The Boy Was Never Really There

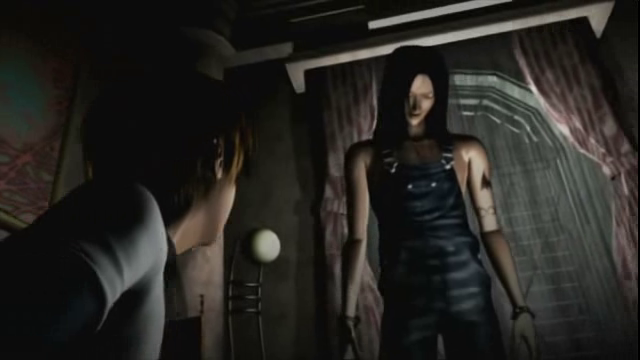

There's a scene from this movie that kind of lives rent-free in my brain. A boy, fair and slim, wanders the rainy street at night. The city breathes around him. He's mostly covered by a rain-slick jacket, with skinny legs sticking out of the bottom that end in big stompy boots. Happening upon a decrepit hotel deep in the guts of the city, the boy wanders into the room rented by a drug dealer.

It's a pretty stereotypical scene. A dark-skinned man, coded as generically “African" with a black beret, animal-tooth necklace, and animal-print vest, emerges from a door behind the boy. His shelves are full of canisters of herbs and powders, the tops lined with small boxes. The boy barely has time to remark upon any of this before the man regards him knowingly.

“You’re a new face. You're just a kid.”

The boy asks about his friend, a lost girl named Lilia. He isn't here for drugs but information. The man circles him to take a seat on the nearby sofa, cigarette hanging limply from his mouth.

Chuckling, the man draws on his cigarette and says, “You're just a kid, but you're already addicted to drugs. You're a wild kid.”

The boy looks taken aback by that.

“How did you know?”

He doesn't deny it. He doesn't think to deny it.

Leaning forward, the man appraises him. The drug dealer's keen eye identifies the boy’s rough skin and sickly appearance. That makes boys like him a good customer. The man laughs at his own joke, and the way the boy leaps at the offer of hard drugs.

I think about that scene a lot. Weekly, at least. Maybe every day, somewhere in the back of my mind. A boy with skin like a brittle leaf, a hollowed out look in his eye. A dealer who smiles and hands him vials of candy-colored chemicals.

This scene is never remarked upon again.

2025 feels a lot like an apocalypse. My only framework for the end of the world, however flimsy and fleeting and made of tissue paper it feels in comparison, is 1999. The 21st Century sold on television used to be clean and new then. It felt like holding a light in my hand whenever I thought about what it could be like to see the future, a flash of something, dizzying, dazzling, and bright.

I was the kind of child who watched too much History Channel and read too many books on Nostradamus. I was just as convinced, deep down inside my bones, that the world would end in a flash. Not quite a mushroom cloud but a swell of bright, hot light. Like in Akira. Like the kind that poured from cathode ray tube TVs and screens and puddled on darkened floors when I was up alone at night.

But I wanted to believe that I wasn't living, to borrow a phrase from Francis Fukayama, at the end of history. I wanted to be wrong about apocalyptic prophecies. Y2K missed me by a mile. All I had left to worry about was global warming and great famines and floods and bright, beautiful balls of light. In the years since 1999, I can't say my fear of the 21st Century has really left me. It did manage to change its shape, I think.

I've lurched forward and backward through the stages of grief. Denial, anger, bargaining, depression. I let apathetic optimism consume me by placing my trust in systems on the promise of comfort. Constant outrage simmered down into a performative anger and eventually a kind of intellectualized detachment. Deeply inane sentiments like “How can you be happy when you know things are bad?” crossed my lips on more than one occasion.

Then I reached past reflexive anger and grasped for the familiar contours of despair. It was the kind that had me bursting into tears on the drive home from work, thinking of koalas burning to death in bushfires or polar bears starving in the arctic.

This was all before 2020, in what people might one day be nostalgic enough to call “the better days.” I don't want to get too far ahead of myself with such lines of thinking. My grief had already metastasized into something that I no longer recognize when looking behind me. It was a burden grown heavy upon my back, something that left me bowed and bent beneath its expanding mass.

Now, it's 2025. Next year, I turn 40. Ain't that a bitch? I've cut away at the mass of fear and grief and rage that clawed its way out of my spine to sit at the base of my neck. It's still there, of course, but I've shed what I could and sutured the wound. The 21st Century is no more my enemy than I am its victim. I live alongside grief like a companion. It's a presence at the dinner table, a familiar shape in the passenger seat when I'm alone for a drive.

Why, then, do I want to talk about apocalypses today?

Why, then, do I find myself reaching for things from those fretful years at the beginning of the 21st Century?

Why, then, do I keep returning to the boy in the hospital, the girl in the hotel, and the goddess in the tower?

Galerians: Rion is a 2002 computer animated OVA (or original video animation, for those of us who didn't grow up on anime VHS tapes and torrent sites). It was released by Enterbrain in Japan as three episodes/volumes, each released on DVD in April of that year, with a North American release in April 2004. Later combined into a 73-minute feature film, it was licensed by Image Entertainment and first broadcast in English for American audiences on MTV2 in July of 2004.

If you were an American kid or teen with cable access in the mid-2000s, this was probably how you encountered Galerians. Not as a game series, but as an animated oddity. A kind of chunky, kind of clunky Japanese cartoon movie with a soundtrack full of Skinny Puppy, Fear Factory, and Adema. It appeared randomly, from what I remembered, on weekends or late at night to fill up dead air. Cable network syndication could offer little surprises like that sometimes.

But that's just the basic trivia. I meant what I said before, about the oddity of Galerians: Rion. The OVA was developed by Polygon Magic, the same studio that developed Galerians and Galerian: Ash. It was directed by monster designer and cut-scene director Masahiko Maesawa, with writing credits for series writer Chinfa Kan, character designs for series designer Shou Tajima, and score for series composer Masahiko Hagio.

From what I understand of scant articles on the English-speaking internet, the OVA was developed in-house by much of the same team, using the same engine as Galerians: Ash. One may expect a third-party adaptation for a project like this, like the light novels penned by Maki Takiguchi, but it was a product of the same team.

Galerians: Rion created a visual bridge between the original PlayStation game and its PlayStation 2 sequel. In using clipped sequences of the late 90s cutscene animation for flashbacks and flavor, it honors its lower fidelity roots while still updating the characters and their designs for a more sophisticated engine. The animation from the OVA was then chopped up and repurposed for the prologue sequence in Galerians: Ash. It becomes difficult to fully separate these three works from one another in this way as they blend and melt together across platforms and mediums.

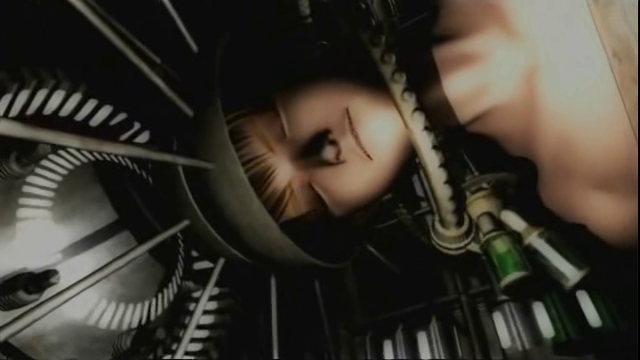

Serving as this middle point between late 90s mid-budget PS1 game development and the impressive hardware of the PS2 in the early 2000s, Galerians: Rion is a fascinating thing. It retells the first game's story beat for beat. The frenetic opening song recreates the game's credit roll, replacing the groovy drum and bass of Release Me with a driving, thumping beat intermittently pierced by Rion's grunts and cries of pain.

Sequences of the OVA are stitched together in a dizzying montage with words like pain, despair, hate, death, and anguish flashing starkly across the screen. It's the same characters you love displayed as harshly as possible, laying off the very 90s green distortion of code and computer hardware for the sterility of polished chrome.

It's not bad, it's just different.

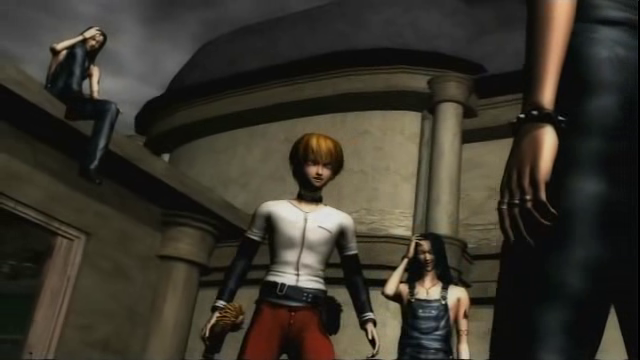

Rion Steiner awakens in a hospital with no memory and a girl's voice in his head. He is older here, sharper, the youthful roundness of his PS1 face given an angular redesign. In Japanese, he's played by Akira Ishida, and by David Wittenberg in English. Ishida gives my favorite performance of the character, lending a breathy, dreamy quality to Rion whenever he isn't screaming in agony. Wittenberg turns in a good performance, though the fact that he also plays the antagonist Ash in the sequel game kind of trips me up.

Escaping his nightmarish confines in the bowels of Michelangelo Memorial Hospital, Rion finds he has been cursed with devastating psychic powers. The voice in his head leads him to make his escape as he blasts and burns his way past scared scientists, nervous shock troops, and battle droids. Rion is more outwardly violent in the OVA, in a way that I don't know if I love for the character but makes sense enough from an adaptation perspective.

The psychic power enhancing chemicals (PPECs) that were so heavily emphasized in the game play a smaller role here. Rion is no longer a confused child but a more mature-looking teenager or young adult. It makes the ensuing violence (and drug usage) go down easier than in the original game.

The dramatic whiplash and frequently rotating camera portrays Rion and his world in constant movement. Rion dashes briskly from conflict to conflict as the script condenses his gradual acclimation to psychic powers into sequences of raw, explosive force. Violence comes easily to him, an instinctive act. Instead of his adversaries feeling like threats, they cower before him, expressing fear at the sight of this monstrosity before having their heads exploded or bodies destroyed by explosions of white light. Here, Rion is someone to fear.

It's not bad, but it is different.

I'm going to be saying that a lot, aren't I?

He's also held at greater distance from the viewer than he was the player. Without gameplay to explore Rion's powers alongside him, interspersed with slow, fairly static cut scenes of his quiet contemplation, we are speeding through the events more violently. Rion doesn't get a moment to reflect on his circumstances and collapse into exhausted resignation until after his fight with Clinic Chief Lem.

Instead of fighting the imposing adult (who turns out to be an android for loose thematic and vibes reasons) through combat, he defeats the evil hospital administrator by short circuiting in a blinding, screaming fury. It's only after a series of violent encounters that threaten to rip the hospital apart that he's allowed to be vulnerable, at least emotionally. Allowed to be a tired teenage boy rather than a demigod.

Once Rion flees the hospital to return to his home in the country outside Michaelangelo City, I think the OVA hits its stride. Things slow down as Rion explores Steiner Manor. He uncovers his identity and memories through visions, absorbing the psychic residue of his family's once idyllic life. The Steiners were a happy family with father Dr. Albert Steiner, mother Elsa Steiner, and son Rion. He had a lifelong friend, a little girl named Lilia Pascalle (voiced by Shiho Kikuchi), the daughter of his father's colleague.

His parents’ memories unfold in black and white snapshots, his own life told to him through their eyes. Moving through these scenes, he watches their murders at the hands of the psychic child Rainheart.

What felt tense and eerie in the game feels like a genuine gesture toward horror here. Rion is being trailed by featureless, trench coat- and hat-wearing henchmen called Rabbits. Birdman has been following him, too, a slim older boy with a cackling laugh played by Takehito Koyasu (the illustrious Dio Brando of JoJo's Bizarre Adventure). This boy has the power to teleport and duplicate himself.

He and his little brother Rainheart are in the house with Rion, turning this leg of the story into a hunt rather than a plodding exploration. Seeing the brothers together interacting, however briefly, is a welcome change of pace from the game. Theirs is a strained sort of sibling love, perhaps more tolerance than love, but it's nice nonetheless.

The Steiner Manor section juggles a lot of revelations. Rion discovers his past, his parents’ murders, and the secret inside his brain. He was a normal boy once, who spent time playing in the yard with Lilia. Then their fathers, scientists both, created the artificial intelligence Dorothy to help run the city. Dorothy was just one of the computers who maintained Michaelangelo City, but soon she outgrew her programming. She became fully sentient, and with that sentience, came the desire for power.

Dorothy imagined herself as god to usurp man on the throne, ruling over a dominion of her own making with creatures born in her image. She called these creatures Galerians, psychic children fed drugs and forced to do her violent bidding.

As the super computer took over the city, Dr. Steiner and Dr. Pascalle plotted to destroy Dorothy. They created a virus program and split it in two: the virus implanted in Lilia's brain and the activation program implanted in Rion's. The good doctors weaponized their children against their creation. Dorothy discovered the plan and sent her creations, her army of Rabbits and Galerians, to kill her creators.

Lilia was sent into hiding. Rion was captured and sent off for brutal, dehumanizing experimentation by Lem. Lilia is alive somewhere in the city and calling out to Rion for help, waiting for her friend to come save her. Before the end, Rion has an explosive encounter with Birdman, who laughs softly and wishes him well before bleeding to death.

The following Babylon Hotel sequence sees Rion wandering back into the cold and unfeeling city, following Lilia's voice. He has direction now: his memories were stolen when he was given powers, punished by Dorothy's loyalists for his father's sins.

On the train, he laments being forced to kill Birdman, the horror of his own actions weighing on him in quiet moments. Grief, rage, or the desire for comfort don't drive him as he arrives at the hotel, focused instead on reuniting with Lilia and stopping Dorothy.

Here, he meets the aforementioned drug dealer Joule from the beginning of the essay, the murderer Rainheart (voiced by Kenichi Suzumura), and the third Galerian Rita (voiced by Yuka Imai). This section of the story is considerably slimmed down without the gameplay loop to pad out Rion's time at the hotel.

In the game, Rainheart continues his murder spree to find Lilia, killing the hotel staff and its troubled guests. Rion's encounters with the humans of Michaelangelo City showed the ugliness of its population, zealots and terrorists and miserable dregs all.

The lack of this storyline in the OVA dramatically truncates the section and diminishes a lot of the oppressive mood. I understand not wanting to dedicate time to walking around meeting strange hotel guests without a mechanical impetus, but what remains of it does feel lopsided. The scene with Joule plays out as it does in the game, but without that rotting sense of humanity surrounding it, the whole thing kind of loses its impact.

To say Rion is a drug addicted child is shocking, but Joule feels like a one-off. The presence of other menacing or pathetic humans makes Rion clinging to the idea of Lilia all the more poignant. Even the doctors and shock troops of the hospital segment have been defanged, left terrified of the all-powerful child they strive to contain. That sense of doom and tragedy does leave the OVA a bit lacking in many ways.

Rion encounters Rainheart rather abruptly and at the other boy's death, we see that he was tormented and drugged. He was forced into medicated compliance and engaged with his sadistic impulses only when in this state. The added touch of Rainheart setting all clocks back to avoid the stroke of 3PM, and with it his daily injections, does give him some brief but needed pathos.

Rion enters the white void of Rainheart’s memory to see Clinic Chief Lem terrorize the frightened boy before Rainheart dies. Giving Rion that moment to empathize with, and potentially forgive, Rainheart provides some of that emotional texture that's been missing in this leg of the story.

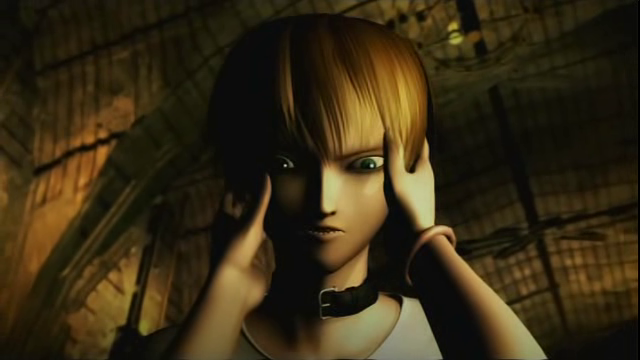

When Rion finally reunites with Lilia in the restaurant secreted away in the hotel's basement, their moment together is a momentary respite. Lilia is weakened by her telepathic communication with Rion throughout the story, a strange idea from the game that's never been remarked upon. Though she isn't a Galerian, she is telepathic through unclear means, and through her connection with Rion, she feels all of his suffering. The pain that Rion puts himself through to save Lilia hurts her, too. She manages to hold his face in her hands for a moment before collapsing weakly.

Rion is…cold here, I think? Maybe numb. It's a bit sad how little he expresses compared to the original game, his older, more angular character design less prone to open emotion.

Before they can leave, the pair is ambushed by Rita, the third Galerian and Rainheart’s fiercely loyal older sister. The fight here is short but memorable as Rita's rage channels into controlled chaos, taking up tables and chairs and silverware to hurl at Rion like bullets. Rion overpowers her and Rita, at the end of her rope, injects herself to initiate a short circuit.

Like in the game, Rion can't hate Rita, trying to help her even though she's hurting him and Lilia. Rita embraces Rion as her brain is engulfed in electricity, and he follows her into that white void to see Rita's self-loathing and pain.

Her wish for non-existence is expressed somewhat simplistically as Rita lying in a puddle of blood flowing from an opened vein. As Rita confesses these feelings to Rion, seeing him as a fellow traveler of sorts, the image of deep red, almost black, blood splashed starkly against the white space is striking.

Rion honors Rita's wish to die and kills her, even as Lilia begs him not to. He can't hate any of his pursuers, after all. They were tortured by Dorothy, forced into this life. Killing them is differentiated as an act of mercy rather than mere violence.

To its credit, where it sacrifices the creep factor of the hotel, the OVA gives us more time with Rita, like it did with Birdman and Rainheart at the manor. I only wish it had the same considerations for Lilia. I understand the idea behind keeping Lilia at arm's length from Rion as the story moves to its closing section. The games have always treated Lilia as a character with her own, much bigger story that the player is merely passing through as Rion. I just think they could have spared a few minutes, maybe a few more lines, for Lilia but chose not to. That's disappointing, ultimately.

With all the Galerians defeated, Rion and Lilia go to the Mushroom Tower where Dorothy rules over the city. We are immediately confronted by the body horror science fiction hidden at the heart of the story. Dorothy's tower is a cathedral of flesh and sinew, tendons and umbilical cords stretching across the metal walls. Everything is fleshy, pulsating, and wet.

Without enemies or puzzles to extend the time spent here, Rion and Lilia quickly meet with Cain, the smirking, leather-clad boy with Rion's face. Cain explains the big twist: he and Rion are clones, the original Rion Steiner is dead, and Dorothy implanted Rion's memories in the body of a lookalike to lure Lilia out of hiding.

All of this was part of Dorothy's plan to kill Lilia, the only true threat to her power.

So, as with the game, we are left with many questions.

Why did Dorothy put the activation program in the clone's brain? Why are there two clones? Why is one clone named Cain and the other Rion? Shouldn't his name be Abel? Why does the clone have amnesia? How can Lilia be telepathically linked to the clone? Why did Dorothy put the clone in Clinic Chief Lem's possession? Why didn't the other Galerians seem to recognize the clone they theoretically grew up with?

The answer here just as in the game is it doesn't matter. Galerians exists in a rather vague, impressionistic reality. The only question that matters is what Rion will do with the truth. If he believes he's Rion, he will follow his instinctive love for Lilia and destroy Dorothy to protect humanity. If he believes he's a clone, he will follow his instinctive loyalty to his mother-god and kill Lilia.

But Rion chooses humanity over the Galerians and kills his brother Cain. He defies his programming and confronts Dorothy with his choice. Even if he is nothing more than a clone, he is not her puppet or doll. Taking Lilia by the hand, Rion activates the program in his brain and uploads the virus in Lilia's into Dorothy's system.

The final confrontation is brief but beautifully telegraphed, with two small figures dwarfed by Dorothy's feminine monstrosity. Her great red face is crowned by a head of hair-like cords, the placid closed-eyed expression a strange contradiction to her vivisected torso with its exposed flesh and tubing.

Uploading the virus is a euphoric, otherworldly sort of victory, and is punctuated by the violence that solely defines Rion's existence. Dorothy dies screaming and so does Rion, his brain overloaded and short circuiting. Lilia holds him as he breaks down under the strain.

In the white void where his siblings died, he finds peace. He wants to rest here in Lilia's arms. He's finished his mission and lived up to his purpose. As Lilia looks out over the city below, it's up to humanity to decide how to live in a world without Dorothy.

For all of my nitpicks and complaints, Galerians: Rion is an impressive little creative feat. It's a visually exciting and well-executed retelling with its share of striking images. The voice cast turns in some great performances, and the score is pretty great, too, I have to say. In reusing cut-scene animation and music from the game, the OVA is making use of those strengths, keeping that mood and tone present despite the upgraded visuals.

That this was largely the same creative team, working in-house to create Galerians: Rion rather than an outside team taking on the project, makes its existence as an adaptation a little fraught. I wouldn't treat this the same way that I would a live-action movie or a light novel. The translation between the different languages of mode and medium preclude direct comparison in those cases.

Here, it's more of the story told by its tellers. Galerians: Rion is kind of like a victory lap in some respects. The team made the game, and now they get to reimagine it in a different form using different technology. Taken from that technical perspective, the OVA is a leap forward, and I would wager a very successful one at that. But the devil is in the details.

Because it's mostly the same team, with the same core people involved, we can clearly see what mattered to them. What felt quintessentially Galerians. We get to see Rion embrace the full destructive force of his psychic powers. We get to see the Galerians themselves realized with more pathos and interiority. The world is polished, slick, and yet nightmarish. It blends elements of mid-century urban rot with Y2K futurism throughout its runtime, before melting into Dorothy's bloody biological corruption.

In seeing what was retained or added in the process of adaptation, we can also see what mattered less.

The lack of gameplay to account for lets Kan smooth out some narrative events to focus more on mood and story. On the other hand, that lack of gameplay takes away from the slow, plodding, lonely exploration that I feel helps define Rion as a character. He is a sad, isolated boy, now made a more hardened and powerful young man.

Without that time spent with him, he's just running from battle to battle. Moments of quiet and solitude are sprinkled effectively throughout the OVA, but that tight runtime doesn't give him much room to breathe. His relative quiet as a game protagonist felt like reflection; here, that silence gives his character an aloof disposition that makes Rion difficult to connect with here.

Joule the drug dealer reads a lot into Rion, but it doesn't feel like any of it's even really there. We have a boy who's addicted to drugs, but those drugs are presented as less important and impact him less, are less thematically loaded, than in the game that scene comes from. It just feels a bit empty, you know?

This is all the more true of Lilia, who fades into the background despite being the core of the story. Without Lilia, there's no Rion, no mystery, and no conflict. I find it disappointing that the team thought to include more moments, however brief, for the Galerians, but Lilia feels even less of a character than she did in the game. While I can get behind the sparseness of characterization, especially when certain nuances can be communicated through imagery or animation, I just don't get how little Lilia seems to matter when she's Rion's only connection to humanity. It doesn't feel intentional, it just feels like a blindspot.

I don't think it would take much to flesh her out, either. When all she has is some breathy voice overs and a glimpse of her in hiding before she faints in front of Rion, the story loses the opportunity for much needed texture. Just give her some moments, not even full scenes necessarily, of her life on the run. Impressions sent to Rion in flashes: running down rain-slick streets in loosely-tied boots, scavenging for food from dumpsters, piecing her clothes together.

We don't have to see precisely how Lilia survived on her own evading Galerians because we know that she did, but give weight to that desperation. Light a fire under Rion's ass. If nothing else, let her experience relief at seeing her friend. Allow her that moment to feel. To grieve. To stand silently in the rain with Rion.

Even for my gripes, I can't be mad at Galerians: Rion. It's a fascinating little oddity that in some ways improves upon its original form and in others is less successful. If you want a brisk little sci-fi joint that's confident in everything it sets out to do (sometimes to a fault), this OVA is fun. I like it. But I don't love it the way I love the games, and I think that's because Galerians should be a game.

Coming back to Galerians: Rion, I wanted to answer a question that's been bothering me for two decades now. Does Galerians have to be a video game to be successful? Taking it as a whole, is it more compelling as a game or a film? It's not a question I ever ask of other works, but the discourse that's surrounded this series for these last two decades all but demands an answer.

For years, my understanding of Galerians’ place in the Western, English-speaking imagination is that of an interesting story with compelling visuals hindered by shallow, clunky gameplay. It's slow, it's often frustrating, and the combat mostly sucks. If you forgive its blemishes, there's a story and world worth experiencing.

If you remove the minute-to-minute experience of playing Rion, an amnesiac child surrounded by adults who want to hurt him in a world he doesn't belong to, you don't get that. You get a sense of it, sure, but it just doesn't hit the same.

Playing Rion makes you feel as small and lonely as he does, a crunchy little figure in an overtly hostile world. Watching Rion doesn't impart the same sadness, especially when he's built to better withstand that world. Michaelangelo City doesn't feel as strange, the enemies as menacing, the mood as oppressive.

It isn't bad, but it is different, and I think I would rather play the game.

But I understand why some people wouldn't, or can't. That's why I think you should watch Galerians: Rion. It's the easiest, most accessible way to experience the story. It's free to watch on the Internet Archive or YouTube. Most of all, it's a sad, weird, deeply empathetic little series made by people who cared about this story enough to tell it twice.

Rion is a pretender who wears a dead boy's face and chooses to kill a god rather than betray the love he feels for a stranger. He chooses to forgive his enemies when he sees their pain, and watches over them as they die because these are his feelings. Those are his instincts. Not to destroy but to bear witness.

That's still beautiful to me.

If this is the only way I can convince someone to sit with Galerians, after three essays and many hours of work, then I'm glad for it. I can think of few stories that feel as relevant to me in 2025 as Galerians.

You may feel the same if you give it a chance.

All images courtesy of the Galerians Wiki and IMDB.

Add a comment: