Stories, Like Houses, Grow

There's an excellent chance that if you ever asked me what the most important story in the world is--

The most important story to me is, the most relevant, the most impactful, the source of everything that has made me the human being I am today--

I would tell you it's Neon Genesis Evangelion.

But that might not be true.

The thing about Neon Genesis Evangelion is that...I can't talk about it. Or I couldn't, anyway. For twenty years, talking about Evangelion put a gnawing, aching fear in me that I couldn't express. The kind of fear reserved for nights alone in the dark, thinking about God. It sutured my mouth shut with wire in polite conversation. It burned my fingertips when I touched a keyboard or phone. As if struggling to speak the name of one's maker, the architect of you, in all the ways you are complete and whole and yet simultaneously unmade.

Made and unmade. Cells interlinking cells. Bonds severed. Transmissions lost in the void.

So I just...didn't talk about Neon Genesis Evangelion. And I kept not talking about it for two decades of my life.

I lied about it.

I forgot about it.

I rewrote what memories I did have of it until I wasn't present in them anymore.

Until I couldn't anymore.

So, with a fear reserved for thinking about God, allow me this chance to tell you why Neon Genesis Evangelion is the most important story in the world.

A childhood spent in a hotbed of maladaptive coping mechanisms and other people's unchecked mental illness did not make me into an ambitious person. There was really no point in trying to do anything in a house like that. Trying took effort and could result in failure. If you didn't achieve complete and immediate mastery of something, you should give up. Giving up was better than failure because you could at least spare yourself the indignity of disappointment or inconvenience.

Everything was stacked against you, after all. Everyone was out to get you. Other people were just obstacles to your happiness. But your happiness was found in serving the whole. The family unit. So you should not only refrain from wanting things because the effort it took would have been a waste, but because they were out of your reach. You didn't deserve them because your desires didn't serve those of the family.

Growing up this way didn't teach me to want things. However, it did make me into a determined person. You have to be determined when you're raised like that. No one else will be determined for you.

I have been a writer for as far back as I can remember. When I was six, perhaps seven, I started hand-writing stories in cheap spiral-bound notebooks and on pieces of scrap paper. By the age of ten, I drew comic books on printer paper, figuring out ways to staple them together so that they could be read properly. I wrote what I thought counted as novels on the family computer with a primitive children's storybook-making program. My eleven- and twelve-year-old self wrote longhand X-Men fanfiction before I knew what fanfiction was. Later, when I had access to a secondhand word processor rescued from the Lost and Found at my father's job, I wrote stories about spies and assassins.

At thirteen, I strolled into the kitchen and told my parents that I wanted to be a comic book writer and work for Marvel Comics. I would move to New York City and write about superheroes. My father sneered at me. Writers didn't make any money, he said, and New York was too expensive. I said that I would just work a day job and find a way to pursue my goals.

I never made it to New York, except for a 2012 trip with my girlfriend, Melissa. Without ambition, I never made my bid for a comics career. Eventually, I wrote a few horror comic scripts but the projects never went anywhere. There's one comic with my name on it out in the world, an adaptation of a short story I wrote called Ain't No Grave. It ended up on consignment at a comics shop in California. Last I heard, it never sold any copies. I went on to write novels and short stories instead. I even wrote a book about superheroes, but not the Marvel kind.

Once more, a lack of ambition put a cap on my desire for a writing career. That was for other people who were built for the labyrinthian world of publishing. People who wanted to make money and be famous on the internet could have it. I would consider myself a pulp writer, a craftsperson who strives to make art and tell meaningful stories. I write out of my own curiosity and to satisfy my own creative desire.

I just want to be good at what I do, and respected for the care that I put into it.

I say all of this because I want you to understand one thing about me before we begin this essay.

My primary fascination has always been with the topics of death, trauma, romantic and erotic love, and the endless, often uncomfortable complexities of familial relationships. All my stories are basically the same, if you ask me, whether they're about superheroes or vampires, assassins or spies. They tell the same kinds of stories about the same kinds of things. Abusive, neglectful, or absent parents. Traumatized children. Traumatized adults clinging to one another. Cycles of death and rebirth. Trauma and healing.

But every book is, at its heart, a love story. It is a love story about one person who believes they are unworthy of grace, and another who bestows grace upon them.

Over and over, I will tell this story.

Over and over, because it is the story that I think that I was built to tell.

That's why I have to talk about Neon Genesis Evangelion.

You don't know how you're going to be unmade until it happens.

Welcome to March of 2021. It's the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. I've been dealing with survivor's guilt, relatively safe in my five hundred square-foot unit on the top of my apartment while I watch the news of the world below drip down my screen. Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon a Time has just been released in Japan. I'm sitting in my apartment in Florida, and I'm cycling through the stages of grief. I don't even entirely know what I'm grieving until I see the news on social media.

The final film in the Rebuild of Evangelion series is out. I'm working from home in a tower while my girlfriend works a public-facing job as a school teacher. My hands are useless at my keyboard. Everything beneath me is pale and faraway.

Evangelion is over.

After the delays and the set-backs and the almost universally hated third film in the series which seemed to grind the franchise to a halt, Evangelion is over. This is the final ending, the third we've been given, counting the original broadcast ending of the Neon Genesis Evangelion television series in March 1996 and the End of Evangelion film release in January 1997. If you don't count the manga. The PlayStation 2 game. The hazy nature of the licensed tie-ins and spin-offs. Evangelion has ended many times, and yet it somehow kept coming back.

Now Evangelion is over, and I feel like I'm inside a broken cockpit, a million miles in the sky.

Everyone on the English-speaking internet is mad. That's what I quickly learn as I begin scraping the internet for responses to Thrice Upon a Time. Twitter, Tumblr, forum threads. Hastily translated reviews and posts. Users arguing over lore. Users arguing over best girls. Users arguing over which pairing got shafted.

I scroll and scroll and scroll until I see what I'm looking for.

Kaworu Nagisa.

I close the window, because I feel like I'm going to be physically ill.

Back then, I told myself this is because Kaworu is my favorite character in my favorite anime, in my favorite story that I can't talk about. If I do talk about it, it feels like swallowing nails. I tell myself that this is because I'm going through a lot, and Kaworu is my favorite character. Of course, I'm irrationally, unhealthily concerned that he's going to meet the worst fate yet.

Some people back home in Texas where I grew up died of Covid or related complications. A professor, an old boss at my last restaurant job, a guy I used to know with two kids. Most people I used to know, friends and friends of friends, all got sick. It's been one month since the blizzard brought Texas to its knees. People froze to death in their beds. Others died from carbon monoxide poisoning trying to keep warm in their cars. Everyone I knew was spared, but they had no power for days.

Real people were dead. Kaworu died over and over. I didn't think I could handle seeing it again, as childish as the reasoning sounded when I thought it through. Each death was more brutal than the last. Each death sent Shinji Ikari into a near catatonic state, unmade every time Kaworu placidly died, smiling. Because Shinji was worth dying for.

We don't talk about Shinji Ikari, though.

I scroll past his name in every tweet, Tumblr post, and forum conversation. The memes, the jokes. The things I understand and the things I don't yet know the context of. That's a name we don't think about.

But I close the window without getting any answers, because I feel sick.

The movie isn't out yet in America.

Evangelion isn't over yet.

And so I make myself forget. It's easy to do when the world beneath me feels like it's screaming and burning.

Stories are fickle membranes. Cells interlinking cells. Animation cells, words on a page, images flickering on a screen, lights flickering in the dark of a crowded theater. We can't ever know each other, no matter how intimate the exchange feels, because that membrane of time and space and fiction exists between us.

I've been doing a lot of reading lately about the life and career of Hideaki Anno, the architect of all things Evangelion. It's become a hobby of mine, if I'm being honest. Honesty is hard for me. Whenever I have spare time, I find myself reading interviews, watching documentaries, and listening to Anno talk about himself. Listening to others talk about him. As an animator, a director, a producer, a mecha designer, a school boy, a perfectionist, a son, a husband, a friend.

Watching and reading and listening, in as many languages and across as many platforms as I can manage. English, Japanese, Spanish, sometimes Russian. Weird subtitles, broken translations. Nuance lost in the static of VHS rips, Japanese TV spots from 1997. Many hours long YouTube video essays and career retrospectives. Discussions with Hikaru Utada, with Hayao Miyazaki. Things pieced together through layers of abstraction and language. The artifacts left behind from analog to digital conversion.

I've watched what I believe to be a very early, if not his first, broadcast television interview. I've seen paintings he made as a child. I've seen him lecture in classrooms and talk to students. I've seen him talk about his father and the complexities of their relationship. I've fallen down rabbit holes about the notoriously troubled production history of Evangelion. I've read his creative manifestos and dug up articles on his influences. I've watched his early fan films and the Daicon III and Daicon IV Opening Animations by Daicon Film, before Gainax was Gainax. I've seen him joyfully explain Kamen Rider and Ultraman storylines.

I've read translations of his official biography on the Studio Khara website a few times by now. Taking notes and chuckling to myself, because I find the fond descriptions of his academic laziness and early lack of career ambition incredibly relatable.

There's also an August 1996 interview in the yaoi/BL magazine June that I've had open in a tab on my phone for a year at time of writing. But I'll get to that later.

Reading about a man I don't know whose work I can't talk about just…makes me feel better. What do you think that says about me?

I haven't been totally honest until this point. That happens a lot. The truth is, I've been writing this essay for a year. The essay it turned into in that time is called Made with Human Hands. I put it out in May of 2022. You may have read it already.

It had a nice ending, tied up neatly with a bow.

The essay you're reading now, scrolling through on your phone in bed or in another tab while you work, is the truth of how I got there. The manufactured peace of a completed critique. A story well wrestled with.

I have a habit of that; writing essays about essays about essays.

The truth is that some stories never end.

August 2021 arrives. I open my phone and see the news dripping down Twitter. Evangelion 3.0+1.0 is premiering on Amazon Prime. I forgot about Evangelion for five months, and now it's here.

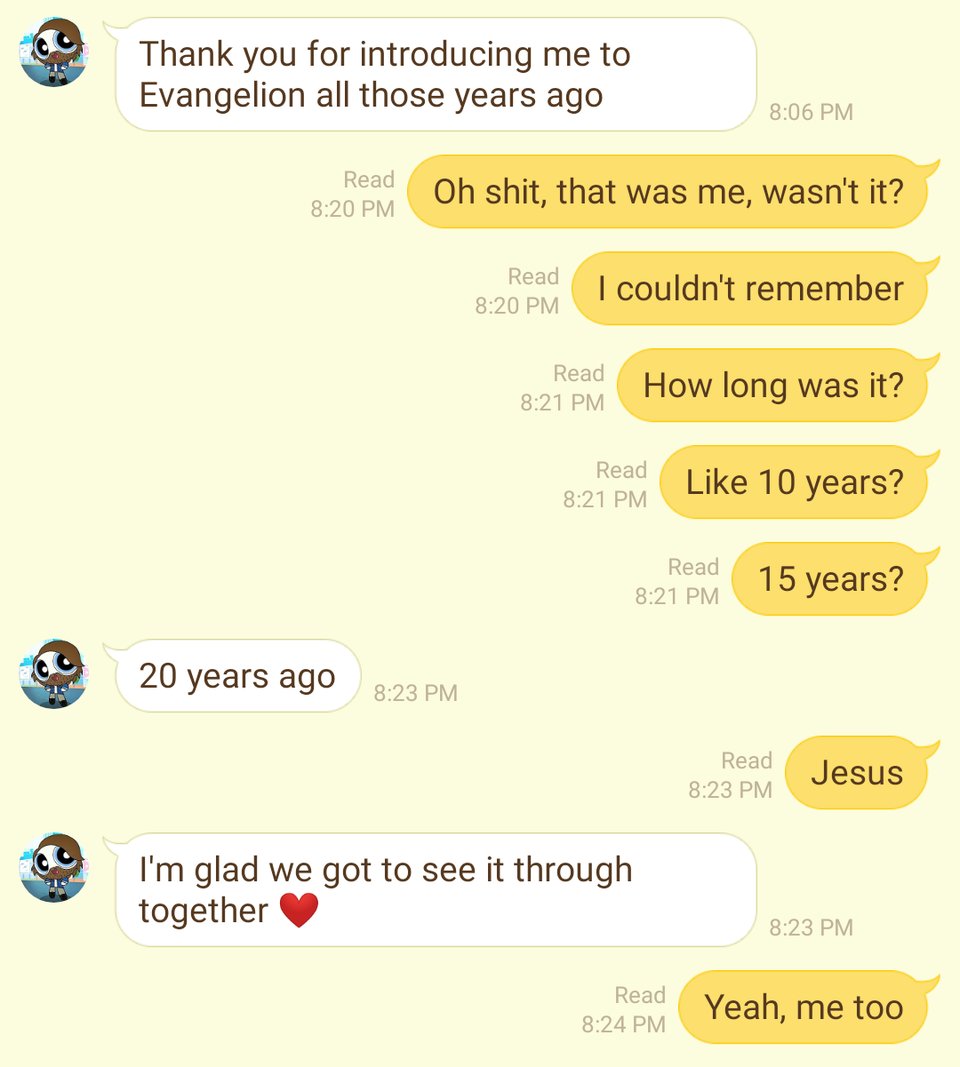

My brother, Ian, texts me the same day.

I feel sick in a way I can't describe, because when I open my mouth to try to speak of it, I feel afraid. Stupid, embarrassed, but afraid. It's that primal fear again, something that only rears its head when I'm staring at the shadows cast across my ceiling at night. As if God and all His angels are in the room,

Watching me.

I send a tweet, a joke.

My girlfriend Melissa has never seen Neon Genesis Evangelion in its entirety. I say I'll watch it with her to prepare for 3.0+1.0 coming out.

I send another joke tweet.

I'm nothing if not a performer, after all.

Privately, I message my brother. Ian, who first showed me Neon Genesis Evangelion, a decade or so ago. Who scavenged and salvaged the entire series on VHS from shelves at Goodwill Thrift Stores and the clearance section at Suncoast Motion Picture Company. Who collects Evangelion figures and statues, many of which I've had to help hunt down during the years that all things Evangelion were still hard to come by in the United States. Ian, whose whole thing in life has always been Evangelion, while I shared it with him.

If he hadn't shown me this series, this quiet show about existential despair and mechas fighting aliens in the dispassionate post-apocalypse of 2015, none of this would have happened.

I wouldn't be afraid of Evangelion's third and final conclusion.

Ian tells me he's nervous and doesn't want to watch it on Friday, when it goes live online. That means it's over again. The finality is haunting. He lives in Texas. I live in Florida. I say I'm nervous, too.

When I say we should have a video call to watch it together, he settles on Monday night after work. 5PM. He'll watch it in English, I'll watch it in Japanese with English subtitles. My brother is dyslexic and can't follow subtitles, so we would always wait to watch movies and shows together when the dub was out. It feels fitting to wait to watch it together.

All weekend long, I feel like I'm preparing for a funeral.

Me and Melissa continue watching Neon Genesis Evangelion over the course of two weekends.

That Monday, Ian and I watch 3.0+1.0 together. I clock out of my work from home job, start a video call, and turn on Amazon Prime. I am terrified.

I cry for the entire last hour of the movie.

I sit on the phone while the sun sets outside and fills the room in orange light. I weep openly as Shinji says all of his goodbyes. First to Misato, then Gendo, Kaworu, Asuka, and Rei. When he takes Mari's hand and runs up the stairs of the train station and out into the streets of Ube, I'm inconsolable.

It feels... special to have waited. To watch it together, like honoring this tiny perfect thing we've shared for the last few years.

I tell my brother that I'm grateful that we got to share this. He says he can't believe it's finally over, and Anno did what he had to do, and they all got the ending they deserved. I tell my brother I love him and hang up the phone.

I stop crying long enough to fire off a few tweets and then have dinner with my girlfriend. Everything feels like light and electricity and the reverberation of Hikaru Utada's voice singing One Last Kiss over a panning aerial shot of smokestacks and city streets.

Before bed, while my phone is on the charger, I send my brother another text. He sends this back.

The floor drops out from underneath me.

Then I remember that I forgot.

Then I remember everything.

Evangelion belonged to me first.

Everyone wants a neat story, a tidy and uplifting narrative to spend their time with. They want their fictional membranes to be clean and free of emotional complexity. You want me, on the other side of this screen, to make you feel comfortable about your choice to engage in this account of my life.

You want to see me as you see yourself, and you need me not to unnecessarily complicate these matters.

We want to see ourselves in stories. We need to see ourselves on screens. Like mirrors, they tell us that we are real and of the world, made of flesh and bone and breath. These stories remind us that we are alive, and we deserve to be alive.

I don't always feel that I deserve to be alive.

I don't always feel that I'm a person deserving of love.

I don't always feel that I should exist.

I don't always feel that I exist at all in the minds of others. I am an afterthought. A shadow. A dim light that thought itself into the shape of a person.

But you need me to tell you that you deserve this, because this is your hour, your time, your story, not mine.

And I can't tell you that, and I can't tell you that you're a good person, and that you'll be okay. Because I don't know that for myself, let alone anyone else.

I have holes in my memory. Things I don't want to live with -- that I can't stand to think about -- go away. I cut them out with imprecise scissors, snipping away the tissue and removing the pieces that I can't bear to see. The arteries. The sinew. Connective things.

It all leaves behind a hole in the shape of a person. A shadow that thought she could be a person.

Some day, I'll talk about Shinji Ikari.

Hideaki Anno's birthday is May 22nd. Mine is May 18th.

He's described himself as something of a vegetarian off and on over the years. I would consider myself the same.

From what I understand of his world views, he's an agnostic. I would consider myself much the same.

He's old enough to be my father, born in Ube in 1960, under the shadow of smokestacks and industry. The city's skyline has ingrained itself in my vision of Anno as much as any other piece of trivia.

Anno is a bundle of contradictions. At times he comes across as a thoughtful craftsman dedicated to pushing the animation industry to its full potential. Others, he can come across as arrogant, off-putting, or dismissive. He can be funny or crass, and sometimes even sexist. He is carried around the halls of discourse as an author and auteur but he rejects these labels, talking up trusted collaborators and artists instead. The care that he has for his work and the ideas that fascinate him shines through his simultaneously awkward and bluntly charming public persona. So does his frustration with himself and the work he's produced, which he has been at times intensely open about. He very dearly loves tokusatsu, manga, and the popular culture of his youth. He is an otaku's otaku.

Listening to him talk has become a field of study for me the same way one would research the production of animation itself. I like to listen to him talk because, and I mean this with respect, he doesn't seem capable of giving a straight answer. Or, at least, not entirely consistent ones. You can't quote him with any real certainty on most things. Looking at interviews a month before or after a particular statement can yield very different answers depending on what period of his life we're focusing on and what we're talking about. Sometimes you get the impression that he might be lying by omission. Cleaning up the details. Fussing with the contours of his answers to either end the conversation or say what needs to be said at that moment.

You can see why someone like me would find someone like him so interesting.

But I don't know Hideaki Anno. Of course, I don't know him. I could never know him, no matter how fascinated I am by him. I feel like I can relate to the way he talks about his work and his struggles with it through the years. I respect him. I like him, through the layers of abstraction that it takes to say that you like the idea of an artist, even if he is the architect of something that has caused me so much strife.

After all, Anno created Shinji Ikari, a character meant to represent a well-documented, frequently discussed period of depression and professional failure.

If ugly, needy, self-loathing had a face, it would wear Shinji Ikari's.

What is it about images and cells and inscrutable membranes that makes these things feel so intimate?

In the months since I spoke to my brother about the things I didn't remember, Evangelion asserted itself into my life. Returning to the show and films feels like a compulsion. A ritual.

Alone at home during the day for work, I put on episodes to pass the time. It's comforting because I remember all the lines. If Melissa is away on the weekends and I'm home alone, I crawl back in bed and watch End of Evangelion. Any time spent alone in the car is an opportunity to listen to the show and film soundtracks.

I make a joke of it on social media by posting the Neon Genesis Evangelion opening theme, A Cruel Angel's Thesis, every Saturday morning. I start calling it The Saturday Morning Song. I have a need to turn the things that I do into jokes so other people can't use them against me. What do you think that says about me?

Driving around, I listen to every version I can find of Komm, süsser Tod in my car on repeat. It soothes me in a way that doesn't really make much sense. Listening to One Last Kiss by Hikaru Utada is something I have to do alone on drives because it makes me emotional. Every time I hear it, it feels the way going to a funeral feels. Funerals always make me feel like I've been split in two: the me sitting on the pew and the me lying in the casket. Connected by wires, veins, umbilical cords.

You always bury a little piece of yourself when someone dies, it seems. For better or worse, a part of you goes into the grave. The coffin lid closes that connection by severing the tether between you.

The song ends.

I start it over.

I go home and watch Evangelion: Death (True)² because I like to see the kids all practicing their instruments together. Shinji playing the cello always makes me happy.

Growing up in a house built by lies makes you a liar.

Love is conditional. Truth is conditional. Memory is conditional. You are weak because that's what people say you are. You are bright because that's what people say you are. You must stay at home and read books alone in your room because that's what your parents tell you to do.

Friends are obstacles. Family means everything. Anyone outside the family is a threat to the cohesion of the group. Your father is the only person who matters. He gets to have feelings. You get to be quiet. He screams and throws things and makes you feel like an idiot because you smiled too much or you laughed too loudly or you made the mistake of crying.

Your father is the only person who matters.

Everyone else must make him happy.

You don't get to leave the house. Not really, anyway. You're homeschooled because your parents told you that you're too anxious and depressed to go to real school. When you're old enough to read, your mother eventually leaves you to teach yourself. You have little brothers. They need tending to.

The few friends you do manage to make and keep, as fraught as those friendships are, you only have because your friends are brought to you. They are your window to the outside world when television and radio fails you. You have no social skills. You can't cope with new or strange things. You hurt yourself when you're overwhelmed. You make other people uncomfortable because you don't know how to behave. Your parents don't get you help. You have no relationships with anyone who isn't physically brought into the house. Your aunts, uncles, and cousins, all embroiled in various dysfunctional relationships of their own, live many hours away.

You only have one grandparent. Your maternal grandmother, Maxine. You have her in your life simply because she made the effort to write and visit when no one else did.

What little you have eventually falls away with time. Before you know it, you're a teenager. The friends who used to come to your door no longer have any use for you. They all have interests and hopes and dreams beyond you, because you've been told you shouldn't even try. You don't even think you can get a job or go to college. You resign yourself to a future of cleaning your parents' house so they'll allow you to keep living there, because you don't know how to be a person.

Nobody ever taught you to be a person.

They taught you to be quiet.

But you're fifteen, and you have the internet. You can go anywhere and talk to anyone. Your parents can't stop you. On message boards, you can lurk on other people's conversations and read about TV shows and movies you have no access to in your shabby little Fort Worth suburb. On the edge of corn fields and cattle ranches, where your only understanding of anime comes from censored episodes on Toonami. You can talk to people who wouldn’t know what’s wrong with you.

That's how you discover Neon Genesis Evangelion.

It happens by accident, reading through forum posts and Web 1.0 articles on this incredible, beautiful, life-changing show. Evangelion was so much more than anything you were watching, they said, they being strangers on message boards whose discussions you read through. The fans seemed older, more worldly. They talked about Kabbalist symbolism and Christian iconography, arguing passionately over Bible verses, philosophers, and the meaning of life itself.

This was a very different fandom than the kinds you were used to lurking around. At the time, you ran an Outlaw Star fan shrine and spent hours every day on Cowboy Bebop forums. To your small and fragile mind, this weight and importance meant Neon Genesis Evangelion must have been very special. You dedicate your time to understanding this thing you had never seen before, pouring through episode scripts, downloading hundreds of pages of meta written by forum moderators, and tracking down manga scanlations.

The show was impossible to find at first, as a teenager in a working-class family currently struggling to keep the lights on. You can't explain to your mother working twelve-hour days as a bartender that you needed $300 to buy VHS tapes of a cartoon off the internet. Instead, you settle for pirated episodes of the show and the original theatrical cut of Evangelion: Death and Rebirth, piecing together the series from low-quality VHS rips. Some were dubbed, had subtitles, or were Japanese-only. The inconsistent languages and low fidelity made it difficult to get a complete grasp of the story, but that made it feel all the more special.

Here was Evangelion, this beautiful puzzle that God made just for you to solve, with all its misshapen pieces and incomprehensible lore. It belonged to you in a way nothing else in your life did. These characters felt like they were made for you to love, to sit with in the dark and warm you through the screen.

Then you got to Episode 24: The Final Messenger, Kaworu's first and only appearance in the original show, and--

Well.

Let's stop there for now. There's something else I need to talk about first.

I lied before, when I talked about 3.0+1.0. If not a lie, I told a half-truth. I told you before that I have holes in my memory. I also told you before that I couldn't assure you that I was a good person.

It's true that I wept for the last hour of the film and was touched by the uplifting conclusion of Shinji Ikari's story. But it's equally true that I felt betrayed in a way that I couldn't quite put words to at first. I said Kaworu Nagisa is my favorite character and that's true, too, but--

But--

I was so upset that Shinji took Mari's hand and ran away with her.

I was so upset that Kaworu was left standing on the train platform, separated by a passing train that might as well be a continent between him and Shinji.

I was so angry that Kaworu left with Kaji. I was so angry that Kaworu was positioned behind Gendo's desk and that Kaji was his Fuyutsuki and Shinji

Shinji

Shinji

Kaworu was Gendo and Shinji was Yui and his love their love this love this love was the same destructive obsessive thing that burned a hole in the sky and turned the seas red and forced the horrific choice on Rei and Shinji and Shinji just

Shinji left with Mari

But why was I so upset about a story I didn't remember loving the way I did? Whose final final final conclusion I was afraid to see alone, as if it could reach through the screen and strangle the life from me?

Why was I so upset that Kaworu was left on the train platform?

Why was I so upset?

No one did this to me. No one hurt me.

Why did I feel so fucking hurt?

I don't have very many memories of my mother prior to my later teen and early adult years. She's still alive, of course, and she was present in my life. I just don't really have much to grasp onto.

The one thing I do remember was that I have always sat on the kitchen floor while she was cooking. My mother is a product of Missouri hill country. Most of her recipes came from two editions of the family church cookbooks, which had circulated in the community for decades. That meant everything could be made into a casserole if you tried hard enough.

I used to sit on the floor, my knees tucked against my chest. We would talk. Mostly I would talk at her, I think. I was a child with a head full of books and not much else. I had strong opinions on things I didn't understand. That remained true for much of my adulthood as I realized that I only interacted with people who came to my door. I learned the rest from my father's sermons on how terrible people were, how everyone was out to get him. How friends only slowed you down and got in the way.

It's sad to think now that I modeled so much behavior off of television because I didn't know what was expected in social situations. What to watch out for. What to graciously accept. When any attention feels like a bright light in the dark, people learn quickly that they can exploit that. Then what my father said became true.

The self-fulfilling prophecy of the unlovable and the unloved.

When I was ten, maybe eleven, I remember telling my mother that I didn't want to get married. I didn't want to see or touch a man. Love was a lie and a waste of time. The truth was that I hit puberty at nine-years-old and grown men never let me forget it. Breasts, a period, all of it. Men scared me. The mere idea of a penis, seen in the science books I read alone in my room, felt like a punishment I had to find a way to escape.

I only knew of sex from movies and the schoolyard talk my precious few friends brought into the house whenever I saw them. None of us knew anything. I would come to find out later that some of the children I knew were being abused at home. All of our information was rooted in fear and shame.

I remember my mother getting angry at me about that. That I didn't want to get married and have children. She may have been frustrated about something else and took it out on me. I don't know. I felt as if I had done something wrong and quietly left the kitchen.

If you asked me a year or two ago what my favorite anime was, I likely would have told you it's Neon Genesis Evangelion. If you asked me why, I likely would have told you that it's because it's my The Catcher In The Rye. I would have said that because it's easy.

J.D. Salinger's The Catcher In The Rye is a simple and generally useful shorthand in my eyes. It's a book that I read and many other people that I know read. That many people in American public schools read. It's a kind of coming of age experience that resonated with many people in a very particular time and place in their lives. They were teenagers and it probably made a lot of sense when they were the same age as Holden Caulfield. It talks about loneliness, trauma, loss, alienation, anger, and the phoniness of adults. The meaning, emotional logic, and relatability changes as we grow and mature into adulthood, moving further away from that moment in time. You either love it or hate it. There doesn't seem to be much room in between these poles.

If you asked me what Neon Genesis Evangelion meant to me now, I couldn't tell you, because I would say that I had grown beyond the need for it. Just like I had Holden Caulfield.

The answer is simple and easily digestible. For the purposes of passing conversation, Holden Caulfield is Shinji Ikari. On the English-speaking internet, it's okay if you hate Holden Caulfield the same way it's okay to hate Shinji Ikari. People feel comfortable hating him.

The reasons vary.

He's an ass. He's boring. He's homophobic. He's a sniveling twerp. He's a whiny, needy, embarrassing teenager. He's privileged. He's an incel. He's angry. He's entitled. He's a misogynist. He's a creep. He's a school shooter in training.

Holden is an unlikable character in a book that can be unpleasant to read. It doesn't help that Mark David Chapman was so inspired by his love of the book and Holden that it fueled him to shoot John Lennon in 1980. It doesn't help that John Hinckley, Jr. tried to shoot Ronald Reagan and cited both Chapman and Holden as inspiration in 1981. It doesn't help that Robert John Bardo was carrying The Catcher In The Rye on his person when he murdered Rebecca Schaeffer in 1989.

When he was arrested, Chapman was found with a copy of the book, the following note written inside:

To Holden Caulfield, From Holden Caulfield.

This is my statement.

And in the spirit of honesty, I didn't like The Catcher In The Rye when I first read it. I didn't even read it when I was Holden's age. I was too young at the time, maybe twelve or thirteen, and I hated Holden Caulfield. I thought he was a loser and a whiny jerk. It was a book with a reputation for being liked by stalkers, and that's all the thought I could spare for it.

When I read it in college for a young adult literature class, it made far more sense to me. I was old enough, now in my late 20s, to look back at Holden's experiences and understand his grief, frustration, fear, and trauma. Holden is a deeply troubled teenager struggling and failing to deal with the death of his brother, implied grooming or assault by a teacher, and the terror of joining an adult world that seems bent on destroying anything good or innocent that it touches.

I enjoyed the book on my second read because I liked the way it was written. I got something out of it because I felt like I understood where Holden was coming from this time. You don't have to like him. I don't particularly like him. You can think whatever you want of him. I can't help that some violent people have turned him into their personal avatars, no more than I can help that some people pretty famously missed the point of Fight Club or Breaking Bad.

And while I want to say I feel the same about Shinji Ikari...I don't. I never hated him. I never wanted to hate him. I don't find him easy to hate.

But I can't say that, because I'm supposed to hate him. Because you can't talk about Evangelion online without talking about everything else people want to say about Evangelion.

You have to talk about Hideaki Anno's depression.

You have to talk about best girls.

You have to talk about the fact that there were forum threads dedicated to how to torture and kill Anno after the final two episodes aired.

You have to talk about queer-baiting and bury your gays.

You have to talk about the Netflix translation.

You have to talk about how Anno is a megalomaniac who hates his fans.

You have to talk about End of Evangelion.

You have to talk about the scene, that scene, the scene that people throw in your face with a sneer when you say the name Shinji Ikari on the English-speaking internet in 2021. The scene where Shinji, at his absolute lowest point as a human being, pathetically masturbates at the sight of Asuka’s comatose body and acknowledges the depravity of his own actions in a fit of grief and despair. Because if you don't talk about that scene and protest its presence in the canon, you're a nasty little incel freak who views Shinji as your personal avatar.

Nevermind that a great deal of the film's surrounding sequences, and arguably this scene in particular, were intentionally positioned as responses to and critiques of otaku culture and the juvenile fantasies of fans within it, by artists from that world. Artists who, for reasons that change over time as recollections vary and opinions wane, wanted to in part comment on the state of audience expectations and engagement with fictional worlds through the membrane of their own fiction, their own avatars.

But get in the fucking robot, Shinji. Nothing can ever be uncomfortable. You can never sit with something ugly, even in a series that never shied away from ugliness. This is the event horizon of discourse. Shinji is an aspiring rapist and so are you. Don't question the memes or the YouTube videos. Men who recently discovered feminism on the internet know better than you do.

So, you just have to say it's your The Catcher In The Rye. A story for teenagers with their soft feelings and easily bruised skin, who are hurt by adults who were hurt by other adults. Generations of hurt, cycles of trauma, cells interlinking cells. You say it meant more to you as a teenager than it does now. It's easier that way.

You cut it out of your memories.

It's just easier that way.

And you never talk about Shinji Ikari.

When I was sixteen, I decided I wanted to write a book. It took the shape of what I thought a book was. At the time, I read horror books and science fiction, mostly. Warren Ellis comic books and William Gibson novels. I don't remember much about being sixteen. Or seventeen. Or eighteen. Those years were a dim blur like a badly developed Polaroid. I had been sick for a while, the kind of sick that cost me the enamel on my teeth. An inconvenient kind of sick because it cost time and money. It was the only time I remember my parents taking me to the doctor, and even then it was just my father's doctor.

I didn't get a doctor growing up. If something was wrong with me, I would just get better on my own. I vaguely remember going to the doctor when other people got hurt or sick, but not me. At the time, I had debilitating chest pains that left me in bed, squirming and crying. In a few years, I would develop a stomach problem that made me vomit at least once a week.

If it couldn't be treated with an herbal supplement, it didn't get treated.

That was just how it went.

What I do remember about being sixteen, besides being sick, was writing a book about living machines. Alien life forms that came to Earth, captured by humans for weaponization and exploitation. There was an apocalypse of some kind. Alien-human hybrids were used as techno-organic war machines and helmed by human pilots.

There were two main characters: a red-eyed boy named Ryu who was angry and unloved, abandoned by his parents, and a blue-eyed boy named Sasha who had softer edges and a servant's heart.

Theirs was a story about grace.

I never finished it, obviously.

When you talk about yourself in these terms, people expect there to be an inciting incident. A moment that you took up the shovel to bury your memories. There must be a singular event that caused you to dig a grave for yourself and a headful of things you choose to forget.

Looking up from the dirt, you see yourself standing over the pit. You are standing next to a boy in a Japanese middle school uniform. You can't bear to remember any of this. The shovel drops dirt on top of you until you don't anymore.

You don't get to choose what you keep or what you lose. You remember being a brazen child who tried to teach your dog how to read at six-years-old, and yet still ran scared from a cigarette burn in the carpet. You had it in your head that the Devil put the burn mark there when he opened a portal to Hell in your apartment. God knew all your secrets and sins, and so did the Devil.

You remember your father throwing shoes and screaming. You remember him yanking you into a car to scream at you. You remember him saying that you were his favorite when you were too young to talk but not after that. You remember him reading The Hobbit to you and you thinking that he loves you. You remember him saying that by the time you were a teenager, you were like an alien, irrational and unknowable.

You remember your mother reading James and the Giant Peach to you. You remember your mother staying up all night smoking cigarettes and drinking beer. You remember your mother doesn't wake up before eight, nine, ten o'clock in the morning. You remember climbing up onto the counter and getting Pop Tarts and cereal out of the cabinet for you and your brothers. You remember making chocolate milk and eating potato chips in the middle of the afternoon when your mother falls asleep.

You remember you aren't allowed to go to real school. You remember that everyone told you that you have good memories and that your parents always loved you. You remember being told that you had a good childhood because you had toys to play with.

You shovel more dirt into the hole.

Eventually, you run out of things to put in it.

So, there's a story that Kaworu Nagisa is based on Ikuhara Kunihiko, the director of Sailor Moon and Revolutionary Girl Utena, after a night he and Hideaki Anno spent drinking sake and talking in an open air bath.

It isn't a lie because the story is true, according to Kunihiko. The directors are friends and talk about these things in interviews, if asked. While Evangelion was still in preparatory stages, the men went on a company trip to an onsen with the rest of the Sailor Moon production team, of which Anno was a member. Anno directed the transformation sequences for Sailor Neptune and Sailor Uranus in Sailor Moon S and worked on an episode of Sailor Moon R. The numerous connections between Neon Genesis Evangelion and Sailor Moon are deep and well-documented if you know where to look.

The story goes that their conversation, this moment between two men in a bath, was committed to the script of Episode 24 in the bath scene between Kaworu and Shinji. That the two men drank long into the night after their cohorts went to bed. Reminiscing about their lonely youths, and Kunihiko telling Anno that he didn't have to try so hard.

That things would work out.

That he was worthy of love.

This did not happen. Both directors have said as much, from what I understand of the situation. They stayed up late drinking sake and talking openly about their lives. Intimate, but not romantic.

...But it sounds true, doesn't it? It sounds like something you would want to be true. It feels like it could be true, too, in that romantic way that we expect a piece of fiction to twitch and breathe with the lives of those who made it.

That desire to believe romantic stories about people we don't know brings me to the August 1996 June interview I've had open on my phone for the last year. The one I've read multiple English translations of, switching back and forth to get some clarity on what exactly is being said and how I'm intended to understand it.

Here are some parts that I find relevant:

Interviewer: Usually, Anno-san, you and one other person are credited with the screenplay, but what sort of a relationship do you two have?

Anno: I had him do the plot after we spoke together, and I fixed up what took the form of the script once more to get it ready for animation.

Well, at that point in time, we were writing the script to send out, and so you could also say that the stories, drama, characters, and so forth that we’d thought of during previous meetings were starting to lose consistency at the time that that script finished.

We have to fix those so that they line up, so. I’m unifying it, so it’s becoming uniform, though. I help with the drama parts and so forth.

Interviewer: Who worked on episode 24?

Anno: A person named Satsukawa (Akio)-san did that. Satsukawa-san is better at—this is bad to say, but—he’s right on the mark when it comes to homoeroticism. *laugh*

Interviewer: Did you stop Satsukawa-san when it looked like he was going to go berserk, Director Anno?

Anno: No, nothing like that. Satsukawa-san’s atmosphere remains in the script. Satsukawa-san’s original script had more of that sort of meaning and was June-like.

…

Interviewer: You said previously that that sort of June-like, or should I say the sort of production that goes beyond friendship, came out that way naturally, didn’t you?

Anno: As far as I know, it’s possible that I put in a few guys like that. Otherwise, I wonder whether it might be that I have parts of me like that, myself, things that are at about that degree.

Interviewer: That level is quite a thing. *laugh*

Anno: As expected, I was called odd by the staff. *laugh*

Make of that what you will.

It's strange to remember things that you forgot. To feel unmoored from yourself, a failed transmission between your brain and body. Cells breaking down. Connections breaking down.

I spent a lot of time thinking alone in my apartment over the last year, seated in my broken cockpit while a plague raged on beneath me. I remembered things in waves. I remembered the days I had lost. The way the forums looked on my screen, their colors, the size of the text. The way I lost hours scrolling through episode scripts to try to imagine the things I couldn't see for myself. The way my pirated version of Episode 24 included choppy pieces of Episode 23 and I thought they were the same episode for a long time. I had never known what a cello was or what it sounded like until the episode where I saw Shinji play for the first time.

The cello became my favorite instrument. It always makes me emotional when I pick one out of an orchestral arrangement, or see someone play in person. To me, the cello makes the fullest, deepest, most melancholic sound. Hearing it makes me think of hands, fingertips brushing as two people connect, then disconnect. The space between them grows as their bodies retreat, until that space becomes a continent.

Remembering these things feels like talking to God.

I sit in my broken cockpit and listen.

My girlfriend and I take a lot of walks together. It's better for us, in similar but different ways. Consistent, low-impact physical activity helps her minimize the pain associated with her multiple sclerosis, whereas walking helps me control the worst of my chronic pain and nerve damage. We make quite the pair, her with a brain eaten by lesions, me with a broken back and a left side that just goes numb from time to time.

During the height of the pandemic, going to parks and taking long walks was the safest way to get out of the house. We had both been furloughed from our jobs, me for two months and her for eight. The future was uncertain and we were living off unemployment benefits, at a time when we didn't know how the world was going to look and what kind of life we were going to have in it. Walking was a respite from that. Sometimes we walked with our dog, sometimes without, depending on his mood and how long we would be out. Either way, it was nice to just…disappear for a little while and be in nature. Sit in the grass. Read a book. Talk about writing.

It was on one of these long walks, while sitting at a picnic table hidden on a nature trail, that we both put voice to the reality that neither of us felt comfortable being called women. Womanhood felt like an ill-fitting suit, something we were expected to wear around at parties and discuss with strangers. The performance didn't make sense and, beyond biological similarities and shared social experiences, talking to cis women always felt like speaking a different language. We had each arrived at this conclusion in the past, at different times and through different events, but never really felt like there was anything that could be said or done with this information.

After all, neither my girlfriend or myself wanted to transition into another gender, socially or medically. We weren't trans men and we didn't want to be trans men. It always felt strange to act like we were something other than women, even if the label didn't fit. Being a woman didn't feel like a fight either of us wanted to have, or a title we desired defending. But during the height of the pandemic, sitting in our five hundred square-foot apartment with nothing but four walls and each other to stare at, we each arrived at the same conclusion.

We weren't women. We weren't men. We were something else.

And that was…okay.

I ended up posting about it online. It seemed like the right thing to do, as a writer and a private individual. Just a head's up that the context of me, this ongoing performance of Magen Cubed, had changed. Not radically or externally, or in any particularly interesting way, but it was still a change. I don't know if that was a mistake, in the long run. Some days it feels like all I did was open myself up to new, slightly different but no less impossible expectations from people who don't care about me.

Then again, what's new about that?

We want so badly for our stories to reflect us, just not the stuff we don't want to see. When we speak of identity and authenticity, we still want soft lighting and a filter to make the chipped teeth and scarred hands look gentler. Prettier. A manufactured reality, where none of us seem as bad as we fear we might be.

I don't have that luxury when it comes to stories about myself. I only have the stories I was told. There's the version of me presented by my family, and the one I lived inside of. I never knew which one was real.

When I was fifteen, my grandmother Maxine moved into our house so we could take care of her. I had always been close to my grandmother, my mother's mother. The only grandparent who ever spared me any kindness. I had a whole other set on my father's side who were excited about the novelty of a granddaughter. A family first after generations of boys. They quickly lost interest in me when their other son had a daughter, too, and only visited once or twice. I never spoke to them except for strained holiday calls, asking me to call them the pet names they made up for me. Telling me to tell them I loved them. My mother's father didn't bother to raise his own children. I was told he couldn't remember my name when I was a baby, so he used to just call me Magnum PI after the TV show.

My parents lived with him at the time, as I feel compelled to note.

I was never worth remembering, it seems.

My grandmother used to sit and read books with me. It didn't matter what kind. History books, science books. Maxine always wanted to go to college but life in a one-road town didn't allow for that. She was so thrilled that I wanted to read books and write novels and comics. I sent her handwritten stories on notebook paper in the mail and she would send me excited pages of feedback in return. Once I had a word processor on the family computer, I could print out my stories and mail them off. I could make novels now, with clipart for the artwork. I felt very grown up in that.

Now my grandmother was on medication that changed her personality, according to the doctors. It was supposed to treat the initial symptoms of dementia, but I can't tell you where the condition began and the medication ended. Maxine became a hostile and aggressive shell of a person. She used to forget things, but not like this. Now she would sneer over perceived slights, even if no one was talking to or about her. I had to keep an eye on her to keep her from cooking with dog food or wielding a kitchen knife like a pen. Things didn't make sense anymore.

But it was on me to try to figure out. My father lost his airline job after 9/11 and spiraled into a deep depression and later illness. My mother had to wait tables and tend bar to pay the mortgage. We nearly lost the house before my parents filed for bankruptcy for the second time since I was born. My brothers and I were no longer being homeschooled because no one was around. I tried to keep my brothers, eleven and thirteen at the time, on track with their school work. Eventually they gave up and just played video games all day instead. My parents said they could just get their GEDs one day and it would all work out.

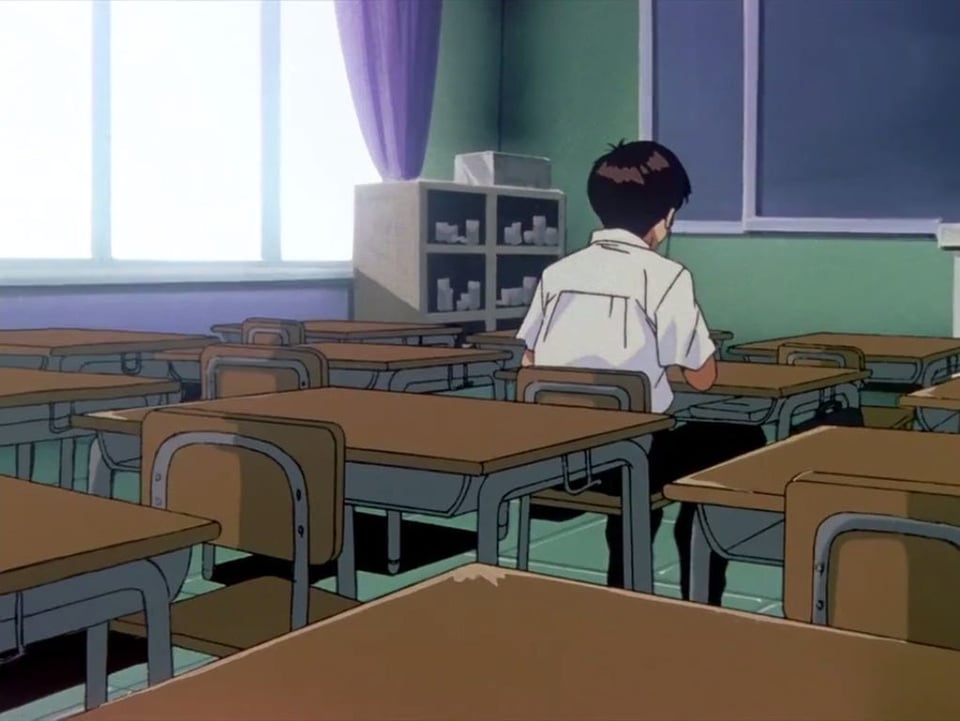

Meanwhile, I had Neon Genesis Evangelion.

I had floppy disks full of episode scripts, production art, manga scanlations, doujinshi, and message board lore dumps. A folder on the hard drive of fuzzy pirated episodes with questionable translations. It was my warm, bright little secret. Something I got to keep to myself, a calming blue light on a screen, until I was ready to share it with someone else.

The story I told myself later was that my brother Ian showed Evangelion to me first. It made more sense if he did. I was just the hanger-on who liked what other people liked. What began as me sharing something I deeply loved with my brother became another thing taken from me because, in my mind, I was too weak and stupid to have it for myself.

And Ian remembered what I couldn't, even after all those years.

But that's only part of why I forgot.

The thing about Shinji Ikari is….I get why people hate him. It's easy to hate him because he's built for it. Shinji tells you as much. He's indecisive to the point of frustration, especially for those of us in the audience who have been trained by Joseph Campbell and the hero's journey. He's subservient to the will of others in a misguided bid to earn their affection. It doesn't often occur to him that others are suffering just as much as he is, lost in his own haze of self-loathing and fear.

He whines.

Cries.

Runs away.

Shinji thinks he knows what love is because he thinks he knows what a man is supposed to do. Puberty is a nightmare of frustration and shame. He wants things he can't have, and I don't think he knows if he truly wants. Did any of us know what we wanted when we were fourteen, and saw another child in gym shorts or a bathing suit? When we slept next to a friend on the floor of our rooms and thought we knew what adults did?

Reading Stephen King's IT at three o'clock in the morning and talking and feeling like grown-ups until it becomes clear that you're still children. Wasn't it a little sad in the moment? A little needy, a little desperate? Didn't it make you feel like a loser? Didn't it make you angry, at yourself or someone else?

Shinji wants to be loved so badly, but being vulnerable enough to be loved, crossing that distance between himself and others, sends him collapsing back into despair. It only reaffirms his fear that he's beyond loving. Beyond saving. That he really is pathetic, a dreadful little worm of a person, and he doesn't deserve to live.

And I guess I just want to know that, if that's true -- if he is a dreadful little worm, an incel, an aspiring rapist, a school shooter in training -- what do you want to come out of that? Should the series have ended with Shinji in prison? In a mental institution? Should he have been killed? Should he have been made into a moral lesson against being a traumatized, self-loathing teenager? Should we punish him so nobody is ever needy or embarrassing in front of us again?

So we, ourselves, are never inconveniently traumatized?

But…that's not really why I can't talk about Shinji Ikari.

At least, not yet.

At some point, the remembering becomes violence.

Night brings terror. I don't sleep, trapped by wakefulness, unable to hold the remembering back any longer. The ceiling offers only silence. My chest aches the way it did when I was sick as a teenager. I don't remember getting out of bed on these nights, but I remember ending up on the floor and looking over the side of the bed at the clock. The hours drip by from night to morning. I want to crawl across the floor and scream.

This is what traumatic flashbacks are like, I'm later told.

It's like coughing yourself up. A birth through violent expulsion. I feel as my own fingers climb my throat to leave my mouth, pulling the arms up behind them. The me that isn't me claws its way out as I expel it. Born in black bile, this me knows everything I don't.

My doppelganger.

The one who never had a chance in that house.

I remember…everything. The knowledge feels like death.

This has nothing to do with Evangelion. Evangelion just reminded me of what was always there. But these things don't belong in an essay like this. You don't get to be privy to everything I kept in my grave.

Somehow, I will learn to put all these pieces back together. The me that isn't me who bears these marks on her, and the me who cut them out. A soul bifurcated. Two stories made one again.

I don't know how to do that yet.

There's nothing else I can do.

Sometime in August of 2021, I'm sitting on a Slack call for the morning team meeting. Me and three of my coworkers commandeer the meeting to talk about 3.0+1.0. One of my coworkers, a web developer, says she was a huge fan of Evangelion in college. When she tried to go back and watch it now, it just didn't make sense anymore.

She was my age, thirty-five, with a husband and a baby.

I say maybe that's a good thing, to grow past stories like that. It means she's probably in a good place.

Shinji might be her Holden Caulfield, but he isn't mine.

And what does it say about me that I'm not done with Shinji Ikari? What does it say that I'm, at time of writing, a thirty-six-year-old adult who relates to the struggles of a fourteen-year-old boy? That I will only continue to age and change and Shinji will still stay the same, trapped in cells of animation? After all, I have a steady day-job in a lucrative field, with benefits and a decent salary. I'm in a long-term relationship with someone I've loved for over a decade. I've written and published several books and short stories. I've had bylines at award-winning media outlets.

For all intents and purposes, and especially on paper, I look like I have my life together. I look well-adjusted. Normal. Happy.

So why do I still need someone like Shinji Ikari?

Why haven't I let him go, like Holden Caulfield before him, to escape into the rye?

My coworkers now know to send me Evangelion .gifs in the work Slack channel. I guess that's kind of funny.

In previous versions of the series outline end episode schedule, Kaworu Nagisa is a beautiful and popular new transfer student who takes an interest in the shy Shinji Ikari. He is the perfect vision of masculinity, as Anno has remarked in interviews. The inverse of Shinji's inherent femininity.

"There’s no feminine sense whatsoever, right? Because it’s Shinji and another Shinji. Since it’s an ideal of Shinji’s that’s appearing, it can’t be a girl."

The girls at school love Kaworu while the boys are immediately suspicious. Kaworu and Shinji share an umbrella in the rain and they swim together naked in the river after school one day.

This does not last.

In one of the initial drafts of Episode 24: The Final Messenger, Kaworu is a suicide survivor with stripes on his wrists. He and Shinji bond over music, Shinji's cello and Kaworu's piano. And--

Well--

INT. NERV HQ, RESIDENTIAL AREA - SHINJI'S ROOM

Shinji realizes he's lying on his bed.

Kaworu is looking down at him.

KAWORU: You awake?

SHINJI: ……

KAWORU: You passed out. You really scared me when you collapsed.

SHINJI: Sorry…… for being such a bother.

KAWORU: You must be tired. I'm sure. So much has happened.

SHINJI: Yeah. A lot has happened……

Kaworu notices the cello in the corner of the room.

KAWORU: Is that yours?

SHINJI: Yeah.

KAWORU: It's a nice cello.

SHINJI: It was my mother's.

KAWORU: Oh, I know. We should play together. You on cello, me on piano. I'm sure it'll calm you down. It must be suffocating being trapped underground, just doing Eva tests all day.

SHINJI: But, I don't think my cello playing is as good as your piano. I'm embarrassed.

KAWORU: It'll just be for fun. Plus, what do we have to be embarrassed about at this point?

Shinji remembers his disgraceful behavior, and his pale face turns bright red again.

KAWORU: Is there a piano somewhere around here?

SHINJI: I think there should be one in the lounge.

KAWORU: I have a startup test with Unit 02 tomorrow. Let's go tomorrow after that. Promise?

SHINJI: Okay.

KAWORU: Well, I should be going.

SHINJI: Good night.

KAWORU: Good night––

Kaworu's face slides toward Shinji's.

Kaworu gives Shinji a kiss.

Shinji doesn't refuse him, he notices how naturally he accepts it.

Feeling strangely calm, he looks up at the ceiling light.

All of this falls away in the drafting process, while the kiss is inevitably cut from the final draft of the episode.

From what I can tell from interviews and production timelines, the relationship between Kaworu and Shinji was always intended to be a love story. In some context, to some degree, be it a school romance plotline from a previous vision of the show or an intimate moment between two boys in a bath. Whether Kaworu says the words "I love you" in that moment or not.

Fiction is a fickle membrane. It's a reflection of a reflection, where you catch yourself when the light is just right. We can't ever really know the heart of another person, their will, and what compels them to tell the stories that they tell. What moves them to make these things and put them into the world the way that they chose to, in a commercial project with investors and advertisers and producers who all have their way.

But sometimes what someone else fashioned with their hands and their heart's wish, inscrutable though it may be, reaches you. Sometimes what they make carries something of them inside of it, and it speaks to you. Sometimes it’s the quiet intimacy of two boys in a bath, speaking frankly about their feelings. Sometimes that's enough.

It took me a year to write this essay, the one you're reading now on a screen. I started writing it in 2021 after I watched 3.0+1.0. It became another essay. I kept writing this one because the story didn't end. There was no stopping point or polite ending that I could find as I wrote. Every time I thought I was finished, something changed. The writing kept taking on new shapes and dimensions, the way living organisms do.

I am the story.

This essay is me.

Unraveled and unmade.

This is not a story about a person inside a machine because Evas are not machines. They are people. They are memories. They are shells that house souls inside armor. And I don't have armor. I just had a house. My memory kept changing over the last year, like the house expanding into new rooms. Staircases sprang up from the dirt like discs of a spine, spiraling upward to the skull of the attic. Rooms grew out of the main corridor in tumors. Each new space became a place for terrible things to live and breathe.

I found myself in each room, the bile-born clone who held all the scars I couldn't. My doppelganger.

Rei Ayanami should have been my favorite character, right? It would have made more sense. It would make everyone feel more comfortable about the stories I have to tell.

The reason I couldn't finish this essay sooner is that, like the house, I was still growing. Still changing. Still remembering the things I couldn't. It took me a year of reciting lines from a twenty-six-year-old show and listening to songs that made me feel like dying and staring into the silence of my bedroom ceiling to accept that I am not the person I thought I was.

I am someone -- something -- else.

I raised myself from nothing, like this cancerous house.

I am who made me what I am, because I was left to do the work alone.

I am no longer a liar because I know the truth.

And...that's why I think it's time to tell the truth about Kaworu Nagisa, my favorite character. And to do that, I have to finally talk about Shinji Ikari.

We want to see ourselves in beautiful things, but we most often see ourselves in cruel places.

When I was a child and later a teenager, I knew that to be a queer person was a bad a thing. Being a girl was a sin in and of itself. My body had betrayed me by going through puberty too young and being an irrational thing my father didn't want. But to be a girl who doesn't feel like a girl,

To be a not-girl who doesn't want to kiss boys,

To feel physical terror at the thought of having to kiss a boy,

To feel that you were made broken in every way,

It's a cruel and lonely life, because there's no one else like you. There are no stories for you. The closest thing I ever had to a story about me was Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs, a man who wasn't a man because she was a woman. A malformed thing who butchered "real" women for their skins to make a suit for herself. The next best thing was Tom Ripley in The Talented Mr. Ripley, whose desire to at once love and be and possess Dickie Greenleaf drives him to murder Dickie and assume his identity. The next best thing after that was Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, where Jim Williams kills his gay lover Billy Hansen in self-defense after a violent fight. The ensuing murder trial tries to prove or deny that Billy had his murder coming.

At least the latter film featured The Lady Chablis, who was the first trans woman I ever saw on screen. She was probably the only trans person I ever saw as a child, until I was old enough to move through the world on my own.

Every story I ever saw myself in was a spectacle of violence and tragedy. I almost never saw queer women in fiction. On the rare occasion a lesbian made it to a screen, she was in a police procedural, living a joyless, loveless life as a footnote in someone else's case. If she was lucky, she made it to the end of the episode in her drab little apartment, her chest unshot, neck unstrangled, heart unstabbed. If she wasn't, she was just collateral damage.

And if she was bisexual, she was actually the murderer, of course.

Of course.

(The elephant in the room is Grencia Eckener from Cowboy Bebop, who has been wrestled with, debated about, written about, recontextualized, and reclaimed as a trans character. However, their transness, their breasts, are the result of forced medical experimentation. This transness is something that happens to them, enacted upon them by others. Their love for and implied affair with Vicious may be queer, but while I've always loved Gren a great deal, it's…a complicated affection.)

So you have to understand that when I was fifteen, I had never seen anything like Neon Genesis Evangelion before. The quiet sensuality between characters in lingering looks. Brushing fingers. Touching bodies. Moments of inexplicable closeness. Innuendo. The adult characters all had tangled pasts and flirtatious postures, having affairs both real on the screen and imagined in my mind. The boundaries between boy and girl were flexible, and intimacy didn't have to be sexual. Feelings didn't have to be strictly heterosexual. They could be nameless, the way feelings often are nameless. They could be messy and uncomfortable.

Shinji Ikari existed in the middle of this nebulous world, a little boy-god seated on a throne made of these complex connections, the wires and cables that run between men and women. Lilith and the Evas and the women in his life on one side, Adam and men and all the Angels on the other. God above them all, an elusive, silent creator, and Shinji the one given the power to accept or reject Human Instrumentality.

Sometimes the way Shinji's facial characteristics are animated give him the harsh severity of his father Gendo; others, he's given the softness of his mother Yui and her clone Rei in his eyes and mouth. He isn't very good at being the boy we want him to be, who wields the unlimited power of a mech but is outwardly gentle, timid, and demure. He excels at domesticity. He gets beaten up easily. He cries frequently. He tries to take care of others even when he doesn't know where he sits with them or understands that they're hurting, too.

Shinji struggles and almost always fails to perform traditional masculinity in any satisfactory way throughout the series, as he's forced into adulthood by the horrors of combat. When he flies into rages inside the cockpit, it's to tearfully defy his father and protect others from harm rather than kill on command. To defy God and the idea of violent, grasping manhood. His shared romantic feelings for Asuka are strained by trauma and the turbulence of puberty; the Freudian connection to Rei becomes all the more fraught as they try to care for each other. The masculinity he fights against is both at turns affirming and toxic, something lauded and something self-harming. He must constantly negotiate this tight-rope walk with the guidance of adults who are just as damaged as he is, and often lead him rudderless and alone.

Within the text of the show, the answer for Shinji isn't to butch up. It seems natural that it would be, but doing so only punishes Shinji further.

The answer posited by the text is for Shinji to find a way to love himself, and others. To be vulnerable and reach out to establish new connections when the old ones break down. These feminine attributes I can't relate to in my own skin are what will keep him alive and whole.

It's...an admittedly limited world view to talk about today, this dichotomy between genders. Written in the 1990s to explore the human condition through frameworks we squabble about on the internet (Freud, Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Heidegger, and Jung). Written by people who live in a vastly different social context than I do and are old enough to be my parents. But it's between this binary that I find Shinji Ikari to be so very much like myself. A boy who isn't quite a boy, at a time when I lacked the language to explain what being inside my body felt like.

A boy who isn't a quite boy who isn't loved by his father.

A boy who isn't quite a boy who doesn't want to exist.

A boy who isn't quite a boy whose developing sexuality is confusing and scary and violent.

You, the you that is on the other side of the screen, cannot understand how deeply I loved Shinji Ikari. You cannot know the depth of feeling, the profound ripple of understanding that came over me at seeing someone so much like myself on a screen.

You cannot grasp how much I truly loved Shinji Ikari, in my heart and blood and bones.

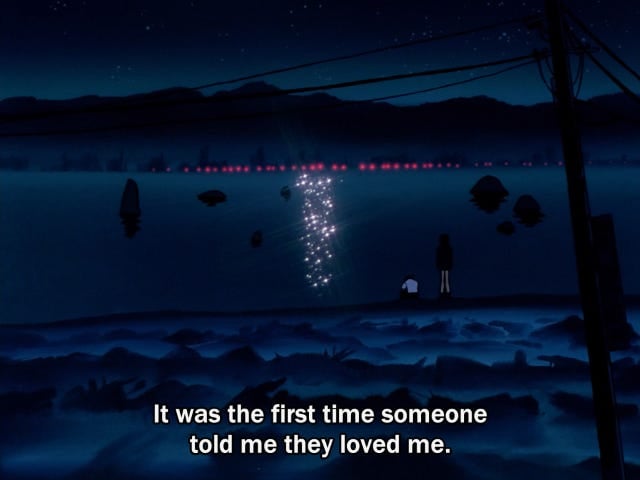

So, when I got to Episode 24: The Final Messenger, I was enrapt. Kaworu Nagisa, this perfect boy, this warm and confident masculine presence, embraces Shinji with open affection. Kaworu wants to know Shinji. He wants to be his friend. He believes Shinji is worthy of love and care at a time when Shinji is alone. The Rei that Shinji's bonded with has been replaced with a vacant clone. Asuka is catatonic in her trauma and grief. Shinji's afraid to go home to his guardian, Misato.

And Kaworu loves Shinji.

I'm a fifteen-year-old American. I don't know anything about BL storytelling conventions or character archetypes. I don't understand that Kaworu and Shinji draw on established tropes, and they themselves go on to further codify these tropes in stories that came after Evangelion. Nor do I get just how much Kaworu and Shinji draw from Ryo and Akira of Go Nagai's Devilman, their own tragedy woven into the thematic DNA of Evangelion. I just see two kids my age who are in love for the first time in my life.

Nobody is there to beat them.

Nobody is there to hurt them.

Nobody is there to tell them this is wrong.

Kaworu was born to meet Shinji. They touch hands in the bath. They sleep together in Kaworu's room. Shinji blushes whenever their bodies touch. This is love, in the fast and reckless way that young people fall in love, and it fills a well inside of me that I didn't realize was there.

I watch Episode 24 hundreds of times, until I memorize every word in the script. This is what Evangelion is to me: twenty-two minutes of possibilities. Kaworu isn't my favorite character; he's the promise that better things are possible.

In the end, there is no way for them to escape their circumstances. Kaworu, a half-human clone of Adam and a puppet in SEELE’s plans to end the world, allows Shinji to kill him so that humanity can live on. Shinji is the human that earns Kaworu's compassion as the 17th Angel, a human soul so delicate and boundless in its capacity for love that Shinji saves us all.

And then Kaworu dies.

And Shinji falls apart.

Human Instrumentality still happens despite Kaworu’s sacrifice.

Shinji still has to choose between blissful non-existence or the pain of living and loving others.

In End of Evangelion, Kaworu's smiling face is the one Shinji ends the world for. Kaworu, the Angel who died by Shinji's hand before Instrumentality, remains unreborn as Shinji awakes on the red shores of a ruined world with Asuka instead.

And it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. It was what I knew to be true. No matter how many times Evangelion ended, they would always love each other.

But I can't say anything about that, can I?

So, I just say that Kaworu is my favorite character, and one day, I show my brother this show I'd been watching. And one day, I forget because it's easier than remembering.

If you draw a direct line from Shinji Ikari to my entire body of creative work, you will pierce the heart of every character who was ever the most like me.

If you draw a line from Kaworu Nagisa, you will see that every love interest I've ever written has been the warm, loving center of a fearful, timid, and self-loathing character's world.

One who is worthy of grace, and one who bestows that grace upon them.

If not for Shinji Ikari, Dorian Villeneuve -- my most well-known character, from the series I'm most well-known for -- would not exist. Dorian who is the most like myself, non-binary with a small dog who keeps him grounded. Dorian who was abandoned by his family and thinks of himself as unworthy of love. Who runs away from the love he desperately, pathetically longs for because it's safer than being vulnerable to someone else. Without Shinji, nothing I’ve ever written will ever have existed. I love Shinji Ikari so much it hurts to talk about, and so I put those feelings into words.

His is the first queer love story I ever saw, reimagined and reenacted forever and ever. Disassembled and reassembled in new ways, new genres, new modes of being. Fruit forever born from the same tree. Cells interlinking cells in a membrane between myself and the reader on the other side of the screen.

I can't say for sure what was in the hearts of the people who made Neon Genesis Evangelion, but I know the mark they left on mine.

We want our stories to be neat and tidy. We want the people on our screens to tell us what we want to hear. As a woman-shaped person who doesn't feel like a woman, you still expect me to find empowerment and self-actualization in the stories you approve of. You want me to relate to the characters you relate to so that you can relate to me.

You want my queerness, my gender, my trauma, to unfold in a pleasing way.

You want me to tell you how I had my awakening watching Sailor Moon or Revolutionary Girl Utena. That I had an acceptable girlhood relating to positive characters. You might have accepted me more easily if I wrote fifteen thousand words about how Asuka Langley Soryu or Rei Ayanami helped me overcome obstacles and get better. About how Asuka's rage and reconciliation with her mother empowered me. About how Rei's rebellion against Gendo and her desire to be her own individual strengthened me.

My despair and rage is acceptable as long as it's still feminine, after all.

But I chose Shinji Ikari because Shinji Ikari is me. Shinji Ikari is you. Shinji Ikari is all the things we hate about ourselves, our doubts and insecurities and weaknesses. He's everything we hate and try to hide, because if we stared too closely into the mirror we would loathe what we see. Shinji is a frail boy who isn't very good at being a boy, with a dead mother and a cruel father and a soft heart that breaks like glass when touched.

And I love Shinji just as much now at thirty-six as I did at fifteen because…I didn't get better. I didn't watch Neon Genesis Evangelion and come away whole. End of Evangelion didn't repair the things that are broken inside me. I didn't even watch the Rebuild series, with all its hope and resolution, and feel complete.

I am a process. I am incomplete. Every day is a struggle to love myself, to forgive myself. To believe I deserve to be here. But I choose that struggle.

Evangelion reminds me that I'm not alone.

And Shinji reminds me that beautiful things are possible when you try.

The thing about stories is that they never really end.

Evangelion did, until it didn't. And then it didn't. When it was finally over, for the third and final time, I found myself with a broken heart and a head full of forgotten things. I had only lies to show for myself, and memories I had cut myself out of.

It was safer to never remember that time in my life, and the way that I felt. The way that Evangelion made me feel. It was safer to say that I was just angry that my favorite character didn't get the boy he liked in the end, but I see now--

After a year of writing and researching and watching and thinking about this thing that I held so precious to me--

That it hurt because it was finally over.

My first perfect vision of queer love was a fragile thing. The love of two teenagers, quietly burning holes into their hearts until they had the words to say that it was too imperfect to live. Kaworu had never lived a life beyond Shinji and his slavish devotion to making Shinji happy. Shinji had lost Kaworu over and over, still a wounded child struggling to find his way in the world and to stand on his own two feet.