We Wander the Newmaker Plane

If you were the kind of child who spent many hours unattended on your family's home computer in the 1990s, you, like me, probably have vague memories of clicking around empty screens. You may have had games installed on the system to keep you distracted, like Barbie or Pajama Sam or a generic math puzzle game. You may have had strict rules in place to keep you off websites and out of internet chat rooms. Maybe these rules kept you safe.

But you may have been left to your own devices. Perhaps you did go to those chat rooms and had uncomfortable conversations with people who claimed to be other children. I know I did. You may have wandered around the hard drive's contents, looking for Solitaire or Minesweeper with their chunky pixels and cold, static windows.

You may have clicked through programs like Word or Paint or Excel to see what they did and how they worked. You may have looked up forums for weird stuff you could do on the computer if you mashed certain keys together or opened certain system prompts. These were basically just digital ghost stories, rumors about hidden games and secrets inside the machine, but you had free time and nobody was watching you.

You wait until your mother isn't looking, which is easy because she's rarely minding you. Seated in the big, cheap black office chair, your feet barely touch the ground as you wheel yourself toward the desk. You take a deep breath and read off the steps you carefully wrote down on a sheet of scrap paper. You murmur so no one can hear you conjure these things on the screen.

It's scary. You feel like you're doing something wrong, or that you’ll break this very expensive toy your father is currently obsessed with.

For better and worse, the secrets you find aren't particularly scary. You find the archaic pinball game in Word, the glitchy, goofy flight simulator hidden in Excel. Both crash. You feel a bit at odds with your discoveries.

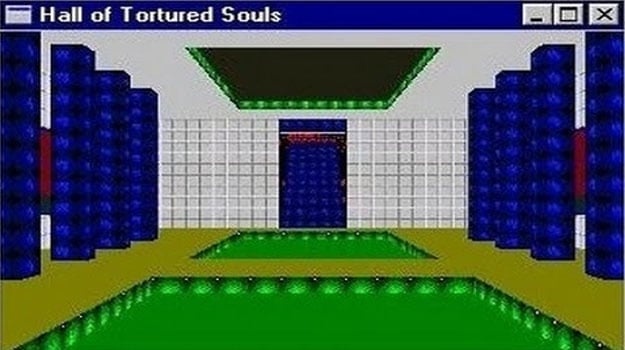

But forums and websites mention an older version of Excel and something called The Hall of Tortured Souls. It's a hidden level inside the program. Just the name makes your stomach hurt.

Then you see the images.

You've played scary games. Of course you have. Your parents let you on the computer alone. You play Doom and Wolfenstein 3D. You've seen blocky men explode in pink splashes of meat and blood. You know these images aren't scary, but you can't help but feel afraid.

What are these rooms, these shapes? The garish colors read like the stripes of a poisonous snake. Stark angles meet to create inhospitable spaces that defy a child’s understanding of the world. You can't see what's lurking behind the pillars or at the end of the zigzagging walkway. A person? A creature? Something worse?

It turns out that the grand corridor and stressful walkway leads to a chamber with the names and faces of the developers. They are the tortured souls trapped in the hall, smiling in pixelated team photos. It's just a joke left behind for users to stumble upon. But this is the first time that you realize that someone can put something in a program that doesn't have a use.

Something can just exist inside the computer. A little pinball game or flight simulator is a silly thing to find. A hidden room made from upsetting geometry? It serves no function. The hall isn't made to be used or played the way you understand a computer program to be used or played. It exists to unnerve you.

So how do you ever trust what you see on the computer again? If people can just make whatever they want inside the computer, how can you ever trust them not to hurt you?

When I tell you that I like horror, a handful of images probably leap to mind. They're dependent on your tastes and experiences, I’m sure, but you can see them. A slasher killer or creature feature. Demonic possessions or cursed dolls. You thought of a scary movie, a splatter novel, or the cheap, earnestly goofy haunted house attraction you attend every Halloween. We all share common visions of what something scary should look like. It's a primal sort of vocabulary, extending back into the darkness of evolutionary history, where our ancestors learned how to fear and why.

Then I say I like internet horror -- things spawned in the depths of Reddit or coughed up by YouTube -- and I can feel the air in the room change. No, I assure you. It's actually very interesting and has real artistic merit. I can prove it. No, I won't tell you about The Backrooms again, I promise.

Try as I might to consider these kinds of projects with the compassionate eye and academic rigor I bring to everything I engage with, there is a kind of…funk to it all. You know? For every Candle Cove, Local 58, Sirenhead, Molly Moon, and Kane Pixels to escape containment as art or artists broadly worth discussing, there are a hundred gross, boring things to slog through. Edgelord sensibilities, cheap tricks, and trend chasing make the online horror space a little tedious sometimes. It happens to everything in every corner of the internet, and there are hundreds of really interesting stories and projects out there to make that hunt worthwhile. Don't take me the wrong way. It's just the rampant unseriousness of both art and artist that sometimes wears on my nerves.

I want something to grab me and unsettle me. Make it hard to be alone in a room or awake in bed at night. Maybe I ask too much of internet horror, the domain of haunted video game cartridges and creepypastas. But I don't think that's true. I think I ask what I ask of any other artist. The internet is where people go to be lousy because the non-existent barrier to entry encourages novices and outsiders to try their hand. That doesn't mean there isn't good art and good artists. It just means I have to work harder to find them.

Lately, I've been falling asleep to the YouTube channel VibingLeaf. This is a compliment, not a slight. I only sleep to things that I really love. Once home alone for the day while my girlfriend is at her outside office job, I find random horror projects to watch while I work. Short films or alternate reality games. Five Nights at Freddy's fan game compilations or many hours’ long playlists of creepy animations. If I really need to relax before or after work, I put on long-winded analysis videos and let myself be carried away by clips from weird mixed media horror projects and the soothing narration of a Nick Nocturne or a NexPo.

But VibingLeaf feels different. For one, the channel is host to original short animations and films. The artist behind the account (known only to me through the username and short channel description) focuses primarily on video games as the site of horror. Think Sega rom hacks, cursed bootleg Pokémon games, and things living inside your gaming console or amid your computer files.

Some pieces are reimaginings of well-trodden internet scary stories and creepypastas about lost episodes of SpongeBob SquarePants or copies of Sonic gone wrong. Though these pieces build on the framework of familiar themes, stories, or characters, they are imbued with an unshakable dread. A dread that I find both comforting and disquieting in alternating measures.

I am a product of the internet as it was in the 2000s and 2010s. Before the world wide web metastasized into a clump of heavily surveilled, algorithmically-driven ad dispensers, it was a weird place. It was also a deeply creepy place. Curses sent via chainmail were in constant circulation. Horror stories, digital urban legends, and monsters birthed from forum threads ran wild.

These were the days of Slenderman. Ted the Caver. Jeff the Killer. Suicide Mouse. The SCP Foundation. Obey the Walrus. I Feel Fantastic. Blank Room Soup. Supercuts of obscure advertisements or performance art projects, taken out of context and circulated as cult propaganda or death footage.

While I did my time in the horror trenches of my youth, I always skewed to the nerdier side of the creepy internet spectrum. I enjoyed SCP entries and Slenderman found footage series as much as the next insomniac teenager, but I was obsessed with creepy games. Not horror games, per se, although it is my favorite gaming genre. Rather, I was fascinated by the broader landscape of horror fiction surrounding the games.

I love hacked versions of Super Mario World and Sonic the Hedgehog 2. I love mixed media ghost stories like Ben Drowned and Godzilla NES, which used edited screenshots and original assets to document hauntings. I love weird anomalies in first person shooters and characters appearing in empty online multiplayer maps when no one else is logged onto the server.

It's all so weird, crunchy, and…intimate? Comforting? Nostalgic? I think nostalgic feels like the right word. A warm kind of despair. That's the way ghosts make me feel, anyway. Not afraid, but…comforted and deeply saddened. It's a feeling that VibingLeaf perfectly captures in these short, bite-sized animations.

Usually framed as the video of a kid or young adult made for their gaming YouTube channel, the cheesy slideshow presentation feels lovingly authentic to the origins of this particular subgenre. The player character documents his experiences with games acquired through dubious means and the strange occurrences that happen during gameplay.

The sprites of these games are flattened into deteriorating shapes, cast into dark environments that feel as if they are melting into the static of a busted monitor. Corroded voices get lost amid the muffled, ambient drone. The spark of some presence, a kind of unknowable sentience, makes itself known through sprites and game characters who display self-awareness, grief, and -- most upsetting of all -- love.

Love is a recurring theme in VibingLeaf’s work, and it terrifies me. Because these are games with win and loss conditions, and because violence is the primary vehicle of progression or achievement, these characters are subject to great suffering at the hands of the player character. Yet even as they are unmade by pixelated violence, characters will deliver long, heartfelt messages to the player, telling him that he is forgiven and loved. They ask him to take care of himself using language that feels too intimate to be programmed but that is rarely remarked upon by the player.

Instead, he opts to add in a joke line about his computer getting hit with a virus from playing bootleg games. It's grimly funny, sure, but it's also profoundly sad. Something is trying to communicate with him, but he can't see beyond the narrow scope of gameplay.

I think that's why VibingLeaf’s work resonates so much with me. It plays with the idea that first occurred to me when I was just a kid, scaring myself over pictures of halls hidden inside spreadsheet programs. Within the fiction of these games, someone, something, made them for reasons other than play. They exist to communicate. Perhaps to facilitate some connection to the player, to the outside world. To seek freedom.

But freedom from what?

If a game isn't made to be played, then what is it made for?

I wouldn't consider myself a technophobe. I grew up with too much technology within reach to really be genuinely afraid of it. Beyond the familiarity fostered by the family's big, chunky desktop computer, I'm of the generation that first saw cellular phones in movies. Now everything I do is on a pocket-sized computer that I call my phone out of habit. I only use it to make calls when there isn't a form I can fill out or a message I can send instead. My car used to have manual cranks for rolling down the window. Today every button is attached to a sensor attached to the dashboard, and they all barely work.

I certainly have no love for technology. I don't fear it, per se, but I don't respect it. Rationally, I understand how various forms of technology make human life easier. If not easier, then at least less awful. I still think of myself as subject to technology the way I'm subject to the weather. All of this would be less overwhelming and scary if I had my druthers, but I don't, so I have to be plugged into the internet the same way I have to prepare for Florida's rainy season.

While technology as a specter, a concept in the ether, doesn't frighten me, video games do. I can't really think of anything scarier than a video game, if I'm being totally honest. As humans, our brains understand physical spaces as functional…things. Your house. The local grocery store. Your dentist's office. A parking garage outside a shopping center or sporting arena. These are spaces made out of shapes that are designed to house human bodies. Maybe not indefinitely, maybe not comfortably, but their mere existences are proof of their purpose and our continued need to make them. As long as there are living things, we will find a way to put a roof over four walls.

But a video game is weird. You know? It's just weird. A game game makes sense. You create rules and modes of engagement to achieve a determined goal and arrive at an ultimate win or loss state. It may not always be fun the way we conceive of games as fun, but I understand the emotional and social needs for chess or Settlers of Catan the way I understand the need to kick a ball around a field or throw it into a hoop. A game may involve role play or narrative progression of some kind, yet you never leave your material, physical plane of reality. A new reality is never put in front of you, asking you to suspend disbelief in order to engage with its mechanics, modes, and rules.

Let me put it another way. You go to the park to play pick-up basketball with your friends. You go to the YMCA to play indoor volleyball. You willingly enter and occupy structures that are made to be hospitable to human beings. With a video game, you're vulnerable. You're entering a digital simulation of reality, projecting yourself into a space created by other people without the precedent of shelter or care.

You can build an inhospitable house. It can have sharp angles or low ceilings to make it hard to navigate. But the house can't attack you. It still has a roof and four walls to keep out the rain or cold. In a game, you are surrendering yourself to something that does not have a purpose, and therefore an obligation, not to hurt you. After all, in games -- at least the kinds of games we usually tell scary stories about -- your avatar can die, whether by an obstacle in the environment or an attack by an opponent character. Death is something you strive to avoid because it is a real and present threat in these spaces.

You can't trust a person not to build spaces or systems to hurt you in a game. In fact, many games are predicated on these kinds of violence. It's an agreed upon violence, of course, because most games are commercial products that exist to be enjoyed and make money. You agree to get your ass beat in Dark Souls because you agreed to play Dark Souls in the first place. But the possibility still remains, like with the Hall of Tortured Souls, that someone can break that contract and create things within the game space that you didn't agree to.

I don't mean that in the sense of consumer expectation or entitlement. I don't really care if a game or other work fails to meet your arbitrary tastes. Rather, I think about this in terms of intent. A ghost inside a machine doesn't scare me because I am inclined to empathize with it as a tragic figure. Even a demon or evil spirit feels very simple and, as a result, not particularly scary.

But something designed by a person, a stranger, whose intentions I can't know? That's something else entirely.

I think I can say, with little to no hyperbole, that Petscop is one of my favorite things to ever exist. I also think that it was the most powerful exercise in digital horror of the 2010s, leaving a crater-sized impact on scary internet stuff that I still see and feel today.

Talking about Petscop is hard when you love it so much. That's why I've avoided doing so since it first crashed head first into my life back in 2017 and helped rewire how my brain thinks about telling stories.

Petscop is an online horror series created by Tony Domenico, told in twenty-four parts from March 2017 to September 2019. It is presented as a YouTube let's play made to document the player/protagonist Paul's experiences with a mysterious game. Petscop is an unfinished, unreleased PlayStation game produced by a company named Garalina and he has the only copy. It isn't clear how he came into possession of it, but it was in his home. The cover came with a note attached:

I WALKED DOWNSTAIRS AND WHEN I GOT TO THE BOTTOM, INSTEAD OF PROCEEDING, I TURNED THE RIGHT AND BECAME A SHADOW MONSTER MAN

6/13/97

For you:

Please go to my website on the sticker and also go to roneth's room and press start and press down down down down down right start

The game Petscop does not exist. It was fabricated by Domenico for the purposes of telling this story. Well, people have recreated the game since 2017, but for all intents and purposes, we're watching a fake person play a fake game.

Up front, Paul's narration is directed at a singular, unnamed person for whom the videos are made. He's doing all of this to prove that he isn't lying about this game or its contents. We come to know Paul’s name from the title on his save files. We come to understand he's probably in his early to mid twenties, a little spacey, a little meandering. He announces that his method of interrogating the game is based on logic and science, but speaks, makes observations, and cracks awkward jokes about what he sees in a way that reads as impressionable and easily swayed. Paul also has trouble telling the difference between “lefts and rights” and wants to use his friend’s “puzzle genius” to get through this strange game.

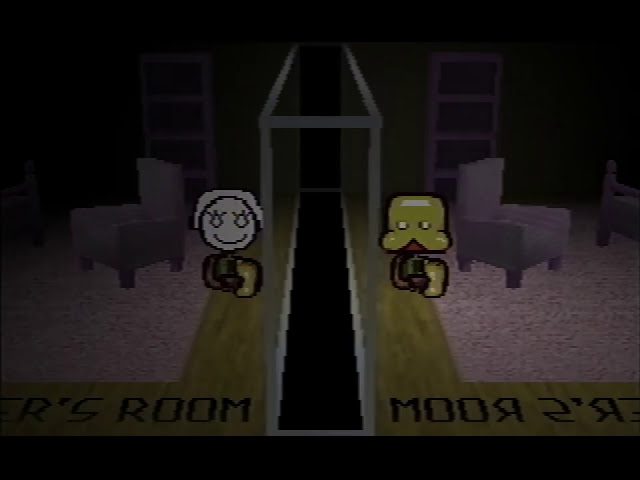

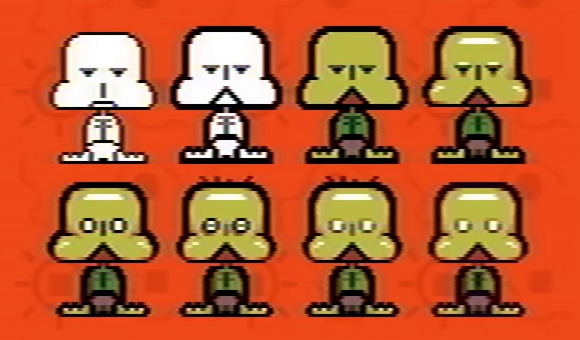

The character avatar that Paul assumes is a squat, grim, green little creature. It has a large head with milky eyes and few identifiable features. The feet are large and it has no arms or hands. Paul's avatar navigates a cute if empty and unpolished pastel level called the Gift Plane, a puke-green shape in an otherwise pink and white space. Here, he collects anxious creatures called “pets” who are left behind when their home, a facility called Even Care, is abandoned by the staff. Using the code found on the note, Paul unlocks a secret level beneath Even Care. This vast, dark nothing is called the Newmaker Plane.

Here, Paul finds crude buildings with faces on them, gravestones with the names of dead children, and the ominous Child Library which houses rooms that represent members of his own family. He meets Care, the distorted, crying child sprite who looks like Paul, is the same age as Paul, but whom Paul doesn't remember. At some point, she disappeared, taken from her home and kept in the basement of her school. Nobody will love her in this state, he reads in her character profile. Nobody will love her ever again. Despite this, Paul begins the process of catching Care like all the other pets above and depositing her in the Child Library. That's the objective of the game as presented, and Paul mindlessly follows instruction.

Wandering the Newmaker Plane is what exposes the true hell that is Petscop. There is no light here. The tight spotlight on Paul's avatar illuminates his path but keeps the claustrophobic corridors and empty rooms steeped in shadow. The game is silent but for the squishy slapping sound of the avatar’s footsteps and the off-key jingles that play whenever Paul collects “pieces,” the name for the in-game collectibles. The few characters you meet are strange and foreboding, and Paul is all but begged not to play. Doing so enacts some kind of vague harm on the characters within the game. He doesn't listen.

Paul's travels become all the more menacing as he stumbles upon recreations of his house, his school, and family events from his childhood. He moves deeper into the game by solving intricate puzzles that make less and less sense as he progresses. Messages from a disturbed individual named Rainer are scattered across empty suburban simulacra and allude to horrors lurking in Paul's family history. The nature of the videos, insofar as who is editing and uploading them, becomes increasingly unsettling once it appears that an entity or group has assumed control of the channel itself. What they choose to censor, and Paul’s disturbed reactions to those censored objects, remains unclear until the later episodes of the series.

Time and space collapses within Petscop. Paul finds members of his family, or memories of his family, or perhaps digital ghosts trapped by the game's interface, moving in loops through different stages of development. Their -- and his -- avatars hover at the edge of the screen or mirror each other's movements through rooms. Conversations he's had with family members are played back to him and items from his personal history appear as in-game objects, obscured by a black box to hide them from the growing audience. Everything revolves around Care, her disappearance, and what happened in her home. All the while, her father, Marvin, begins to appear more frequently, the shadow that looms over the game and Paul's deepening connection to Care.

In following the episodes, watching Paul piece together the fragments of his own life, we come to see Petscop for what it is. The game is a trap, made by Rainer, holding all the evidence he has against Marvin. It places every crime, every sin, into an opaque but playable narrative. Every member of Paul’s family is in it. Their player inputs were recorded, movements on the controller replaying over and over as Paul's character moves through the game. Paul was never meant to play Petscop, but he is in it. He is of it. Whatever Petscop is now in this abandoned state, it documents the abuse, neglect, and profound harm enacted upon and experienced by children.

Petscop, the series, is purposefully vague. Domenico has stated in interviews that there is a concrete, literal plot but that he took out everything that would illuminate too much. What we are left with is a game as a metaphor, an impossible one-man creation with AI that defies reason and captures hundreds of play sessions. The characters operate on a kind of dreamy intuition that escapes the viewer's immediate grasp, and the game itself is far too advanced to be made by an amateur developer, given the hardware limitations of the 1990s. It doesn't make logical sense or ground itself in reality.

A dedicated community of fans and a cottage industry of YouTube explainer videos emerged to nail down the definitive series of events presented in the series. That's all well and good, but I don't really care about deciphering its mysteries. Once the underlying story became clearer toward the end of the series, I found myself wanting this kind of resolution less and less. This isn't a slight against Domenico’s work by any means. It just isn't what sticks with me about Petscop in the intervening years.

For me, the real horror of Petscop doesn't lie in dead kids or family secrets. The game as presented is a hateful contraption. It began as a crude attempt at designing a catch-them-all game before it was broken down and reformed by the rage festering inside its creator. The game fails in its intended purpose as a weapon against Marvin and so it continues to live on within Paul's family, moving from member to member before it comes to Paul. Like the abuse it depicts, it lives alongside the family, something people know is there but don't talk about.

There are many broadly agreed-upon interpretations that argue Paul is only loosely connected to Care and the family, but I think Paul and Care are the same person. (It’s also my essay and I make the rules.) Care feels like the fracture point between potential realities. If you know, you know. There is the you before this happened to you and the you who is born in the wake of it. These versions of yourself move through different planes of existence simultaneously, but you feel the other you there. Through the wall, the floor, living. Breathing. I knew where my other self lived, what she wore, what she did every day. What she wanted to be when she grew up.

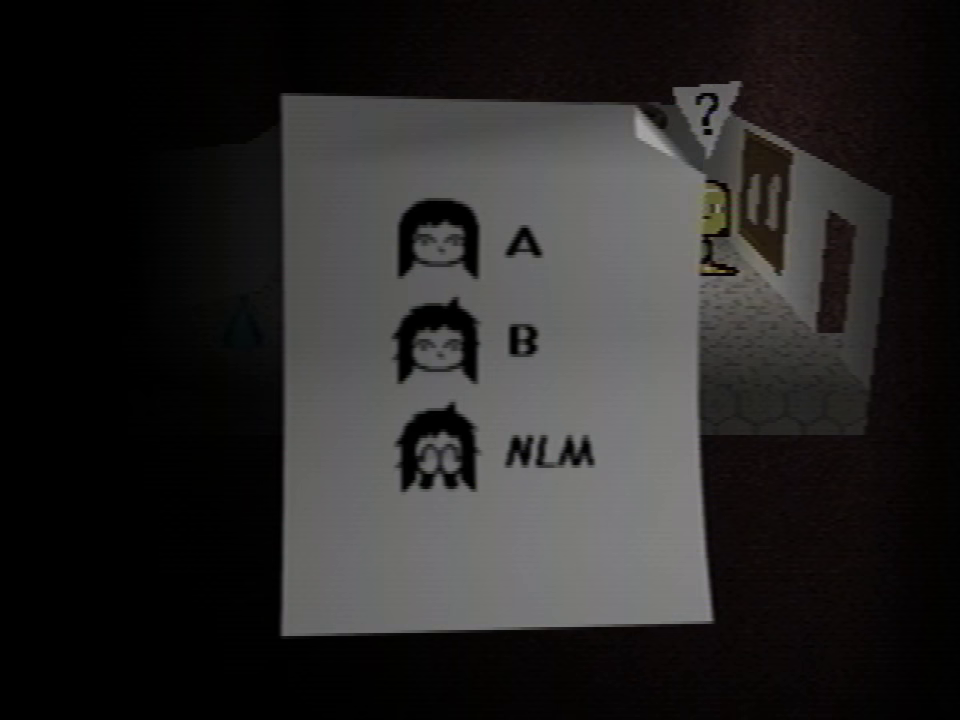

The experience is literalized in Petscop as the pleasant veneer of the Gift Plane and the rot of the Newmaker Plane beneath it. Paul can traverse the two levels of reality by becoming “the shadow monster man” as described by the note, taking the role of both the abuser and the abused. It also manifests in the states Care exists in as Paul catches the versions of her throughout the series: A (happy), B (hurt), and NLM (nobody loves me). Care is who Paul was in some capacity, the parts of him left behind, cast off for his own protection. She looks like him and has the same birthday but he doesn't remember seeing her at family gatherings. She is the ghost of a once and potential life, named for the very thing Paul was never provided.

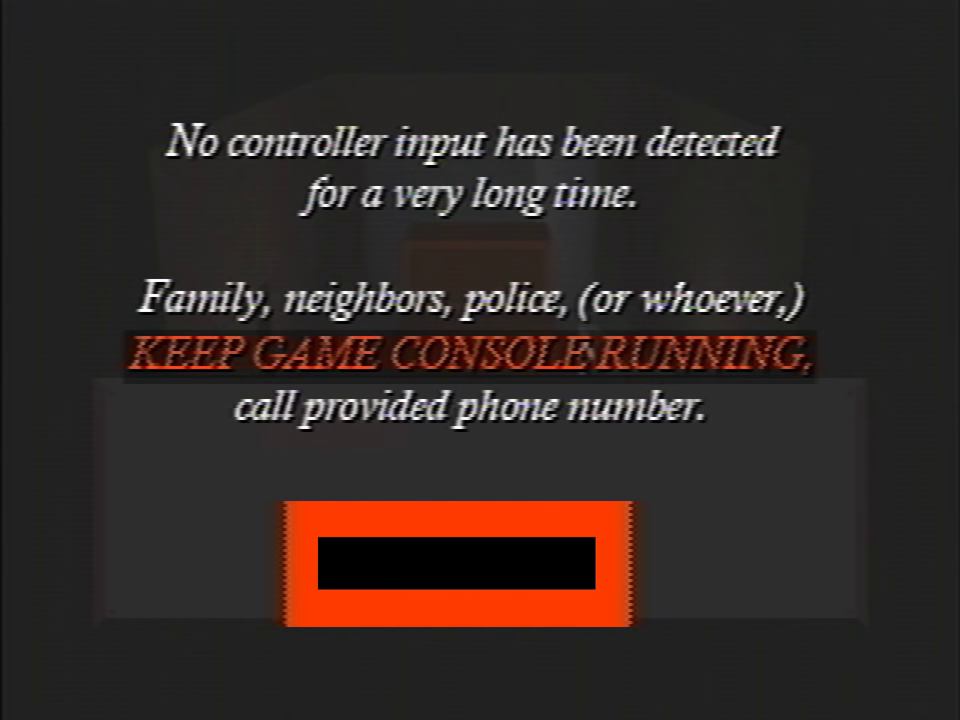

Through his experiences with the game, Paul rediscovers the extent of his own trauma, his own abuse and neglect. Or, more accurately, the viewer does. Paul physically leaves the story when he exits the room he's been playing in while the PlayStation runs in his absence. He never appears again. It's a stressful thing to leave unresolved, I will admit, even after all these years. The player character, an AI based on recordings of Paul’s play sessions, continues the game, putting the puzzle pieces together and unlocking the testing modes required to access everything buried within the game's files.

Paul's AI doppelganger achieves the closure, however cold it feels in the end, that comes from finishing the game and “beating” Marvin. It isn't so easy for Paul, who must now presumably live on with the grief of what he now knows about himself. Petscop is as much a fantasy as it is an indictment. Rainer, who we come to understand to most likely be Paul's cousin Daniel, is so broken by his rage at what Marvin has done that he makes a game where Marvin can be defeated. It's comforting, but empty.

The player AI character discovering the truth of Paul's family -- the one that raised him and the one he’s now chosen at the end of the series -- offers little solace. We, like Paul, have to live with this knowledge and its discomfort. Rainer, Daniel, seems to have disappeared or ended his own life after the completion of the game. Marvin never saw any real justice from what I understand of the series’ events. Paul's mother and aunts have lied to him about his own experiences, his own pain, until he can no longer run from what Care represents.

To me, Petscop the game is a simulation of the systems within families -- and American society as a whole -- that perpetuate abuse. Petscop the series is an unflinching exploration of those systems through the uncertain fog of childhood memory and dream logic, watching adults turn a blind eye to the horrors in their own homes at a distance that allows catharsis. It is harrowing to watch through that lens. I've been the small child no one protected from the cruelty of adults. I've watched my aunts and uncles wave away the actions of predators in the family because confronting them was too inconvenient. The metaphor of the game being on for seventeen and a half years and the footage being edited by a family eager to obscure its complicity feels painfully apt when you’ve lived it for yourself.

Using a game to represent the directions we receive from our parents and how they drive us to take part in actions to hurt ourselves and others on their behalf is brilliant. Games condition us the way families do. Rules taken for granted as natural law. Stark win and loss states that can feel like moral judgments. Rewards for meeting or exceeding expectations. Paul collecting children to win an increasingly morose and upsetting game based on the vaguest of incentives rings as true as being told you're mistaken about what your parents do to you and how it makes you feel. Because if you know, you know.

Although not a playable experience, Petscop captures everything that scares me about video games. It also excites me to revisit, a haunting example of digital horror that understands that the ambiguity of games is what truly makes them scary. The ambiguity of their designs, spaces, and intents, the truths hidden beneath their visible planes. If you're lucky, it's a wounded spirit trapped inside a machine. Otherwise, you're left alone to confront the banal violence that occurs in our homes.

That feels so much worse than anything a ghost can throw at me.

-

Just wanna say seeing this in my inbox made my day. Gonna wait to read it while giving blood, which seems suitable for the subject matter.

Add a comment: