We Happy Sisyphus

"Already at that time [2001], I began to think that if I didn't develop Evangelion as content, there would be no future for anime. If that's the case, I should do it while I can."

Hideaki Anno

And who by fire, who by water

The thing about Evangelion is…there's a lot of it. In terms of merchandise, licensed products, and related media, there is a truly absurd, and frequently perplexing, amount of stuff to go around. Landfills and landfills of it by now, I'm sure. As an American who came to the series in the early 2000s through forum posts, translated scripts, and pirated episodes, I still can't see it that way. It seems too surreal. The total glut of merchandise has yet to crash and wash up on my shore, separated by an ocean of time, space, currency, and language.

Of course, I know it's there. I have access to the internet. Such is the nature of corporate synergy, promotional tie-ins, and merchandising. A kind of franchising called "media mix," a shared world of stories, marketing campaigns, and products designed to maximize profit by turning characters into brands and mascots. Cartoon influencers, if you will. Japanese media has been doing it for a long time, though I feel like us in the Anglosphere got our first real taste of it with the interconnected, multiplatform, decades-spanning Marvel and Star Wars cinematic universes under Disney. This is a purely vibes-based analysis, so don't quote me.

I guess the same thing could be said of American children's toy and cartoon franchises historically, your Transformers and Rainbow Brites, GI Joes and Barbies. And boy, were the Barbie movie marketing campaigns this year an inescapable maze of publicity stunts and branded junk, from butt cream to frozen yogurt. There's just a tenor to the merchandising push now, I think, the shiny novelty of a universe of plastic and screens to plug yourself into that feels oppressive once the veneer has rubbed off.

Not to sound old, but I remember when promotional campaigns used to just include a Happy Meal toy, a character on a cereal box, and a cup from Burger King. I suppose being able to cover every square inch of your home in Iron Man or Kylo Ren just hits different these days, you know? At least, it does for me. I believe Sarah Hightower over on Twitter once said that Disney fans are just American otaku so we shouldn't throw stones, and, like. I can't really argue with that.

Evangelion being an established billion-dollar franchise, merchandise and promotional campaigns are often memed and joked about in my corner of the internet. Shinji, Rei, Asuka, and the rest have been used to promote everything from horse racing to waste management services. Bowling alleys and lingerie brands.

And yet the series and its characters still feel…singular to me. Precious.

No matter how much jewelry and clothes and figures and underwear and shampoo and trains and cars and razors and pachinko machines and pizza delivery boxes that have worn the characters' faces, it feels intimate. I still remember watching it via thrifted VHS tapes alone in a dark room on a CRT television, like the elder millennial stereotype that I am. Even after the sequel films, the Rebuild of Evangelion, Shinji, Rei, Asuka, and the rest still feel rare. Seeing Shinji's cute dopey little face fills me with a comforting feeling. That's what he's supposed to do, I realize with some dismay. He's my favorite corporate mascot, like Jotaro Kujo after him and Hello Kitty before him in my heart of hearts.

(I will admit that I was tempted by the Jotaro-branded cosmetics that came out to promote the release of the Stone Ocean anime. He is beautiful and immaculate, and I am but a simple creature who loves a good purple eyeliner.)

But I don't really care about the products, you know? Yes, I have my collection of small plastic Shinji Ikaris and Kaworu Nagisas from Sega, Bandai, and Good Smile. Sweet-faced little plastic boys and young men, with big goofy eyes and smiles. Sometimes wearing school uniforms and others traditional Japanese clothes, their sightlines almost always directed toward one another. Hands extended, gazes meeting. I still want the Radio EVA figures with the characters modeling contemporary streetwear because I'm a stereotype in more ways than one. Other than the figures, these icons I arrange neatly on my shelves and gently blow the dust off once every week or so, I don't care about the glut. The interconnected universe of pachinko machines and rollercoasters and socks. It isn't real to me. It doesn't inspire me to purchase Evangelion canned bread or Rei Ayanami power tools. I still don't get what the Unit 01 and Unit 02 crayfish figures were about, but I certainly won't buy them, no matter how often Instagram shoves ads for them into my face.

(I will also admit that I have been tempted by the official Rei Ayanami Blythe doll that came out some years ago. However, I don't have $400 to buy it on the secondhand market, and so we're moving on.)

