Where We Go When We Go

The middle of the year snuck up on me in a way that I didn't expect. That's on me. One moment, it was March and I was just beginning to warm up after a somewhat quiet and introspective winter season. The next, it's May and I'm getting ready for my birthday, a time I usually feel pretty weird about for a variety of boring reasons I'm sure my psychiatrist is tired of.

Then I look up and it's June. I spend the first two weeks of the month rotting on the couch from a vague illness that is apparently neither Covid or the flu but an extremely annoying third thing. It's pretty safe to say that I didn't get to send my newsletter out at a reasonable time. If it were up to me you would have read this weeks ago, but my immune system decided to stop showing up to work for two weeks so here we are.

Sucks to suck, I guess.

So, it's July. Thanks for opening up your email and reading this small essay I've created for you. Or maybe you saw it on social media and clicked through. That's cool, too. Seeing as I'm a month late and my tummy still hurts, let's try to make the most of it. By which I mean, I'm here to talk about death.

Maybe that's too on the nose. Grief is probably a better way to think of it. Loss. The abstraction of loss. The projection of that projection, the image held dearly behind your eyes, placed onto someone else, something else, somewhere else that is not here. Is not you. Is not me.

That kind of grief is something that I've been thinking about a lot lately.

Mr. Samuel's Teatime Stories for Good Kids and Confused Adults, like remembering the face of my long departed grandmother, evokes these kinds of feelings in me. It is a four-part video series created by multi-disciplinary artist Yara Asmar, a Lebanese musician, filmmaker, and puppeteer. She creates pleasantly melancholy soundscapes through distant, breathy vocals and tinny instrumentation, like listening to someone singing through the walls of a submarine. It's ethereal and lonely in a way that feels nostalgic for a time that I can't quite put my finger on.

If you encounter this project in the wild, such as a Reddit post or a YouTube explainer video, you may be led to believe that Mr. Samuel's is another creepy internet series. It looks like it could be a puzzle box mystery of some kind, or another cynical subversion of a children's show. That's the kind of thing we see all the time, from the creepypastas of old to contemporary analog horror projects detailing a show made for children that is secretly full of very adult creepy business that surely no child’s tiny explodable brain could handle.

You may be expecting a gloomier, overtly weird version of Don't Hug Me I'm Scared, which was not the first in this vein of children's puppet shows gone wrong but certainly one of the most successful and nuanced projects, spinning out of a series of online short films into a season of television. I know I was expecting as much when I first happened upon it through YouTube recommendations and curators in the space. Something like Mr. Roger's Neighborhood by way of The Caretaker's Everywhere at the End of Time.

But Mr. Samuel's is a small, beautiful, and heartbreaking thing. This rings especially true to me now as I sit writing this only a few hours after Yara Asmar posted the news that Dr. Michael Dennison has passed away. A poet and professor, Dennison played the titular Mr. Samuel across the four parts, a character Asmar has said is based on Dennison as her mentor and dear friend. There is a tender sort of naturalism to Dennison's performance that moves it beyond the context of friends working together on a project to feel embodied with its own stillness, it owns sadness.

The profound depth of that loss, no matter how distant or abstract through pixels and screens, feels very real to me at this moment. I've felt a strong tug of melancholy lately, more than just the disappointment of blown newsletter deadlines or the malaise of a prolonged and annoying illness. It made me want to write about Mr. Samuel after returning to the film once more already. The initial impulse inspired me to put pen to paper, but in light of this very recent news at time of writing, I think I should follow the instinct rather than shy away from it.

After all, Mr. Samuel is very much a story about death, insofar that everything is a story about death.

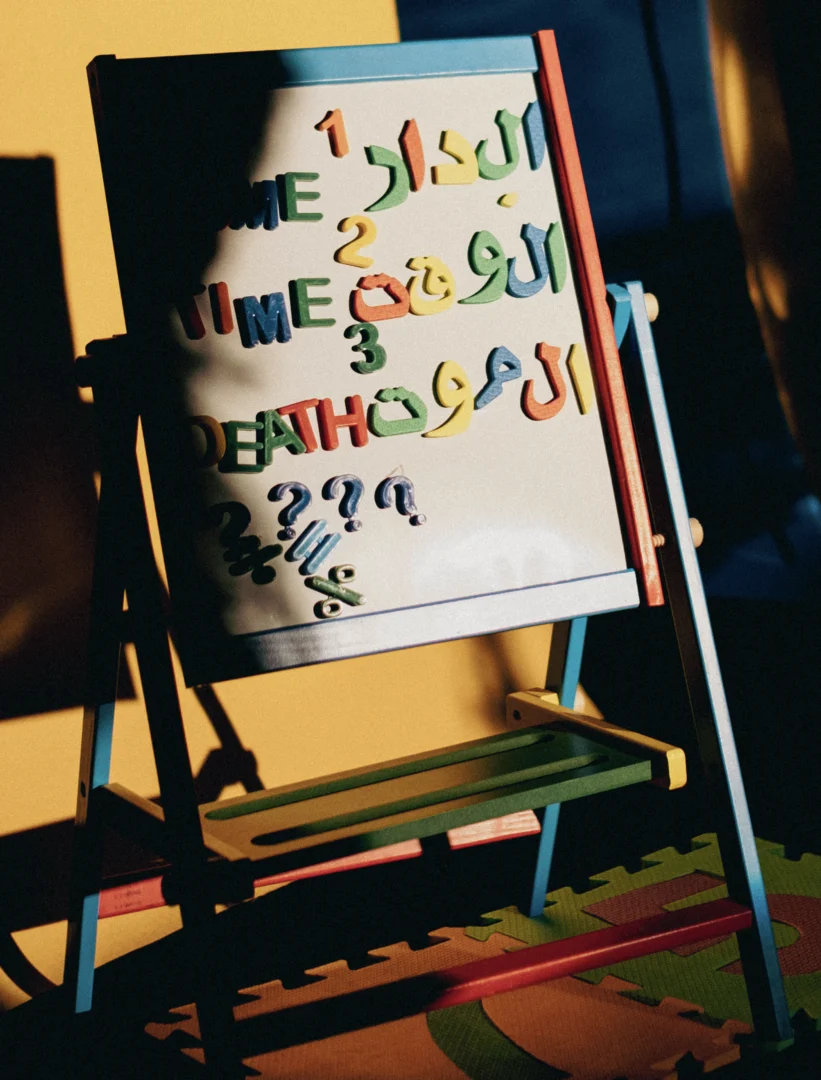

Mr. Samuel's Teatime Stories for Good Kids and Confused Adults is a show you can never forget. It is a place where time and memory collapse into strange shapes. A hypnotic, melodic, contradictory little trip into an abandoned children's show that has begun to corrode and break down. The set's initial cheery colors and playful sloping angles become harder to interpret as the wall panels move apart.

Over time, the set pieces recede into a foreboding nothingness as a gulf opens in the floor to draw the room inside it. The sometimes anxious, sometimes angry puppets talk and sing in disorienting circles on topics such as the shape of time and the ominous quality of sunlight. They are all quite ugly, from the bulbous head of anthropomorphic clock Gloomy Madeleine (played as Asmar) to the beady little eyes and unreadable face of The Sun.

Always seated on his wooden chair, Mr. Samuel is a weathered old man in a neutral-toned suit and scalloped black bowtie. His gentle demeanor and lively eyes seem a strange fit for his long stringy white hair, rumpled clothes, scuffed shoes, and the bat-like shape of his tie. There is a bright mind behind those eyes, but the light has grown dim.

Though well-meaning, he loses track of where he is and what's happening in conversations. The clocks are silly and he must shout at them to get them to tell the right time. His companion clock in Gloomy Madeleine doesn't keep time the way she's supposed to. Her bristling nature butts against his soft but repeated accusations that she is doing something to time.

The consummate host, Mr. Samuel tries to steer his show to its purpose of educating children. He teaches friendly lessons on dealing with life’s struggles to the audience on the other side of the screen. However, his simplistic advice fails to address the heightened, very adult anxiety underlying their questions. The storytime segments are either cut out or morose and absurd. With Mr. Samuel in slow decline, the puppets agonize over time, death, and the repetition of meaningless chores. Nothing ever feels resolved. Scenes dissolve into bickering or confusion with characters repeating their concerns or questions until the episode ends.

As Mr. Samuel, the man, degrades, so too does the set around him. The wall panels that define the space drift and dwindle, changing the mood of the room. A gaping void appears on the floor. It sucks everything into it in spirals of letters and numbers. The puppets seem to grow more confused and fretful, struggling to understand the increasingly morose lessons. Mr. Samuel tries to fulfill his role as the patient adult teacher, but he drifts away during the dreamy musical interludes about time as labyrinths, funerals as parties, and being untethered from the concept of home.

In the final part, there is only Mr. Samuel, his chair, and a window in the void. He speaks directly to the audience and stares into the -- your, mine, our -- screen. There is no outside to go to, and yet he wants to go. Only The Sun remains to ask, “Who do you talk to when we're not around?”

Mr. Samuel responds, “Where do you go when you go?”

The Sun assures him that there is no outside, there is only home.

Finally, Mr. Samuel closes his eyes, severing his connection to the audience. Whether in the respite of sleep or death, he is swallowed by the void.

But you still remember, don't you?

You're here, and you're watching. Even at the end of all things. You didn't forget.

There are some intuitive ways to read the series, I think, especially when taking the repetition of concepts like prisons and hell into account. Madeleine describes time as a labyrinth, cells upon cells endlessly arranged to create a deepening maze. Home is hell, too, according to her song. Home is all Mr. Samuel has, The Sun sings. It isn't much but it's theirs and they mustn't leave. Mr. Samuel welcomes the viewer home in each episode, yet home remains a place without comfort or rest.

The description of the series on Yara Asmar’s website further explores this theme of the prison, or an otherwise inhospitable space made from comforting shapes and ideas:

Zizek’s book ‘The Parallax View’ begins with a description of the first use of modern art as a method of psychotechnic torture: French anarchist Laurencic’s ‘colored cells’. “The cells were as inspired by ideas of geometric abstraction and surrealism as they were by avant-garde art theories on the psychological properties of colors… the walls, which were curved and covered with mind-altering patterns of cubes, squares, straight lines, and spirals which utilized tricks of color, perspective, and scale to cause mental confusion and distress.”

With an emphasis on set-building, the disintegrating world of Mr. Samuel manifests as a colored cell through a set that is falling apart, eventually leaving the protagonist floating alone in a vast void.

Following that logic, it's easy to read the series as a children's TV puppet show host trapped within a mental or spiritual prison. Perhaps he has dementia, or Alzheimer’s, and his memory of the set is distorted by his condition. The occasional sounds of creaking doors and movement around the set make me think of him in his lonely bedroom or sitting room, papering the old set over his surroundings. Perhaps he is dead or dying and these are simply his final moments, the desperate firing of synapses within an oxygen-starved brain. Perhaps he's the ghost haunting the set, unable to pass on.

Perhaps, most cynically of all, you, me, we are trapping Mr. Samuel there. This is what happens when nostalgia makes our eyes hungry and cruel. Perhaps we, the confused adults of his audience, are watching these episodes on some cracked thrift store VHS tape. Worse yet, we may be watching a Blu-ray release or Netflix restoration. Perhaps, by watching Mr. Samuel, seeking his guidance, the warmth of his presence, we are drawing him to this decayed set. We trap him in this limbo state, like an invocation of the dead. Our gaze is the void and we have stolen his light.

Denied him his rest.

His peace.

Perhaps in closing his eyes, obscuring his comforting gaze, he takes that peace back from us, in some way leaving the prison we’ve designed.

I don't think any of these readings quite fit right. They all feel true in different moments and bits of muddled conversation, especially when a puppet is singing that home is nowhere and everything is hell. Upon first viewing, I found myself pointing to these sung or spoken tidbits as declarative statements about the message of the work. But then I think again about the nature of the prison and I struggle with how that makes me feel.

The set, the show, is a contained space within the encroaching void. It is a place that we return to and seemingly can't escape. My instinct is to say that Mr. Samuel is not a literal representation of a person, nor is this set a real location. Instead, I think of the show itself as a container for the kinds of feelings we experience but can't put words to, won't express to others. Watching the puppets struggle to understand their circumstances through repeating days and chores, watching the set dissolve, gives space to sit with my discomfort in that watching.

But, at least in my watching, the true discomfort comes in how each episode offers a glimpse of a real, honest feeling or experience in my own life. The loss of a loved one you’ve cared for. The confusion or anger of a loved one who can no longer recognize you. The abyssal sensation that follows a death or personal crisis. The fear of change. The fear of stagnation. Of time moving on without you. Of death. Of dying. Of living on after someone else has died. Of living when you have no purpose. Of being in a home that no longer fits you. Of outgrowing that home. Of never leaving that home. Of having no other home to go to. Of losing someone. Of having nothing at all to lose.

Of being a scared, confused, and helpless adult in a world of horrors you were never taught to face, because the adults who came before you didn't, or couldn't, see them coming.

And, I think, underneath all of those anxieties, is the desire for comfort and familiarity. With it, the anxiety over that primal need to see a warm, kind face. To seek advice and to let someone tell you what to do. To make it better for you. It's a natural response to fear and pain, but can carry with it a sense of shame. The need for help in such a child-like way can sometimes feel like a further loss of agency when you already have so little. Such vulnerability is uncomfortable on its own, yet runs in stark contradiction to the warm feelings I still experience when watching Mr. Samuel.

The soft, distant melodies and dreamy vocals of Asmar’s score put me in a deep sense of ease. The puppets, while less friendly than what we expect puppets to be, are oddly pleasant to look at in their felt bodies and opaque expressions. Their performances sway between absurdly funny and bleakly mournful in ways that evoke empathy rather than fear. (Okay, well, Gloomy Madeleine is really off-putting, but Asmar’s performance endears her to me. She's giving Angela Orosco from Silent Hill 2 and I respond strongly to that vibe.)

More than anything, I find Mr. Samuel to be a kind, soft-spoken presence. Through his muttering and confusion, he strives to comfort the audience even as he floats further away. He makes me think of my grandmother at the beginning of my life and the end of hers. She used to take care of me as a child. As an adult, I took care of her in the years before her death when she couldn't sit up, walk, or feed herself. She could barely speak, eyes wandering around the room as she mumbled garbled words and chuckled at jokes no one understood. There is a grief in that reversal, the process of watching someone whose presence alone comforted me succumb to the fog of memory loss, brain damage, and physical decay.

Ultimately, this is what Mr. Samuel's Teatime Stories for Good Kids and Confused Adults means to me. This is what I find it to be about. It is less a discrete story of prisons and more a space to freely express and experience grief in all its forms. Confusing and warm, welcoming and cold, anxiety-inducing and comforting, the inherent contradictions of the show and the scared characters who inhabit it compel me to keep watching.

To remember.

To grieve and let go.

All photos courtesy of YaraAsmar.com.

Add a comment: