On Gribley's Mountain

How a children's book from 1959 taught me to love the wild

I always experience a certain trepidation in revisiting favorite books from childhood. If they don’t hold up to my mature tastes, I feel like I have lost something, or like something I believed in has ceased to compel my assent. The experience is doubly fraught when I’m introducing my old favorites to my own children, whose tastes can and do diverge from my own. We’re just reading a book, but suddenly my whole childhood hangs in the balance.

I had one such experience introducing my sons to Jean Craighead George’s 1959 novel My Side of the Mountain. Mercifully, the book—one of my absolute favorites from childhood—did indeed hold up. More than that, it caused me to reflect upon how literature, perhaps especially children’s literature, can help us see and know the world around us. Accordingly, I’m writing now in appreciation of the book, not because it was necessarily my sons’ favorite read or because it’s a perfect book, but because I think it is a book that can help us make a habitation where we are.

Like a lot of boys, I went through a sustained period of fascination with wilderness survival stories when I was maybe eleven years old. I read Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet, Call it Courage by Armstrong Sperry, and even a practical manual of survival skills. Using Euell Gibbons’ Stalking the Wild Asparagus as my guide, I prepared a wild-foods meal for my family, featuring daylily buds, candied acorns, trout lily bulbs, and roasted dandelion root coffee.

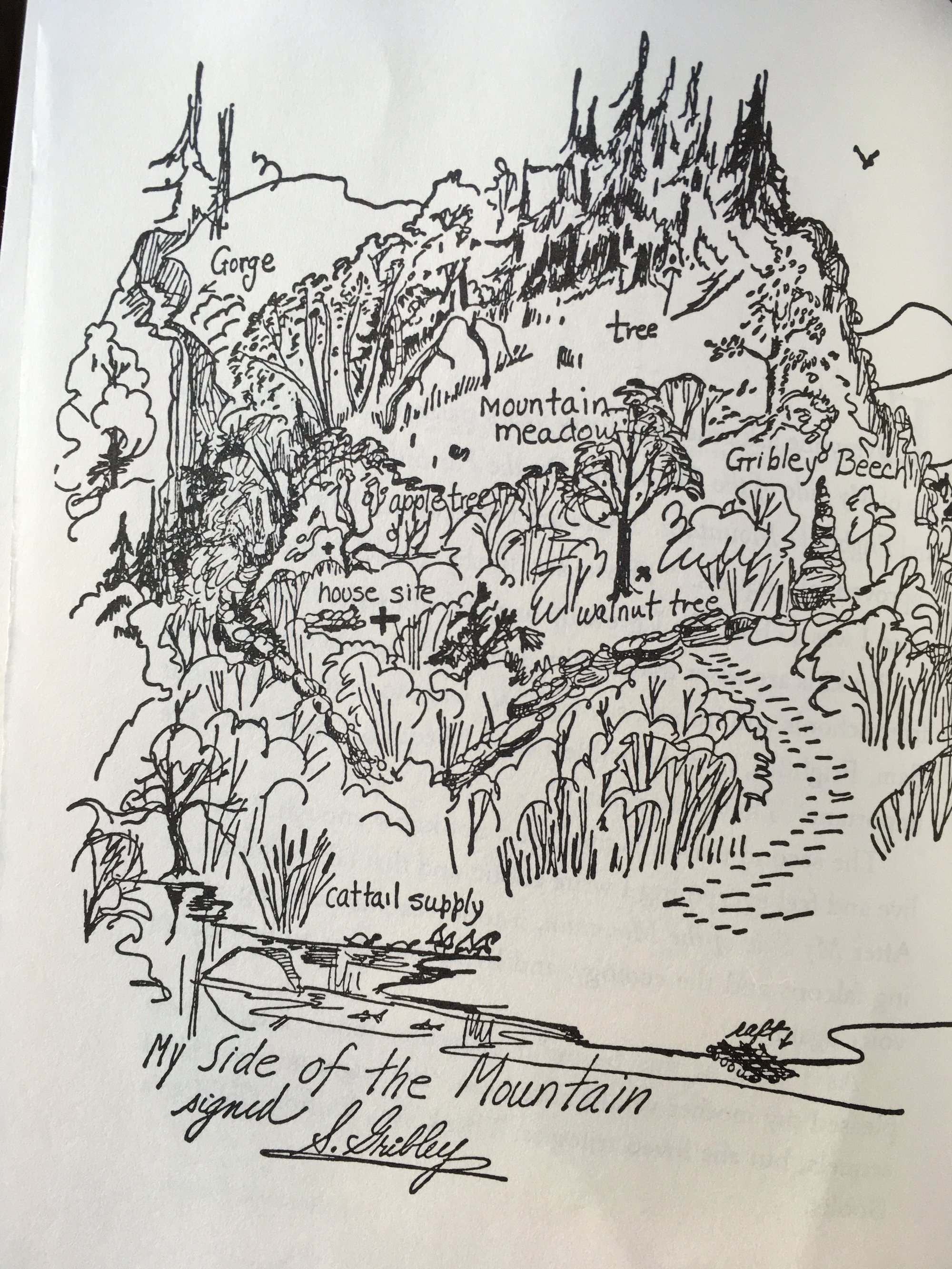

My Side of the Mountain, though, was my favorite. The novel tells the story of how teenage Sam Gribley runs away (with his father’s permission) from his New York City apartment and settles into the wild on a mountainside in the Catskills. Sam has studied up on survival skills before he departs, yet the novel requires one big suspension of disbelief from the reader: that a teenager who has read the right books could feed and shelter himself alone in the woods for a year. Such a suspension being made, the book blends technical knowledge of survival skills with all the beauty and thrill of the woods. Consider the opening paragraph:

I am on my mountain in a tree home that people have passed without ever knowing that I am here. The house is a hemlock tree six feet in diameter, and must be as old as the mountain itself. I came upon it last summer and dug and burned it out until I made a snug cave in the tree that I now call home.

Nothing could be more romantic. Nothing could be more attractive to an outdoorsy child than this vision of a secret tree house, made by one’s own hands and undetectable by bigger folks.

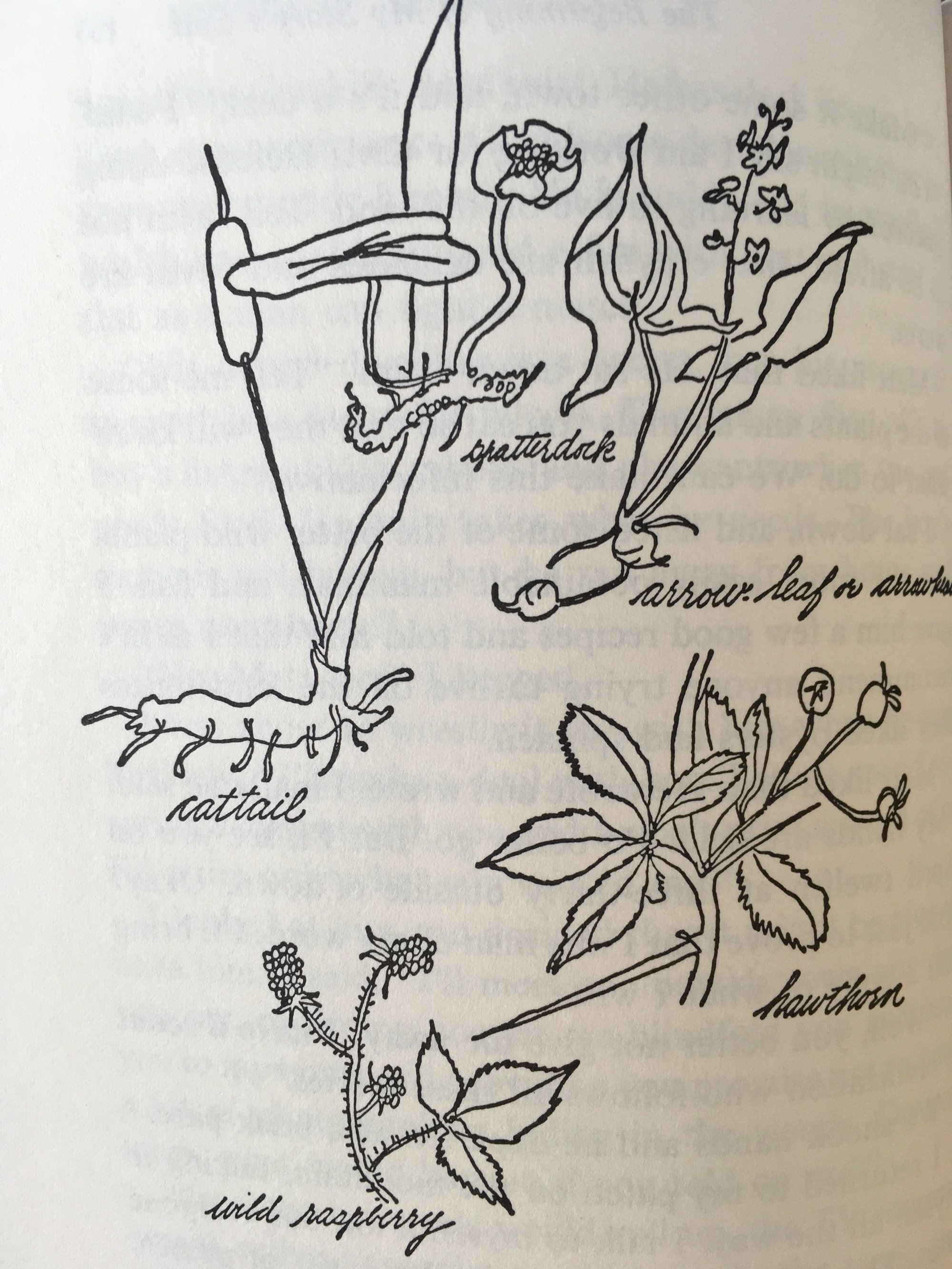

Sam starts a fire with flint and steel; makes his own tools, lodging, and clothing (from buckskin); forages for wild vegetables, fruits, and mushrooms; catches fish and traps game; and, most spectacularly, captures and trains a peregrine falcon to hunt for him. George is a good naturalist and survivalist herself, and suffuses the book with wonderful details, even including some of Sam’s favorite recipes:

Brown puffballs in deer fat with a little wild garlic, fill pot with water, put venison in, boil. Wrap [cattail] tubers in leaves and stick in coals. Cut up apples and boil in can with dogtooth violet bulbs. Raspberries to finish meal.

Her own illustrations, rendered in the precise style of a field guide, appear throughout the text. Between her account of Sam’s woodsmanship and the illustrations, I learned a lot about the wild from the book, perhaps even more than I did from the manuals and field guides I read alongside it. My Side of the Mountain taught me to look at the world with care and attention and see not just a tree or a flower, but a hemlock or a dogtooth violet. And yet the book provides this information lightly, in a laconic style that mimics well the naïve perspective of a young boy, never loading the reader down with the self-serious contention that these are Facts You Need to Know.

The narrative and prose style of the work, then, perhaps especially make My Side of the Mountain a work that encourages a close attention to the world. It’s something of a misnomer to call the book a survival story, because Sam is never really in any danger. His first night in the woods is rather uncomfortable—he’s cold and hungry after failing to catch a fish or build a good shelter—and after that his brushes with danger are mild, and depicted as ordinary struggles of life rather than looming narrative threats. Moreover, though Sam runs away from home and adult civilization, he’s never truly in conflict with the adults in his life: his parents encourage him to “run away,” saying every boy should try it once, and the other adults he encounters in the Catskills are uniformly kind and helpful. Accordingly, it’s a gentle, even undramatic book that draws all its excitement from the romance and the particularity of Sam’s life in the woods rather than from narrative tension or dramatic conflict.

You might think that lack of dramatic anxiety would make it a boring book. But I never found it so, and neither did my sons when I read it to them. Instead, Sam’s calm and pleasant experience in the woods made me dream of living like he did. I’m reminded here of a great essay by Lauren Wilford on the Hayao Miyazaki film My Neighbor Totoro, which Wilford calls a “true children’s cinema”:

My Neighbor Totoro is a genuine children’s film, attuned to child psychology. . . . [The film] follows children’s goals and concerns. Its protagonists aren’t given a mission or a call to adventure—in the absence of a larger drama, they create their own, as children in stable environments do. They play.

In My Side of the Mountain, Jean Craighead George makes the wild a place where children can imagine themselves safe, knowledgeable, and able to play. Accordingly, the book is a true children’s literature, a work that helps me and my sons alike to look, see, and enjoy.

If you enjoyed this essay, you might also like my book of garden essays, linked below. Thanks for reading.