I'm in love with my friends

Exploring how Beatles songs reflect John and Paul's complex emotional bond and my own musical connections.

I’m reading a new book at the moment called John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs. It’s about the two famous songwriters and how the music of the Beatles defined their relationship.

The popular conception is that John Lennon was the troubled genius whose spiky wit gave the Beatles their edge, and Paul McCartney was the people-pleasing cheeky chappie, writing mainstream-friendly hits and propping up the band during the final years of Lennon’s descent into heroin and avant-garde. This book aims to dispel some of these stereotypes, and uses the songs of the Beatles as hooks to dig into the relationship between John and Paul and how it informed their lives.

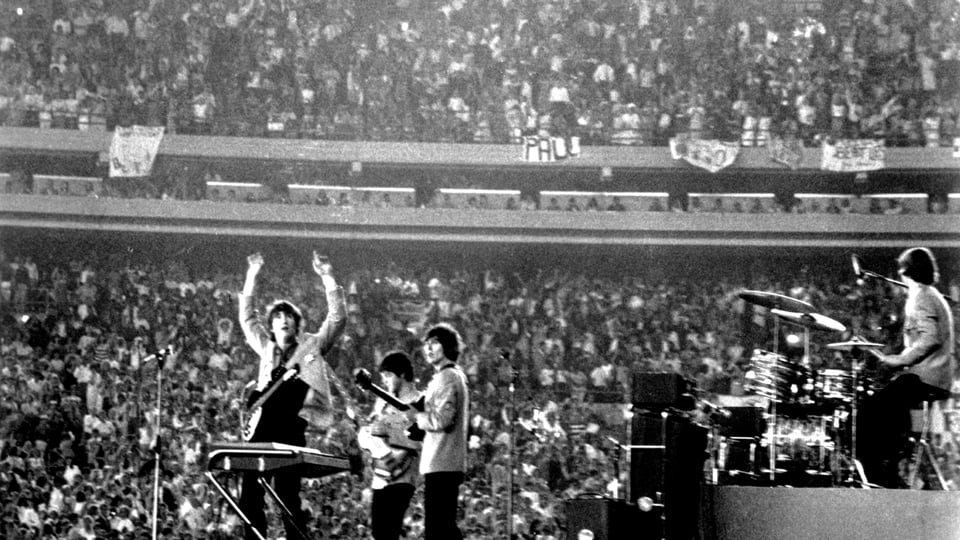

As both a huge Beatles fan and also an amateur songwriter who’s played music with lots of other beardy men who wish they were Lennon/McCartney, the premise of this book alone is right up my street. Watching the footage from the Get Back documentary, showing a month in the life of the Beatles as they try to coax another album out of their increasingly-unwilling selves, I was struck by the same observation that Ian Leslie makes with his book: John and Paul really do communicate through music.

There’s so much tension in the documentary: when all four Beatles are in the room and not playing music, the palpable sense of discomfort and things-unsaid is almost tangible. The years of drama, the egos and offences, and the sheer scale of what they’ve done up until this point is daunting: how could they not be warped and broken by it?

John and Paul in particular crackle with a kind of nervous energy: we’re watching it knowing how the story ends, and reading the signs of the fracturing relationship as they play out. But suddenly, Paul will sit at a piano and pick out the chords of a John song—Strawberry Fields Forever—and it’s like he’s opened a direct connection to John’s emotional cortex. You can see Lennon across the room, busying himself on his guitar while his musical partner pays tribute to him by playing his song back to him, soothing the row they were previously on the edge of.

I wrote here a couple of weeks ago about my mostly-failed efforts to persuade my male friends to watch Adolescence and share their thoughts on it. But during the same time period, my best male friends (and former bandmates) and I were exchanging snippets of ourselves covering love songs on WhatsApp group chats. Nobody specifically initiated it, we’ve got decades of history of this kind of open sharing of music. But I realised later that this was actually our “love language”, our way of expressing feelings without having to actually say them. We all have complicated lives and pressures of work, family, etc. But someone can just send a quick voice note of them singing to some guitar chords, and the rest of us jump to praise their voice, the delivery, or to share a snippet of something else they’re working on.

In our own small way, it’s the same thing I saw pass between John and Paul on that celluloid footage from 56 years ago: a language all their own in a world where sometimes it’s easier to express the deepest things in a shared tongue that transcends just plain ol’ words. I don’t think you have to be a member of the world’s biggest band in order to experience that – or indeed a man. But the whole reason I started this newsletter was in response to a legitimate criticism that groups of men don’t talk about their feelings when they’re together. Maybe we do, it turns out, we just do it indirectly.

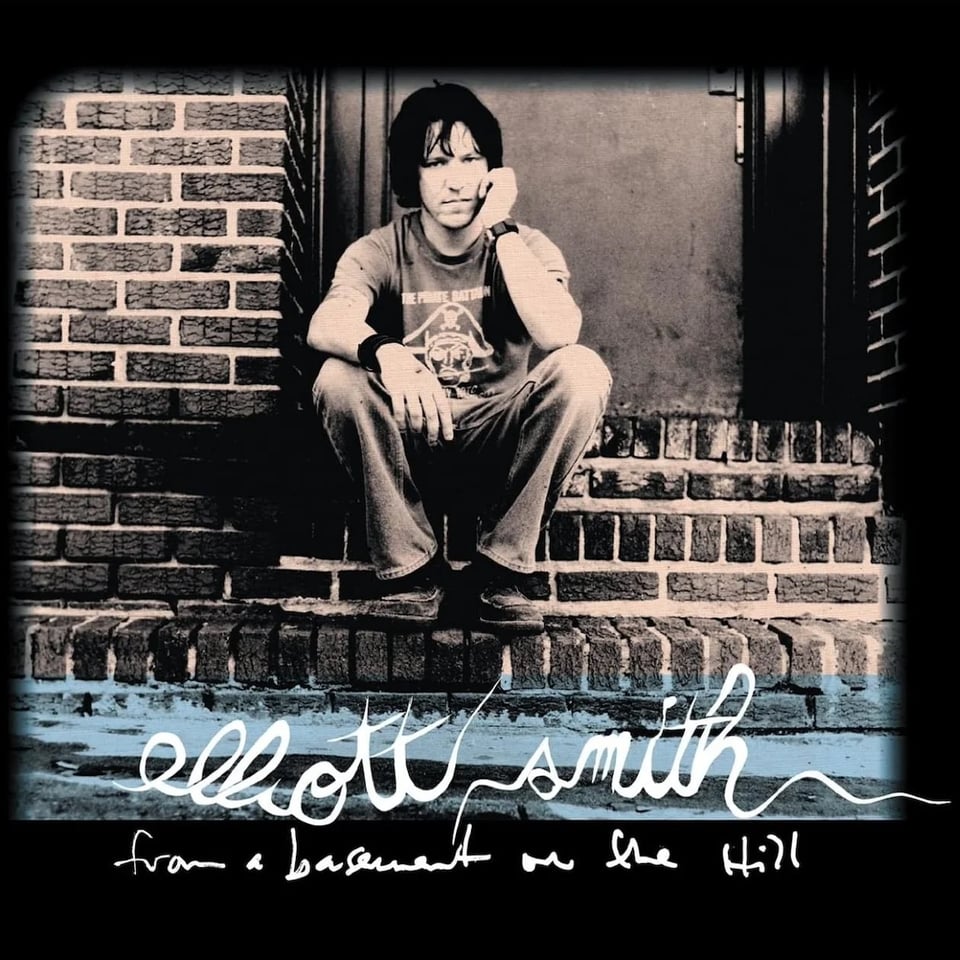

Years ago, when I was home for the summer from university, my parents had separated and were living in different homes for the first time. I came back and stayed with my dad in his otherwise-empty house, so he wouldn’t be alone. It wasn’t a fun time and I couldn’t wait to leave and return to my life of independence and adulthood back in Leeds. While I was there, I busied myself by learning covers of songs I liked – including Twilight by Elliott Smith. I didn’t have a printer so I found the lyrics online and wrote them out on paper so I could sing it. I left the sheet in my room.

My dad came home one evening and said “I found your song, in your room” and it turned out he thought I’d written it myself. I was briefly honoured that he’d mistaken my teenage scribbling for the work of a hero like Elliott, but soon I was horrified to think about him reading those lyrics and attributing them to me. He might even have thought I’d deliberately left them lying around so he’d read them:

Haven't laughed this hard in a long time

I better stop now before I start crying

Go off to sleep in the sunshine

I don't want to see the day when it's dying

Looking back on this now nearly two decades later, maybe some subconscious part of me was hoping that he’d find this stuff and understand how unhappy and lost I was feeling, even though I didn’t really understand it myself at the time. My dad, like most men of his age and generation, isn’t a natural when it comes to volunteering discussion about his emotions and feelings. But he too loves music, and will always get up and sing and perform songs of love, loss and reflection with his guitar and powerful voice – words he’d never otherwise be sharing without a song.

So perhaps there was something at work there that neither of us understood: but music runs powerfully through people, and gives voice to things we ourselves may not be able to say. I’m thankful for books like Ian Leslie’s for bringing it to light in the example of the most famous songwriting duo on the planet, so we can see the echoes of it in ourselves today.

Mini-feels this week

I’m in the money?

My new job comes with company shares, for the first time in my career. Being an absolute beginner in the complex world of stock markets and trading, I’m basically just ignoring them and not thinking about anything to do with investment or planning. Maybe some actual money will turn up in my bank account at some point? Who knows.

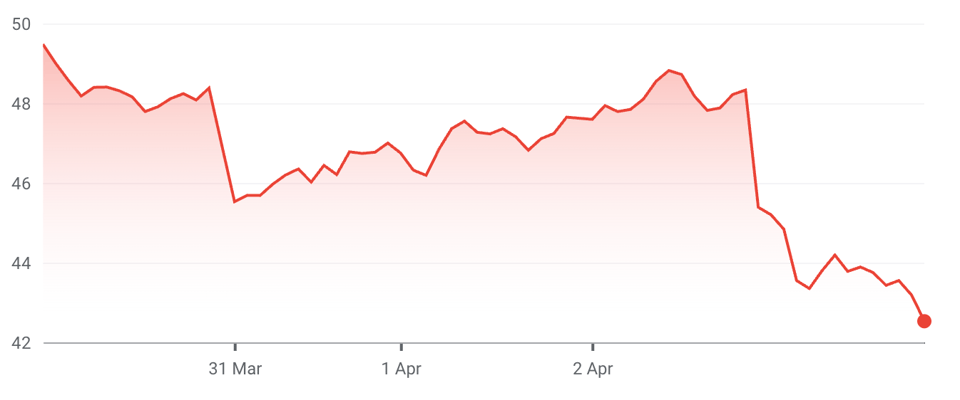

But it’s been galling today to watch the theoretical value of these things drop off a cliff thanks to the chaotic idiocy of Donald Trump:

Since we’re talking about man feelings: well, it’s enraging and depressing to see the actions of men who have never known true risk (or consequence) in their lives taking gambles that are only possible because of their ignorance of, well, everything – and never having to pay the price. I’m very lucky to have these shares and even if they fell to $0, I’d be fine. But the reverberations of the idiocy and arrogance we’re seeing today will echo around the world and I’m incredibly frustrated about that.