All of that said, I am still easily suckered by narrative Evangelion spin-offs and media. Not so much the console games and life simulators, of which there are many to play across the decades. Certainly not the mobile games, either. But I have spent a not insubstantial amount of time tracking down the licensed and now long out of print manga spin-off titles over the years.

Because…I love Evangelion.

I'm beginning to realize my mistake.

Who in solitude, who in this mirror

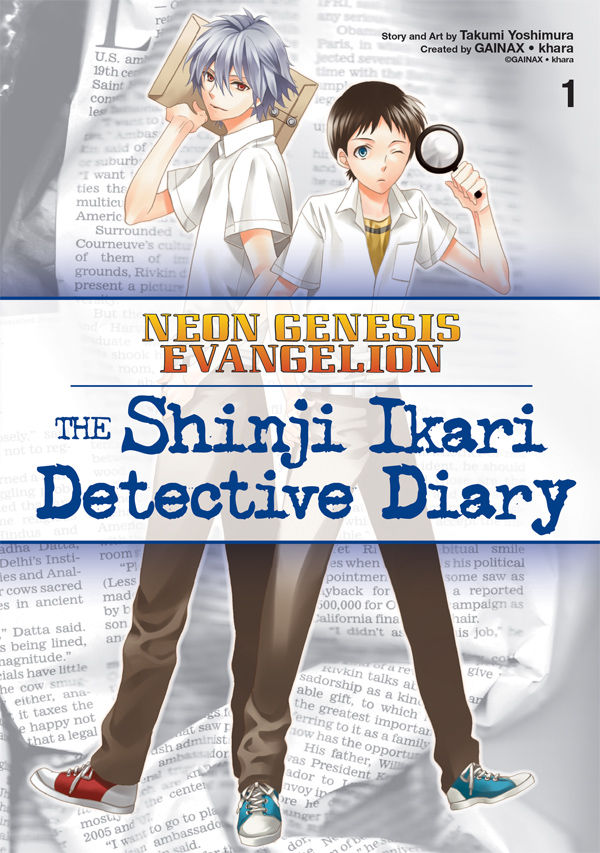

The Shinji Ikari Detective Diary is a manga from Takumi Yoshimura. It reimagines the Evangelion story as a low-stakes middle school action comedy, as is common with spin-off media. Ryoji Kaji is a private investigator who employs Shinji and Kaworu to help take on cases, leading to various hijinks. Rather than piloting Eva units, people basically have magical soul-powered sidekicks, more like JoJo's Bizarre Adventure stands than any mech.

A slim two-volume series, it was first published in Asuka magazine in 2010. It was later published by Kadokawa Shoten from 2010 to 2011, then brought to the US by Dark Horse from 2013 to 2014. Detective Diary was one of a handful of titles licensed by Dark Horse during the initial release of the Rebuild films to create hype around the series for English-speaking audiences.

The promotional blurbs, website listings, and letters-to-the-editor sections in the back of each volume assure you as much. Promises to "expand the experience" of "the most famous anime franchise of the last 20 years" are goofy and heavy-handed. No matter how cheesy it comes off, the editors and translators involved seemed to be genuinely enthusiastic in that way that American license-holders and distributors of Evangelion products tended to be in the old days.

As for Detective Diary, it's charmingly silly. Shinji is grumpy and melancholy, not good with people but trying to do the right thing for those around him. Kaworu is a mysterious magical boy who has unusually strong feelings for Shinji. Though they have a rocky relationship from the outset, the boys slowly bond over the course of their investigations. Rei and Asuka appear to accommodate romcom gags designed to embarrass everyone involved. The cast solves mysteries and does battle with stands. The characters are not themselves, but that is the point.

Yoshimura's pencils are airy and light. The figures are soft and sweet-faced, but plastic enough for amusing visual gags. Tonally, it's a generally light-hearted romp. It shifts easily from goofy faces and jokes to the restrained drama of Eva stand fights rendered in big, jagged panels and dynamic pages. Characters settle into small, intimate, romcom-y moments and personal reveals that feel warm to read. Things never get too serious.

