Tomie Kawakami and Her Cordycep Children

Gender, identity, and personhood in Tomie.

The more time I spend with Tomie by Junji Ito, the more I think she's my favorite monster. Perhaps, upon completing my recent reread of the dense collection of shorts that make up her story, I'm willing to say that monster is too strong a word for Tomie. There are a lot of words that I could, and frequently do use, to describe Tomie. Conniving. Sadistic. Childish. Unpredictable. Monstrous.

But not a monster.

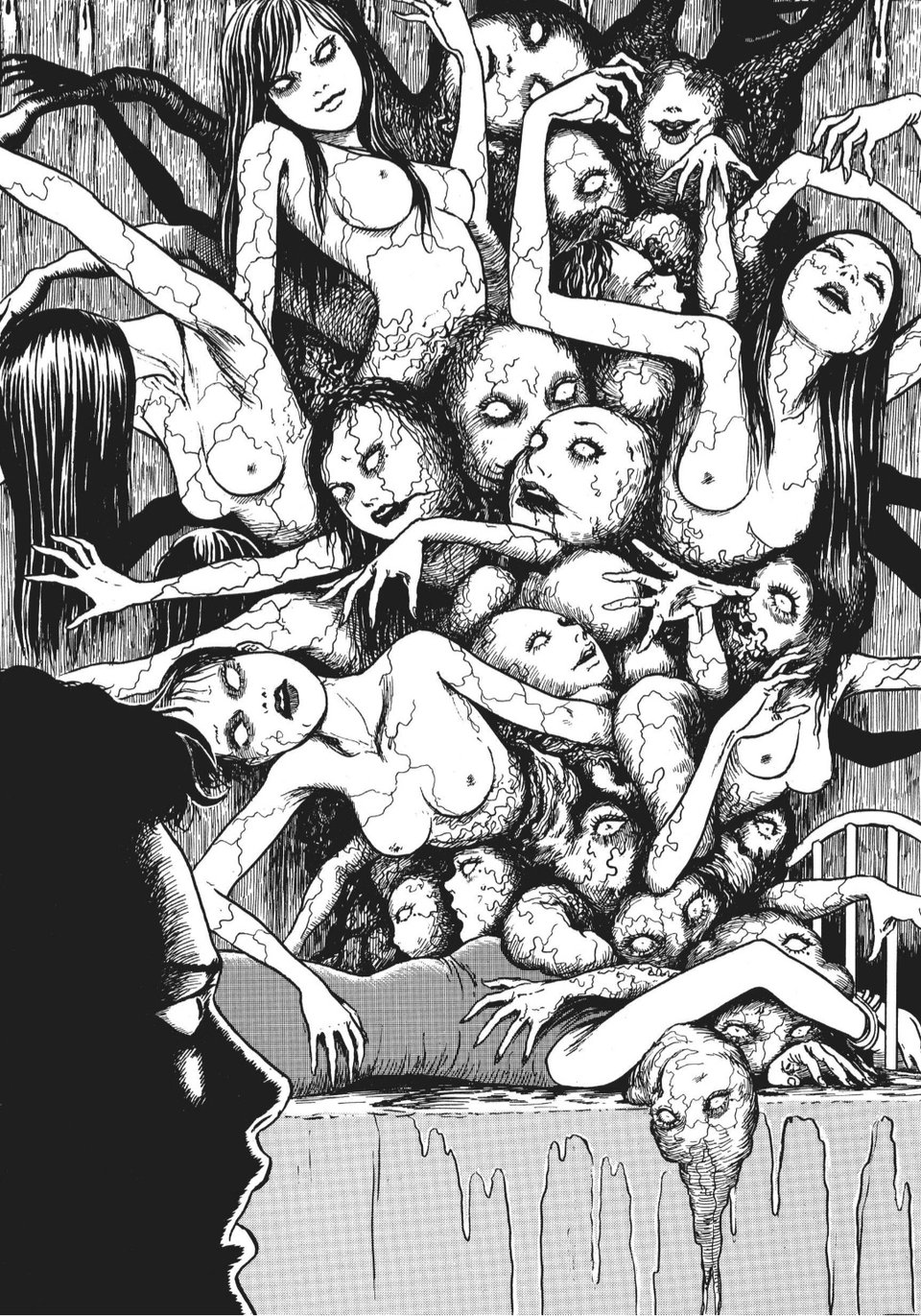

I feel too strongly for Tomie to ever see her as a monster. I think there's too much of myself in her pale grasping hands and mass of blistering, distended heads. The bulbous extremities of her contorted form feel familiar to me the longer she stretches out across a page, whether emerging from a puddle of her own gore or the mind of her lovesick victims. Spindly offshoots growing from hairy, pulsating bits of hacked apart flesh remind me of the different shapes I've taken in my own life. They are sometimes as ugly as she is, as wretched and malformed, and yet…they are me.

Tomie is just like that.

Within Tomie, I see a rupture. Within that rupture, there is a space to make new monstrous meaning.

I struggled with writing this piece for the better part of a year. The idea leaped out at me one day at the grocery store, of all places, wandering down an aisle as the corridors made from tightening shelf units funneled me toward the long cosmetics aisle. I examined the selection of false eyelashes, a thing I never buy.

As I grow older, I've developed an instinctive fear around the safety of my eyes, one born from random health scares and allergic reactions to makeup. Seeing the optometrist is scarier now than it's ever been, and the idea of gluing plastic fibers to my eyelids sounds kind of horrifying rather than merely troublesome or dull.

As I examined these things I never buy, for some reason, I thought about Tomie. I thought about how much Tomie and the performance of femininity feel closely linked. It seemed so obvious then, as real as the package of legally distinct Beetlejuice-esque black and green fanned lashes in my hand.

“I should write about that,” I said aloud to myself. “Maybe that would be interesting.”

I put the lashes away and I wandered off to the other side of the store for whatever it was that I came there to get. By the time I paid for the handful of items I carried to the self-checkout, I had already decided that I needed to hold off.

This idea was kind of vague.

Kind of boring.

Kind of obvious.

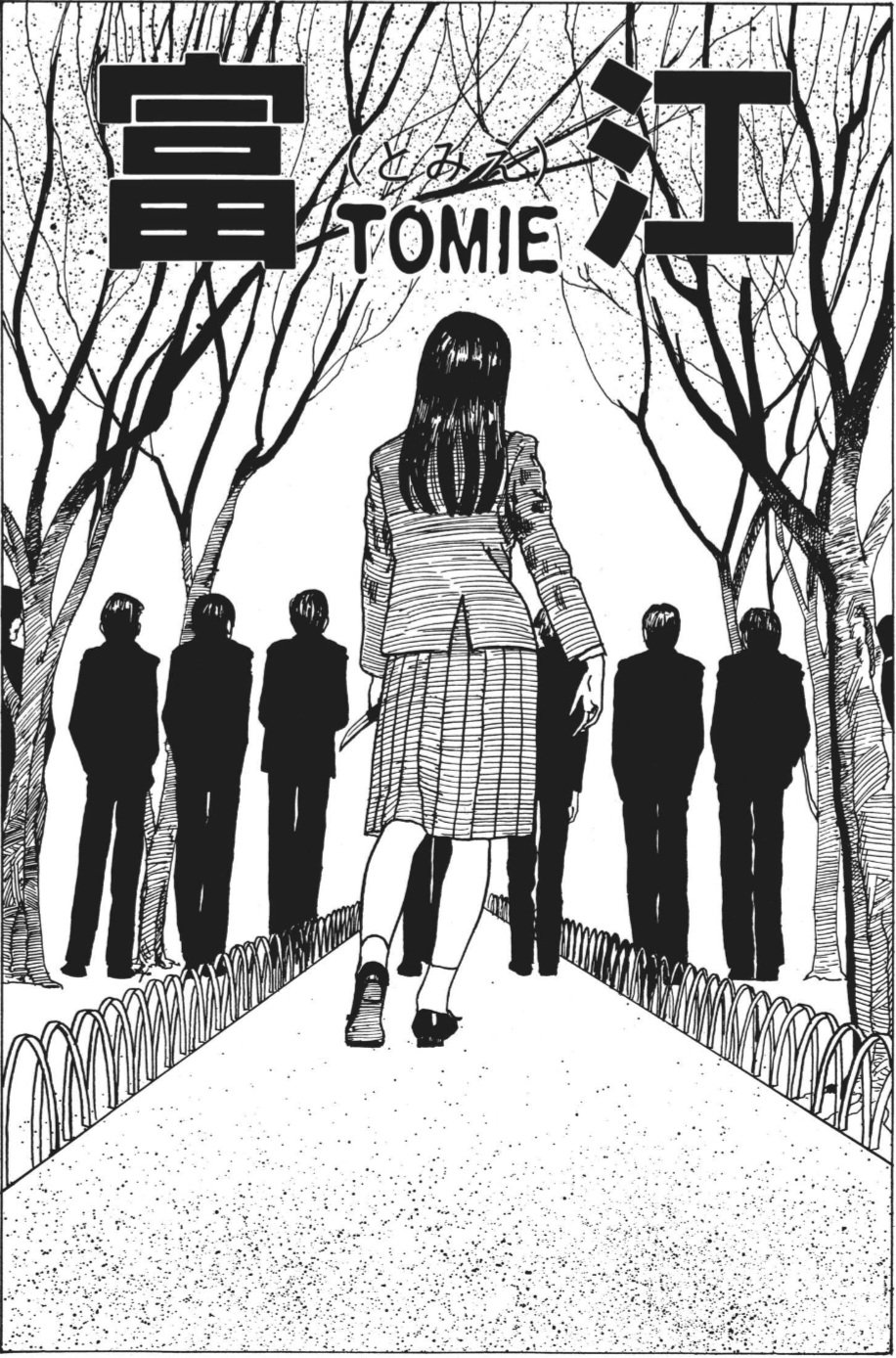

The vision of Tomie Kawakami I always encounter as manifested by the popular consciousness is one of feminine rage. Her cunning and cruelty are almost aspirational.

“Aren't you tired of being nice?” asks the sweet-faced schoolgirl. The demonic face erupting from the side of her skull grins and asks: “Don't you want to be bad?”

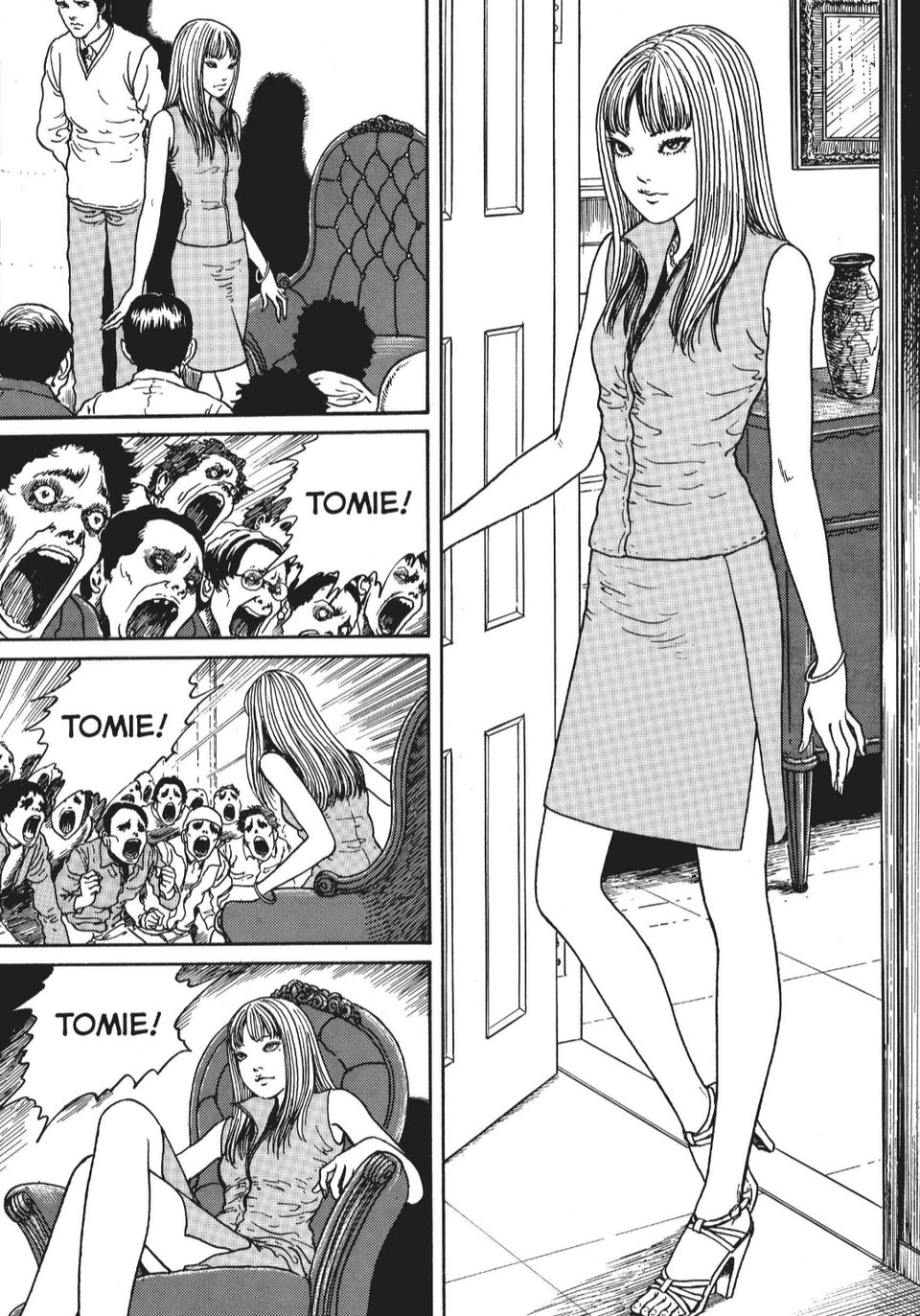

Tomie is monstrous and beautiful. She drives men mad with jealous obsession so that she can feed off them. Literally and materially, a psychic and social parasite. She eats caviar and foie gras and wears designer clothes and diamond rings. Whatever Tomie wants, Tomie gets, and every man is just a means of sustaining herself.

Girl, get the bag, you know? Do what you have to do. The world will rip you to shreds, so you may as well enjoy the ride.

But that's just it. Every man is doomed to kill her, and Tomie must move quickly so that she isn't the target of that possessive frenzy. Over and over, men are driven to murder her and destroy her body, hacked up or beaten or bludgeoned into dozens, hundreds, of pieces. An entire person reduced to an ominous black stain on a carpet.

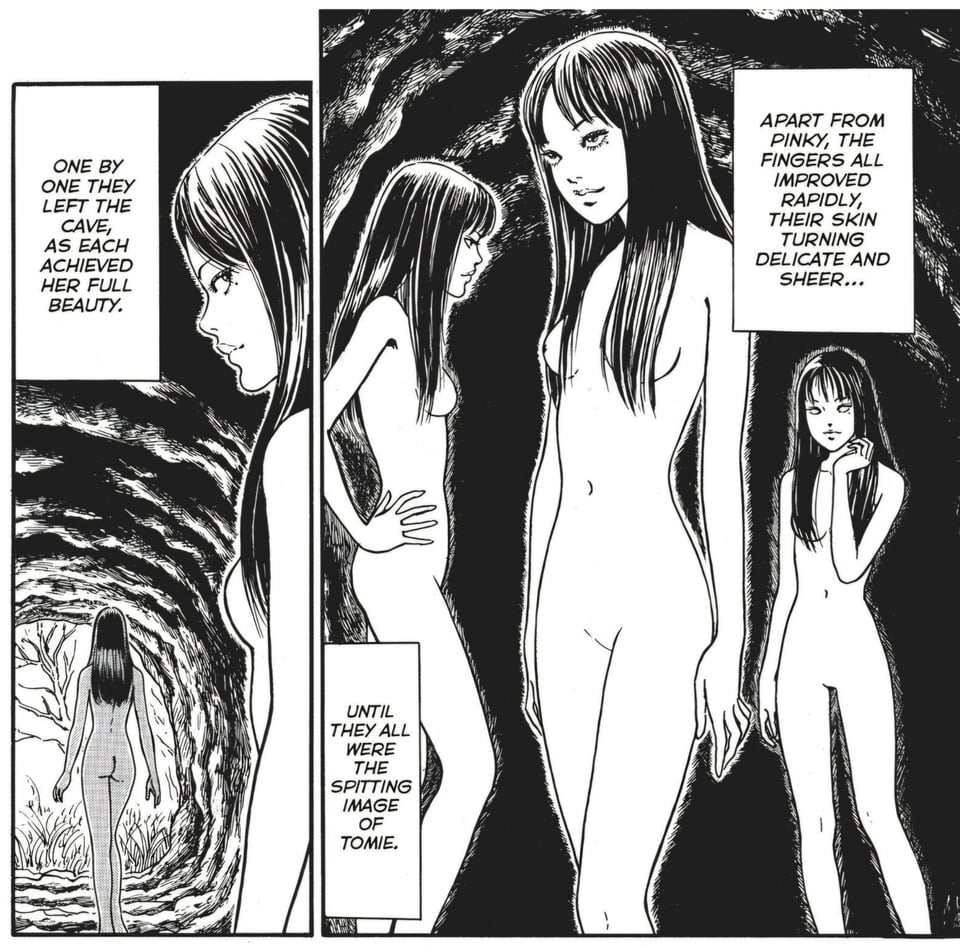

Over and over, Tomie comes back, born again in asexual reproduction from her own blood and flesh. Every Tomie has the same personality and survival instinct, tethered to her sister-mother-clone through their shared drive and desire to assert dominance.

Tomie is also a girl. Cruel and eternal but still just a girl of fifteen. Survival pushes her to team up with her own abuser, the teacher who impregnated and murdered the first Tomie Kawakami, pretending to be his daughter with few other resources within reach. She inserts herself into schools as a student to torment other teenagers for her own amusement. She moves in on an elderly couple longing for a daughter and an old man as his teen bride, pitting her new teen step-sons against one another as an incestuous mother-figure.

She takes over an old man's house by holding him and his daughter captive to assume her identity. One couple takes in her pieces as their malformed baby and engages in horrific acts at her bidding. Young and teenage boys are manipulated into killing people (and themselves) for her. At least one boy is irrevocably harmed by her predatory affectation while “playing” as mother and son, sending him down a path of obsession and violence that he never recovers from.

Tomie's first death and dismemberment at the hands of her abuser has locked her into this state of perpetual youth and unending life. Whoever, whatever, Tomie Kawakami was before death has been replaced by the cruelty, and at times depravity, of her offspring. It's ugly, but it's rendered with captivating pathos by Ito, as Tomie revels in both the supernatural beauty she embodies and the horrors she's capable of.

The mystique of both the monstrous nymphette and the vengeful feminine made Tomie feel just a bit silly to write about. I've already written about her through that lens, after all. She's not for me the way she's for women and girls who take the same very pointed meanings from her.

There's a sense of reclamation within Tomie's story. And I get why. It's a striking image: a girl unbound by social constraint and gendered expectation, asserting her agency in a world that has stripped her of it by taking everything she wants.

But I think there are still nuances to Tomie that get lost amid the Hot Topic t-shirts and keychains, the plushies and the ball-jointed dolls. It's easy to look at Tomie in her totality as a multimedia intellectual property, with her own manga, film series, anime, and merchandise, and gloss over the murkier details. That's how these things tend to go.

At the end of the day, I have to pose the question that's been nagging at me since that day at the grocery store. If I don't, it'll drive me nuts.

Can Tomie still be a girl if she feels like something else?

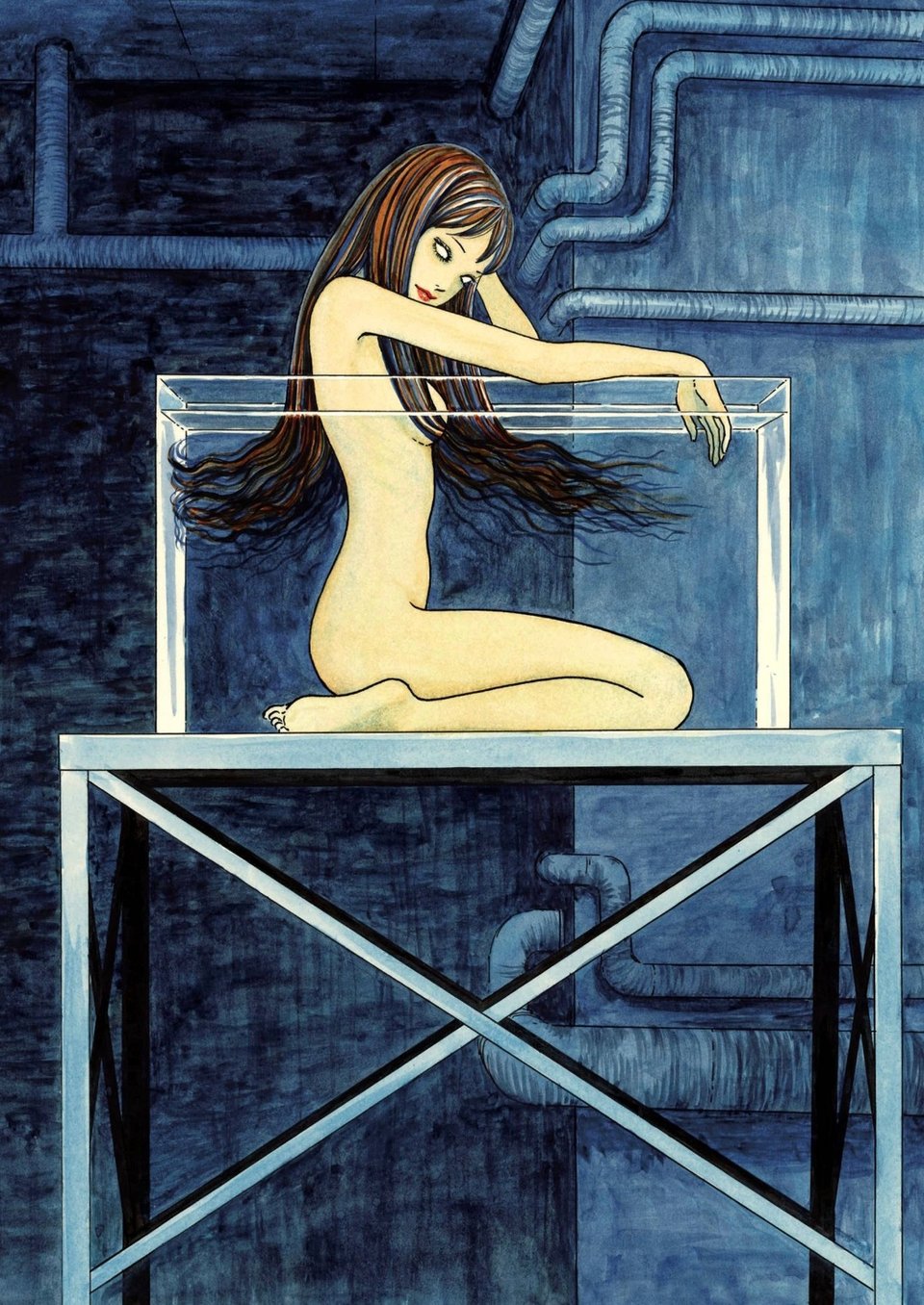

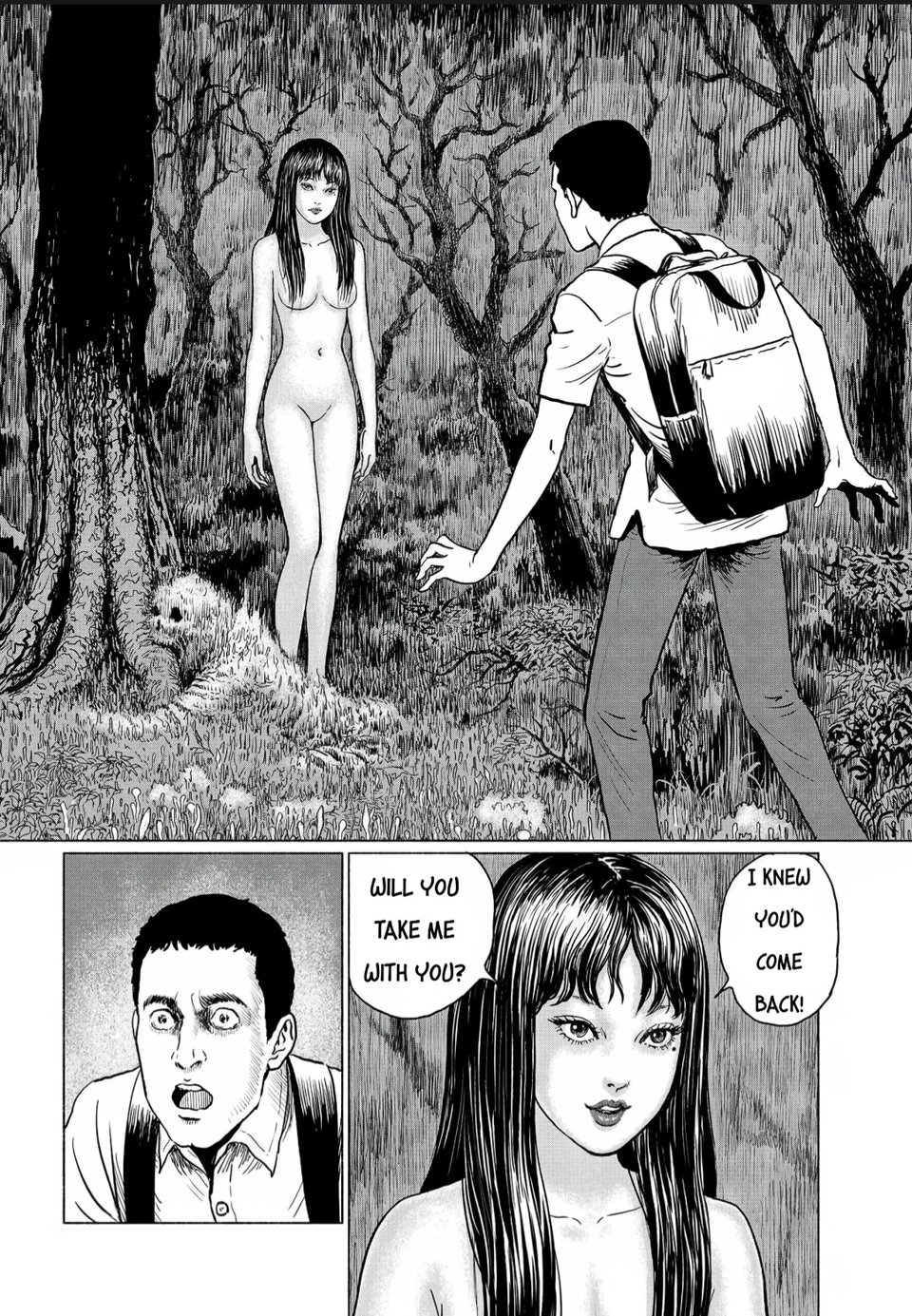

Though an object of men’s desire, with many men acting as the subjects of these stories, Tomie's frequently nude body is rendered on the page with a kind of pointed neutrality. I think back to her depictions in Basement, Little Finger, and the most recent chapter, Control. Breasts covered by the fall of her hair and the space between her legs smooth and featureless, Tomie feels…

Androgynous?

Ungendered?

That stands out to me. The implied leering, the penetrative gaze of male characters sick with desire, is neutered by Ito's pen. She's neither sexual nor fully in possession of gendered signifiers. I don't think that's simply a matter of Ito prioritizing the body horror he relishes in instead of sensuality. A stylistic choice, sure. Perhaps it's a kind of self-imposed censorship or demonstration of restraint. I'm not so sure, though.

Tomie is as pleasing to look at while undressed as she is clothed. Ito is very capable of drawing beautiful figures with beautiful bodies, after all, men and women alike.

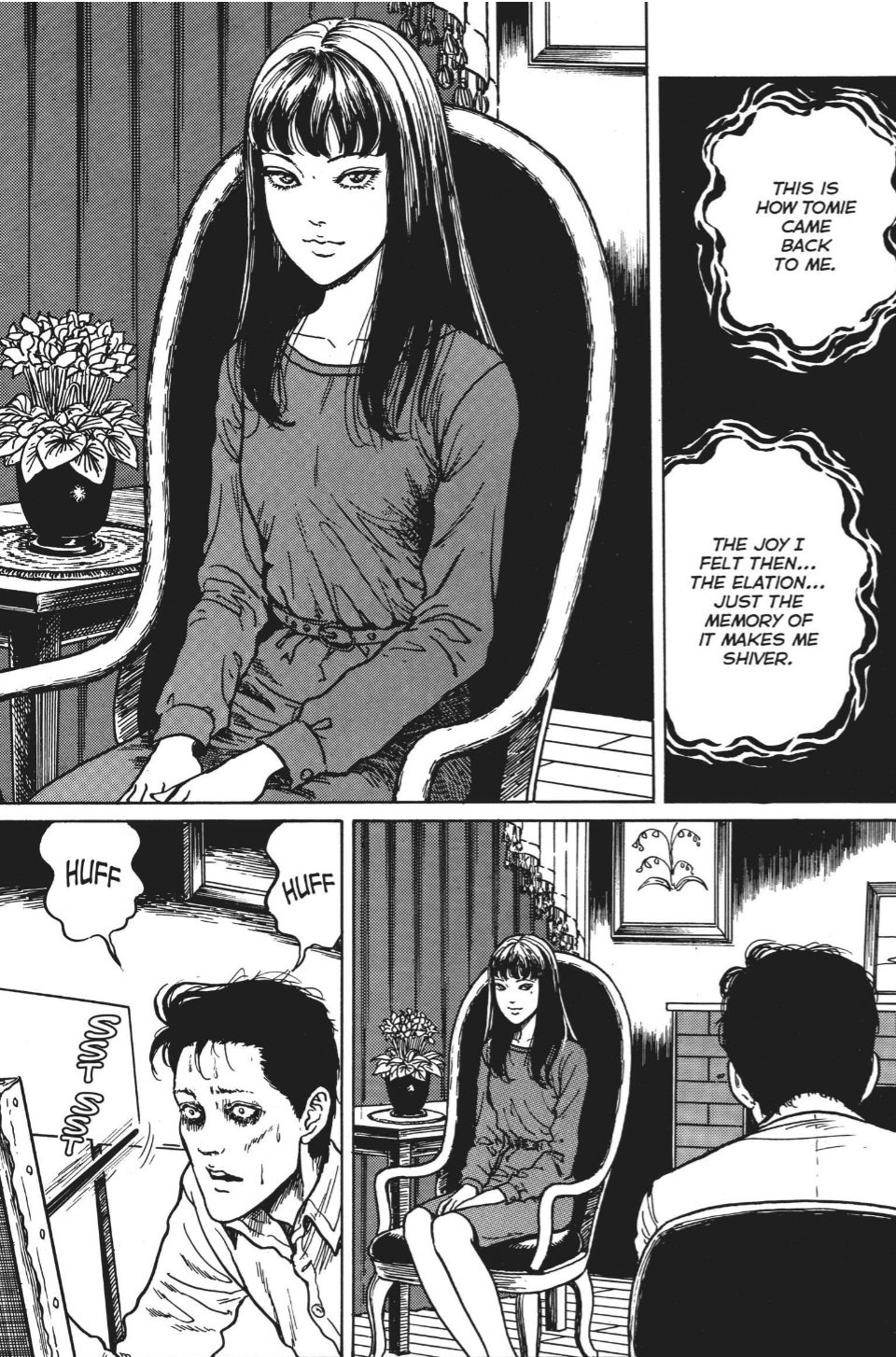

Yet Tomie is at her most beautiful, her most desirable, when she's clothed. In control of the situation, arranged comfortably in an armchair or posed for a painting, she smiles and toys with her chosen prey. She looks elegant. She looks confident.

She looks powerful.

You can look at Tomie because Tomie has nothing to hide. You aren't given the chance to eroticize her, because her body is never eroticized by the narrow, highly subjective points of view we follow throughout the anthology. She is nude, but never truly naked. There's an interesting tension in that choice, I feel.

On one hand, I think it's easy to see her nudity as a merely perfunctory part of the story, but I take another meaning from it. When her breasts are uncovered, she's often in a monstrous state, reaching out to a victim with an empty, hungry stare. She turns the sight of her own nude form into a jump scare.

The act of looking is the act of seeing the horror of Tomie in her totality. Otherwise her anatomy is vague, more like a doll than a person. More like an ungendered being than a woman.

Tomie doesn't give birth. Her body can no longer become pregnant, capable of reproducing only herself in a parody of motherhood. So why would she need such defining reproductive features? Tomie doesn't fulfill her role as a woman, so why would she pretend? Is she a woman? Does she need to be?

Tomie simply is, existing on her own terms.

There's a kind of power in that.

In the three-part 2018 arc Takeover, Ito delivers another story that I find myself constantly turning over in my mind. The protagonist of this story, like so many others, sees Tomie on the street and is instantly smitten with her. He must possess her in all her beauty and so he does, quickly becoming her suitor. Their courtship is short-lived as Tomie's bratty, demanding nature rears its uncharitable head.

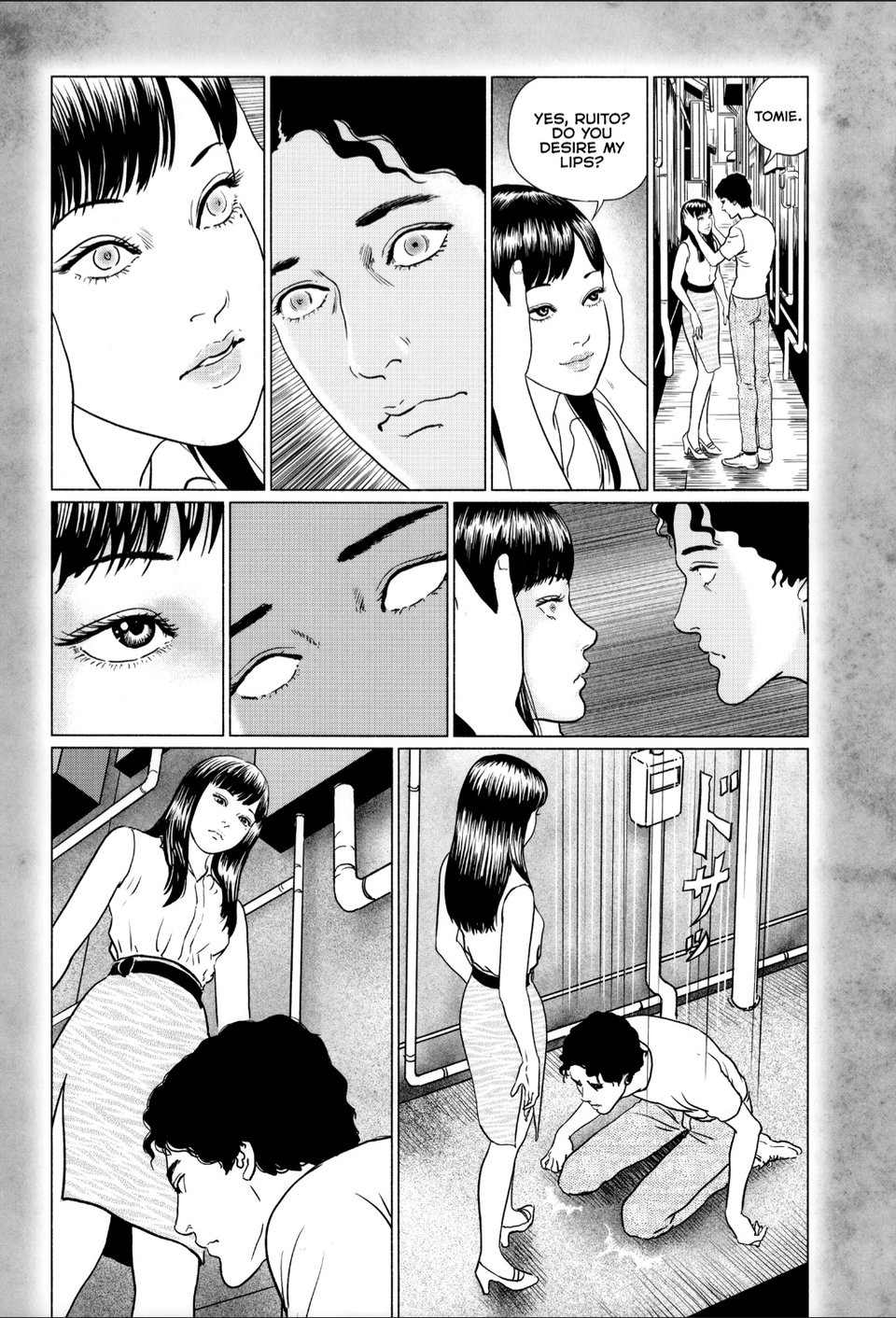

However, instead of killing Tomie, the protagonist decides to punish her in a new way. This scorned lover is an entity unto themself, a parasitic consciousness that jumps from host to host. Every time he -- they -- swap minds with someone, that person is placed inside the body of the last host, unable to escape. Watching people dissolve into madness inside unwanted bodies is a kind of sport to this entity, it appears, and they want to see Tomie suffer the same fate.

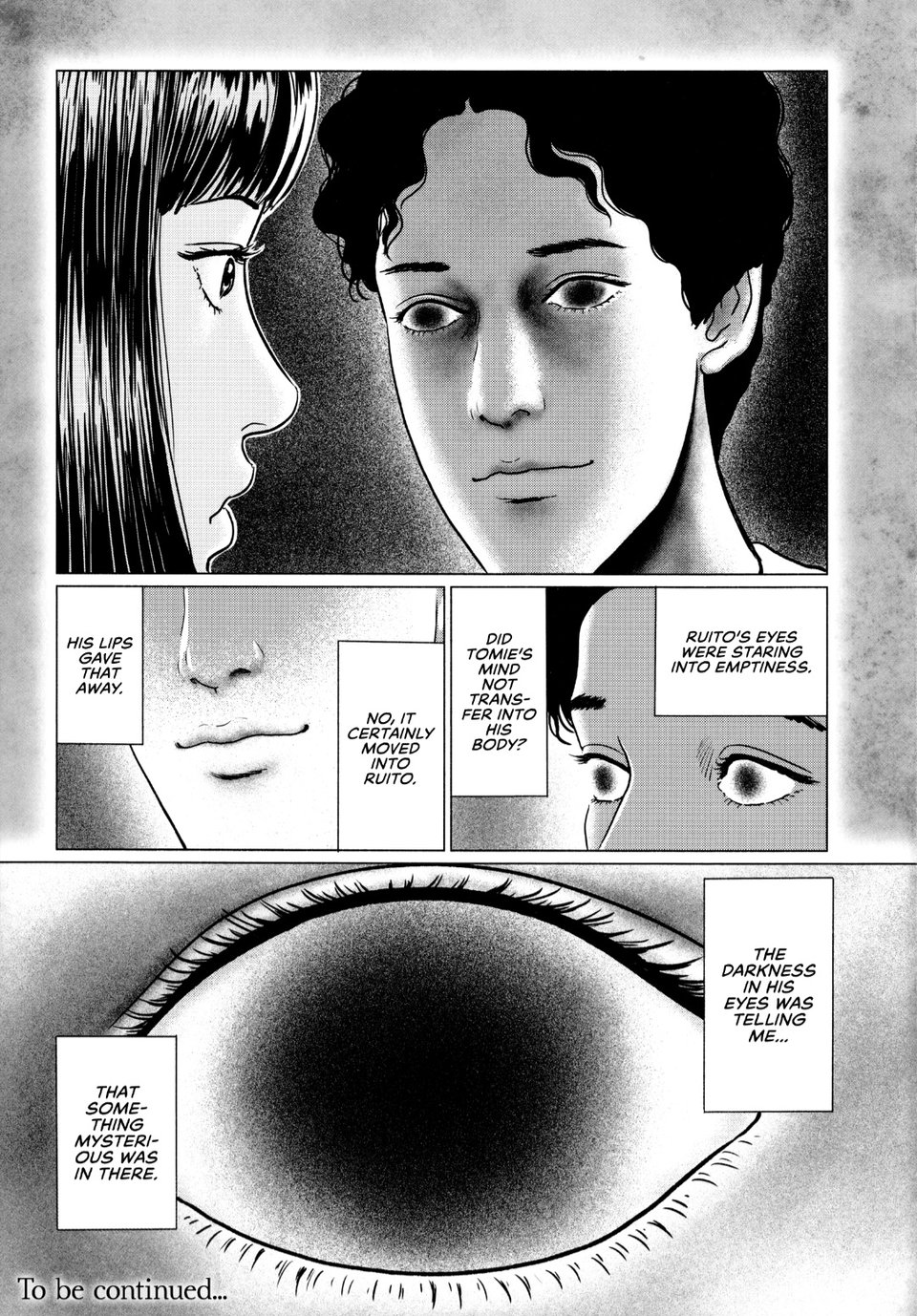

With a grim excitement, the entity takes Tomie by the face. They move their mind into her body and she into theirs. The entity is pleased with their beautiful new form, but not for long. Instead of being confused or scared, Tomie wears the man's face with a vacant smile. There is a black, lightless look in her eyes, something that wasn't there before.

She says nothing.

She smiles.

She turns and walks away into the crowd, vanishing on the street as if she was never really there.

Freed from her body, so too is Tomie freed from the curse or disease that turns men into killers. Tomie is unburdened by the terrors of girlhood and womanhood. Or rather, I think, Tomie is able to embrace a different kind of performance.

Perhaps this Tomie is better suited for such a life. Perhaps it opens the door to new and different terrors. Nonetheless this rupture provides new ambiguities to consider.

Because if Tomie isn't a girl trapped in a body that doesn't age, if she doesn't drive men to violence, if she doesn't perform her gender as a cog in systems that ultimately seek to destroy her, then who is she? Neither monstrous nymphette or avenging feminine, what remains of her?

Who can Tomie Kawakami become if she doesn't have to be a girl?

I think one of the most fascinating aspects of Tomie is that we never see sex. Implication and innuendo, sure, but never the act itself. Bodily fluids and lurid fantasies steep the story in a sense of kind of perverse sexuality, but it isn't titillating. Sex just happens at Tomie. It's endured by the reader as much as it is meant to be endured by her.

That's why I've always wondered if Tomie ever had sex with any of her targets, or simply held them at arm's length until she achieved her goals. It isn't a question of moral consequence but one of interiority. The pleasure comes from the hunt rather than the capture. She doesn't want sex. Attention, yes, but not sex.

On the occasion that she meets a man who doesn't want her, such as the suspicious step-son from Little Finger or the man still mourning his deceased girlfriend in Gathering, she goes to great lengths to secure their affections. Neither leads anywhere, but the men do succumb. One is left for dead upon his confession and the other is left haunted by Tomie in his dreams. Tomie gains nothing but a twisted satisfaction. She wins, even if she dies in the process.

Because sex never happens on the page, violence rises to take its place. That violence is two-fold. Men's violence reflects the inherent dangers of heterosexual relationships for women. The act of stabbing and dismembering Tomie evokes sexual violence through the brutality of penetration. In this way, Tomie is always seeking escape from both sex and death in all her relations with men.

And

I mean

Yeah

A part of me feels that in a big way. A much younger part of me, to put a finer point on it, from the ages of fifteen, sixteen, seventeen. Hell, even into my twenties. When I was a young lesbian terrified of being seen and pursued by men. When men went out of their way to leer, intimidate me, and try to get me alone. When a man chased me through a grocery store demanding my number. That version of me would have given anything to have the strength to crush them beneath my boot for how powerless they made me feel.

How weak.

How stupid.

This is why Tomie Kawakami can offer a kind of relief, even to someone like me.

And so this is the part of the essay that gave me pause that day in the store, looking at fake eyelashes. I feel like I'm making some kind of miscalculation, or failing to show my work on the page. Of course, this isn't a math proof. It's a story, and I'm a reader. Neither she nor I have anything to lose in this because there's nothing at stake. Even knowing this, I desire to be understood, and for my feelings to be understood, as imperfect and incomplete as they are.

So, I just have to say it.

In my reading of Tomie, with me acting as the reader and her the subject of that reading, she never quite feels like a woman to me. Tomie doesn't feel like she's trying to be a woman. Yes, she is a girl, and yes, there are infinite complexities and nuances to how people conceptualize, embody, and experience girlhood and womanhood. There is no one way to be a woman given the multiplicity of definitions across every corner of the globe. Being a woman is a value neutral act. It simply is and you simply are, and as a woman, your experiences of body and self are unique.

But with Tomie, it all feels a little different given the context.

Tomie functions as a kind of Ur Woman in her story. She exists to absorb the extremes of patriarchal violence and desire in her particular corner of the world. Rape, murder, incest, all very real threats. From daughter to mother, adult to child, she moves fluidly through these states to explore their upsetting contours.

Her stereotypical femininity is ratcheted up to an absurd degree within the text to contrast her with other, more traditionally feminine girls. The same way most men are portrayed as lecherous and violent, Tomie is vain, self-obsessed, and materialistic. Bitches do be shopping and all that. It's almost comical how evil Tomie can be, not only assured of her beauty but seeking to assert her place as the most beautiful.

In that theatrical performance of gender, we can see the farce at the heart of these extremes. The farce feels like the point of it all, intended or not. Tomie feels like she's inhabiting a role and projecting to an audience rather than embodying any hard definition of girlness or womanness. To men, she's bratty and boisterous and demands attention. Whenever she's alone, we see her seated on the ground or on a bed, tucked in on herself with her chin resting on her knees. She appears small and unbothered, like a curled cat warming itself in the sun. The performance falls away in those rare moments when she's allowed to be Tomie.

I admit that there is a cultural gap between myself and Ito, on opposite sides of an ocean and many years apart in age, but the song still sounds the same. Ito manages to present something that feels very true, amid the depravity and gore. His stories waltz right up to the line of blaming Tomie for her fate, letting the reader fill in that gap with their own prejudices, but don't commit to that moral judgment. Tomie is not innocent, but she wouldn't exist in this world if this world hadn't shaped her into someone driven to such extremes.

All of our experiences of gender and sex and the body itself are shaped by the world we live in.

That truth is why I can't help but come back to Tomie.

Through this tension in gendered performance and androgynous physical presentation, I feel some kind of way about Tomie. I see something familiar in her. I experience tension within my own body. Observing myself in the mirror, my own breasts and reproductive organ don't feel gendered. I don't look at my body and see a woman's. I feel further tension with sex and desire, things I don't really want and experience. Or particularly want to experience. I stand apart, by society's measure. I am something else.

The necessity of medical care requires me to check the Female box on an intake form. The political climate makes it the path of least resistance no matter how reflexively I twitch or wince when I check that box. My faulty hormones and internal organs didn't get the memo about my feelings.

I subject myself to questioning, poking, and prodding. Penetrative tools and strange looks. I have to explain that I don't have sex and I don't date men and I don't want to become pregnant and I still need care over and over. Doctors want to keep me fertile and accessible, despite my desire to be anything but. It gets to be humiliating after a while.

I'm a queer person in a queer body. Like Tomie, I am subject to the expectations of womanhood. Like Tomie, I've experienced patriarchal obsession and violence, though at a much smaller and less traumatizing scale. I've performed high femininity to appease and pacify others. I've performed it to please myself. I say words like “she” and “her” to describe myself when “they” and “them” leave a strange taste on my tongue. I want to look cute and recognizably feminine in a highly specific, curated way that satisfies only me. As I do this, people still project their vision for how my subjective experiences of gender should manifest.

Even in negotiating a space for myself outside of womanness or girlness, people want me to conform for their comfort. I feel a little like Tomie in the doctors’ observation tank, a thing suspended in fluid, studied and gawked at. Determined to exist on my own terms. Punished one way or another, whether I play the game or don't. Saying all of this makes it sound dire, of course. I don't walk around all day in a fog of gender confusion, angry about being perceived as female, or not being “queer enough.” These are moments of discomfort and distress that arise when the pains of the social world penetrate my interior space. They are small wounds, just needling pinpricks, because I am at peace with my place in nature.

Like a Tomie, growing crookedly from a puddle of body parts like an outstretched cordycep, I am my own creature.

Smiling.

So, no. I don't think Tomie is non-binary, agender, or transgender. I don't think she's asexual, a lesbian, or any combination thereof. I don't think the details of her nude form are meant to convey anything in particular, either. Tomie is at her best when she's relishing in contradiction and ambiguity. Womanhood and girlhood are their own bundles of messy experiences, bright joys and strange terrors. There is a wealth of beauty in interrogating them.

But the less human Tomie becomes, the less recognizably female her anatomy appears, the more I relate to her. The closer I feel to her. The less of a monster she is to me.

Within her, I see a rupture. A possibility for change and adaptation.

“Aren't you tired of being nice?” she takes me by the hand to ask.

“Don't you want to become something else?”

That's why I can't stop thinking about Tomie, the happy cordycep I am, a creature built to survive the terrors that made me.

I think she would like that.

-

Thank you for such a through provoking examination of Jingi Ito's Tomie. You have proivded a new way of looking at this work. I am going to read this essay again because there is so much to absorb.

Add a comment: