Three More Stories Living Rent-free in My Head

I find myself thinking a lot about perception. Maybe that sounds too abstract. Too big to tackle. Too complicated a thing to unpack in a few words. All of this came to mind because of something my psychiatrist said to me recently.

“It was better that you didn't know what was going on,” she said, speaking of my child self. “You were busy taking care of your dogs and running around along the creek. If you were aware of what was happening, it would have broken you.”

The idea struck me cold. I nodded dumbly along at the screen, sitting in my apartment speaking to my psychiatrist via Google Meet. The sense of relative safety telehealth offered didn't keep my stomach from dropping. A wholly bodily experience of dread despite being reduced to two heads on a screen.

“I'm glad you believed what you had to believe. I would hate for you to have been broken by that. Because these things…they can kill you. And you're such a kind, gentle person. I would hate for that to have changed you.”

“Yeah,” I agreed in daze. “Absolutely.”

I never thought of myself as a gentle person, let alone a kind one. Softness and kindness were reserved for other, better people. Such things were held from me whenever people told me who I was. They said I was hard-headed. Cold. Mercenary in my disposition. My family was so helpless and hapless and in need of protection, and I just needed to stop being so dang mean to them.

I was the cruel one, you know. If you needed someone to say the harsh truths, you made me do it for you. Within reason, of course, because you couldn't trust me not to be a terror. That made it easy to let me fight your battles and to blame me for the fallout.

So what do you say to someone who calls you gentle and kind? What do you say when someone points out the lie that was your life and your perception of yourself? I don't know.

Yeah, I guess.

Okay, sure.

Then I'm someone different than who I thought I was.

But how do I know who's telling the truth? Me? My psychiatrist? My girlfriend? My mother?

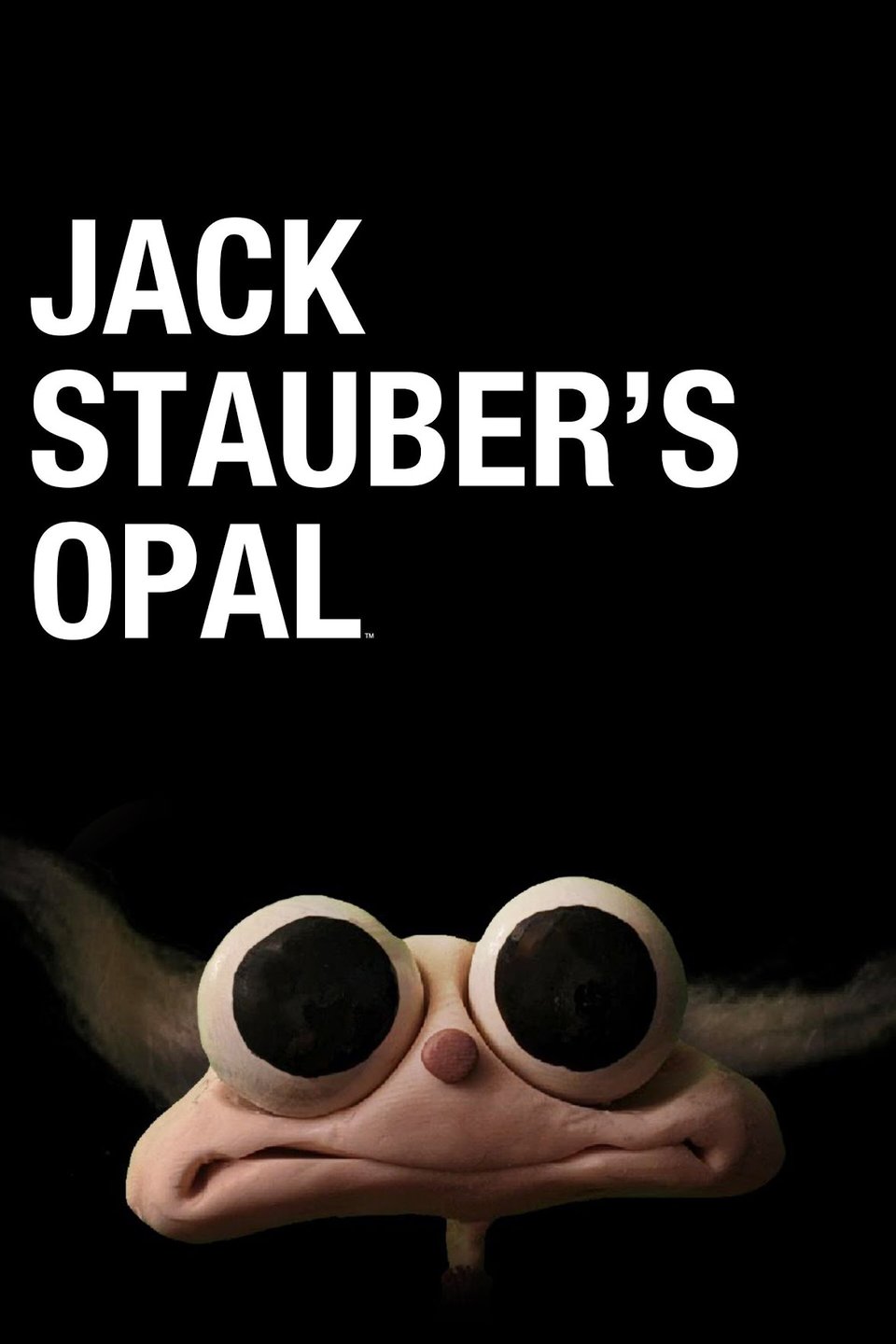

Anyway, have you seen Jack Stauber's OPAL?

So, 2024, huh?

I don't really have anything smart or pithy to say about last year. That sort of thing feels a bit beyond me. 2024 was pretty good to me in a lot of ways, despite everything happening all the time. I lost more than I thought I would. What I gained feels like it could balance that out. I guess we'll see.

Coming into 2024, I had no real expectations or resolutions to keep. I said I wanted to live more deliberately. To live slower, to move with more intention. I think I did an okay job of it, all things considered. My girlfriend, Melissa, called it a lost year. Too much was happening, not much got done. It felt like it moved too fast. I don't disagree. But I can't really complain about that.

In the last year, I had the opportunity to provide early reviews/blurb copy for some indie projects. This includes Billie Sainwood's debut poetry collection What was eaten was given, Mariah Darling and Eve Harm's splatter thriller novella Chasers, and the graphic novel Bar Veuve Noire by Jerna Van Vooren and Rado. It was a very cool experience and I appreciate that these creators trusted me with their work.

Because of these opportunities, I decided to open my inbox to other indie writers and artists looking for reviews. This led me to works like the compelling dark fantasy and science fiction collection No Castles by Costa Koutsoutis and the ambitious quarterly speculative fiction comics anthology Gravity Loop by Lichen Euchella and Ocean ET. It also gave me the chance to finally sit down with Sara Century's deeply personal horror film criticism zine SCREAM: An Overview of the First Six Films.

I've gotten through most of the requests that I felt that I could say something interesting about. Mostly on social media and in a pretty casual format, but every little bit counts when it comes to sharing art. I already have some stuff lined up to help get the word out about this year, and that's pretty cool.

2024 was the year Melissa and I got more into zines. We've always gone to local craft fairs for art and jewelry from local makers, but we made the effort to spend more time in/around independent publishing in our area. This led us to two afternoons spent at the Small Press Fair and the Miami Book Fair respectively, coming home with tote bags full of DIY comics and zines.

Lovingly drawn and stapled, pasted together and scanned. Beautiful, delicately folded sheets of glossy printer paper or harsh stacks of collage pages stitched together at the spine with ribbon. Pocket-sized magazines about rejected Tamagotchi designs and horror movie slashers, erotic encounters and alternative fashion. It's always exciting to put money in the hands of real people for tangible art objects, especially when they live just down the road from you in an amusing twist of fate.

2024 was the year I tumbled into love with yet another Claire Napier comic. (You may remember how highly I spoke of The Magic Necklace a while back.) This time it was the raunchy, riotous romantic comedy Wolf Story. I highly recommend it, as I do for all things Claire Napier. I finally picked up the first few volumes of the grotesque psychedelic nightmare Parasitic City by Ero-Guro master Shintaro Kago once they were available in English. While I can't say I loved reading them, per se, made ill by the staggering detail of impossible cityscapes and the contorted, distorted, eroticized figures pulled apart by the forces of their philosophically dense world, I'm so glad that I did.

I started, fell off, restarted, and fell off again of Berserk. I have some pointed thoughts and feelings, all of which are difficult to cast aside when I'm only a third of the way in and I know (through cultural osmosis) where we're headed. We'll meet again, Guts, just not yet. In a similar vein of dark fantasy, I became very obsessed with Vermis, a two-volume illustrated guide for a game that doesn't exist by the artist Plastiboo. These slim books hold some of the darkest, saddest, and weirdest designs I've seen. Each page feels oppressive in its construction, as if made of stone and covered in rot and mold. Vermis is a wound of a world that throbs with dread as the fictional player trudges through strange lands and stranger castles to confront unknown evils.

Rounding out this list of gnarly stuff, I spent most of the year thoroughly captivated by the work of Shin'ichi Sakamoto. I picked up DRCL: Midnight Children after oohing and awing over Sakamoto's gorgeous pages on social media and fell in love with it immediately. This is the first time I can say that Dracula (or vampires in general) truly unnerved me. Sakamoto takes the epistolary form of Bram Stoker's novel and turns it on its head, exploring it in a way that makes letters and journal entries feel exciting to parse.

Who these characters are, what their motivations are, who is telling the truth, what Dracula even is, none of it is clear. The story shifts and melts off the page, characters and perspectives taking on strange shapes as the narrative bends under the weight of the approaching otherworldly horror. Dracula is less a vampire and more of a virus, an idea that has metastasized and spread. Gorgeous, scary, and dripping with perverse desire, Sakamoto's art is nothing short of stunning.

Keeping the Sakamoto train running, I also picked up the multiple omnibuses of Innocent, the historical epic. This bloody, uncompromising story follows Charles-Henri Sanson. Sanson is the infamous executioner of 18th century Paris, a deeply conflicted and tragic figure whose family legacy puts him on a collision course with all the major players of the French Revolution. The line work is ethereal and gore-soaked, creating gorgeous tableaus of death and sex that leave me awestruck despite my squirming discomfort. Sakamoto just does not miss.

But all of that said, for all the stuff that I connected with over the last year, there are three pieces that have lived totally rent-free in my head. I have obsessed over them, talked about them, raved about them, and returned to them over and over to tease out exactly what made them so compelling to me.

So, let's talk about that.

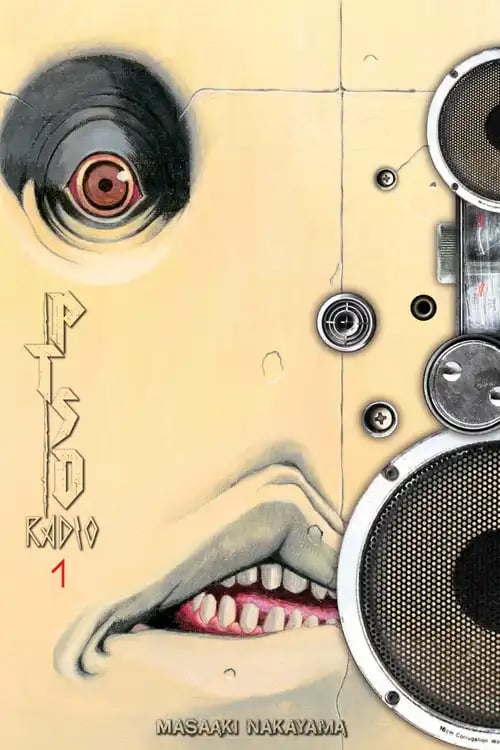

PTSD Radio by Masaaki Nakayama is the scariest anything I've ever read. It gave me nightmares. It made me scared to be alone in my apartment. It had me jumping at shadows and scurrying for the safety of brightly-lit rooms. Simply put, PTSD Radio ruined my life for approximately one week, and I'm grateful that I let it.

The unfinished horror manga series is composed of short, loosely connected vignettes. Each story is framed as a transmission, a random burst of human noise in the static. These vignettes weave threads across time and place like hair to bind the characters and locations together. They tie the disaffected modern city and the countryside with its old ways and gods, as hungry ghosts descend upon the world.

It's to do with the hair, you realize from the very first page. A young girl sits before her unkind grandmother as the frail woman cuts off all her hair. The grandmother says it must be done, now and twice more throughout the girl's life, for Ogushi, the one who pulls their hair so tightly. To earn his favor, and be spared his wrath, we must all make sacrifices for Ogushi. The hair is snatched by white hands on the train at night when the girl, now an adult, fails to heed her grandmother's warning. It's the hair in the interstitial illustrations between stories, a fine black curtain of hair falling over the faces of strange figures in the dark. Faces emerge from that dark to look at you as you turn the page. Eyes rising. Lips parting. Teeth protruding. All draped in long, black hair.

Even the book in your hands follows the will of Ogushi, it seems.

What PTSD Radio is, exactly, is hard to pin down. Over the course of the three fat omnibuses I eagerly devoured, Nakayama unspools a story of all-consuming dread. Vignettes follow the spread of Ogushi's curse as the angered god escapes his cult's remote site of worship. Some characters we know through repeated encounters and disparate moments flashing back and forth in time. Every story fragment, the transmissions of the titular PTSD Radio, speak to traumatic events in these people's lives, like snapshots of the unspeakable. They exist as random, shocking moments without resolution or catharsis, each horror suspended in time as you flip the page to the next.

Ogushi extends out into the world through rapacious crows and tendrils of black hair and grasping white hands to infect these moments. No one is spared from these encounters with the god, not even infants and children. Everything Ogushi touches twists and contorts and so do the people under his influence, hollowed out to accept the god inside them. The way Nakayama distorts limbs and faces is truly harrowing. Fields of black ink make voids of human eyes and teeth and hair as people stretch and elongate to fill space in ways they shouldn't.

There is no escape from Ogushi. The god is everywhere and on every page. He plays into real fears of being stalked, grabbed, or pushed in public spaces, turning mundane urban settings into minefields of unpredictable violence. In the home, he manifests as an impossible face peering through the bedroom window or a lover’s hollowed-out gaze watching you sleep. Even your screens aren't safe from the curse as spirits find the places you hide online. Slowly, as recurring characters put their own disjointed lives into the context of the cult and curse, a hazy plot begins to fall into place. Ogushi's curse transforms, mutates, and adapts as these characters -- and the reader -- adapts. The book and the curse it contains feel alive in that way, doing everything it can to keep you from getting comfortable or complacent.

As stated above, PTSD Radio is an unfinished series. The story cuts off rather abruptly at the end of the sixth volume due to Nakayama putting the series on an indefinite hiatus. Here is where we have to stop and address the two elephants entering the room. The first is that the last two volumes start to feel a bit mechanical. Nakayama begins filling out the truly unnerving logic of Ogushi and the world he operates within, while also falling into a rut of repetitive scares. There's only so many times a guy can see a scary woman looking at him through his top-floor window before it starts to lose its bite. Those bulb flashes of shocking lore are intriguing but the plodding vignettes they're sandwiched between dull their impact. It's unfortunate, really, because when Nakayama hits, he absolutely hits.

The second is that these later volumes feature autobiographical stories explaining the frequent hiatuses that troubled the manga's chapter release schedule. Or rather, strive to, then become documentation of Nakayama's paranormal experiences in a studio space he was renting during the production of the series. I'll try not to get into the weeds here, but Nakayama suffered a sudden debilitating illness and a series of strange occurrences in the studio. Everyone he told about this or witnessed it themselves had some kind of misfortune befall them or disappeared without a trace. And so the story itself, his own experiences and recounts of them, became a kind of curse.

A curse that he penciled into the book you have just been reading, to explain why the book was delayed and eventually suspended entirely.

To be completely frank, I kind of hate the inclusion of the autobiographical segments. I don't know Masaaki Nakayama or his life. He may believe this to be a factual account. He may not. He may have been a very ill man under a lot of stress who believed his suffering was caused by some paranormal malady. He may be telling a scary story inside his scary story. I don't know, will never know, and am not particularly motivated to find out. Something that weird would usually demands my attention, but it just doesn't work for me here.

What I do know is that these segments do little but slow down and confuse a story that was already beginning to lose steam. I don't know how to engage with them or what I should take away other than empathy for Nakayama. Beyond that, I feel like he told me he was cursed and so now I'm cursed because he told me about the curse, which has nothing to do with the content of the manga I've been reading.

And that just feels…weird. You know? Like I came this far and have no idea what to feel about any of it once I turn the last page. The autobiographical material comes out of nowhere, apologizes for its existence, and then informs me that there may be repercussions for that existence. If he truly believed that he was cursed and spread it through communication, putting it in his manga sucks to put it mildly. If he just wanted to punch up a meandering story with creepy supplemental material, I have to give him credit for trying. It's certainly a memorable attempt, even if it landed flat for me.

Don't take that as a black mark on the series. I hope Nakayama is doing well and free of whatever issues that throttled this book. At its best, PTSD Radio provides a uniquely terrifying reading experience that taps into palpable fears. If it stumbled toward the end of its short life, I can forgive it. I can never look at getting my hair cut the same way again and I have PTSD Radio to thank for that.

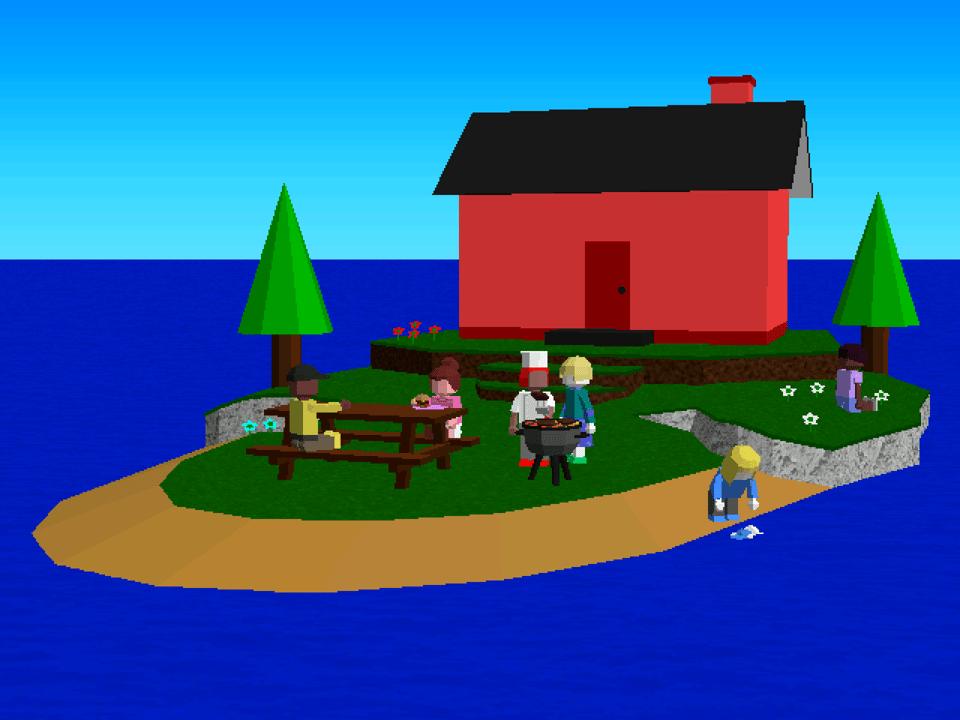

3D Workers Island is a digital horror story by Tony Domenico, creator of the experimental narrative project Good Sky and YouTube series Petscop. You don't so much play 3DWI as you experience it as a collection of Windows 98 desktop screenshots. It's the story of a screensaver of dubious origin released in the late 1990s. Well, to a point, anyway.

Nothing really happens in the screensaver. It features six blocky, faceless characters -- called workers in the screensaver’s readme.txt file -- on a pleasant green island. The six workers live together inside a red house and perform randomly generated activities. Watering flowers, mowing grass, grilling hamburgers. Sometimes sitting or standing and doing nothing. Their home has no windows or any sense of life within its walls. These workers are powered by something called advanced worker simulation, a complex system that creates randomized activities and events whenever the screensaver is on. All of these computations amount to rudimentary polygonal graphics and characters who wander around like tinker toys. Nothing ever really happens.

That can't possibly be scary, you're probably thinking. You're right. It shouldn't be, but Domenico understands what makes digital spaces scary in a way that deeply unsettles me. 3DWI is about people rather than pixels. The small but dedicated user base that grew around the screensaver is the primary subject we interrogate throughout the story. Fan shrines, forum posts, and AOL Instant Messenger chat logs tease out the discourses surrounding 3DWI. Some engage with it as a fun curiosity, others a peculiar fascination that compels them to install it on multiple computers throughout their homes. This is very much the case of Pat Lawler, or PLawer, the fan site administrator who runs the screensaver in every room, all day long. Users profess their boredom with the aimless characters or confusion about the fandom, unable to see the meaning everyone else sees. Factions develop on the forum between the administrator and a rebellious subset of users who engage in conspiracy about the true nature of the screensaver.

In both its text and presentation, 3DWI is a mirror that reflects what you choose to see. It can be a curiosity, an escape, an obsession, and a fun distraction. For dissenting forum users, it's a cry for help. These users see the young worker Amber as a victim of violence perpetrated by the adults, specifically her perceived mother Pat. The mother who shares a name with the website administrator, Pat Lawler. They collect their screenshots, theories, and firsthand accounts on a rivaling website. Amber is forced to perform labor until she grows red and distorted, a dehumanized lump of pixels. She whispers to users for help and sometimes screams in pain. Photographs of a tortured child wearing Amber's pink outfit appear at night but only to those who are willing to see. Photographs of children, real children, flesh and not pixels, in pain and distress.

And that's all anyone can do. To see Amber. To watch. To bear witness to her suffering. To document her pain as the public-facing community scrubs the evidence from their webpages and forums. Because Amber isn't real. The children in the photos aren't real. These are just chunky pixels on a screen where nothing really happens.

But what if the screen is not a mirror and instead a window? Through looking, what if pixels become flesh? What if our gaze could create alchemical miracles in cathode ray tubes, or capture something that was never meant to be seen? What if Amber can be made real if we watch long enough?

The beauty, the terror, of 3DWI is that there is no ending or catharsis to be found. You're free to believe what you want. This could be the story of impressionable or unwell people looking for meaning wherever their gaze settled. This could be the story of a fandom that imploded due to overbearing forum moderation and the gorehound tendencies of early internet edgelords. This could be the story of what happens when mirrors become windows and screens show us things we want to hide from. This could be the story of a ghost trapped inside a machine, an imprint of violence that repeats whenever your computer is idle.

Until you see it, finally, for yourself.

Broadly, I think what 3DWI gets at two ideas: what it means to be a bystander and what it means to be a witness. You can easily dismiss the things that happen in the screensaver as random and meaningless events, the same as you can dismiss the innocuous comments of some of the forum regulars. But if people expressing concern for a child character upsets others so much, you have to ask why, you know? Why does the concern for a child, or even the presence of that child in the screensaver, bring out such hostility? The sharply drawn parallels between Pat the character and Pat the administrator cast her motives in suspicion and bring Amber more into reality than any forum revolt. How many real children does this happen to? How many suffering children do we turn away from because it simply isn't our business? It's a family matter, and what happens behind closed doors is the domain of the mother or father, as if ordained by God.

On the other hand, if you are witness to such suffering, what is your obligation? Do you act? How do you act? To bear witness to suffering is a powerful act of solidarity with and love for another person. To acknowledge their pain and live with it inside you, sharing it, honoring it, can be beautiful. But what does it mean if you can't, or won't, intervene to stop their suffering? What crimes are these users documenting? What suffering are they cataloging? To whom can their concerns be addressed? How can they help someone suffering in silence if Amber can't be reached, if Pat can't be stopped?

What does suffering amount to when there's no one to save? Worse yet, what do you do with that suffering when you're too powerless in your own life to save someone else?

3DWI left me with questions and questions and questions and no answers. I think I like it better that way. The questions live on in my brain, turning over and taking new shape each time I revisit the work. I still don't know exactly what I think happened in this story. I'll let you know when I do.

Jack Stauber's OPAL is a twelve-minute musical claymation short film that premiered on October 31st, 2020 on Adult Swim. Jack Stauber is an artist, musician, animator, and filmmaker who rose to internet virality with his surreal animations and synth-pop music. If you've been around on the internet since 2020, you've likely encountered Stauber's peculiar mix of lo-fi VHS aesthetics, often disturbing animations, upbeat pop sounds, and sad, strange lyrical content.

What you need to understand about OPAL is that it's a documentary. When I say OPAL is a documentary, I mean that it is the most empathetic and organically designed portrayal of child abuse and neglect that I've ever encountered. Stauber, through a stuttering, breathing, heaving blend of stop-motion, claymation, 3D animation, and live-action footage, has tapped into experiences I've physically lived that it's almost violating.

To be seen by OPAL is to be seen as a child, by the child I was, and acknowledged by another adult for what that seeing means. To be seen is to be loved in OPAL. That is such a small, simple thing, yet it rattles me to my core.

You have to watch OPAL to experience it for yourself. It tells the story of the titular Opal, a young girl with a seemingly perfect life. Her parents and grandfather see her and believe in her. They each have deep, black, loving eyes, filled to the brim and spilling over with her reflection. But when she hears cries coming from the attic of the creaky old house across the street, Opal is overcome by the need to help. To reach out to this crying, wailing, person, whoever they are. Her parents forbid Opal from looking at it, but she must. She sneaks out of her perfect little house and steals away to the forbidden house, a dirty, decrepit inverse of her comfortable home.

There, Opal meets the perverted version of her family. A sickly grandfather who stinks of cigarettes, rotting in the armchair before the too-loud television. A preening father focused on his appearance and appraisal by others, mired in the self-loathing he uses to deflect blame and gain sympathy. A mother lost in a daze of wine and pills, locked in her decaying bedroom and muttering about her failures and enemies and the goodness that will come if she just waits and sits very, very still.

Opal must face these three monsters to make her way to the attic. She climbs the floors of the house, meeting and escaping the adults to make her way to the room that calls to her. There, running from the wheezing grandfather, crying father, and shrieking mother, Opal's journey comes to a harrowing conclusion in that room that leaves me with a pit In my stomach.

I will not say what the ending is. You should watch this for yourself.

Stauber's score consists of bops and ear worms that defy all narrative tension. The grandfather's and father's songs, Easy to Breathe and Mirror Man respectively, are fun and grimly funny. They explore each man's cartoonish narcissism and keep the dread it bay until the mother's song, Virtuous Cycle. This slow, music box tune portrays the realities of child neglect, as the mother asks for a little girl to care for her in this withered, hopeless state. The mix of different mediums and animation styles make Opal's world feel small, dark, and oppressive. Everything is worn and dirty, textured and creased, the spaces and characters alike. It creates a strange sense of dissonance, where everything feels real and heavy yet untethered in space. The rooms are difficult to parse with characters who shift from clay to live action within seconds. It's a nightmare to experience.

Where Stauber catches me off-guard is in his portrayal of Opal's subjectivity. He renders the different faces and facets of child abuse the way it appears to a child in the moment. The hypocrisy and contradictions that come across as completely absurd to the adult viewer are deadly serious to the child. The things that make no sense are truths and the power held by adults is absolute. We see the adults as pathetic husks, self-absorbed, deluded, lying to Opal and themselves to cope with their failures. Generations of adults made from abused children, living in cycles of pain and neglect under one roof. But if you've ever been in Opal's position, you know what it's like to hear these things, to believe them, to take them as reality.

Each of the adults say things I've heard from my own parents over and over for decades, from my earliest memories on. The grandfather's “It's evil to help people.” The father's “You know how this makes me feel.” The mother's “We don't live, we survive.”

You're just as helpless as I am.

Why are you always so angry at me?

I have never in my life experienced the real cruelties I've been subject to, word for word, spoken in a piece of art or media. That is terrifying to me, and it makes me so sad that it's common enough to make a cartoon about. But for all the horror OPAL pulls out of me, I am truly moved by how Stauber treats the character. She is deeply empathetic, moved to care for others in distress no matter how she is forced to care for the adults. It is a pure, innocent, and beautiful thing. She wants to see others and be seen by them, to love and be loved. To help people.

And, most importantly, to help herself and see herself as someone worth love and care and rescue. The story is not forgiving the adults but forgiving the self for what the adults did to you and what you couldn't keep from happening. Stauber gets that, I think. He gets that work. I feel seen by OPAL in a way that I never thought possible.

It makes me think about what my psychiatrist said before. About not letting knowledge break you. I think I get what she was talking about now.

I wish we didn't have to make art like this anymore. I wish people didn't feel so seen by this. But I am glad that it exists, and in such a loving way, despite the horrors that made it possible.

Add a comment: