Three Books About Destroying a Body

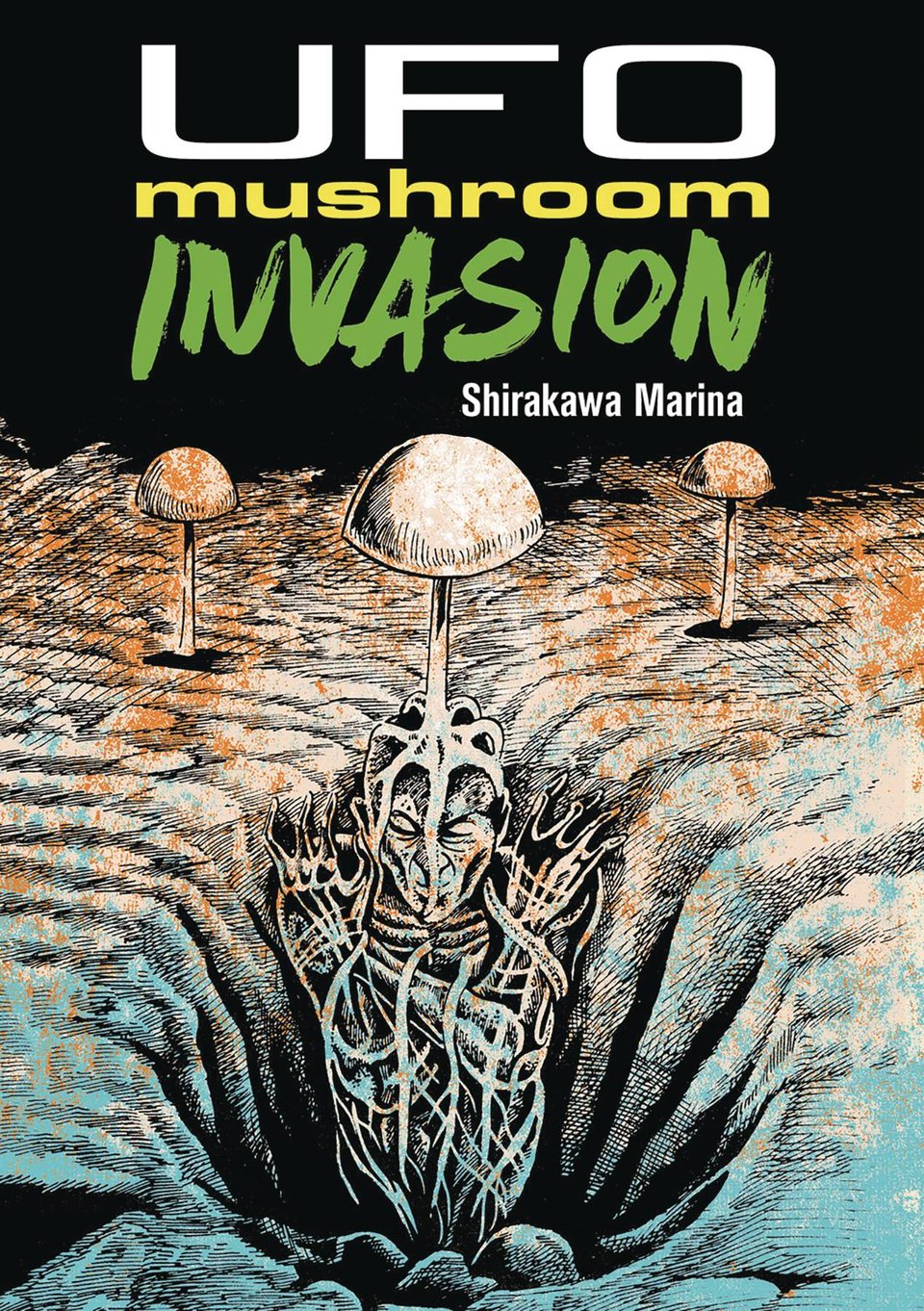

In the final pages of Shirakawa Marina's 1976 manga UFO Mushroom Invasion, humanity's domination of the natural world is coming to a close. Fungal spores from a crashed alien vessel have entered the human body to plant networks of mycelium. These networks of delicate fibers attach to organs, bones, flesh, turning the body into a host for new life. Skin darkens as limbs contort into new shapes, faces shrinking behind the web of thick, corded mycelium that engulfs their skulls.

A little boy named Aoki watches in horror as humanity slowly dies. The dessicated remains of his parents and baby sister are animated by the fungal parasites bursting out of their backs. Mushrooms reach up toward the rain for nourishment. Bodies lurch forward through the pitch rainy night, moving to the next location to spread more spores, more mycelium. Those who remained behind abandon any pretense of humanity to take root in the soil. Their skulls open into the fanning mushroom caps, their torsos reduced to bulbous, cancerous-looking stalks.

Aoki, his lungs filled with spores, can only wait for the mycelium to spread through his organs. He sits on a playground swing. His tears are lost in the rain. Perhaps, he thinks aloud, left only with his thoughts, it's better this way. Without people, there will be no war, no pollution. By morning, he will be gone.

The earth does not weep for Aoki, but we do.

I don't know what it says about me that I've been reading a lot of body horror lately. Nothing particularly good, I think. That might be too strong a way to phrase such a sentiment, but it's how I've been feeling. It's…uneasy. Unsure. Body horror in and of itself is a neutral storytelling device, of course. It exists to express contextual tensions, anxieties, desires, and discourses around the body.

Well, the body and the political subject. Because we're never simply bodies. We're our skin colors, our genders, our disabilities. Thinness or fatness. Full hair or thinning. Good teeth and nice skin or weak bites and weathered flesh. Whether we can produce children and how and to whose standard. What we do to bodies in our stories can tell us a lot about how we think of bodies in our everyday lives.

And I've been reading a lot of body horror. And so I've been thinking about what we do to bodies on screens. I don't have to do much to see the horrors enacted on human bodies. That kind of bothers me. I think it should.

Growing up a tween on the “Wild West” of the old English-speaking internet meant that I was exposed to a great deal of horror from a young age. Grainy videos from the scenes of car accidents, compressed photos of animal slaughter, and the sterile violence of prison execution footage, all when I was far too young to understand what I was seeing. It used to be a rite of passage, the way it was explained back then. I'm told it still is for some. Recorded suicides and murders livestreamed on social media get shared around amid unsavory company.

I've even had men get mad at me on the internet and send me photos of human remains over…I don't actually remember, now that I think about it. Just because they could, I guess.

That sort of stuff makes the things that we do to bodies feel like entertainment. It trivializes the extremities of human experience. Human suffering. I know that the shock of real life gore made me curious about other taboo subject matter as a teenager with internet, cable television, and insomnia. While my parents slept, I would stay up until dawn watching whatever upsetting movies I could get my hands on. Simulated gore and unsimulated sex. Realistic torture and pretend cannibalism. Actors pretending to perform or to enjoy performing depraved acts.

Somehow, perhaps appropriately for my age, Adrian Lyne's 1997 adaptation of Lolita traumatized me more than Takashi Miike's Visitor Q or Ruggero Deodato's Cannibal Holocaust. The gauntlet of disturbing material I (both willingly and unwillingly) exposed myself to in my youth helped me develop a callus for it. But with that callus came the resolve necessary for appreciation and critical engagement. I've come to see the extremes of human expression and physical suffering as a means to challenge, subvert, and deepen our understanding of ourselves.

So then why do I find myself thinking about body horror so much if I'm no longer sure what that says about me?

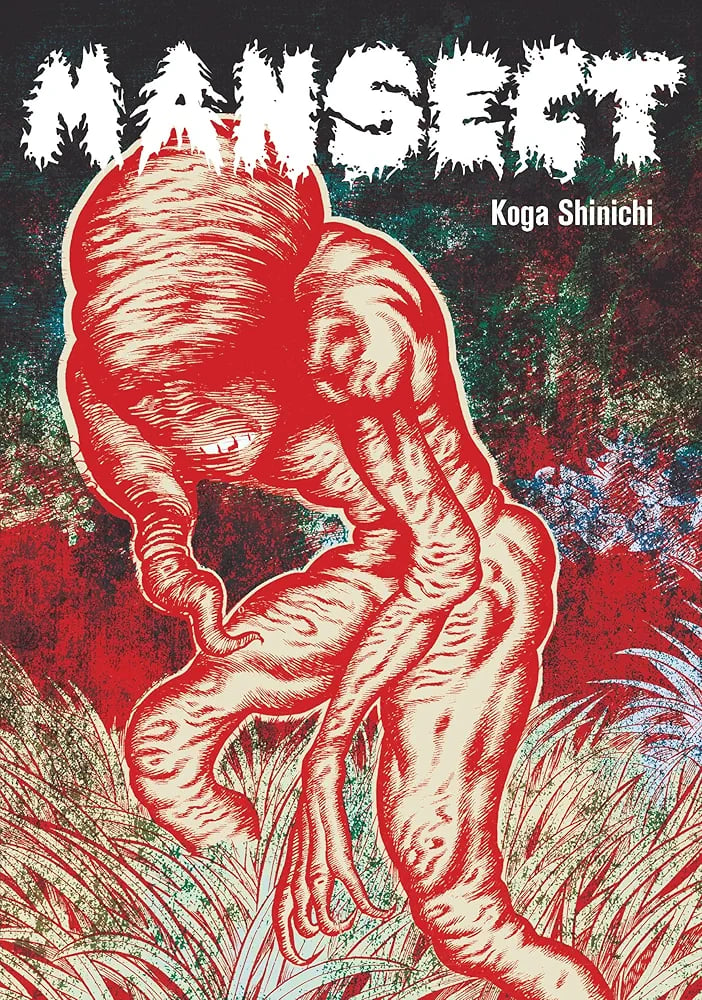

Koga Shinichi's 1975 manga Mansect is a mean little text. Its sprawling, anthological narrative contemplates humanity's tenuous place in nature through the lens of body horror and the uneasiness of the home. The body is the site of radical transformation as social tensions give way to new extremes.

While not the protagonist, per se, Hideo is the story's catalyst and throughline. He is an aimless, reclusive young man. Following the death of his mother, Hideo retreats into misanthropic delusion. He locks himself inside his mother's home and spends all his time with his growing collection of insects, cut off from neighbors and other young people. Without her, he has nothing and no will to live. His mother's voice, perhaps real, perhaps imagined, haunts their home at night. As her spirit urges him to move on, to become self-sufficient, Hideo wishes to die and be reborn as one of his beautiful insects.

A strange wound appears in his leg to grant his wish. The gash begins to spew silk threads, signs of a disease no doctor can diagnose. It spreads like an infection as his body softens and dissolves. Soon the silk entombs Hideo in a chrysalis but a house fire forces him to emerge too early. Hideo is rendered a goopy, malformed thing, a pupa unable to become a moth.

As he stumbles to safety, the biological malady within him spreads throughout his rural village. The townspeople change one by one. Children become diseased and die. Families are torn apart by horrific transformations. Beyond the village, doctors across Japan puzzle as people take on strange, painful new forms. This degradation of the human body has become endemic.

Hideo continues to metamorphize, trapping and consuming anyone who happens upon him. The loathing that motivated him to cut himself off from the world manifests as a delight in consumption. Cannibalism changes his form again and again, his body's plasticity yielding strange horrors until he is reduced to an infant state. He latches onto throats the way an infant takes to the breast to bleed his hosts dry. Once more, Hideo can't survive without a mother to maintain him, sustain him, and so he finally dies.

The joke tells itself: A man would rather become a bug than go to therapy. I tend to see it in a more complicated light. No matter how important we are, how high-minded our pursuits, if we aren't in dialogue with the natural world, it will decide for us when our time is up. Hideo used insects as a cover for a selfish, parasitic nature, and dared ask them to accept him as one upon rebirth.

They said no.

How wretched must we be to be denied by insects?

As an adult, I think about violence a lot.

Being an American means sloshing around in a vat of the stuff from birth. There's the real violence, sure, the kind that begins in the home and leaks out into the streets. Or the kind that stems from generations of poverty, disenfranchisement, and incarceration. Slow, quiet deaths due to social neglect and government malfeasance. Medical clinic bombings. School shootings. Mall shootings. Shootings at churches and temples. Camps at the border. Even our car culture is a form of violence, with tank-like vehicles so hulking that they liquefy pedestrians in the crosswalk and demolish smaller cars on the road.

For all of that aforementioned horror, sometimes I think the imagined violence is the stuff that really messes with your head. It's the sense of being stalked at the grocery store because you've seen too many TikToks about human trafficking schemes. The true crime podcast brainrot that heightens existing alienation and paranoia to a fever pitch. Stranger danger on a national scale. I don't think we get the Purge film franchise without a deeply sown fear of our neighbors weighing down all of our psyches.

However, as both an adult and an American citizen, it is my privilege to see what horrors my nation and its proxies commit from the safety of a warm bed and a screen. Not just the home computer screen of my misspent youth but the family television in the years after. That's how I understood the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, through the TV. It was so soft and fuzzy, so far away. I would see the bombs and the shelling and the tanks in pixels, but it never touched me. It scared me because I was a teenager and I was afraid of war, but I was never burnt by it. Scarred by it. Never tasted dirt or gun powder or white phosphorus.

I could look away when I wanted to because it was just on TV and I have agency as an American.

Nearly two years of the live-streamed genocide in Gaza and the West Bank has given me a taste of a hell that I otherwise can't fathom. Articles written on and photos taken of survivors from other widespread murder campaigns never registered with the immediacy of footage from those being bombed as they are being bombed. I didn't even seek these images and videos out. They're everywhere, everyday. A million images and videos of a million bodies and souls. Sometimes it's the shakyl iPhone videos of people documenting the day's aid site massacre or tent fire. Others, it's Israeli drone footage of body parts strewn across the street and blood clumping in sand.

These are more than pixels. More than bodies. They are real, breathing, thinking, feeling, human beings. Alive in one moment and gone the next.

I don't know what seeing that is doing to me. I don't really want to pontificate on what it means, either, because this goes so far beyond me. I feel what I feel because I have no choice but to feel it. My tax dollars pay for the bombs that shred children into pieces and turn schools into craters. My tax dollars starve newborns to death and slowly kill their parents through disease, injury, and hunger. I feel this because I know this, and so I must live with that inside of me. I must.

I mustn't look away.

I'm no longer a child and I mustn't look away.

All I know for sure, if I know anything for sure, is that I am dazed with grief whenever I look at it. The well in my stomach deepens. My fingers are heavy and moving like iron rods as they go to type out another “I'm so so sorry, my friend, I pray you and your family stay safe” to an online friend in Gaza. People like Adham (a very kind and thoughtful young lawyer) and Najwa (a mom with a chronic illness and a sweet nature), who I met on social media over the last year. Dragging my fingers uselessly across the digital keyboard on my phone, I try to help raise survival funds for them and their families. I can neither confirm nor deny the existence of a god, but if he does exist I am furious with him.

Adham looks thinner and thinner in his latest photos. Words fail me. Sometimes he disappears for a few days at a time; when I finally hear from him, he has nothing but horror to tell me about. I feel terrible for asking, but asking and sending my prayers and sending monetary support when I have it to spare is what I can do from my side of the screen. I wish for a different world, one where we could chat online about things that don't matter. Books or work or holidays at the beach. Sometimes I stop hearing from people altogether. I hope their phone just got stolen or they were IP banned from Instagram or Bluesky. The encouraging emojis I use in lieu of anything more than cold comfort serve as an epitaph as I close the app on my phone.

And so I've been reading body horror.

But what does that say about me?

I tend to think it's my way of grieving. As when speaking of the genre itself, I mean to talk about grief with just as much neutrality. I don't believe that art needs to achieve a specific material goal, especially not an educational or therapeutic one. A story can do whatever it wants. Who am I to say otherwise? I have a newsletter and a lot of opinions. Whatever meaning I manage to cleave from the text and its mishmash of intent and message is nobody's problem but mine.

Yet body horror feels like a welcoming space to exist for a while. The nightmares that befall the flesh and spirit end once I close the book. They don't follow me across screens and platforms. Their terrors gives me room to think and dream about the extremities of human experience without having to subject someone to such violation. The horror allows me to empathize with the body and the universes contained within it, and to remind myself why it matters to still care about violence on screens.

To grieve, to weep, to be moved by images.

By bodies.

And sometimes it's just fun to destroy them.

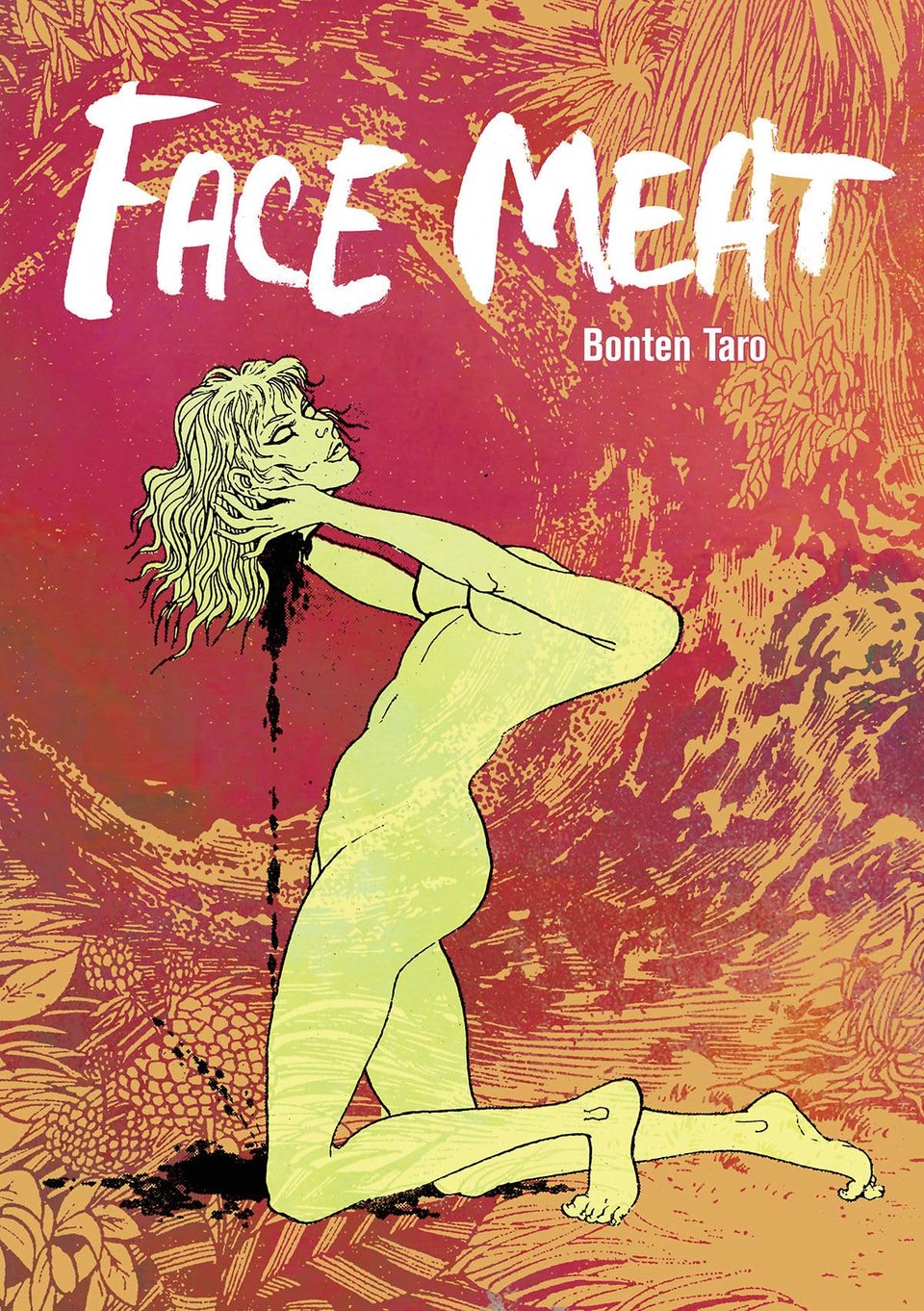

The closing panel of Bonten Taro's 1967 comic Poisonous Moth gets stuck in my head. Taken on its own, it doesn't really tell you anything. Two snake-like caterpillars rot in puddles of blood and hair on an empty white plane. Their skull-like faces are obscured from the viewer by seeping black ooze, a bulging eye barely visible in one of the sunken heads. Above them flutters a moth with strange proportions. The oddly human-like face, what should be the back of the insect's head, presents like a pair of beady eyes and a smiling mouth.

The two dead caterpillars are Reizaburo and Kiku, the younger cuckolding brother and cheating wife of the old royal guard they conspired to poison. As his body rotted and fell apart, the old man discovered that he was being turned into an ugly little caterpillar. The old man took his revenge on his brother and wife, transforming into a poisonous insect to infect them with his blight. While they died, wandering outside to shrivel up without water or food, the old man escaped as a moth.

Bonten Taro occupies a weird place in adult horror manga. Known very broadly in popular culture as a tattoo artist throughout the 1970s, Taro published a number of trashy comics in men's erotic magazines during the 1960s. His work is concerned with Gothic traditions: decay, obsession, monstrosity, madness, and perverse desires. The men are ravenous. The women are beautiful and in peril. The monsters are the stuff of pulp comics and old Hollywood horror pictures. It's horny, yes, but it's also mean as hell.

Taro's style pulses with crass libidinal energies. Whether he's cartooning the inviting curves of a busty woman or the sharp features of a grinning serial killer, there's a real menace in every pen stroke. Spaces rendered in dark shadow portray a heavy, oppressive mood while characters within those spaces are rarely static. They feel like they're moving, or about to move. Blurs of kinetic energy whose momentum is trapped by gestural lines, if only for that image. Notably, the women feel as if they're dancing or swimming or falling; their sensuous bodies are forever at risk of tipping over into vulnerable configurations. The men often are wound up like predators, animals about to pounce on their prey and carry them away in their teeth.

Poisonous Moth was the first story in the 2024 collection Face Meat that really resonated with me. There are others that I liked quite a bit, but there's just something about this one. Two brothers, both members of the emperor's royal guard, are in love with the same woman. The younger brother and wife scheme to not only kill the elder brother but use supernatural means to fully dehumanize him. Believing that he's dying from an unknown sickness, the elder brother begins to decompose. His limbs rot away and his features retreat into his skull, teeth and hair falling out. Reizaburo cuckolds the elder brother with a vicious zeal, pouring the last of the poison down his throat before having sex with Kiku in front of him.

In the end, the elder brother gets his revenge. Himself little more than a wriggling worm, he spits his venom into their water to damn them to the same fate. Vengeance frees him. Although he's lost his humanity to the cuckolding plot, his righteous fury has transformed him into a moth. Kiku and Reizaburo die horribly as caterpillars but he overcomes their machinations with an impossible smile on his inhuman face.

This comic is a perfect little summation of Face Meat as a collected volume. For me, it was helpful in understanding the rest of Taro's work as presented. It finds the glee in this horrid revenge and ensuing death. I can't say I've seen that very often in other works of a similar subject matter in recent years. That was more surprising than any rotting corpse.

To Taro, the body appears as a playground of both erotic delight and impish destruction. Historical settings offer bloody clashes between humans and folkloric creatures, with the presence of spirits carrying forward to rupture the modern day. Beheadings, disfigurement, and dismemberment are such common occurrences that they began to wash over me. Infants are chopped to bits by spirits or eaten whole by their monstrous siblings. Murderers hack the heads off dug up corpses, their bodies disregarded and disrobed, to wear their faces on late-night television. Even your face isn't safe, your body merely a tool for visual pleasure and grotesque expression.

Men don't so much assault women as they devour them, with rape becoming an act of consumption that feels more like cannibalism than sex. Because these are sexy comics in sexy magazines, the women are plastic and submissive. Their heads lull back in ecstatic pleasure even as “No” dies on their lips. Behind that “No” is a woman who hasn't let herself say “Yes.” The violence we do see isn't particularly gory, often hard to understand amid commingling smears of blood and shadow. But it is sexually-charged in its determination to show off perky tits and arched backs, blowing past any pretense of horror to revel in pure erotic spectacle.

At some point, it's all so nasty that I just have to laugh. The stories sprint through lurid scenes and subject matter so quickly, and end so abruptly, that it's hard to take seriously. Taro's sharp, scratchy linework and brooding chiaroscuro are delightful to explore, lending a visual gravitas to thin plots and even thinner dialogue. The craft underpinning this impish approach to Gothic themes and titillation make them far more enjoyable than they might otherwise be in the hands of another artist.

Even as I laugh, unable to find offense in what was boundary-pushing stuff in 1960s Japan, I do have to wonder what my reading amounts to. The comics are mean-spirited but also often very playful. They feel like an exercise in mischief-making and transgression of accepted taste. Taro's publicly affirmed right-wing politics make a home in the text, yet the tension between productive society and libidinal desires is present throughout the collection.

Taro is a rebellious and counter-cultural figure, once a kamikaze pilot who narrowly escaped death, then a gangster, then a musician, then a tattoo artist. Freedom from restraint manifests as depravity performed by male actors, the only subjects granted true sovereignty. This, in and of itself, presents a kind of paradoxical transgression, rendering fantasies of brutality that inevitably engage in socially acceptable forms of power. Men are actors while women are enacted upon. Prominently disabled or disfigured characters are presented as monstrous, lecherous, and criminal. Being cucked is a fate worse than death.

But to say that feels…simplistic.

That deeply conservative verve is certainly running through these comics, but they are still trashy comics in dirty magazines. They are crass and horny and fast-paced by design. They are often quite silly and present themselves with a wink and a nod at the audience. They appeal to your Id, my Id, by indulging in striking erotic imagery, then getting the hell out. I can't say a comic in the collection really overstayed its welcome for me. It's not bad material elevated by good craftsmanship; it's just good dirty comics. It's transgressive enough to scratch the itch but ultimately feels mischievous rather than misanthropic.

Taro destroys the body with glee rather than overt malice. The body is merely a tool for storytelling, its flesh a vehicle for expression. If the body must be good and productive to be valued by society, then Taro asserts that it will be controlled by primal desires. It will be corrupted by supernatural forces or hacked to bits by a madman's ax. People will drink and be lecherous. Yeah, there's pearl-clutching anti-communism, but it's next to stories where sexy fashionable men sell their souls to sleep with hot women or become grinning snake-like monsters in nice suits. You can't loathe or pity such characters.

There is precarity in the human body and the social systems that ritualize it. Life is often violent, often cruel, often tragic. And sometimes you just have to look at it and laugh.

Right now, I think I need that laugh.

-

This was very beautifully written. I wish I had better words to describe how much I enjoyed reading this, and how much I saw so much of my own fears and feelings reflected back at me. Thank you for loving and fighting for your Palestinian friends in whatever way you can. I hope one day you all can talk about nothing important, as everyone should be able to.

Also, I very much loved every summary you gave for each story. I always loved body horror due to it being transformative in some way, and I probably romanticize it more than I should. I will definitely be reading Mansect soon. Wanting to become an insect out of grief and fear and fly away is very relatable, and I love consequences.

Hope I don't sound nuts. This newsletter just resonated with me a lot. It was sad and thoughtful and wonderful.

-

Cannot wait to find and devour UFO Mushroom Invasion, being a big fan of anything cordyceps-related. Thank you for sharing these works with us.

I wonder what you'd think of the works of Shintaro Kago. Body horror on a factory-farm/industrial scale, that often takes my breath away to witness.

As one of the first folks to have received the honor of nonbinary affirmation surgery, years before it received that name, I too have had a long, long relationship with body horror as it's depicted in comics and films. I'm grateful Microcosm Publishing was up for publishing the little informational zine I wrote at last, "Bigenital Revolution," where I warned at one point, the process of such a surgery is to LIVE a personal version of body horror, with one's self as the canvas. While it was BEYOND worth it for me, like I said in the book, "body horror hits different when the gore is part of YOU."

But, I don't mean to shift the discussion to Trans Affirming Surgery As Body Horror Allegory. Merely a recommendation, if you choose to check it (or Kago's works) out.

Also: thank you for the work you're putting in to help anyone in Gaza. As the parable of the youngster saving beached starfish while an old man jeers about the uselessness of their efforts would say, "Well, I sure made a difference to that one."

So. Just a fellow soul in this ancient fishbowl, swimming by to say thank you, and that I'm proud of you. Sparkling through a world that makes it so easy to be eaten alive by despair is no easy feat.

Add a comment: