This Story Is (Not) Yours

The sun sets so early in December

November 2023 marks a full decade since my first book came out. That's strange to think about. I don't really believe in celebrating “book birthdays.” It feels performative to me in ways that are hard to pin down, marking anniversaries for things that have long since left your mind and consciousness.

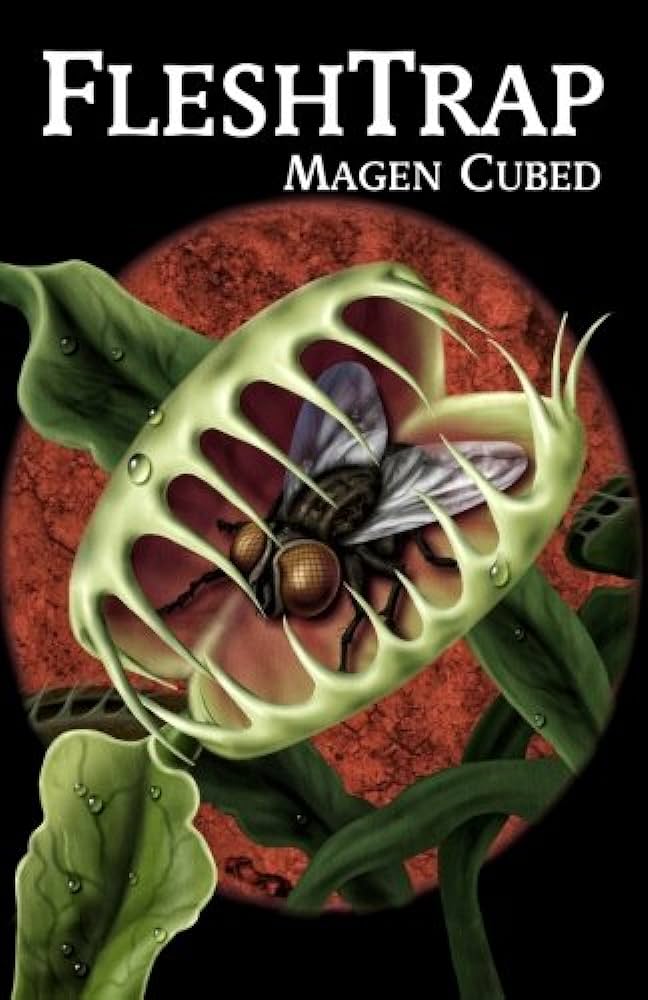

My book, my “debut,” Fleshtrap, was a psychological horror novel. A slow, dreamy, nasty little thing. It was about a man who couldn't sleep because he was haunted by terrors each night and in his waking hours. His mind spilled over with the hallucinatory crimes of his long-dead father, presented as an ever-present corpse with a dripping meat face, having been murdered by his step-mother for the abuse of his step-sister. The book was a brutal and deeply personal treatise on trauma and what happens to bystanders of other people's abuse. Those in the periphery of someone else's trauma, living in the same house, sharing blood with the perpetrator. The marks left behind that can't quite be named.

That's what I always told myself, at least.

It was very much of its time and place. I was in my 20s when I wrote it, back in the early 2010s, and it was appropriately edgy as such. There are things that I would do differently if I wrote the book today. Sentiments softened, dialogue refined. Ideas and themes given the space to breathe a little more. As it stands, in the shape that it's in, the book is a lean, mean package that desperately screams its content to the reader to make its intent known.

The book can't be read anymore. It doesn't exist. It's hard to say to what extent it really existed at all, having sold a few hundred copies in its lifetime before falling out of print. The publisher shuttered a few years ago, which I found out about in a social media post. That's how these things usually go.

Today, a few copies are in circulation at thrift stores and secondhand shops. I put several copies of the book into circulation myself. Sometimes, a copy will pop up on eBay or a used book repository. If you look hard enough, you might find it.

Or not.

It's important that it doesn't exist anymore. Important to me, anyway. It took me a long time to understand why.

The moon is bright and my heart is black

I have a tenuous relationship with fiction. Especially these days. That sounds strange, I’m sure. I write fiction. I enjoy fiction. I think about fiction. I think about other people's thoughts on fiction. It isn't so much the stories themselves as their function that trips me up.

Over the years, I’ve struggled with where to focus my writing. I flitted back and forth between fiction and criticism, talking about movies, television, and comics for outlets like Women Write About Comics, the now defunct Ms En Scene, the equally defunct Queership, and even my own short-lived podcast. There were other small sites I wrote for, little free blogs and trashy news sites and such. They are all long, long gone by now.

Now I have my newsletter to talk about the things that I like. It feels good to me now, comfortable and natural. It didn't always. Talking about other people's work often felt like a distraction from my own, especially given how slowly I put out new books and the considerable time between releases. At time of writing, I haven't put anything out since the two short stories I released in February 2022. There won't be anything coming out for the foreseeable future, either. It is what it is.

I told myself it was a misuse of my time to talk about art when I could be making my own. It isn't entirely untrue. Unprincipled, shallow fluff pieces, reviews, and the occasional bit of gossip wasn't a productive use of my time or energy. That was entirely a skills issue, as I'm soberly aware of now. I wish I had been more dedicated to it back then instead of abandoning critical writing, in whatever state my craft was in at the time.

Some people have been very kind in extending opportunities to write for them over the years. It feels just a little embarrassing to have shied away from the encouragement. The fact that my writing was thin and uninformed was the justification I used to explain away the fact that I was scared of having more to say in a review than my own work.

Perhaps if I had been steadier on my feet back then, I could have made something of myself in these spaces. I understand now that I'm better served as a writer to hone these skills, more prepared to craft art that is in conversation with its surrounding context. But that's the rub, you know? The question still creeps up at odd hours, in the mornings before I sign in at my day job, or when I find myself dividing my lunch hour between fiction and non-fiction.

Should I write my own story, or write about someone else's?

I only have so many hours in the week. Month. Year. Shouldn't I be working on my book? What do I even have to say about art that isn't hopelessly self-reflective? An essay about myself more than the work I’m engaging with? Shouldn't I just tell the story I want to tell, with the tools - my hands, my mouth, the ideas that pass between them - at my disposal?

It's always a conversation in an empty room, between myself and I.

“I’m only good at one thing,” I would tell myself.

“You really don't even have anything else to say,” I would tell myself.

“Just work on the next book.”

Truth, I find, is harder to deal with in fiction.

Guess it's time to write about Evangelion again or whatever.

Promise me you'll always remember

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to the conclusion that art should be a wholly selfish endeavor. If you do contract work and sell art to make a living, more power to you, man, but it simply could not be me. I spend eight hours a day writing marketing copy I don't care about already. The idea of shutting off my work laptop and turning around to work on a corporate tie-in novel about some franchise someone noticed me talking about on social media turns my stomach with a cold lick of dread.

For me, art should be selfish. Self-obsessed. You should follow your every impulse and desire to create something that feels like sitting around inside your head when I open it up to flip between its pages. Every quirk and kink and eccentricity laid bare. It sounds so wanton to put it like that, but it's just because, in the moment, when reading something that feels so much like its maker, the experience is electric. I feel that way reading JoJo's Bizarre Adventure by Hirohiko Araki, Pink by Kyoko Okazaki, or Buffalo 5 Girls by Moyoco Anno.

I feel that way when I write.

But lately, I find myself feeling that way when I write non-fiction. Essays. Criticism. Whatever you want to call it. The things you read on your phone when they appear in your inbox every month or so.

My essay-writing is selfish. I'm talking about the art, yes, but I'm mostly talking about myself. My relationship to art. My relationship to my own history through the membrane of art.

It feels like telling the truth in a way that fiction hasn't felt for a long time.

I don't believe art is, in itself, selfish. It's the communication of stories and ideas and symbols, a direct line from the artist-speaker to the audience-receiver. The line is unraveled in a million possible directions, twine wrapped around one tongue that splits and frays forever and ever. The artists whose work I enjoy do this for the sake of art, for the sake of self-expression, and also to sell a product and pay their bills. There is no righteousness or divinity in this. I don't know what's true or real in the works of my favorite artists. It's just a feeling. I don't know them any better or worse now that I’ve read their work than before I’ve started.

Certain things feel true. They become truth to me.

Certainly, some of what I’ve said feels true to the people who have read it. So I’ve heard, anyway.

At the end of the day, only I know the truth about my writing. And the only truth I care about in the art I engage with is the one I find, or make, for myself. It is an insular experience, and the only person I care to please, entertain, and learn more about is myself.

So if that is how I feel about my truth, what does this say about my fiction?

Never to find our way back

I think a lot about zines. I don't make them, but because of my proximity to a lot of artists and illustrators from different corners of the publishing process, I think about them quite a bit. Things drawn with ink and pasted together. Printed, copied, folded, stapled, handed out. Passed around. It's here, then it's gone. Keep it while you can because another won't be printed.

I think about vaporwave in this way, and the innumerable subgenres and variations beneath its frequently mislabeled umbrella. The songs are made from samples, commercial jingles, Windows start-up tones. Chopped and screwed marketing materials and digital ephemera attempt to elevate mostly forgotten refuse to the status of art for a handful of listeners.

This is music made to be experienced in a very specific context. It's made by a small group of people for an equally small audience, and then left to the wilds of time and entropy. Maybe it will get a physical release. Maybe it won't. Once the file disappears from Bandcamp or Spotify or some other streaming platform, it's gone forever.

I feel the same way about my first book. My next book, too, if I'm being honest. I don't think of books as permanent objects, or examples of my commitment to craft. I try not to own any book I've ever released. Seeing my own work on the shelf fills me with an intense wave of panic. Or, rather, it used to.

These days, I don't know what it would inspire within me. I've gotten rid of every copy I've ever received. Some I've sold to thrift stores or secondhand book shops for a dollar or two. Others I hid away in tiny libraries all over town. Sometimes I think about giving all my work away for free. I often do. This year alone, I've given nearly 800 copies of my books and stories. It feels more natural to me. I believe every artist should be compensated for their labor, of course, but as I’ve said, my writing is selfish. It doesn't feel like it should be worth anything to anyone else. I’m never fully convinced that it is.

When I say I'm happy my first book doesn't exist anymore, people look at me strangely.

“You shouldn't be so hard on yourself,” they say.

“You should trust the person you were at the time who told the story that needed telling.”

“Art belongs to the audience. You don't get to take it back.”

But I disagree.

Because I am selfish, and because I choose entropy over the permanence of art as an object enshrined with power.

You had your chance to read the book.

It's gone now.

That's okay.

It has to be okay.

I was rain and I wanted to be the ocean

Maybe this sounds tacky as someone whose writing is generally preoccupied with trauma, but I'm kind of over trauma narratives. Not narratives about trauma, but trauma narratives as a selling point. An item on the book marketing checklist.

I see it a lot on social media. Writers lining up to talk about how the book is about this or that trauma. It's an important book, you know. Because of all the trauma. Talking about trauma is important, on account of all the trauma. You can't be funny or interesting without it, or so I’m told. It's like seasoning in food. Salt and pepper to taste.

Come to think of it, I see it most often in discourse around pop culture. How important it is for Disney or whoever to make another show or movie “about” trauma. All I ever hear about is how the Marvel Cinematic Universe is dealing with trauma, like a Very Special Episode of Blossom. It's so important that merely mentioning it, gesturing to its impact on a character, overrides any criticism of story or plot, characterization or style.

To me, trauma is like a snow globe. A moment in time suspended in water and glitter. In fiction, it can be beautiful in certain lights, but is often just kind of cheap. Simplistic. Unexamined. Mass produced for public consumption.

I just spent four months in a PTSD treatment program. Trauma is everywhere. It is the ambient temperature of any given room. It's worming around under your clothes and tickling over your scalp whenever you feel nervous or out of place. You're foolish if you think otherwise because trauma makes a fool of you. It tells you that you are alone and you are special and you are unique and no one, no one, suffers as spectacularly as you do.

I’m tired of talking about it, honestly. Everyone has it, and rarely does anyone have anything interesting to say about it. They’ll wear it like a badge or a shield, polishing and brandishing it. Hiding behind it when necessary, but offering nothing beyond just…its existence.

I'm tired of giving trauma all this credit for my personality, intelligence, or talent.

I'm tired of giving it air.

I'm tired of giving it books.

I was a star and I wanted to be the sun

The next book I’m working on is my best work yet, because it isn't about me.

It started off about me, sure. The then-protagonist assassin Lautaro was the elder child of immature, unprepared parents, the load-bearing son who propped up the family. He found himself rushing into a family of his own too young and struggled to live a normal life. His spy wife Alyena was a flight risk of a person who saw how much of their marriage was rooted in him making up for the mistakes of his own wayward father. She fled their marriage when she realized she was being strangled by his ghosts. And, yeah, it was cheeky and a bit poignant to see such dangerous people having such banal trials and tribulations as unprocessed trauma.

But that book kind of sucked, and so I started over.

Now it's about a marriage between a spy and an assassin in a world without guns, and the tensions between the different kinds of people who are allowed to enact violence. It's a globe-trotting soap opera about two killers not like in dignity; a free-wheeling thriller about a marriage of star-crossed lovers that is blown apart by the machinations of spy programs and corporate assassin guilds. They are terrible. They are funny. They are cool. Their love will burn the world and everyone in it, and we will root for them.

Alyena took over the book, because she's the coolest character I’ve ever written. She sings songs to herself and makes faces at her reflection, and she loves her husband and daughter with an all-consuming fire. Lautaro is still her co-star and the object of her obsessive affections, just as she is the object of his, but he’s the tiger at her feet, a man happy in her bondage and desperate to get her back. Their daughter Hazel is a cunning and manipulative (in her mind, anyway) four-year-old who loves frogs, is scared of sharks, lies compulsively, and is getting a crash-course in what it means to be a killer's child when her easy life is shattered.

They feel nothing like me anymore. Their stories feel nothing like mine. They don't have to honor my pain, the names and places changed to protect the innocent, because that pain isn't encoded in their DNA. Alyena is the little butcher bird who dreamed herself a life she wasn't built to keep. Lautaro is the tiger who caught her in his maw and will kill whoever he must to keep her safe. Their child was never meant to be born, but Hazel was, and now it's everyone's problem.

It makes me so happy that they live so far beyond me and what I know of pain, because now I feel like I can tell the first honest story I’ve ever told.

They want from us what they cannot touch

What I haven't told you is that I have, on no less than three occasions, planned to re-release Fleshtrap. I made new covers, started updating and reformatting the manuscript, and gave myself concrete deadlines for release dates. I even made tenuous announcements about it on social media.

Then nothing ever came of it.

Again and again, I told myself that if you have a book, just put it out.

Again and again, I failed.

Each time I sat down to work on the covers, I felt a little sicker. Reading through it again to fix minor errors and reformat the interior made my skin crawl. My stomach turn. My ribs sweat. You will tell me that it's just the embarrassment talking, a natural reaction to reading a decade-old story. You will tell me to push through it because the story should be told.

It belongs to the world now, and I need to trust myself in what I have to say. People will enjoy it for what it is. Releasing it only puts more art out into the world and into the hands of people who may need it.

Some very kind people have said as much over the years. That it was cathartic. Relatable. True to their own experiences of abuse.

I appreciate hearing that. I do. It makes me feel like I told the truth in a way that meant something to someone else.

But I can't let them have the book back.

Not this time.

Maybe never again.

The thing about my first book is…it's all a lie. I told myself that it was written to process my own experiences as a child, and touch on those of other children around me. I've described it as a primal scream from somewhere deep inside of myself. Something that needed to live on the page so I could live in my own skin.

I told myself that I wrote it about a difficult chapter of my life, and it helped me heal. It let me move on and become someone else. My tastes shifted away from writing horror to lighter fare.

But it didn't help me. Not really. Because what I wrote about was only part of the story. I buried the rest in a shallow grave with the years of my childhood that I couldn't bear to remember. The years I’ve remembered since. The years and the terror and the guilt that I continued to write about in books to come, even when I wasn't fully aware that I was still doing it.

I remember the remembering. My unbecoming. On my hands and knees on the floor at night, feeling like I was about to wretch. Feeling like I was about to scream. To cry. To vomit black bile and expel everything I was lied to about.

I've written a lot about these things in other essays you might have read. I've written even more in therapy. Shaking, sweating, panicking, writing out pages and pages about all the things I told myself didn't matter anymore. That did or did not happen. That did or did not happen the way I was told.

Even writing *this* fills me with grief and panic. Writing about the writing hurts, but it needs doing. I feel I owe it to you, my imagined reader, who has followed me through so many painful essays about art and yet I deny this one scrap of fiction.

Fleshtrap is a book I wrote about things that I forgot and came to realize that I had never truly understood. It should have never been published, but I was young and in pain. If I put the book back out today, I don't think I can live with what it represents, ten years on the other side and through months of intensive therapy.

If I revise it today, I will simply be rewriting my own story a decade later. I've already done that in therapy, and in every book I've written since I was 25. Piecing together the childhood that I made myself forget and I now must live alongside. It is a part of me now, just as this book is a part in that whole.

The truth of it is, the story *is* mine. The book *is* mine. It is my life, my heart, my fear, my guilt, my shame. As sweet as it is to know that it touched a handful of readers in the state that it first escaped my grasp, I cannot live in a world where it exists anymore.

It is a testament to my own history in ways that I no longer feel ashamed of, but simply want to grieve. If I learned nothing else in my PTSD program, it's that I have a lot to grieve for. From the child who imprinted herself across the pages of Fleshtrap to the adult who wrote it all down in fragments of time and memory.

Because Fleshtrap is mine to grieve, not yours.

You don't want to hear that. I know. Art is supposed to be yours. Once it leaves the bodies of its creators, it belongs to the world. But we cannot ask that people bare their souls on the page and then feel nothing about it once it's done. We cannot divorce ourselves from what we make and the pieces of ourselves that live on within it.

And my story, my life, is mine to take back for myself.

Nature's Corrupted is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Add a comment: