In Praise of the Blockquote

I, too, dislike them—but...

Writing is selection. - John McPhee

Nobody reads your blockquotes. By their length and visual weight, they tempt readers to skip them altogether. At best, they weigh your prose down with needless interruptions. They would be better edited down to a short quote if not removed altogether.

Let your own voice come through. Develop your own ideas. Don’t lean so heavily on your sources, but offer your readers something new, something of your own.

These are the conventions most of us learn as writers, whether through direct instruction or the editorial process. Blockquotes come to appear a sign of a developing writer, someone who’s not yet confident in their own voice, or an enthusiast, someone who can’t quite master their material. Mature writers, writers who have their readers in mind, will inevitably whittle these things down.

It’s worth noting, though, that this stylistic guidance—like all such advice—is highly time-bound and contingent. It is a product of a certain media ecology and a certain set of assumptions about writers and readers. It is a product of a particular set of aesthetic preferences, shaped especially by writers like E.B. White, Raymond Carver, George Orwell, and Ernest Hemingway. It was not, nor it need not, ever be thus.

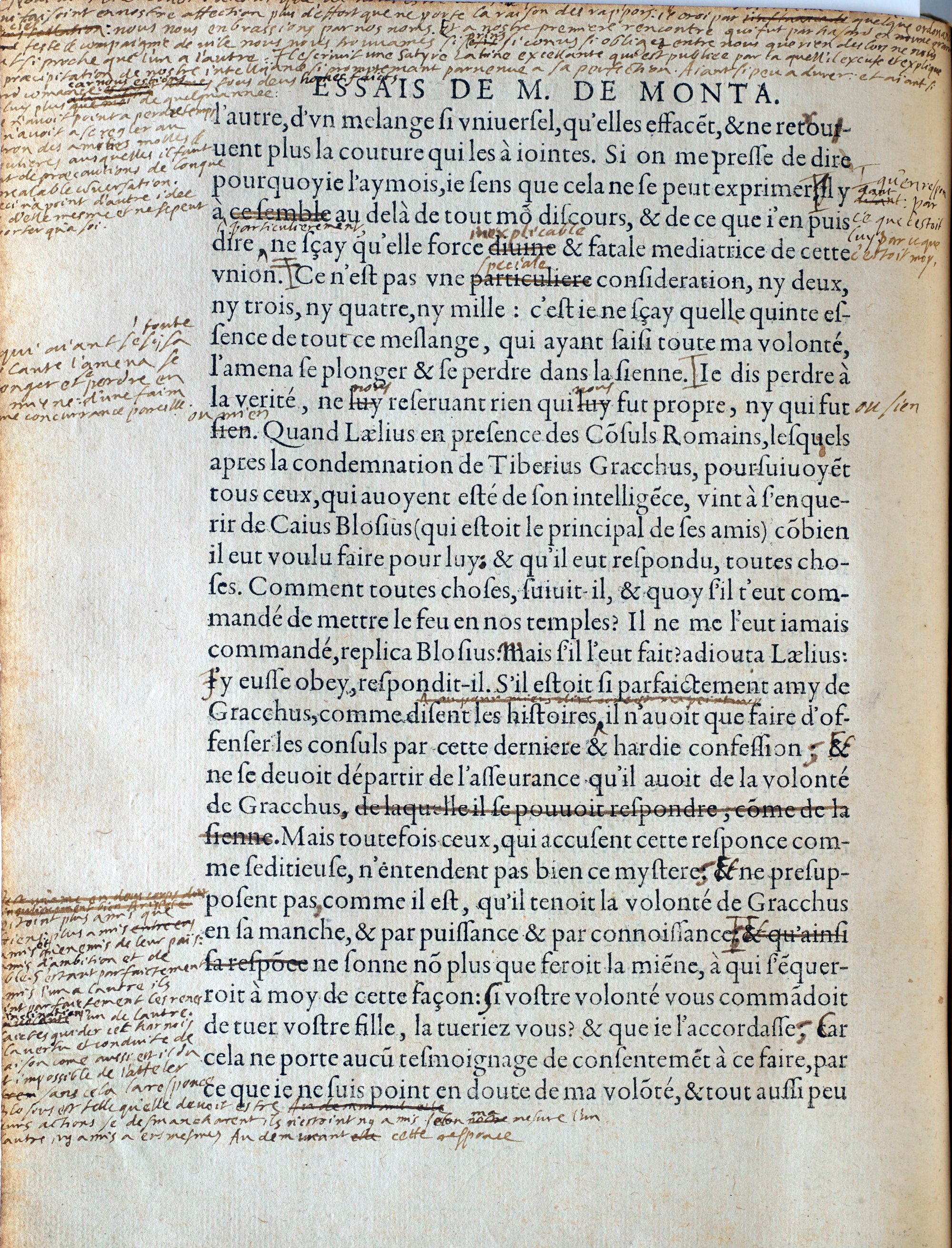

I want to offer at least a qualified defense of the blockquote. Yes, they are often tiresome; yes, I sometimes skip them too. In the hands of an unskilled writer, they flop around in the text like a fish looking for its way back to water. However, this year I have been slowly working my way through the essays of Michel de Montaigne. I figured that as a practitioner of the essay, I needed more than a passing familiarity with its creator. And Montaigne is delightful: deeply learned but also funny, subtle but also outrageous, perceptive but blunt.

And Montaigne, like many writers before the twentieth century, employs blockquotes prolifically. (At least, they are formatted as blockquotes in the Donal Frame translation I am reading. They may well not be in Montaigne’s original manuscript. But I am talking about the reader’s experience, so let’s not be pedantic.) At times, every point seems to need reinforcement from some classical authority or work of French poetry. Essays like “Of idleness,” “That to philosophize is to learn to die,” or “On some verses of Virgil” can seem like nothing but a tissue of quotations.

Yet the writer who famously claims “I am myself the matter of my book” can hardly be accused of lacking assurance; a charge of a lack of technical mastery won’t stick on the writer who invented the essay itself. And in my estimation as a reader, Montaigne’s blockquotes work: they add to the delight of the essays rather than dragging them down.

I have no doubt that I often happen to speak of things that are better treated by the masters of the craft, and more truthfully. This is purely the essay of my natural faculties, and not at all of the acquired ones; and whoever shall catch me in ignorance will do nothing against me, for I should hardly be answerable for my ideas to others, I who am not answerable for them myself, or satisfied with them. Whoever is in search of knowledge, let him fish for it where it dwells; there is nothing I profess less. These are my fancies, by which I try to give knowledge not of things, but of myself. The things will perhaps be known to me some day, or have been once, according as fortune may have brought me to the places where they were made clear. But I no longer remember them. And if I am a man of some reading, I am a man of no retentiveness.

Thus I guarantee no certainty, unless it be to make known to what point, at this moment, extends the knowledge that I have of myself. Let attention be paid not to the matter, but to the shape I give it. - Michel de Montaigne

I think Montaigne’s blockquotes work for two primary reasons. First is Montaigne’s lively mind. His stylistic decisions were not shaped, as ours are, by years of training in writing school essays or academic prose. Accordingly, he does not include quotes just pro forma—they don’t come into his text to prove his credentials or satisfy gatekeepers. Rather, they are vital conversation partners for him. When we read Montaigne, we see him in active and often passionate conversation with Plato, Varro, Horace, Virgil, and others. Because his quotes represent true conversation partners rather than signs of scholarly deference, they are vital and energizing rather than tedious.

[My book] speaks in many voices. - William Least Heat-Moon

Secondly, Montaigne’s quotes work because they represent a constitutive part of his formal innovation. Fiction and poetry are forms that depend especially upon the faculty of imagination, of discovery. But the essay, bound as it is to the non-fictional world, is primarily an art of arrangement. As John McPhee says, the nonfiction writer functions like a cook—you can only use what you have in the pantry and the fridge. Montaigne’s blockquotes signal this quality of assembly, bricolage, repurposing in the essay. Writers of fiction and poetry must wear their influence subtly, alluding to prior works in linguistic echoes or common narrative beats. Essayists have the privilege and the obligation to show their work more directly.

The world exists, not for what it means but for what it is. - Robert Farrar Capon

Great essays combine many voices, collage together various pieces of reality. They give shape to scattered fragments or disparate pieces of text. They exist not just to advance a thesis, but to give a form to things. Rather than the monologic voice of the author, they are works of dialogue. Blockquotes are a venerable tool in performing this work. We should not dismiss them altogether.