The characters are off-model, of course, given Yoshimura's softer style. This is especially true of Kaworu. Of all the characters, he reads like himself the least with his more generic shojo love interest presentation. (There is a noted discrepancy among representations of Kaworu across all tie-in and spin-off media, because his haircut seems to be a sticking point for everyone.) But I can recognize these characters at a glance. The gang's all here, filling their predestined roles without the sharp edges and rough relationships. No apocalypses here.

When I first picked up this book from some local resellers, a well-worn edition from a Palm Beach County library, I found it charming. The stories are goofy. The art is very soft and pleasant. It helps that my dumb ass is primed to enjoy anything that features Shinji and Kaworu getting into trouble after school.

In the artist's afterward from the second volume, Yoshimura states that this was just supposed to be Evangelion with a happier ending for everyone. And that's fine. That's what it was contracted to do. It's content, to relate it back to that opening quote. It's competently made content by an artist who seemed to have fun with the ideas at work.

And as content, it's just supposed to be a light, fun, satisfying read for Evangelion fans.

But I don't agree.

Who in these realms of love, who by something blunt

The Shinji Ikari Raising Project is a manga series by Osamu Takahashi, and a life simulation game and romcom of the same title. There were two games in the Raising series, one for Rei and one for Shinji, wherein you step in as an overseer or guardian to "raise" the characters. The fairly lengthy manga was originally serialized in Shonen Ace and published by Kadokawa from 2005 to 2016. Dark Horse first brought it to the US in 2009. It loosely follows the premise of the "Campus" route of the game and shares many plot divergences from the anime with another manga spin-off (itself another video game spin-off) by Fumino Hayashi, Neon Genesis Evangelion: Angelic Days.

Like Angelic Days, Takahashi 's Raising Project manga explores the alternate timeline featured in the last episode of the anime, which dropped the cast in a light romcom setting. Shinji and Asuka are friends and next-door neighbors. Gendo and Yui are both present in Shinji's life. Rei is the mysterious pretty transfer student. Misato is the hot homeroom teacher. Everyone bickers and cracks jokes and runs to school late with toast in their mouths. This is the way things could have been in a kinder, gentler world.

Raising Project captures the good vibes and atmosphere of the first half of the anime, following Asuka's introduction. It's silly and downright domestic in many of the same ways that the show was. The intimate moments spent sitting in Misato's apartment sharing meals, or the tense, frustrated feelings simmering between Asuka and Shinji. Asuka is Shinji's best friend and neighbor, though she harbors stronger feelings than her blustering would lead him to believe. Shinji alternates between getting into trouble with Toji and Kensuke and getting into trouble with girls, floundering through every tropey school romance beat. He likes Rei and Rei seems to like him, but Asuka won't have it. Kaworu shows up eventually as a conniving romantic rival, which, I mean.

Feels weird, but okay.

Takahashi's artwork is really pretty overall. The visual flow across pages is so dynamic even when nothing is really happening, rendering the heightened emotions of tweens with equal parts bombast and tenderness. Takahashi captures the settings and characters really well here such that it feels convincingly like Evangelion, even as the tone drifts wildly toward comedy and romance.

For as cute as it is to see all the kids messing around at school, going to festivals, playing games, and feeling their feelings, there is an emptiness here. Not quite as immediately stark as in Detective Diary, which diverged so dramatically from the source material that it was jarring, but an emptiness nonetheless. The Raising Project spans 18 volumes and gets into NERV and Evas and SEELE, but I couldn't bring myself to continue to the end. Yes, things get a bit heavy and weird in that very Evangelion way, tipping into the absurdity that was always present in the anime and later Rebuild films. Yet I couldn't get into it.

And I think I'm kind of mad that I read it.

That doesn't make sense, does it?

The thing is --

Who by high ordeal, who by common trial

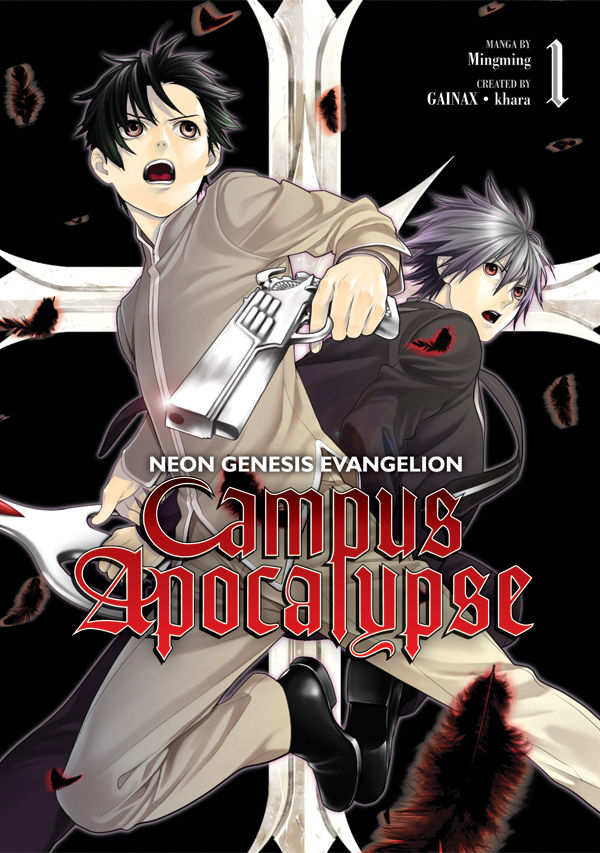

Neon Genesis Evangelion: Campus Apocalypse is a four-volume manga by Ming Ming. It was originally serialized in Monthly Asuka from 2007 to 2009, then published by Kadokawa Shoten before coming to the US through Dark Horse in 2010. Advertised to US readers on sales channels as "popular," the omnibus plasters "Evangelion has reportedly grossed over 150 billion yen, or approximately 1.2 billion USD" under the author information section, which certainly started off my reading experience with a bad vibe.

Campus Apocalypse tells a different but altogether very familiar kind of Evangelion story. It blends elements of Norse mythology with the franchise's infamous name-dropping of Christian concepts and iconography to create a distinct flavor and framework. The kids all go to NERV Foundation school and get up to regular middle school business as a mystery plot unfolds around Shinji's classmates, Rei and Kaworu. Angels operate more like the demons from CW's Supernatural than the strange and unknowable beings of the anime. They possess human bodies and take over human lives to advance their reality-warping plans, complete with quippy dialogue and dramatic fashion choices.

Like in Detective Diary, Evas are swapped out for manifestations of spirit or will, in this case opting for weapons. Each child gathered together to battle the angels summons a weapon from within: Rei a lance, Asuka a whip, Kaworu a sword, and Shinji a gun.

I think there's something interesting in giving Shinji a gun. A gun is a symbol of power and, frequently, masculine violence. His struggles with masculinity and self through both violence against and submission to others in the anime ring very true in this idea. In picking up a gun, one becomes an agent of their will and enacts it upon others. Giving Shinji a gun makes him powerful, but he still must wrestle with the realities of power and violence. He has violent impulses, but also desires to do violence in service of others. To protect and defend rather than perform acts of violence for its own sake. However, the series isn't exactly as clever as I want it to be.

Ming Ming's art is clean and pretty and dynamic. The figures have wide-set eyes that look just a little haunted, just a little alien. It leans much less on the school comedy elements and much more on the sci-fi/fantasy, but its shojo trappings drip off the page. The sweetness of titled heads, sidelong glances, and brushing fingers in moments of respite are so lovely. There's a soft, dreamy haze over stretches of the story, slowing everything down to indulge in the moody atmosphere of dark alleys and ominous cathedrals. I would be lying if I said that I didn't mostly pick up the omnibus for the gorgeous way Shinji is drawn.

I just…I really love Shinji.

Campus Apocalypse feels like its own entity while still playing with the language of Evangelion. It was definitely an interesting read. However, I'm bothered by it. I tried not to be, but it's bothered me more than it should. I think it comes down to a single page, early in the first volume. Shinji, holding the gun manifested from his will, fights with his feelings. Telling himself, with closed eyes:

"I mustn't run away."

The impulse to fight.

"I mustn't run away."

The desire to flee.

"I mustn't run away."

To stand his ground and do the right thing.

"I mustn't run away."

And he stays.

And I nearly threw the book across the room.

And who shall I say is calling?

When I originally conceived of this newsletter piece, the one you're reading, I thought I would keep it simple. Keep it breezy. Just discuss some Evangelion spin-off manga in my collection. I had read a bit of it before and thought it was rather charming, so what's the harm in revisiting it?

As I discovered throughout my reading, it's less a matter of harm and more a matter of questions I don't have answers for.

I feel that I must preface this next stretch by saying that, no, my intent is not to measure spin-off material against the anime. That's fruitless. More than that, Evangelion is far too weighty a stick to use against a handful of contracted artists making some comics for a paycheck. Whatever their successes and failures, these series are art that are allowed to exist, and have merits that are worth discussing. They are the products of talented craftspeople who managed to create something worth talking about on its own terms.

But those terms are…complicated for me.

Because I have to wonder what these stories are for. What they're doing. What they're saying. What they aren't saying, rather. As part of the media mix, they exist to do two things:

Promote the Evangelion brand to fans who are primed to buy more content and products about these characters.

Make money for everyone involved in the production of these works, based on that brand recognition.

There is a humanistic argument to be made that these stories exist for the comfort of the reader, the fan expected to buy them. Because I do take Detective Diary artist Yoshimura at face value in volume two afterward -- this was a story designed to give the Evangelion cast a happier world and ending. I am completely certain that Japan's cultural relationship to apocalypses both real and imagined shapes the desire for softer alternatives in a way that I'm not privy to as an American. In fact, the presentation of a softer alternative appears to be the marching order of the franchise since the foundation of Studio Khara and the production of the Rebuild film series. A kinder, gentler, more accessible, more profitable Evangelion.

None of this is to say that Neon Genesis Evangelion was a completely artful endeavor devoid of filthy corporate incentives before this period. (Insert "lol" at the history of Gainax here.) The animation industry is not a charity for artists. The mecha genre itself is directly tethered to and responsible for advertising highly profitable toys, figures, and model kits. Members of the production have gone on record about the various mercenary decisions that have shaped the franchise. I think we've all heard the quotes about how they made Rei and Asuka specifically to appeal to the differing tastes of male audiences for a greater fan investment. Hell, Anno has built a brand as an otaku who made it to stardom, a fanboy who gets to play with his favorite toys for all of our enjoyment. The merchandising, licensing, and mythologizing has always been part of Evangelion's history. It is what it is.

It certainly worked on me, didn't it? My apartment is full of framed Evangelion art. I have the latest releases of Neon Genesis Evangelion and End of Evangelion on Blu-ray. I clap like a dingus for all the publicity stunt material that positions Hideaki Anno as Our Benevolent God-king Fanboy. Over time, I have amassed a small collection of Evangelion figures, stickers, and kitschy imported goods. (Some licensed, others not, I admit.) I own a Unit 01 motocross shirt that I found for $15 at Boxlunch for no reason. I spent time and money to track down out-of-print manga simply because my favorite characters are in it. I uphold my end of the bargain. They made it and I bought it.

So…now what? What do I do with these stories? What are they supposed to mean to me?

Because yes, it all fulfills the requirements of a spin-off. The characters slot together as expected, but I am not compelled by it. Shinji grumbles about those oh so silly and reckless adults because hey, remember the anime? Remember Misato? Shinji becomes fascinated and enamored with Rei because hey, remember the apartment scene in the anime? Asuka is a loud mean girl because hey, remember how she and Shinji are in the anime? Kaworu likes Shinji a little too much, a little too fast, because he's a little too strange for a guy, and isn't that weird? That's weird, right? You remember Kaworu and Shinji from the anime, so you're going to buy the manga for Ming Ming's beautiful color covers of Shinji and Kaworu together. You're going to buy the silly middle school detective book.

Shinji says the line:

"I mustn't run away."

But it means nothing. They are empty signifiers. Catchphrases. A checklist of traits. Shinji's struggle between fight or flight. Rei's loneliness. Asuka's rage. Misato's failures. Kaworu's love. It's familiar, and you're supposed to respond to it. Nothing really means anything, and you feel a little sad reading it, even though you're supposed to laugh. Or think it's cool. Because it's cool. Or funny. Or goofy. Or romantic. It's what you wanted, all the characters you love with none of the suffering.

None of the ugly stuff.

Because we're not supposed to think about any of it.

You're just supposed to have fun.

Have fun, and spend money.

Evangelion is fun.

But Evangelion isn't fun. It certainly can be, in those earlier episodes before the series got too heavy. The domestic hijinks and frustrated romantic moments between Shinji and Asuka. The kids all hanging out at school. Misato and Ristuko and Kaji being burned-out adults who can't get their shit together. This is the humanity on the line, these connections and quiet evenings, before everything spirals into abject despair.

There is no humanity in works like these, not really, because there's nothing to make their worlds worth saving. Evangelion is the story of a war, however nebulous the battle lines, its pilots little more than child soldiers. Many of the main cast are named for battleships, to make the concept of war itself seemingly inseparable from their identities. It's more of a war of the soul and the mind, of course, but I'm the kind of viewer who never took the story's events quite so literally. In these spin-off works, the characters exist as wind-up toys, performing classic lines and affectations for our entertainment, without the slowly unfolding apocalyptic context to ground them. I must simply imagine Shinji Ikari happy, free of cycles of struggling and pain.

But I do imagine Shinji happy through his struggles. Shinji strives and fails and discovers the capacity for happiness, for connections, for life, through the story he and his friends were designed for. The story they were designed to tell before they became solely content, because Shinji does discover happiness in his life by learning that he is not alone.

I find happiness in his struggle.

I am comforted by it.

I am enriched by it.

I return to it, again and again, to imagine Shinji happy. We are like Sisyphus in that, I think. Yet I am content in that relationship.

So then, with these books in my hand, having done my part as a fan, as a consumer of Evangelion content, opening my wallet as instructed, I must ask: what is this for? Because if it's to comfort me, I am made uncomfortable by it. These are empty worlds filled with ghosts. A Shinji-shaped person, in Shinji-like clothes, who assures me, limply, that he is happy.

If it's simply to make money, I guess it did that well enough. Evangelion is worth over a billion US dollars. The hamfisted English marketing told me as much, promising that I was buying into something popular and profitable. Despite the assumed values of its audience, I don't like Evangelion because it makes money. I like it because it's a weird, sincere, messy, conflicted, artful thing, meaningful for what its creators poured into it. For the meaning I found in it.

And these books are…fine. They don't offend me. I'm not actually mad at them. They're content, like everything else companies tell us we want. They are just as much an escape from reality as Evangelion is, though I feel the reality they attempt to escape is Evangelion itself. That's strange, isn't it? These stories feel…confused. Self-defeating. They read to me as attempts to negotiate the terms of something that is, in itself, about confronting pain to find catharsis. In stripping themselves of that specific context, the characters are left empty. The stories used to fill them instead, however much they borrow from the language or aesthetics of Evangelion, just leave me feeling cold.

I can't help but think that all of these stories, all of this effort, would have been better spent on something else. Works unconstrained by the character checklists and familiar interactions. Someone else's middle school romances or detective stories. In being so hamstrung by the material it exists to help its fans escape, I find myself with a pile of books that puzzle me as to what I should feel about them.

If the point of Evangelion content is to imagine Shinji Ikari happy, then that point is lost on me.

Evangelion, for all the flaws and cracks in it, makes me feel that better things are possible. That we can be happy if we push past the clamor of guilt and shame and fear that haunts us. We can reach out to others. We can live beyond the things that try to kill us by creating connections to the world, and that those connections are worth fighting for.

Dying for.

Evangelion content just makes me feel that I must avert my eyes to find peace. I choose to take my comfort as Sisyphus does. Because I love this story and I love these characters, and their suffering is as meaningful to me as their happiness. More so, perhaps, in the depths of despair and isolation. I admit that even without the now numerous resolutions to the story, I still love these characters for the realness of their pain, because it's felt so much like my own throughout the course of my life.

To see it laid bare is…well, it's the reason I keep writing about Evangelion.

But even that is Sisyphean, isn't it? Talking about comfort in stories. The correct comfort to take from stories. The correct comfort to imbue them with. The perverse desire to sit with characters in their anguish, like catching a reflection of myself in the black mirror of my television screen. I don't even approach art with the expectation of being comforted by it. It's just happenstance that Evangelion is comforting to me for the same reasons that it's uncomfortable for many other people. The reasons that others might seek comfort from a gentler Evangelion once they've finished with it.

At the end of the day, it's all just stories told by craftspeople, and they're all just products sold to me by companies.

The world is still on fire, and there are bombs falling every day.

I guess I just prefer stories that let the bombs fall rather than pretending they were never really there.

References, Citations, and Further Discussions

Add a comment: