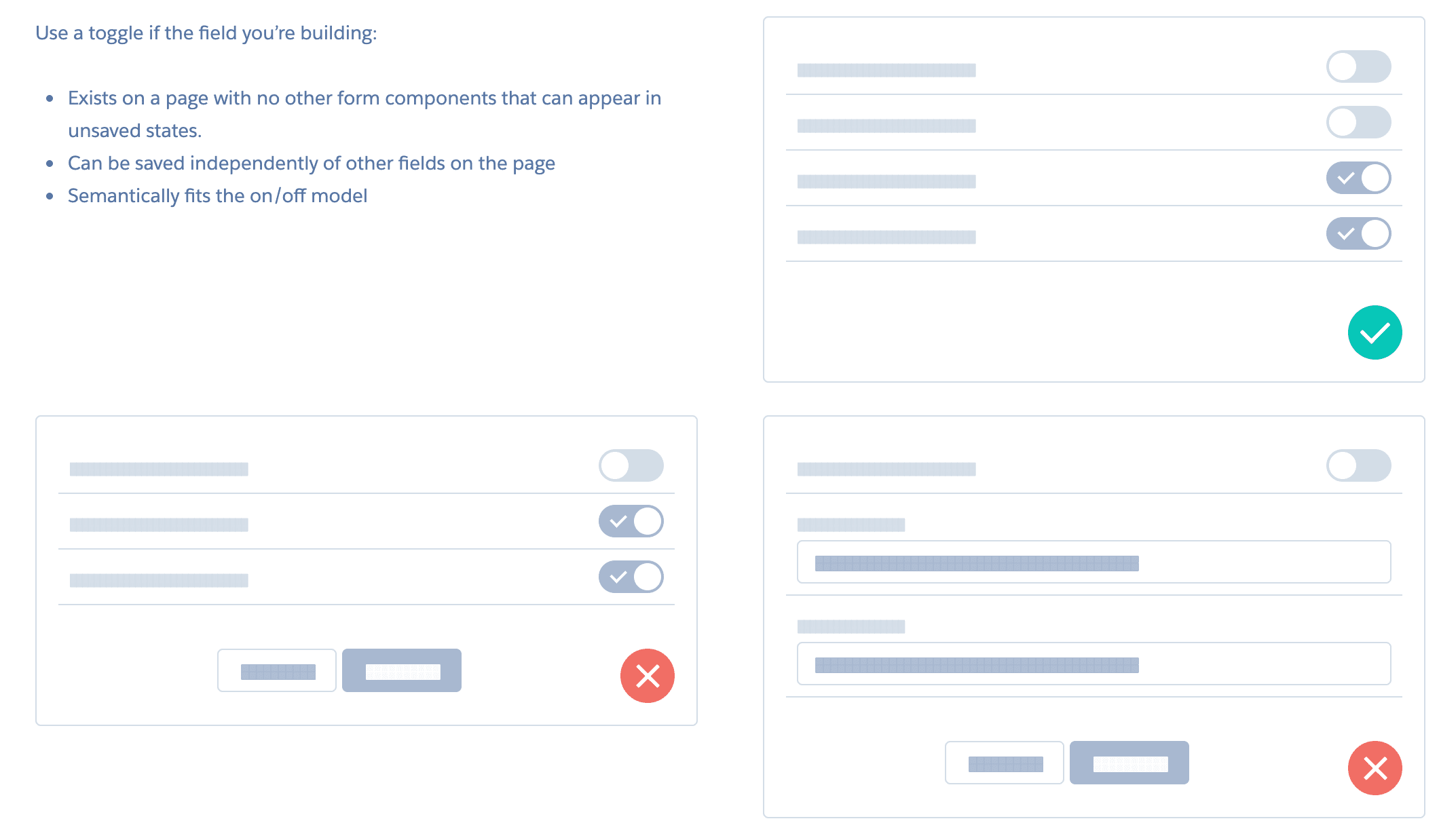

On the other side of the contract, Lightning specifies rules for creating or modifying design specifications. For instance, a designer agrees to follow guidelines for using toggle switches in forms:

In return, Lightning promises that these design decisions will be delivered quickly to end users with fidelity and integrity. The application will continue to meet Salesforce’s standards of performance and reliability.

The Problem with Design Systems as APIs

Lightning works for Salesforce, but it requires a dedicated team of engineers and designers. The design system team is solely responsible for Lightning’s continued performance: they maintain the documentation, educate users, evangelize for adoption across the organization, and monitor how the system is working.

A dedicated design system team is required because a design system is only a low-level abstraction of the design process.

This means the design system’s documentation — the website or wiki or design file that describes it — is its most useful application. For instance, the easiest way to use the colors Lightning provides is to visit the ‘Colors’ page on Lightning’s website.

Think of this like a phone book. A phone book is a low-level abstraction of a phone number directory. To find someone’s number, you flip through the pages of the phone book until you find their name. A whole team of people produces the phone book, printing and distributing it on a regular basis to ensure it is up to date.

Adding one level of abstraction to a phone directory means removing the printed book from the equation. Instead of flipping through pages, a user types a name into a search box and instantly sees that person’s phone number. The number can be kept up to date without reprinting a hefty book. Other programs can read this information, too: Integrations to messaging apps might mean the end user never needs to see the phone number at all.